Location: 420 N. Senate Ave., at the southwest corner of Michigan St. and Senate Ave., Indianapolis (Marion County) 46204

Installed 2016 Indiana Historical Bureau and YMCA of Greater Indianapolis

ID#: 49.2016.2

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog or

Visit the Indiana History Blog or  listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about the Senate Avenue YMCA.

listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about the Senate Avenue YMCA.

Text

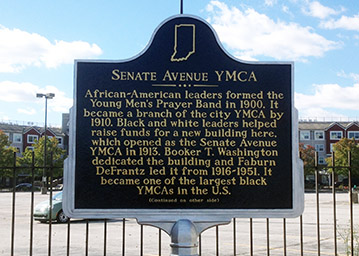

Side One

African-American leaders formed the Young Men’s Prayer Band in 1900. It became a branch of the city YMCA by 1910. Black and white leaders helped raise funds for a new building here, which opened as the Senate Avenue YMCA in 1913. Booker T. Washington dedicated the building and Faburn DeFrantz led it from 1916-1951. It became one of the largest black YMCAs in the U.S.

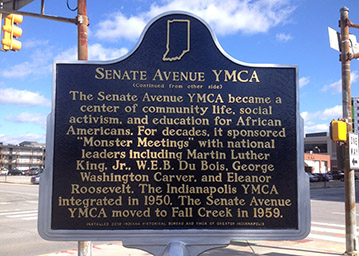

Side Two

The Senate Avenue YMCA became a center of community life, social activism, and education for African Americans. For decades, it sponsored “Monster Meetings” with national leaders including Martin Luther King, Jr., W.E.B. Du Bois, George Washington Carver, and Eleanor Roosevelt. The Indianapolis YMCA integrated in 1950. The Senate Avenue YMCA moved to Fall Creek in 1959.

Annotated Text

Side One

African-American leaders formed the Young Men’s Prayer Band in 1900.[1] It became a branch of the city YMCA by 1910.[2] Black and white leaders helped raise funds for a new building here[3] which opened as the Senate Avenue YMCA in 1913.[4] Booker T. Washington dedicated the building [5] and Faburn DeFrantz led it, 1916-1951.[6] It became one of the largest black YMCAs in the U.S.[7]

Side Two

The Senate Avenue YMCA became a center of community life, social activism, and education for African Americans.[8] For decades, it sponsored “Monster Meetings” with national leaders including Martin Luther King, Jr., W.E.B. Du Bois, George Washington Carver, and Eleanor Roosevelt.[9] The Indianapolis YMCA integrated in 1950.[10] The Senate Avenue YMCA moved to Fall Creek in 1959.[11]

[1] “Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis News, March 31, 1902, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 15, 1902 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles ; “The Y.M.C.A. in Indianapolis,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 7, 1945, Victory Progress edition, sec. 1, p. 13; “Y’s Golden,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, April 9, 1950, 6-7; George Mercer, One Hundred Years of Service, 1854-1954: A History of the Young Men’s Association of Indianapolis (Indianapolis, [1954), 83-84; Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana before 1900: A Study of a Minority (Indianapolis, 1957), 211-12, 229, 380-81; Nina Mjagkij, “Senate Avenue YMCA,” in Encyclopedia of Indianapolis ed. David Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows (Bloomington, 1994), 1249; Nina Mjagkij, Light in the Darkness: African Americans and the YMCA, 1852-1946 (Lexington, Ky,. 1994), 7, 16-18.

According to historian Emma Lou Thornbrough, in late nineteenth century Indianapolis, African Americans were not officially barred from the city’s YMCA, but no blacks had been admitted. In 1888, after two or three African Americans were denied admittance, some members proposed an amendment officially barring blacks. The amendment was tabled with understanding that very few blacks would be admitted.

In her book, Light in the Darkness, Nina Mjagkij, states that in the U.S., African Americans were generally excluded from ‘white’ branches of the YMCA but that they were also encouraged to form their own separate associations as part of the YMCA. According to George Mercer, two African American doctors in Indianapolis, H. L. Hummons and Dan H. Brown, took the first steps toward establishing their own YMCA in 1900.

At the December 1900 meeting of the Indianapolis YMCA, General Secretary, George Howser, reported that a group of African Americans had organized a Young Men’s Prayer Band. Mercer and the Indianapolis newspapers cited above list H. L. Hummons, Dan H. Brown, R. L. Sanders, Williams R. Hill, Sumner A. Furniss, Robert D. Gilliam, and Joseph H. Ward as among the founders and earliest members of the Prayer Band.

[2] “Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis News, March 31, 1902, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 15, 1902 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; 33rd Annual Report, Indiana Young Men’s Christian Association, Including Proceedings of State Convention at Peru, November 19, 20, 21, 22, 1903, (Indianapolis, 1903), 5; “Y.M.C.A.” Indianapolis World, July 12, 1913, 1; “Centennial Program to Top ‘Y’ Member Drive,” Indianapolis Star, January 9, 1954, 10 accessed Newspapers.com; George Mercer, One Hundred Years of Service, 1854-1954: A History of the Young Men’s Association of Indianapolis (Indianapolis, [1954), 84-85; Nina Mjagkij, “Senate Avenue YMCA,” in Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (Indianapolis, ed. David Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows (Bloomington, 1994), 1249.

The Indianapolis News, March 31, 1902, and the Indianapolis Recorder, April 15, 1902, both reported that the Young Mens’ Prayer Band “was merged into a colored Y.M.C.A.” International Secretary of the Y.M.C.A., J.E. Moreland was present at the meeting at Flanner Guild, March 30.The 33rd Annual Report (1903) of the Indiana Young Men’s Christian Association lists YMCA associations and dates of organization in Indiana cities through October 31, 1902. An “Indianapolis (col’r’d)” organization was established in 1902 with a total of 115 members.

George Mercer, Public Relations Director of the Indianapolis Y.M.C.A. in 1954, states that “The colored Y.M.C.A. became a branch of the Indianapolis YMCA in 1910.” The Indianapolis World, July 12, 1913, reported “On May 2, 1909, the colored work was made a branch of the local Y.M.C.A.” IHB staff has not located any primary sources to corroborate the May 1909 date.

[3] “Negro Branch Building Is Planned by Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis News, June 28, 1911; “$25,000 for the Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 1, 1911, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Work To Be Rushed on New Y.M.C.A. Home,” Indianapolis News, November 3, 1911; “$104,226.18 Raised For Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 4, 1911, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Y.M.C.A. Ground-Breaking,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 3, 1912; “Y.M.C.A. Lay Corner Stone,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 26, 1912, 1.

By 1911, the Indianapolis “colored” YMCA had outgrown its building located at California and North streets. At a joint meeting, June 27, 1911, of the Central YMCA association, the trustees and directors announced a $25,000 grant from Julius Rosenwald of Chicago to the Indianapolis YMCA for a building “to be devoted exclusively to the negroes of this city, provided the local association can raise $75,000 for a building fund.”

About three months later, the Indianapolis News and Indianapolis Recorder announced the final figure for the building fund--$104,226.18. After a ten-day campaign, “the central association had raised $59,126.15, and that the colored teams had raised $20,103.03.” Madam C. J. Walker donated $1000.00 to the effort.

The Indianapolis News, November 3, 1911, reported “J. E. Moorland, international colored YMCA secretary. . . . declared that Indianapolis had accomplished something that no other city had even attempted—the raising of a large fund directly for a colored Y.M.C.A.”

[4] “Y.M.C.A. Ground-Breaking,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 3, 1912 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Y.M.C.A. Lay Corner Stone,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 26, 1912, 1; “Indianapolis Colored Y.M.C.A. Takes Lead,” Indianapolis News, November 30, 1912, 11; “Dedication Ceremonies of Colored Y. M. C. A. Building,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 5, 1913, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Colored Y.M.C.A. To Be Inspected Sunday,” Indianapolis News, July 9, 1913; “New Spirit Is Expected from Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis News, July 9, 1913; “Y.M.C.A. Building,” Indianapolis World, July 12, 1913, p. 1, 4.

On July 28, 1912, “more than 5000 colored persons” attended the groundbreaking for the $100,000 new building located at the southwest corner of Senate Avenue and Michigan Street. On Sunday, October 20, 1912, the cornerstone of the new building was laid “with appropriate ceremony in the presence of several thousand persons.” Julius Rosenwald sent a telegram: “the chief significance of this ceremony is that the cornerstone they are laying today rests on the foundation of a more friendly mutual understanding between the two races.”

The success of the “colored” YMCA in Indianapolis, and the obvious need for a new, larger building is confirmed in the Indianapolis News, November 30, 1912: “Indianapolis now has the largest branch of the colored Y.M.C.A. in the country, there being 505 men enrolled here.”

[5] “Colored Y.M.C.A. To Be Inspected Sunday, Indianapolis News, July 9, 1913; “New Spirit Is Expected from Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis News, July 9, 1913; “Dedication Program,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 12, 1913, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Y.M.C.A. Building,” Indianapolis World, July 12, 1913, 1, 4; “Y.M.C.A. Notes,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 2, 1913, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Photograph, Senate Avenue ""Colored"" Y.M.C.A., 450 Senate Avenue, 1919 (Bass #67760-F), Digital Images Collection, Indiana Historical Society.

A week of ceremonies and festivities were held to dedicate the new Senate Avenue Y. The activities began July 6, 1913 with a public inspection of the new facility. On Monday, “Citizen’s Night,” the building was again crowded with citizens listening to the live music of Indianapolis jazz musician, Noble Sissle.

On the evening of Tuesday, July 8, Indianapolis businessman John N. Carey presided over the formal dedication ceremony during which George L. Knox, president of the “colored men’s branch” of the Y accepted the keys to the new building.

The principal speaker at the dedication, Booker T. Washington, one of the foremost African American leaders, was introduced by former U.S. vice-president and Indiana resident, Charles W. Fairbanks. Washington’s remarks, as quoted in the July 12, 1913 Indianapolis World, began with accolades:

I wish to congratulate the colored people of Indianapolis on account of this magnificent structure. I wish to thank and congratulate the white people in Indianapolis on account of their generous help and interest.

In the city of Indianapolis there are about 35,000 colored persons. Many of these have recently come here. Many are classed as ‘floaters.’ The problem which is presented by so many of our race coming into a large city like this within so short a time is a serious one. This building is to help solve this problem.

The completion of this building should mean less idleness on the part of black people in Indianapolis. It should mean less crime, less drink, less gambling, less association with bad characters. . . . Through this building every discouraged young man should be reached and a new ambition and friendly courage put into him.

At the close of the dedication ceremonies, the “Colored Men’s Good Citizens League” held a banquet in honor of Washington. Thursday night was ladies’ night, “This was particularly significant because of the fact that Madam Walker is the largest paid up subscriber among the colored people. . . . Dr. Washington was her guest while in the city.”

Reported by the Indianapolis Recorder, August 2, 1913, the Indianapolis Colored Y.M.C.A. buildings had “become the center of attraction in many ways, not only in Indianapolis, but throughout the State of Indiana.”

[6] “Y.M.C.A. Building,” Indianapolis World, July 12, 1913, 1, 4; “Tribute to ‘YM’ Head Planned for Monday, Feb. 26,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 17, 1951, 1 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “John T. James, Chicago, To Head Senate Avenue ‘Y’,” Indianapolis Star, February 10, 1952, 26; “Former YMCA and Civic Leader Dead,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 26, 1964; Mercer, One Hundred Years, 87; Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington, 2000), 26-27; Stanley Warren, “The Monster Meetings at the Negro YMCA in Indianapolis,” Indiana Magazine of History, 90 (March 1995), 59; Richard Pierce, “Little Progress ‘Happens’”: Faburn E. DeFrantz and the Indianapolis Senate Avenue YMCA,” Indiana Magazine of History vol. 108, no. 2 (June 2012), 98-103.

At the time of the dedication of the new Senate Avenue YMCA, the Indianapolis World, July 12, 1913 listed staff for the new building—among them was Faburn E. DeFrantz, the Y’s new physical director. In 1916, DeFrantz became the Executive Secretary of the Senate Avenue YMCA. For the next thirty-five years, he worked to make this segregated YMCA responsive to the educational, recreational, and social needs of the African American community in Indianapolis.

In 1933, the Indianapolis Recorder reported DeFrantz’ “determination to keep the local branch in the honor position as the colored Y.M.C.A. having the largest membership in the U.S. A.” DeFrantz was well-known across the country not only for membership development but also for his involvement in community efforts to eradicate discrimination and provide opportunities for African American boys and young men.

According to historian Richard Pierce, DeFrantz developed the Sunday afternoon “Monster Meeting” into a nationally recognized public forum where local, state, and national leaders addressed issues of the day. Pierce described the Senate Avenue YMCA as “the most significant branch in the country.” In addition to its large membership, this was “because the Y actively pursued political education, because it served as an agent for city-wide desegregation efforts, and because it had Faburn DeFrantz, a leader who believed that the YMCA could be a vanguard for change in the city and state.”

DeFrantz played a crucial role in desegregating Big 10 college basketball in 1946 and 1947. When DeFrantz retired in 1951, the Indianapolis Recorder described him as “an enterprising and inspiring leader of young men. . . . Men aided or inspired by the man, DeFrantz, are now scattered to the four winds and found in almost all walks of life.” For more information about IU and Big 10 basketball, see Indiana Historical marker for Bill Garrett.

Note: A portion of DeFrantz’ memoir is published in the June 2012 issue of the Indiana Magazine of History, “To Kathy and to David”: The Memoir of Faburn E. DeFrantz.”

[7] “Colored Y.M.C.A. Grows,” Indianapolis Star, May 5, 1909, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; “Negro Branch Building Is Planned by Y.M.C.A.” Indianapolis News, June 28, 1911; “Indianapolis Colored Y.M.C.A. Takes Lead,” Indianapolis News, November 30, 1912, p. 11; “Y.M. Plans to Retain First Place in Annual Drive,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 22, 1934 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “A tribute to a Citizen,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 6, 1943, 10, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Senate Ave. Branch Here Is One of the Largest in the World,” Indianapolis Times, April 4, 1947; “Senate Avenue Y Largest in State,” Indianapolis News, April 14, 1948; “Y’s Golden Jubilee,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, April 9, 1950, 6-7; Nina Mjagkij, “True Manhood: The YMCA and Racial Advancement, 1890-1930,” in Nina Mjagkij and Margaret Spratt, eds., Men and Women Adrift: The YMCA and YWCA in the City (New York University Press: 1997), 142; Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Indiana University Press: 2000), 4, 35, 116, 190; Campbell Gibson and Kay Jung, “Historical Census Statistics On Population Totals By Race, 1790 to 1990, and By Hispanic Origin, 1970-1990. For Large Cities and Other Urban Places in The United States,” in U.S. Census Bureau, Population Division, Working Paper No. 76 (Washington D.C.: February 2005) accessed www.census.gov.

Historian Nina Mjagkij states: “The tremendous growth of black YMCA work at the turn of the century was largely the product of the increasing migration of African Americans from the countryside to the cities.” This migration included African Americans leaving southern cities and plantations “searching for employment and educational opportunities as well as a less racially oppressive environment.”

According to Indiana historian Emma Lou Thornbrough, in 1900 Indianapolis had the largest concentration of African Americans in the state. Indianapolis also had one of the highest percentages of blacks in northern cities. The continuous growth of the Indianapolis African American YMCA membership parallels the growth of the city’s black population.

As early as May 1909, the “colored department of the Indianapolis Y.M.C.A.” was described by the Indianapolis Star as “the largest in the United States.” Its membership had grown from 186 to 400. One of the primary motivations for building the Senate Avenue YMCA was the rapid increase in membership. Over the next thirty-five years, the membership rolls of the African American Y in Indianapolis continued to be among the largest in the United States.

On the fiftieth anniversary of the Indianapolis “colored” YMCA, the Indianapolis Star Magazine reported the growth of members by year: 1903—52, 1913—440; 1923—2173; 1933—2610; 1944—4000+, 1950—5134.

[8] “Colored Y.M.C.A.,” Indianapolis News, March 31, 1902, 2 accessed Newspapers.com; “The Indianapolis ‘Y’,” The Crisis, March 1924, 205-208 accessed GoogleBooks.com; “Y’s Golden Jubilee,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, April 9, 1950, 6; Warren, “The Monster Meetings,” 57-80; “Backing Faith with Action,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, November 14, 1954, p. 28-29; George C. Mercer, “One Hundred Years of Service 1854-1954 (Indianapolis: n.d.), 83-89; Nina Mjagkij and Margaret Spratt, eds., “Introduction,” Men and Women Adrift: The YMCA and YWCA in the City (New York University Press: 1997), 12; Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington, 2000), 31, 32, 44-45, 65, 74, 83, 99.

Authors Mjagkij and Spratt remind readers that the YMCA in the U.S. remained segregated until 1946. Even so, the black YMCAs “played a crucial role in the struggle for racial advancement. . . . [they] launched programs that fostered self-respect and self-reliance and tried to provide young men with proper role models and male companionship. . . . [they] served as sanctuaries which preserved African American masculinity and prepared black men and boys for their leadership role in the struggle for equality that lay ahead.”

In segregated Indianapolis in 1913, author George Mercer states that: “The colored community had assumed the responsibility for its own recreation and charity work, with some assistance from the Whites.” This same community established the “colored” YMCA” and developed its programs and services to benefit the ever-increasing African American population of Indianapolis.

Thornbrough reports that the Senate Avenue Y served as a headquarters for recruitment of black and white volunteers during WWI. Afterward, the Y expanded education and recreation programs. The Senate Avenue building provided meeting space for many different community organizations and for the informational and educational Monster Meetings. When the Depression affected the public school system’s night classes, the Senate Avenue Y offered free classes to all. During WWII, the Senate Avenue building became the headquarters for the planning of services and programs for African American servicemen in the city.

By 1924, the NAACP magazine, The Crisis, reported that the Indianapolis black YMCA had worked hard in their “attempt to engender a better racial feeling between the citizenry.” Still self-supported, the Senate Avenue Y raised their entire 1923 budget except for a small Community Chest donation. Also, the Boys’ Division of the Y had raised funds to provide over 700 memberships to those who could not afford to join. The article concluded by stating that the “greatest benefit is the part played by the organization in building up a racial consciousness of ability to achieve and administer large enterprises and the subsequent strengthening of mutual confidence.”

[9] “Dr. W.E.B. Dubois, Prominent Race Leader Airs Views on Segregation in Visit Here. . . ,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 17, 1934, 1, 8 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Back U.N., Mrs. Roosevelt Pleads Here,” Indianapolis Times, December 14, 1953, sect. 1, p. 20; “Du Bois to Speak,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 8, 1941; “Mrs. Roosevelt on Monster Meeting List,” Indianapolis News, October. 15, 1953; “Warm Welcome Awaits Eleanor Roosevelt,” Indianapolis Recorder, December 11, 1953; “Backing Faith With Action,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, November 14, 1954, 28-29; Stanley Warren, “The Monster Meetings at the Negro YMCA in Indianapolis,” Indiana Magazine of History, 90 (March, 1995), 57-80; Richard Pierce, “Little Progress ‘Happens’ Faburn e. DeFrantz and the Indiana Senate Avenue YMCA,” Indiana Indiana Magazine of History, vol. 108, no. 2 (June 2012), 98-103.

According to the 1954 Indianapolis Star Magazine, Thomas E. Taylor, executive secretary of the “colored department” of the Indianapolis YMCA, established the “Monster Meeting” public forum in 1904. Originally the meetings were very religious in nature but when Faburn DeFrantz took over direction of the Senate Avenue Y in 1916, he expanded the meetings to include “free discussion of all subjects of human interest” and to offer opportunities for black youth “to see and hear social leaders from an inspiration standpoint.”

Historian Richard Pierce states that the Indianapolis Senate Avenue YMCA “became known nationally for the Sunday afternoon meetings [the Monster Meetings] in which dignitaries, politicians, and scholars—local, regional, and national—took to the stage to inform interested and large audiences of the issues of the day. . . . The Monster Meetings were the focal point for protest and constituent education in Indianapolis, but the impact of those who were educated on those Sunday afternoons was felt throughout the state.”

Some of the prominent individuals to speak at Monster Meetings included Max Yergan, Walter White, Alain Locke, Mordecai Johnson, George Washington Carver, Booker T. Washington, Lillian Smith, A. Phillip Randolph, Adam Clayton Powell, Benjamin E. Mays, Thurgood Marshall, Jackie Robinson, Countee Cullen, George W. Cable, George S. Schuyler, Charles S. Johnson, Herman B Wells, Hale Woodruff, Jesse Owens, Roy Wilkins, E. Franklin Frazier, Paul Robeson, Langston Hughes, Jersey Joe Walcott, and Ralph F. Gates.

For a more complete list of speakers and dates, see Warren, “The Monster Meetings,” 66-80.

[10] YMCA Adopts Recommendation To Drop Racial Segregation,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 23, 1946; “Senate Avenue YMCA Marks 50th Year,” Indianapolis News, December 2, 1950.

At the 45th International Convention of the Young Men’s Christian Associations of North America in 1946, the National YMCA adopted “a recommendation to abandon all racial bars in religious, social and athletic activities” and called on its local associations to desegregate.

In Indianapolis at the December 1950, fiftieth anniversary celebration of the Senate Avenue branch of the YMCA, Parker Jordan, general secretary of the metropolitan board of the YMCA and F. E. DeFrantz, secretary of the Senate Avenue branch, announced “that the board had erased the work Negro from its by-laws and that barriers of race or color had been dropped.”

[11] “Y’s Golden Jubilee,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, April 9, 1950, 6; “New ‘Y’ Building Planned Here,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 13, 1952, 1 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Perfect Plans for New Senate Avenue YMCA,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 26, 1955, 1, 3; “Groundbreaking Held For $1,000,000 ‘Y’,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 19, 1958 1, 3; “New YMCA Evidence Of Interracial Goodwill,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 17, 1958, 10; “Preview of New Y Unit Given,” Indianapolis News, September 8, 1959; “New Million-Dollar YMCA Open for Activities,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 12, 1959, 1, 8; “New Home of the Senate Avenue YMCA,” Indianapolis Star Magazine, September 13, 1959, 48; “Y’s ‘Big Soul’ Enters Glamorous New Body,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 19, 1959; “Fall Creek Y Fighting to Stay Alive,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 17, 2000, 1; Amos Brown, “Just Tellin’ It,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 30, 2001, 10; “Fall Creek YMCA To Close September 30,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 27, 2003, 1; “Fall Creek YMCA Closes, Symbolic of Changing City,” Indianapolis Star, October 1, 2003, B1, B5.

With over 5,000 members in 1950, the Senate Avenue YMCA building was bursting at its seams. The September 13, 1952 Indianapolis Recorder reported that discussion was underway for replacing the Senate Avenue Y with a new, modern building. A fund drive to raise $1.5 million was announced in January 1953; $690,000 would be allocated to a new Senate Avenue YMCA.

The Recorder (November 1955) reported that the new YMCA would be constructed at West 10th St. at Fall Creek Parkway and Indiana Avenue; projected costs had increased to $950,000. At the groundbreaking ceremony held in April 1958, the Recorder reported that the Fall Creek YMCA represents: “The ideal of finer young manhood shared by Indianapolis people without regard for race, color or creed.”

When the new Fall Creek YMCA was dedicated, September 13, 1959, it was “hailed as a tribute to Executive Secretary John J. James . . . and to the Indianapolis public whose faith, work and money made the project possible.” This new facility “has made up its mind to cross the color line in the dormitory, the swimming pool and everywhere,” reported by the Recorder, September 19, 1959.

Forty years later, the Fall Creek YMCA was fighting to stay open. Fewer adult memberships and migration of nearby population away from the inner city resulted in growing annual budget deficits. The Indianapolis Recorder reported in March 2001 that the 2000 Census showed two-thirds of the city’s African American population living outside of Center Township. In June 2003, the Metropolitan Board of the Indianapolis YMCA passed a resolution to close the Fall Creek YMCA on September 30, 2003. The Indianapolis Star reported, October 1, 2003, “Fall Creek YMCA closes, symbolic of a changing city.” The article cited construction of Interstate 65 and the expansion of the IUPUI campus as additional factors in the Y’s declining membership.

Keywords

African American, Education, Buildings & Architecture