Location: 38 East 3rd Street, directly behind the 2nd Baptist Church, New Albany, IN 47150 (Floyd County, Indiana)

Installed 2011 Indiana Historical Bureau and Friends of Division Street School, Inc.

ID#: 22.2011.1

Text

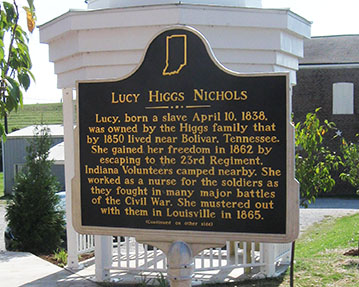

Side One:

Lucy, born a slave April 10, 1838, was owned by the Higgs family that by 1850 lived near Bolivar, Tennessee. She gained her freedom in 1862 by escaping to the 23rd Regiment, Indiana Volunteers camped nearby. She worked as a nurse for the soldiers as they fought in many major battles of the Civil War. She mustered out with them in Louisville in 1865.

Side Two

Lucy came to New Albany with returning veterans of 23rd Regiment. She married John Nichols, 1870. Lucy applied for pension after Congress passed 1892 act for Civil War nurses; she was denied. In 1895, Lucy and 55 veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress; in 1898, a Special Act of Congress awarded her pension. Lucy was an honorary member of the G.A.R. She died 1915.

Annotated Text

Side One:

Lucy, born a slave April 10, 1838,[1] was owned by the Higgs family that by 1850 lived near Bolivar, Tennessee.[2] She gained her freedom in 1862 by escaping to the 23rd Regiment, Indiana Volunteers camped nearby. [3] She worked as a nurse for the soldiers[4] as they fought in many major battles of the Civil War.[5] She mustered out with them in Louisville in 1865.[6]

Side Two:

Lucy came to New Albany with returning veterans of 23rd Regiment.[7] She married John Nichols, 1870.[8] Lucy applied for pension after Congress passed 1892 act for Civil War nurses;[9] she was denied.[10] In 1895, Lucy and 55 veterans of the 23rd petitioned Congress;[11] in 1898, a Special Act of Congress awarded her pension.[12] Lucy was an honorary member of the G.A.R.[13] She died 1915.[14]

[1] Inventory of Property of Winniford Amanda Higgs, submitted to court, Yalobusha Co., Mississippi by S.G. Wheless, guardian, March 2, 1846, Probate Records, Coffeeville, Mississippi, copy from applicant.

Lucy, 8 years old, born April 10, 1838, along with Aaron and Angelina were listed as property belonging to Winnaford Amanda Higgs, minor heir of Reuben Higgs Dec’d.

[2] Title Bond, April 1, 1839, Hardeman Co., TN Deed Book H, pp. 336-37, copy from applicant; Hardeman County, Tenn., Cemeteries, Higgs Cemetery, Hardeman County Tennessee Archives-Cemeteries; John Higgs, Petition, January 6, 1847, Probate Court, Yalobusha Co., Miss. copy from applicant; Court Order, March Term 1848, Yalobusha County, Miss. copy from applicant; Inventory of Effects of Winiford A Higgs, January Term 1849, Hardeman Co., Tenn. Records, Book 4, page 564, copy from applicant; Inventory of Effects of Winiford Amanda Higgs, minor heir of Reuben Higgs, deceased, March 2, 1846, copy from applicant; Settlement, Jno. Higgs, Adm., W. A. Higgs, February Term 1849, Hardeman Co., Tenn. Records, Book 4, page 567, copy from applicant; Inventory of Property of Minor Heirs of Reuben Higgs. Hardeman Co., Tenn. Records, June 9, 1855, 381, copy from applicant; Petition to Divide Land and Slaves, Minute Book #10, Hardeman County Court, January 8, 1861, copy from applicant.

Reuben Higgs and Elizabeth, his second wife, came to Hardeman County, Tennessee circa 1836; Higgs, from Halifax Co., North Carolina purchased property in Hardeman Co., Tennessee in 1839. Elizabeth died 1844 and Reuben died May 1845.

“Slaves for life,” Lucy, Aaron, and Angeline were listed as part of Eliza Higgs’ (Rueben’s first wife) estate passing to [Winnaford] Amanda, oldest child of Reuben and Eliza Higgs. Amanda died May 1847. John Higgs, the guardian of Willie, Marcus, and Prudence, who were the half-siblings of Amanda Higgs, filed suit and claimed “Negro property” that Samuel G. Wheless (Amanda’s former guardian) refused to deliver. Lucy, Aaron, and Angelina, “property of Winnaford Amanda Higgs, dec’d” were ordered delivered to Theophilus Higgs and received from Samuel G. Wheless, April 14 [1848]. The three were recovered from Wheless in Yalobusha County, Mississippi, and taken to Hardeman County, Tenn., as the property of Wilie, Marcus, and Prudence Higgs as administered by John Higgs.

[3] Congress, Second Confiscation Act, July 17, 1862, accessed Freedmen & Southern Society Project, University of Maryland, http://www.history.umd.edu/Freedmen/conact2.htm; W. H. H. Terrell, Report of the Adjutant General of the State of Indiana, 8 vols. (Indianapolis, 1866), 2:227-28; New Albany Daily Ledger, December 13, 1898; New Albany Daily Ledger, July 27, 1865; Ella Forbes, African American Women during the Civil War (New York: Garland Publishing, Inc: 1998), 9-61; David Williams, A People’s History of the Civil War: Struggles for the Meaning of Freedom (New York: The New Press, 2005), 343-6.

“Lucy was born a slave and continued in slavery until she was twenty years old, when she joined the Twenty-third at Bolivar, Tenn., and thus secured her freedom,” according to the New Albany Daily Ledger, December 13, 1898. The 23rd Regiment, Indiana Volunteers was organized and mustered into service at New Albany, July 29, 1861. The regiment engaged Confederates at Shiloh, Tenn., spent summer 1862 camped at Bolivar, Tenn., then participated in sieges at Vicksburg and Atlanta as well as Sherman’s March to the Sea. They were mustered out at Louisville, Kentucky, July 23, 1865. Ages of individuals are reported as they appear in the primary sources.

Thousands of enslaved African Americans emancipated themselves by heading to Union lines in what W.E.B. Du Bois called “a general strike against the confederacy.” Many went to work in service of the Union, the men mainly as laborers or soldiers, the women as laundresses, cooks, nurses, and even spies. By the time Congress passed the Second Confiscation Act July 17, 1862, the United States Army officially considered formerly enslaved peoples working behind Union lines as “contraband.” Considered spoils of war, they were given protection by the U.S. government to prevent them from contributing to the Southern labor force. According to historian Ella Forbes, defining them as contraband “allowed the denial of basic civil rights to the African Americans who had liberated themselves by fleeing enslavement” and placed the formerly enslaved “at the mercy of a generally racist bureaucracy which exploited their labor and humanity.”

By escaping the Higgs family, and fleeing to the regiment camped in Bolivar, Lucy became a “captive of war” as described in the Act.

[4] Declaration for Nurse’s Pension, September 5, 1892, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant.

According to her application for nurse’s pension, Lucy “was employed as Nurse by assignment on or about the 1st day of July, 1862 in the Regimental Hospital of 23rd Regt. Indiana vols then in camp at Bolivar Tenn.” She stated that she was “honorably released at Indianapolis, Indiana on or about the 23rd day of July 1865.”

[5] Terrell, 2:227-28.

[6] Terrell, 2:227-28; Indianapolis Daily Journal, July 26, 1865, 4, 3.

[7] “’Mammy’ Lucy Nichols Member of the G.A.R.,” Washington Times, June 19, 1904, 7, accessed through Chronicling America, Library of Congress; ”Twenty-Third,” New Albany Tribune, October 7, 1910; “Why Aunt Lucy Got a Pension,” Denver Evening Post, December 18, 1898, 22, accessed through 19th Century U.S. Newspapers; Photograph, Veterans of the Civil War and Spanish-American War, English, Indiana, circa 1898, accessed through New Albany Floyd County Public Library, copy from applicant.

Special Note: The term “aunt,” used to describe Nichols, is part of the “mammy” myth, and is an extension of the “loyal slave” myth. The aunt/mammy stereotype depicts a desexualized, African American woman who happily serves and cares for whites and was constructed (through southern white nostalgia) to assert the inferiority African American women.

For more information see: M.M. Manring, Slave in a Box: The Strange Career of Aunt Jemima (Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998); Kimberly Wallace-Sanders, Mammy: A Century of Race, Gender, and Southern Memory (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2008); Kimberly Wallace-Sanders , “Southern Memory, Southern Monuments, and the Subversive Black Mammy,” Southern Spaces, June 15, 2009, accessed http://www.southernspaces.org/2009/southern-memory-southern-monuments-and-subversive-black-mammy; David Pilgrim, “The Mammy Caricature,” Museum of Racist Memorabilia, Ferris State University, accessed http://www.ferris.edu/jimcrow/mammies/.

[8] Copy of Marriage License, John H. Nichols to Lucy Higgs, April 13, 1870, Floyd County, Indiana, Floyd County Circuit Court, copy from applicant; Deed of Sale from John H. Stotsenbourg and Jane M. Stotsenbourg to John Nichols, January 2, 1871 (recorded March 5, 1872), Floyd County, Indiana, Deed Book 19: 30, copy from applicant; Will of John Nichols, November 11, 1910, Floyd County, Will Book G: 225, copy from applicant; Election of Widow, March 11, 1911, Floyd County Will Book G: 256 (copy from applicant); New Albany, Indiana, City Directories. Publishing Co., [1880-1881, 1911-1912, 1913-1914]; “Why Aunt Lucy Got a Pension,” Denver Sunday Post, December 18, 1898, 22, accessed through 19th Century U.S. Newspapers; William Pencak, Encyclopedia of the American Veteran, vol. 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2009), 525-26.

Married April 13, 1870, John and Lucy Nichols lived on Nagel Street in New Albany, after John purchased land there in 1871. According to the New Albany city directories, John worked as a laborer. After John’s death in 1910, Lucy remained in New Albany, as a boarder and as a laundress, according to New Albany City Directories. See Denver Sunday Post article for more information Nichols’ residences and occupations.

[9] United States Congress, “Act August 5, 1892 Pensions to Army Nurses,” Laws of the United States Governing the Granting of Army and Navy Pensions, (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1919), 27, accessed GoogleBooks.

[10] Correspondence, War Department Record and Pension Division to Department of Interior, Bureau of Pensions, October 22, 1892. Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; Lorenzo D. Emory, General Affidavit, January 14, 1893, Spencer Byrn, General Affidavit, January 19, 1893, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; Lucy Nichols, General Affidavit, July 29, 1893, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; Lucy Nichols, General Affidavits, November 8 and December 11, 1893, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; Dr. William A. Burney, General Affidavit, January 4, 1894, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; Invalid Pension Claim Form, September 7, 1892. Lucy Nichols, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copies from applicant.

When Nichols applied for her pension (after Congress passed the 1892 Nurses’ Pension Act) the Record and Pension Division of the War Department claimed they found no records of employment or payment for her. Starting in 1893, several veterans of the 23rd Regiment submitted affidavits on Nichols’ behalf. In July 1893, she sent an affidavit providing information that she had never been paid for her work. She sent affidavits that responded to additional questions from Pension Office in November and December, 1893. Nichols’ physician, Dr. William A. Burney, sent an affidavit describing her medical problems. Nichols’ claim was rejected in January 1894 but resubmitted for “special examination” in March 1894. On June 27, 1894, her claim was again rejected because “claimant not employed as a nurse by proper authority of the War Dept.”

[11] United States Congress, “Pension for Lucy Nichols,” U.S. Serial Set, House Report No. 1397, Fifty-Fifth Congress, Second Session, May 23, 1898, accessed through HeritageQuestOnline.

The petition sent to Congress by Nichols and members of the 23rd Indiana Regiment was sent December 19, 1895 by Benjamin F. Welker to R. J. Tracewell, M.C., Washington, D.C.

[12] New Albany Daily Ledger, December 13, 1898; “Pension for Lucy Nichols,” New York Times, December 14, 1898, accessed through New York Times Archives; Copy of Act, Department of Interior, December 28, 1898, Lucy Nichols, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; United States Congress, “Lucy Nichols,” House Report No. 1397, Fifty-fifth Congress, Second Session, p. 1-3, accessed through Heritage Quest Online; Lucy Nichols, Pension Record Re-Opened December 20, 1898 Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; Lucy Nichols, Invalid Pension, submitted January 5, 1899, Lucy Nichols, Nurse’s Claim #1130541, National Archives, copy from applicant; “A Female Civil War Veteran,” New York Times, December 27, 1898, accessed through New York Times Archive; New Albany Daily Ledger, Jan. 26, 1899.

According to a December 13, 1898 article in the New Albany Ledger, Congressman W. T. Zenor pushed this Special Act granting Nichols a pension of $12 through Congress. On December 20, 1898, “An Act Granting a pension to Lucy Nichols” was approved and Nichols’ Pension Application was re-filed. According to a December 27, 1898 New York Times article, Lucy had been notified that President McKinley signed the act. Nichols’ pension application was approved for admission January 6, 1899. January 26, 1899, the New Albany Daily Ledger reported that the Pension Commissioner ordered checks issued for her pension, including back pay, via a Special Act of Congress.

[13] “Why Aunt Lucy Got a Pension,” Denver Evening Post, December 18, 1898, 22, accessed through 19th Century U.S. Newspapers; “Colored Nurse’s Pension,” Logansport (Indiana) Daily Journal, July 15, 1898, 5; “Pension for Lucy Nichols,” New York Times, December 14, 1898, accessed through New York Times Archives; William Pencak, Encyclopedia of the American Veteran, vol. 1 (Santa Barbara, CA: ABC-CLIO, 2009), 525-26.

For information on the GAR (Grand Army of the Republic, see http://www.loc.gov/rr/main/gar/ .

[14] Registration for Lucy Nichols, admitted January 5, 1915, died January 29, 1915, Floyd County Asylum Register copy from applicant; Death Record for Lucy Nichols, January 29, 1915, Floyd County Death Record, Book H10-2, p. 70; New Albany Weekly Public Press, February 2, 1915; New Albany Weekly Times, February 5, 1915; New Albany Weekly Ledger, Feb. 5, 1915.

According to the Floyd County Asylum Register, she entered the asylum (likely for medical care) January 5, 1915 and died there January 29, 1915. According to the Floyd County Death Record, Nichols died of “paralysis and senility” and was buried in the “Colored Cemetery.” According to the New Albany Weekly Ledger, the GAR organized her funeral; she was buried with military honors beside her husband.

Keywords

Women, African American, Military, Medicine