Location: Green space east of the Westin Indianapolis Hotel, between Maryland St. and Washington St., Indianapolis, IN 46204 (Marion County, Indiana). Marker replaces 49.1979.1 Indianapolis Times.

Installed 2013 Indiana Historical Bureau, Hoosier State Press Association Foundation, Marion County Historical Society, and Friends

ID#: 49.2013.2

Listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about the KKK, political corruption in the 1920s, and the Indianapolis Times.

Listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about the KKK, political corruption in the 1920s, and the Indianapolis Times.

Text

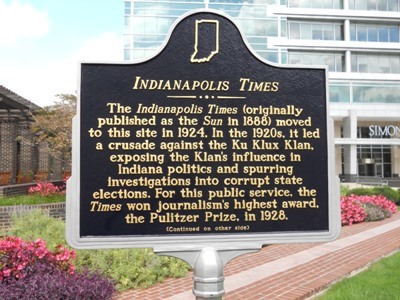

The Indianapolis Times (originally published as the Sun in 1888)1 moved to this site in 1924.2 In the 1920s, it led a crusade3 against the Ku Klux Klan,4 exposing the Klan's influence in Indiana politics5 and spurring investigations into corrupt state elections.6 For this public service, the Times won journalism's highest award, the Pulitzer Prize, in 1928. 7

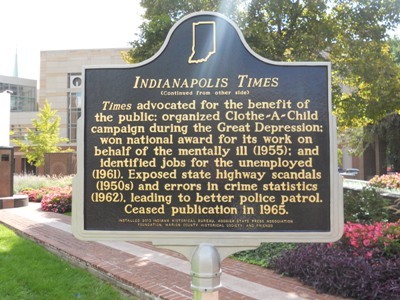

Times advocated for the benefit of the public: organized Clothe-A-Child campaign during the Great Depression;8 won national award for its work on behalf of the mentally ill (1955);9 and identified jobs for the unemployed (1961).10 Exposed state highway scandals (1950s)11 and errors in crime statistics (1962), leading to better police patrol. 12 Ceased publication in 1965.13

Annotations

[1] "Introductory," [Indianapolis] Sun, May 12, 1888; Indianapolis Sun, October 21, 1899; [Indianapolis] Evening Sun, January 29, 1913; "Indiana Daily Times New Name of the Evening Sun: 'You Hit Her,' Says Pat, 'I Ain't Got the Heart,'"Evening Sun, July 18, 1914, n.p.; "On These Principles the INDIANA DAILY TIMES Shall Build Its Future,"Indiana Daily Times, July 20, 1914, 1; Indianapolis Times, June 26, 1922, 1; "The Times Crusaded for the Public," Indianapolis Times, October 11, 1965, 1; Miller, John W. Indiana Newspaper Bibliography (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1982), 286-287; David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, eds., The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 811; "About the Sun," Library of Congress, Chronicling America; "About the Indianapolis Sun," Library of Congress, Chronicling America; "About the Evening Sun," Library of Congress, Chronicling America; "About Indiana Daily Times," Library of Congress, Chronicling America; " About the Indianapolis Times," Library of Congress, Chronicling America.

According to John Miller's Indiana Newspaper Bibliography, the newspaper was first published as the Sun in 1888. Records from the Library of Congress, which chronicle the evolution of the Times, indicate that the Sun ran until 1899, at which time it became the Indianapolis Sun. The name changed again in 1913 to the Evening Sun and in 1914 to the Indiana Daily Times. In 1922, Scripps-McRae Newspapers (later Scripps-Howard) purchased the paper and changed its name to the Indianapolis Times. It held this name until it ceased publication in 1965.

Note: Colonel W.R. Holloway started a morning daily named the Indianapolis Times in 1881 that was acquired by the Indianapolis Journal in 1886; it is not the same as the Times referred to on this marker.

[2] "Indianapolis, IN," Sanborn Fire Insurance Map, #152, 1898, accessed atIUPUI Digital Collections; "TheIndianapolis Sun," Indianapolis Sun, February 2, 1910, Editorial Page; "Indianapolis, IN,"Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1914-August 1950 - Indianapolis, 1914, Indiana State Library; "Indianapolis, IN," Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 1950-1970 - Indianapolis, Indiana State Library; "Times is in New Home," Indianapolis Times, February 25, 1924, 1; Indianapolis Star, February 27, 1924, 6, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Construction Starts on New Times Building," Indianapolis Times, January 4, 1949, 1; "$1,150,000 Building Expansion Completed By Times ," Indianapolis Times, April 2, 1950, 21; "The Times Crusaded for the Public," Indianapolis Times, October 11, 1965, 1.

According to a February 1924 Times article, the newspaper moved to its new home at 214-220 West Maryland Street and began publishing there on February 25, 1924. Prior to this, the paper was published at 25-29 South Meridian Street. Additions to the 214-220 West Maryland building were made in 1949. A January 4, 1949 Times article reported, "one full floor will be added to the present two-story building and the entire three-story structure will be extended from the rear of the present building to Pearl Street." Construction was completed in 1950. A 1965 Times article reported that the building was the home of the newspaper from 1924 throughout the remainder of its publication.

[3] "History of Crusade Waged by the Times Against Corruption in State Government," Indianapolis Times, May 8, 1928, 1-2; John Bartlow Martin, "Beauty and the Beast: The Downfall of D.C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of the Indiana K.K.K.," Harper's Magazine, September 1944, 328; "The Times Crusaded for the Public," Indianapolis Times, October 11, 1965, 1; James H. Madison, Indiana Through Tradition and Change: A History of the Hoosier State and Its People, 1920-1945 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1982), 52, 70; "Defunct Paper's Staffers Will Recall Old Times," Indianapolis Star, 1990, Frank N. Widner Papers, 1939-2003, Manuscript and Visual Collections Dept., Indiana Historical Society, M1001, Box 1, Folder 5; M. William Lutholtz, Grand Dragon: D.C. Stephenson and the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1991), 72, 211; David J. Bodenhamer and Robert G. Barrows, eds., The Encyclopedia of Indianapolis (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 811.

The Times used the word "crusade" to describe many of the campaigns it fought on behalf of the public. In particular, the paper associated the word with its fight against the Ku Klux Klan and corruption in state politics and published an article in May 1928 entitled, "History of Crusade Waged by the Times Against Corruption in State Government." In its last issue in 1965, a Times headline read "TheTimes Crusaded for the Public." See footnotes 5 and 6 for information regarding its crusade against the KKK. For other examples of the Times' crusades see footnotes 9, 11, and 12.

[4] For information on the Ku Klux Klan, particularly its work in Indiana during the 1920s, see Kenneth T. Jackson,The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967); Leonard J. Moore, Citizen Klansmen: The Ku Klux Klan in Indiana, 1921-1928 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1991), accessed Google Books ; William M. Lutholtz, Grand Dragon: D.C. Stephenson and the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1991), accessed Google Books ; David Horowitz, ed., Inside the Klavern: The Secret History of the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s (Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1999).

See http://www.in.gov/library/2848.htm for a listing of sources on the KKK at the Indiana State Library.

The Ku Klux Klan, referred to by many as the Invisible Empire, originated in Tennessee in 1866 as a secret group within the former Confederacy. The group dissipated by 1877, but was revived in 1915. According to David Horowitz in Inside the Klavern, the Klan "attract[ed] between two million and six million members in the years after World War I." Composed of native-born, white Protestants, the Klan supported nativism, racism, Americanism, and temperance. Members specifically opposed hyphenated ethnicities that joined two ethnic or racial backgrounds. Among its targets were African Americans, Roman Catholics, Jews, Asian Americans, and immigrants.

[5] Indianapolis Times , April 13, 1923, 1; Indianapolis Times, July 4, 1923, 1; "No Secret Order Shall Rule Indiana!," Indianapolis Times, November 1, 1924, 1; "Choose," Indianapolis Times, November 3, 1924, 1; "Klan Edict Out; Asks Members to Vote Republican," Indianapolis Times, November 3, 1924, 12; "The Election-The Klan-The Future," Indianapolis Times, November 5, 1924, 1; "Ed Jackson and Entire State Ticket Swept in by Republican Landslide," Indianapolis Times, November 5, 1924, 1; "Gentlemen from Indiana," TIME Magazine, October 18, 1926, 12; Kenneth T. Jackson, The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1967).

During the 1920s, the Klan gained a large following in Indiana. According to Kenneth Jackson in The Ku Klux Klan in the City, "from 1922 to 1925, Indianapolis was the unrivaled bastion of the Invisible Empire in Mid-America." The Klan's popularity in the state was due in part to D.C. Stephenson. Stephenson attracted thousands of individuals to the Klan while serving as Grand Dragon of Indiana, the highest ranking position in the organization in a given state. He also played a significant role in getting the KKK involved in Indiana politics.

As early as 1923, the Times printed articles describing Klan rallies in the state and in an April 13, 1923 article it described how Ed Jackson, Secretary of State at the time, had been called out as a Klan member by the anti-Klan publication Tolerance. In 1924, the KKK began campaigning for Republican candidates and votes for Jackson in the gubernatorial election that year. On November 3, 1924, the Times published an article which read, "A proclamation signed by the grand dragon . . . is being distributed by Klansmen urging voters to uphold the Republican ticket and setting out object of the Klan at the Tuesday election." The article detailed the Klan's program and reported that "the Republican organization and practically all of its candidates ha[d] pledged themselves to [it]." This program included exclusion of foreign immigrants, white supremacy, the segregation of African Americans, and "appointment to various offices of only Klansmen, Klanswomen, or sympathizers." The Times wrote on November 1, 1924, "that no secret order whose proclaimed purpose is to control the civil government should be tolerated." Further, the paper vowed to fight any such club, church, or organization that sought to run the state, declaring that "the Times would consider itself worse than cowardly if it did not do everything in its power to check that purpose before it is too late." Making its stance in the gubernatorial race even clearer, the paper declared that "a vote for Jackson is a vote for the Invisible Empire. A vote for [Carleton] McCulloch is a vote against."

The 1924 election resulted in a big win for Republicans, with Jackson elected governor of the state. In a November 5, 1925 article, the Times repeated its earlier plea that the Klan remove itself from Indiana politics and expressed its hope that Jackson would "shake off the influence of the Ku Klux Klan." Additionally, it wrote that "if the Klan should begin to exercise its influence in the Statehouse, the Times will fight it to the last ditch." Readers would see this fight come to fruition in 1927 when the details of the 1924 election and the extent of the political corruption in Indiana were brought to light by the newspaper. See footnote 6 for further information.

[6] "Stephenson Plot Bared by Editor," Indianapolis Times, September 28, 1926, 1; "The Stephenson Scandal," Indianapolis Times, October 4, 1926, 1; "Stephenson Dismisses Ira Holmes," Indianapolis Times, October 5, 1926, 1, 11; "An Open Letter," Indianapolis Times, October 5, 1926; "Jackson Enters Denial in 'Steve' Garnishee Case," Indianapolis Times, May 10, 1927; "Steve's Offer to Talk Fails to Stir Remy," Indianapolis Times, June 29, 1927, 1; Boyd Gurley, "Stephenson Fights for Release, But Withholds All Political Secrets," Indianapolis Times, July 1, 1927, 1; "'Black Box' Yields Check from Steve to Jackson, for Primary Expense Use," Indianapolis Times, July 11, 1927, 1; "Steve Depends on the Times to Print Story," Indianapolis Times, July 11, 1927; "More Checks Back Steve's Expose Story," Indianapolis Times, July 12, 1927, 1; "Steve Checks Used to Win Negro Votes,"Indianapolis Times, July 13, 1927, 1; "Governor Admits Receiving Check from Stephenson; Pay for Horse, He Insists," Indianapolis Times, July 14, 1927, 1; "Now for the Clean Up," Indianapolis Times, July 27, 1927; "Jackson Mum on Story of M'Cray Offer," Indianapolis Times, July 27, 1927, 1; "Times Turns Over Checks to Jurors," Indianapolis Times, July 27, 1927, 1; "Is There One Man?," Indianapolis Times, August 12, 1927; "Jackson Acquitted by Order of Court," New York Times, February 17, 1928, 1; "Jackson Acquitted by Order of Court," New York Times, February 17, 1928, 1; "History of Crusade Waged by the Times Against Corruption in State Government," Indianapolis Times, May 8, 1928, 1-2.

The results of the 1924 gubernatorial election shed light on the Klan's influence in Indiana politics and illustrated D.C. Stephenson's power within the state. By 1925 though, Stephenson's hopes for the Klan faded when he was indicted, tried, and convicted of second-degree murder in the case of Madge Oberholtzer. For information on the case, see John Bartlow Martin, "Beauty and the Beast: The Downfall of D.C. Stephenson, Grand Dragon of the Indiana K.K.K.," Harper's Magazine, September 1944; H.R. Greenapple, ed.,D.C. Stephenson, Irvington 0492: The Demise of the Grand Dragon of the Indiana Ku Klux Klan (Plainfield, IN: SGS Publications, 1989); and Grand Dragon: D.C. Stephenson and the Ku Klux Klan in Indiana (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1991), accessed Google Books .

Stephenson was sentenced to life imprisonment in November 1925. According to articles in the Times in September and October 1926, after waiting a year for a pardon and not receiving one, he smuggled a letter out of his cell stating that he had information showing graft in public offices. This letter reached Vincennes editor Thomas Adams, head of a probe committee of the Indiana Republican Editorial Association, which had been investigating Stephenson's past political activities. In a September 28, 1926 article, the Times described how Adams and the committee had come into possession of documents that "show[ed] conclusively that Stephenson's word was law in Indiana, that he manipulated appointments and forced courts to do his bidding under threat of political destruction." Determined to help uncover the truth and encourage further investigations, both the Times and Adams tried to interview Stephenson, but were refused permission by Governor Jackson. In a letter to Senator James E. Watson, Senator Arthur Robinson, and Honorable Clyde Walb, published in the Times on October 5, 1926, Boyd Gurley, editor of the paper, wrote that "The Times demands that you gentlemen at once use your influence with Governor Ed Jackson to permit thorough probe of the grave charges made by Thomas Adams . . ." On October 19, 1926, the paper published a transcript of Stephenson's letter, in which he alluded to information he had regarding the 1924 election, including how votes had been bought, political decisions swayed, and how he had helped finance Jackson's campaign.

The investigations continued through the following year. In a May 1927 article, the Times wrote "Governor Jackson declares that he holds no money, property, or credits of Stephenson's and is in no way indebted to him." A June 29, 1927 article quoted Stephenson, through his attorney Robert Moore, who stated "I have been double-crossed for the last time and I am ready to talk [with Prosecutor William Remy]." Stephenson was finally allowed to talk to the newspapers on July 1, 1927, and on July 7, the Times wrote that Marion County prosecutors had begun a new search for documents which Stephenson claimed would highlight the political corruption that plagued the state. On July 11, 1927, the Times reported that it had custody of the papers and that it "produced witnesses before the grand jury, who testified that at one time Stephenson had [the] documents in his possession." The Times began printing exact copies of these documents that day, beginning with a check from Stephenson to Jackson before the latter became governor.

For the remainder of July and August, the Times filled its pages with reprints of letters and checks from Stephenson's papers detailing how much money had been spent to help get Jackson elected. As political corruption was exposed, Jackson became more defensive with regard to his involvement with Stephenson and stated that any money he obtained had been for reasons outside of his political campaign for governor. Additionally, he denied charges that he had offered former Governor Warren McCray $10,000 to influence his appointment for prosecuting attorney in 1923. Reports of corruption went beyond the Governor. On July 21, the Times revealed that Indianapolis Mayor John Duvall had also reportedly sought Stephenson's aid when he was a candidate for Republican nomination for mayor in 1924. The Times wrote on July 27, 1927, that it had turned over Stephenson's documents to the Marion County grand jury for examination and stated that ". . . the people are entitled to know what happened to their government and to their elections. They are entitled to have the name of the State be redeemed . . . they are entitled to know who besmirched the State if the charges are true."

According to a May 1928 Times article summarizing the paper's crusade, Mayor Duval was eventually convicted of violation of the corrupt practices act and forced to resign; six of the city councilmen were indicted for accepting bribes and had pleaded guilty and resigned; and "the city administration of Indianapolis, heir to the days of Stephenson, a product of his Klan control, was completely changed and a new council elected." Governor Jackson, who was indicted for conspiracy to bribe Governor McCray, was acquitted because the statute of limitations had lapsed.

[7] "The Pulitzer Prizes: Public Service," Pulitzer.org; "Pulitzer Prize for 1928 is Awarded to the Times," Indianapolis Times, May 8, 1928, 1; "Knowledge That It Has Served the Public is Real Reward of Times, Indianapolis Times, May 8, 1928, 1; George B. Parker, "The Pulitzer Award," Indianapolis Times, May 8, 1928, 4; Roy Howard, "Congratulations," Indianapolis Times, May 8, 1928; "The Pulitzer Prize in Journalism is Awarded to the Indianapolis Times;" Logansport Pharos Tribune, May 15, 1928, 3; "Striking Thoughts," Valparaiso Vidette-Messenger, May 15, 1928, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com.

The Times won the Pulitzer Prize for Public Service in Journalism in 1928 "for its work in exposing political corruption in Indiana, prosecuting the guilty and bringing about a more wholesome state of affairs in civil government." A May 1928 Valparaiso Vidette-Messenger article called the Times the "conspicuous champion" of the independent press and stated that its work to combat the KKK and corruption in state government represented "the new spirit of public service that [was] moving the newspapers of the nation to new ideals."

[8] "Clothe a School Child for Christmas," Indianapolis Times, December 1, 1930, 1; "Hundreds of Children Need Help! Clothe a School Child for Christmas," Indianapolis Times, December 3, 1930, 1; "422 Children Get Clothing in Yule Drive," Indianapolis Times, December 26, 1930, 1; "Clothe a Child Letter Typical of Good Done," Indianapolis Times, December 26, 1931, 2; "$10,000 Spent to Clothe 806 Needy Children in City," Indianapolis Times, December 25, 1933, 1; No Title, Indianapolis Times, December 12, 1939, 13; "Big-Hearted City Gives $86,858 for Record Times Clothe-A-Child," Indianapolis Times, December 26, 1951, 1; "3 Newspaper Yule Funds Total $154,006," Indianapolis Times, December 26, 1952, 1; "Times' Plan Adopted in Michigan," Indianapolis Times, December 23, 1952, 1; "The Times Clothe-A-Child Marks Its 25th Anniversary," Indianapolis Times, November 21, 1954, 1; "Times Clothe-A-Child Joins United Front," Indianapolis Times, September 15, 1957, 1.

During the winter of 1930, in the midst of the Great Depression, the Times began an annual campaign to help provide clothing for Indianapolis' disadvantaged children. On December 1, 1930, the Times wrote that "hundreds of children in the city today are unable to attend school regularly because of lack of suitable, warm clothing." As a result of these conditions, the paper stated that it "makes this plea to all Indianapolis citizens and groups of citizens fortunate enough in these days of depression to be able financially to share with others and aid them in their hour of dire need." The Times ran articles throughout the month, encouraging individuals to help. By 1933, it reported that Mile of Dimes had joined the annual campaign and asked individuals to lay down their spare dimes on the sidewalk in front of stores on Washington St. This money was then collected to purchase additional clothing for children. The Clothe-A-Child campaign continued to grow throughout the years. A 1952 Times article reported that it raised $103,032.78 that year alone. By 1954 it celebrated its 25th anniversary and three years later, in 1957, it joined the United Fund of Greater Indianapolis.

[9] Irving Leibowitz, "Hospitals Used as Hot Issue," Indianapolis Times, January 26, 1953, 3; Irving Simpson, "Community Chest Contributors Hear Author of 'The Snake Pit,'" Kokomo Tribune, January 27, 1954, 10, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Irving Leibowitz, "Progress or Decay for Indiana," Indianapolis Times, November 14, 1954, 33; John V. Wilson, "Speedup in Handling Mental Cases Urged," Indianapolis Times, November 9, 1954, 5; "The Times Wins Top Award for Mental Health," Indianapolis Times, November 28, 1954, 1; "Mental Health Award Presented to Times, Logansport Pharos Tribune, November 29, 1954, 2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Times Crusade Wins Mental Health Award," Indianapolis Times, January 29, 1955, 2; "Times Wins Top Award for Crusade," Indianapolis Times, May 9, 1955, 1; "Indianapolis Paper Will Get Award," Holland Evening Sentinel (Holland, MI), May 9, 1955, 9, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Cited for Series of Stories in '58," Logansport Pharos Tribune, May 13, 1959, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "The Times Crusaded for the Public," Indianapolis Times, October 11, 1965, 1; John A. Talbott, "1950: The Beginning of a New Era in Mental Health," Psychiatric Services (January 2000): 7.

In the early 1950s, the Times published articles advocating for better care of the mentally ill. In a January 1953 piece, the paper commented on the poor conditions of Indiana's mental hospitals, describing problems with overcrowding and hospital mismanagement. In a November 1954 article, it wrote that "mental illness is a sickness that should carry no stigma of shame" and that "the state - representing society - takes on as an obligation to the patients, their relatives and also to the public the job of caring for the mentally ill." According to articles in the Indianapolis Times and the Logansport Pharos Tribune in November 1954, that month, the Indiana Association of Mental Health honored the Times with the first Indiana Mental Health Bell Award for "'outstanding service' in encouraging mental health reforms." In 1955, the paper was further honored by winning the national Mental Health Bell Award. A May 1955 article stated that theTimes had "undertaken not only to report the developments in the field of mental illness…but also to champion the cause of the mentally sick, drawing public attention to their plight and stimulating public action on their behalf."

[10] James R. Hetherington, "The Times Will List 1400 Available Jobs to Speed Recovery," Indianapolis Times, April 8, 1961, 1; James R. Hetherington, "1400 Jobs Listed in the Times Today," Indianapolis Times, April 9, 1961, 1; "Jobs, Jobs, Jobs - Open Now," Indianapolis Times, April 9, 1961, 18-19; James R. Hetherington, "Jobless Swamp Employment Office," Indianapolis Times, April 10, 1961, 1; James R. Hetherington, "Times Job Listing Plan is Spreading," Indianapolis Times, April 11, 1961, 1; James R. Hetherington, "The Times to List 300 New Jobs," Indianapolis Times, April 15, 1961, 1; Dan Kidney, "Goldberg Cites theTimes for Helping Jobless," Indianapolis Times, April 22, 1961, 1; Dan Kidney, "Times Editor to Get Employment Group's 1 st Award for Job Campaign," Indianapolis Times, July 5, 1961, 1; Edson L. Bridges, "A Year End Review of the 1961 Economy," Financial Analysts Journal (November - December 1961): 9-14; "The Times Crusaded for the Public," Indianapolis Times, October 11, 1965, 1.

In order to help combat rising unemployment in the country and spur economic recovery during the short-lived economic recession of 1960-1961, the Times worked to identify job openings in Indiana for its fellow Hoosiers. In the spring of 1961, it began publishing job ads at no charge. According to an April 8, 1961 article, Times editor, Richard D. Peters, stated that "if we can help any unemployed Hoosiers find work, even temporary work, our time and effort will be more than justified." Articles in the April 9, 1961 issue of the Times listed over 1,400 jobs and the April 15 issue identified another 300 jobs. On April 11, James Hetherington reported that "so successful was the Times program…it will be tried in other cities in Indiana and across the nation to help beat the recession." As a result of the paper's work, the International Association of Personnel in Employment Security (IAPES) honored Peters with a certificate of award "in recognition of outstanding achievement and meritorious public service in developing and publishing job opportunities for unemployed workers and his unselfish co-operation with the employment security agency."

[11] Irving Leibowitz and John V. Wilson, "Land-Purchasing Scandal Bared in State Road Department," Indianapolis Times, April 11, 1957, 1; Ted Knap, "$23,300 Profit Told in Two Property Deals," Indianapolis Times, April 11, 1957, 1; "State Investigates Right-of-Way Buying,"Logansport Pharos Tribune, April 11, 1957, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Tinder Taking Land Scandal Evidence to Grand Jury,"Indianapolis Times, April 12, 1957, 1; "Gore Wants U.S. Spotlight on State Highway Scandal," Indianapolis Times, April 14, 1957, 1; "Gov. Handley Extends State Investigation," Logansport Pharos Tribune, April 16, 1957, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Sen. Gore Praises Work of the Times," Indianapolis Times, April 23, 1957; "No Federal Funds in Indiana Scandal," New York Times, May 8, 1957, 22, accessed ProQuest; "Report of Grand Jury," Indianapolis Times, June 27, 1957, 19; "Times Wins National Award for Exposing Highway Scandal," Indianapolis Times, June 28, 1957, 1; Prison Terms Seen in Highway Scandals," Indianapolis Times, June 28, 1957, 1; "2 in Roads Case Guilty in Indiana," New York Times, November 3, 1957, 54, accessed ProQuest.

On April 11, 1957, the Times uncovered irregular land-buying deals on Madison Avenue in Indianapolis, in which middlemen made over $23,000 in profits in the mid-1950s on the sale of lots for a state expressway. According to articles that day, Indianapolis residents were paid a total of $2,500 for lots that were later sold to the state for $25,800. The Times reported that it had been investigating the property sales for several years and it also questioned land-buying deals in Evansville, Gary, Richmond, and South Bend. Because of the paper's work, Governor Handley ordered investigations into Indiana's state highway department and other state departments to expose any wrongdoings.

Prosecutor John Tinder took the lead in the case in Indiana, stating in an April 12, 1957 Times article that he met with the chairman and commissioners from the State Highway Commission after hearing the Times' news and commended the paper for exposing the irregularities. By April 14, 1957, the case reached the federal level and the Times reported that Albert Gore, Sr., Chairman of the Senate Public Works Highway Subcommittee, intended to put a "national spotlight" on the highway scandal. Gore praised the Times in an April 23 article, stating that "the fine work of the Times reporters in bringing to the public the misapplication of highways funds is another typical example of how a newspaper serves the community." By June 28, 1957, the Times reported that the Marion County Grand Jury had indicted five men involved in the scandals on counts of bribery and conspiracy to embezzle funds, including former State Highway Chairman Virgil W. Smith. The Times won Scripps-Howard's national "story-of-the-month" award for uncovering the corruption.

[12] "Streets of Fear," Indianapolis Times, March 11, 1962, 6; Ted Knap, "Crimes Against People Soar in City," Indianapolis Times, March 12, 1962, 1; Ted Knap, "Death in a Purse Grab is Not Listed as a Crime," March 14, 1962, 1; Ted Knap, "Police 'Clear' Many Crimes Not Solved," Indianapolis Times, March 15, 1962, 1; Walter Spencer, "Mayor Tells Police: Count All Crimes," March 15, 1962, 1; Ted Knap, "Fewer Policemen on Streets Here Than 10 Years Ago," Indianapolis Times, March 16, 1962, 1; "Police Are Examining Crime County System,"Indianapolis Times, March 17, 1962, 1; "Civic Leaders Express Concern, Worry, Fear; Urge Immediate Action to Reduce City Crime," Indianapolis Times, March 18, 1962, 1; "Just a Beginning," Indianapolis Times, March 19, 1962, 10; "Opportunity for Mayor Boswell," Indianapolis Times, March 30, 1962, 16; "Mayor Maps Plan to Get Desk Cops Back on Streets," Indianapolis Times, March 30, 1962.

In March 1962, the Times ran a series of articles entitled "Streets of Fear," in which it alerted the Indianapolis community to rising crime rates in the city and a distortion in how and what crimes were being reported. According to a March 14, 1962 article, the Indianapolis Police Department had been classifying unsolved crimes as "investigations" and, in turn, considered them "non-crimes." On March 15, the Times stated that "police accounting methods can give the appearance of trimming crime - but only on paper." Further, the newspaper reported on March 19 that the city was using fewer men and resources than it had been ten years earlier and cited the need for more policemen on the streets, rather than at desk jobs. The Times promised to "continue to dig and continue to report" and to "support with vigor every community effort to erase fear from what should be streets of good neighbors." As a result of the paper's work, Mayor Charles Boswell ordered police to overhaul the city's crime reporting system and began work to get policemen back to active police duties. According to a March 30, 1962 article, Boswell said the Times articles "assisted materially in guiding the city administration to this action" and that he hoped the added strength for the police department would help make the streets safer.

[13] Tom Boardman and George Horton, letter to All Employees, October 11, 1965, Frank N. Widner Papers, 1939-2003, Manuscript and Visual Collections Dept., Indiana Historical Society, M1001, Box 1, Folder 1; "'Regretfully. . .And Reluctantly,'" Indianapolis Times, October 11, 1965, 1; "The Times Suspends Publication Today," Indianapolis Times, October 11, 1965, 1; "The Times Stops Publication After 77 Years," Indianapolis News, October 11, 1965, Newspaper Clippings File, "Indianapolis Newspapers, 1960-69," Indiana State Library; "We've Lost a Member of Family," Indianapolis News, October 12, 1965, Newspaper Clippings File, "Indianapolis Newspapers, 1960-69," Indiana State Library; "Final Indianapolis Times Issue Monday," Greensburg Daily News (Greensburg, IN), October 12, 1965, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Times, 77 Years Old, Quits Publication," Indianapolis Star, October 12, 1965, Newspaper Clippings File, "Indianapolis Newspapers, 1960-69," Indiana State Library; Rex Redifer, "Defunct Paper's Staffers Will Recall Old Times," Indianapolis Star, 1990, Frank N. Widner Papers, 1939-2003, Manuscript and Visual Collections Dept., Indiana Historical Society, M1001, Box 1, Folder 5.

The Indianapolis Times ceased publication on October 11, 1965. Tom Boardman (editor) and George Horton (business manager) sent a letter to all 420 employees that day, stating that "due to the permanent suspension of the Indianapolis Times, the services of all employees are terminated." According to the letter, staff members were guaranteed no less than two weeks' termination pay and a clearinghouse was created to help them secure other employment. Many moved on to join the staffs of other Indianapolis newspapers. Times articles reported that "the decision to suspend publication was made only because economic facts offer no alternative." The Greensburg Daily News referred to the demise of the Times as "a loss to Indiana." The Indianapolis News, quoting Governor Roger Branigin on October 11, called the closing, "a serious blow to the community."

See the Frank N. Widner Papers at the Indiana Historical Society for information on biennial reunions of former Times staff members, their yearly newsletters, and their affinity for the paper.