Tuesday, January 2, 2024

Surviving Pearl Harbor: A story of three Indiana brothers who beat the odds with Courage, Resiliency, and an unrivaled Sibling Bond

(All historic images are courtesy photos given by Ivan's family and current photos are taken by Salon Osborne.)

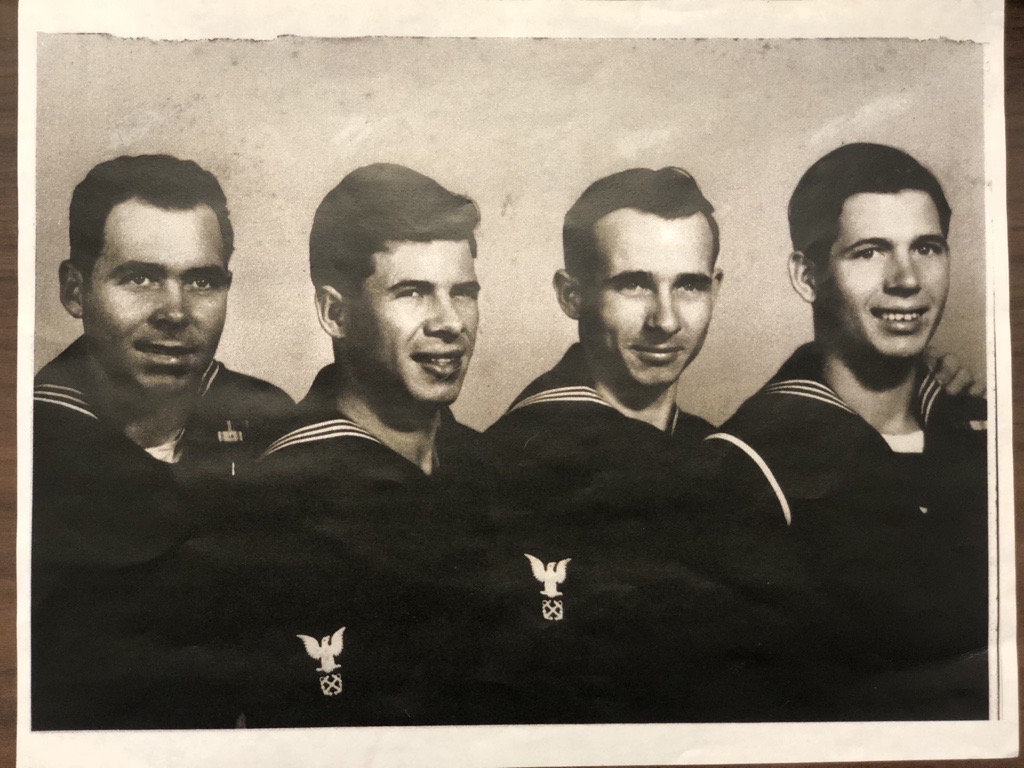

On Dec. 19, 1940, four brothers made their way from Taswell, Ind., located in Crawford County in Southern Indiana, to Louisville, Ky., to enlist in the U.S. Navy. The threat of the United States engaging in World War II was imminent. Brothers Ivan, Edward, Melvin, and Maurice Atkins wanted to “see the world,” and they believed that the best way to do it was aboard a ship.

Ivan, Edward, and Maurice were accepted into the U.S. Navy, but the youngest brother, Melvin, was only sixteen at the time. Melvin was permitted to serve with the Merchant Marines for one year, and if he still wished to join the Navy after a deployment crossing the Atlantic to deliver fuel to the Allies, the Navy would welcome him. If not, he would be granted an Honorable Discharge from the Merchant Marines.

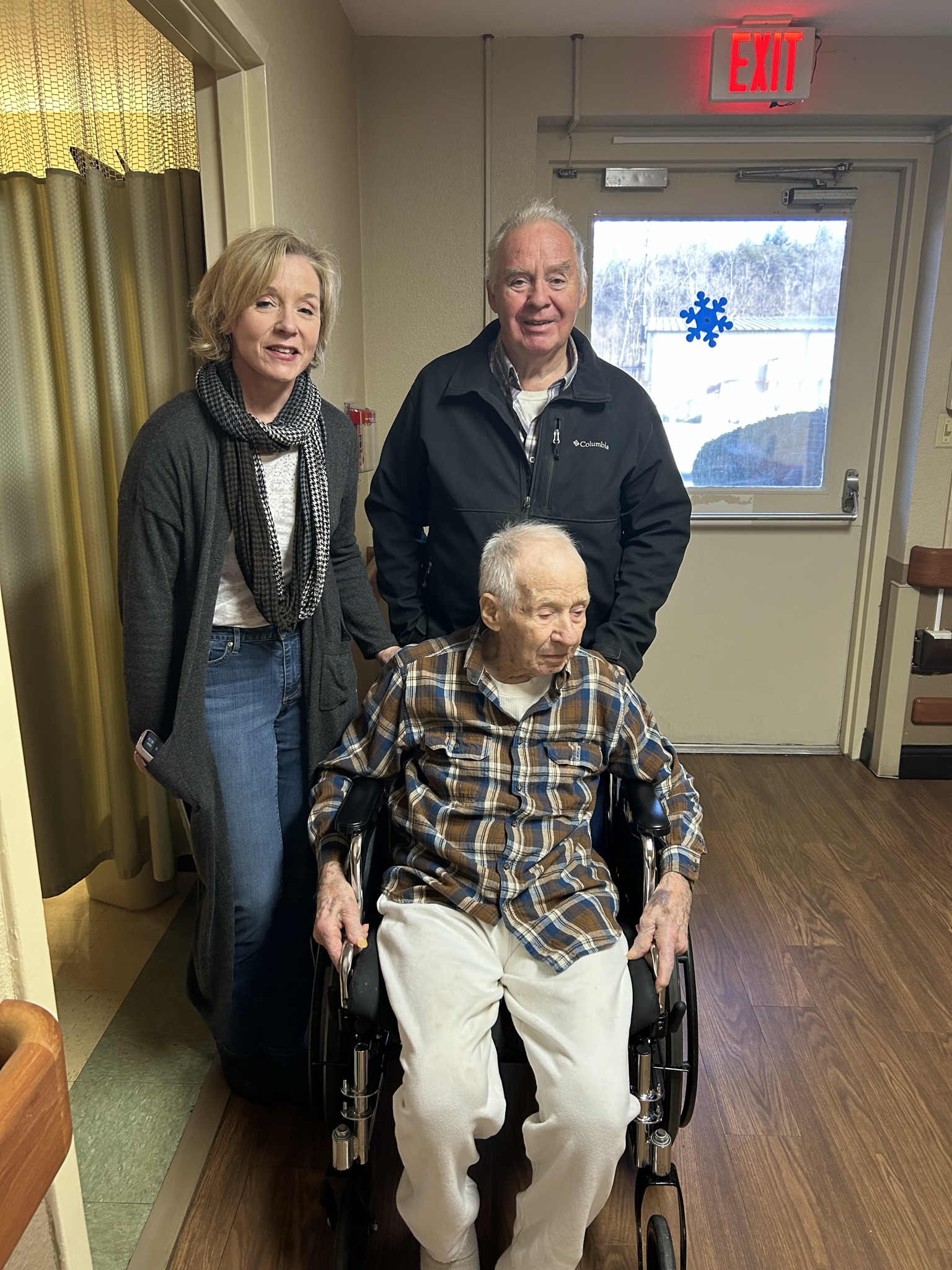

“Traveling and seeing the world seemed an exotic expedition to my dad,” states Ivan Atkins’s son, Alfred. Ivan Atkins recently celebrated his 101st birthday and is the last surviving brother of the four who enlisted to serve our country during WWII.

Ivan Atkins was born on Nov. 15, 1922, and is one of eight children born to Esther Dearborn Atkins and Wilson Atkins of Taswell. One hundred years ago, the family farm was a classic story of having a few cows, chickens, and ducks and growing organic produce before it became a trend. The Atkins family farm was known for selling watermelons within the county. The farm also produced sorghum.

One year later, with Melvin off to serve the war effort in a different military branch, the other three Atkins brothers were all assigned to the USS West Virginia. Their ship was part of the Pacific fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor.

On the morning of Dec. 7, 1941, Ivan, Edward, and Maurice were with the rest of the crew on the main deck for a full dress inspection. The USS West Virginia is a Battleship, BB Class, and was positioned fourth out from the docks, with the most exposure to open water. During dress inspection, the USS West Virginia was hit by four torpedoes. The captain ordered everyone to their battle stations, but many never made it to their posts. Another order issued by the captain was to open up ports on the other side of the ship so it would sink evenly in shallow water versus capsizing. This strategy saved hundreds of lives.

Scrambling to his post, Ivan could not make it to his gun down on the 4th deck below. Above the torpedoes’ damage, Ivan could climb back up to the main deck once the captain commanded the sailors to “abandon ship.”

“My dad shared that he could not see anything below the main deck and struggled to find his way back up. He saw a gleam of light above him and was able to climb up a maintenance ladder near a gun to reach the top deck. He could jump off once he reached the railing,” shares Alfred of his father’s experience.

Fortunately, Ivan evacuated early, as hundreds of men burned to death from burning oil on the surface of the water as the USS West Virginia sank.

Ivan, and eventually Maurice, swam to safety through an oil spill that had not yet been set ablaze.

“To be in a lucid state of mind and to make the correct calls when needed most, like the opening of port holes on the other side of the ship, saved lives,” shared Tonette Ramion, Alfred’s daughter and Ivan’s granddaughter. “We are grateful to the ship’s captain for implementing the right battle strategy at the right time!”

All three brothers successfully abandoned ship, but amidst the chaos of the attack, none of them knew if their siblings survived until the next day.

Edward had decided not to jump into the water, instead opting to walk across a gangplank to an adjacent ship. Once he stepped foot on that boat, he belonged to that captain. Edward’s newly adopted ship was on fire, and its captain refused to issue the order to abandon it. This resulted in the sailors fighting fires most of the day until the command was finally given to abandon the vessel.

Edward had jumped into the water and was swimming through a relatively shallow area when a Japanese bomb dropped ten feet in front of him, but it was a dud. He kept swimming. Edward Atkins is listed in the history books as “the last confirmed survivor of Pearl Harbor” due to the muddled clerical mess of changing ships during the attack.

With thousands of misplaced sailors, reassignments were necessary. Initially, Ivan and Edward, who would spend the entire war together, were assigned to the USS Turkey, a minesweeping ship but was initially utilized at Pearl Harbor as essentially a wrecker, transporting damaged ships to various docks for repair. Maurice was assigned to a different ship for the rest of the war. Ivan and Edward were later transferred to the USS San Jacinto, an aircraft carrier with an interesting history.

The USS San Jacinto was one of the most actively engaged warships of the North Pacific Fleet and one of the highest priority targets for the Japanese. A pilot assigned to the ship, considered the youngest Navy pilot in history at that time, was future President George H. W. Bush. Ivan served as a gunner on the USS San Jacinto and had an eye for spotting enemy planes, specifically kamikaze planes, on the horizon. A tragic part of Ivan’s experience was losing his gunmate six times during his deployment.

One recollection involved successfully neutering a kamikaze plane, with the cockpit landing on the deck without its wings. Ivan and a few others came to the rescue of the Japanese pilot, only to discover there was no way to extract the pilot from his seat.

Ivan’s muster papers show an honorable discharge date of Nov. 27, 1946. Ivan joined the Navy at age 18 and married his childhood sweetheart, Dorothy Mathers, before enlisting. During his service, he earned eight American Defense Stars and two stars for the Philippine Liberation.

“One of the most traumatic stories my dad shared with me was when he was ordered to close a hatch on the ship due to torpedo damage below, and there were still fellow sailors trapped underneath — he had to close the lid on some of his bunk buddies,” said Alfred, emotionally. “My dad saw so much action. He described it as ‘four years of blood and guts.'”

Upon return at the age of 24, Ivan placed his medals inside a cigar box and buried them in the woods, telling his wife, “No man should ever be recognized for killing others.” There was no access to post-war therapy then, and Ivan suffered from profound PTSD. He had been raised in the church and felt he had committed sins by killing people.

“My dad had a 5th grade education in a sheep shed. Literally, he had to walk to school one mile away through a field with a bull in it, which he had to strategically evade, and his school was inside a livestock shed,” states Alfred.

Ivan saved nearly all of his pay from the Navy and combined with his mother’s earnings from working in an airplane factory, they bought a 160-acre dairy farm for $1,700 in 1946. Ivan’s PTSD interfered with a successful run as a farmer, and he worked in woodworking factories in DuBois County.

“My dad had eight children and somehow took care of us and my mom. He was a small man, both physically and financially; he comes from the poorest county in the state and has survived to 101 and is still going,” shares Alfred. “Recovering from that war was a giant step. We all battle our own way through life – and my dad did it without any [mental health] support. Gives us all hope. I have seen a lot of people going through a tremendous amount of stress, but they keep on going and don’t give up.”

“My grandfather had a strong faith, which played a large role in his life. There’s no getting over stuff like that; you have to replace it with something else, and his faith replaced the trauma with love and joy,” shares Tonette sympathetically. “Back then, you didn’t sit around and talk about your anxiety. You pulled yourself up by your bootstraps and did what you were supposed to do. My grandfather was killing Japanese kamikazes at age 19. I cannot imagine the impact that had on him or anyone else. The historical part is amazing – what he went through — I cannot imagine going through that at such a fragile age.”

All four brothers survived the war. Maurice and Edward both lived to 79 years old. The youngest brother, Melvin, who did opt for that Honorable Discharge after serving with the Merchant Marines, died at 93. Ivan, still going at 101, is among the last of the Greatest Generation.