Location: Near 914 Columbia St., Lafayette, IN 47901 (Tippecanoe County, Indiana)

Installed 2014 Indiana Historical Bureau, Indiana Humanities, and Indiana Supreme Court

ID#: 79.2014.1

Text

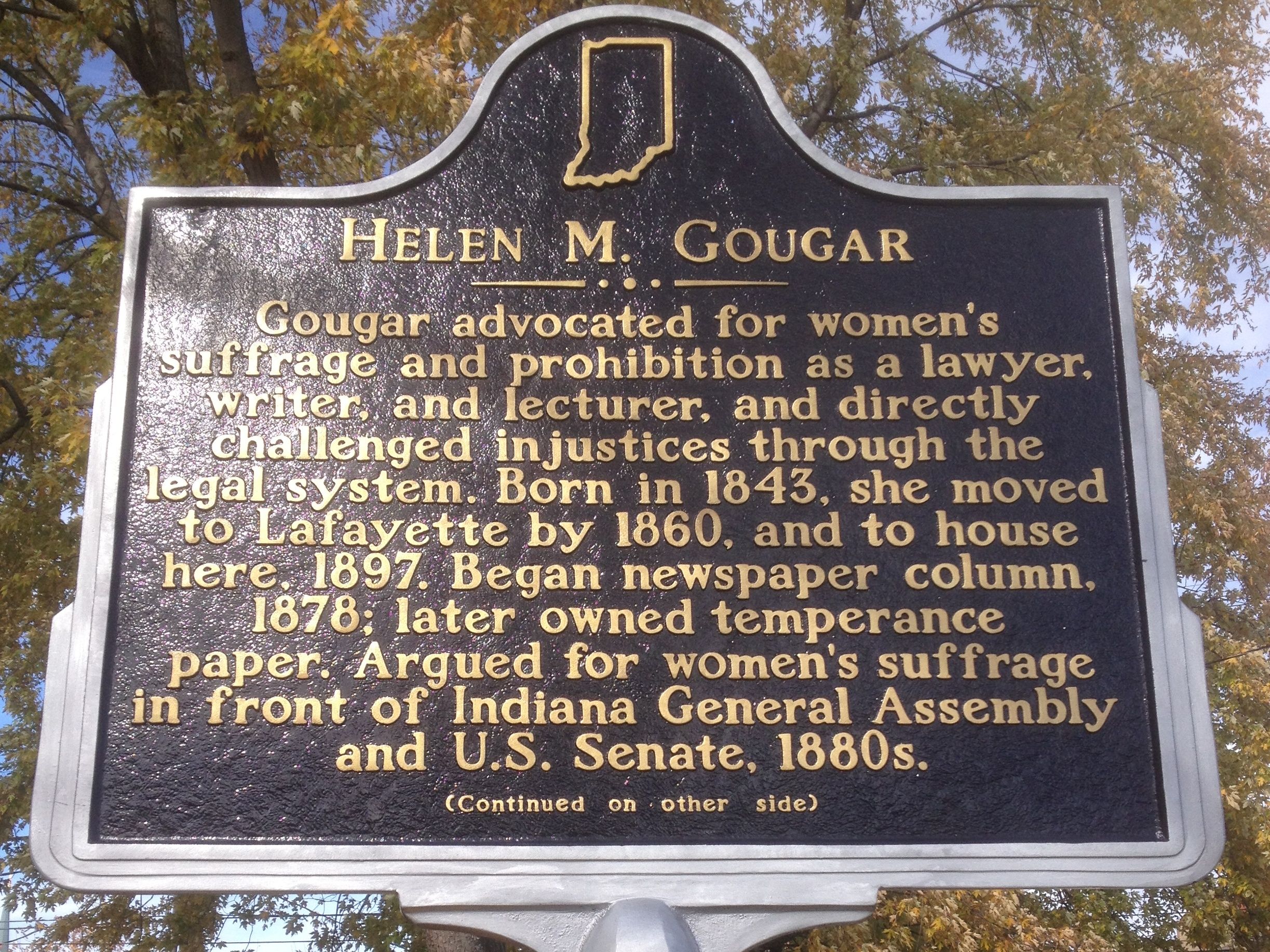

Gougar advocated for women's suffrage and prohibition as a lawyer, writer, and lecturer, and directly challenged injustices through the legal system. Born in 1843, she moved to Lafayette by 1860, and to house here, 1897. Began newspaper column, 1878; later owned temperance paper. Argued for women's suffrage in front of Indiana General Assembly and U.S. Senate, 1880s.

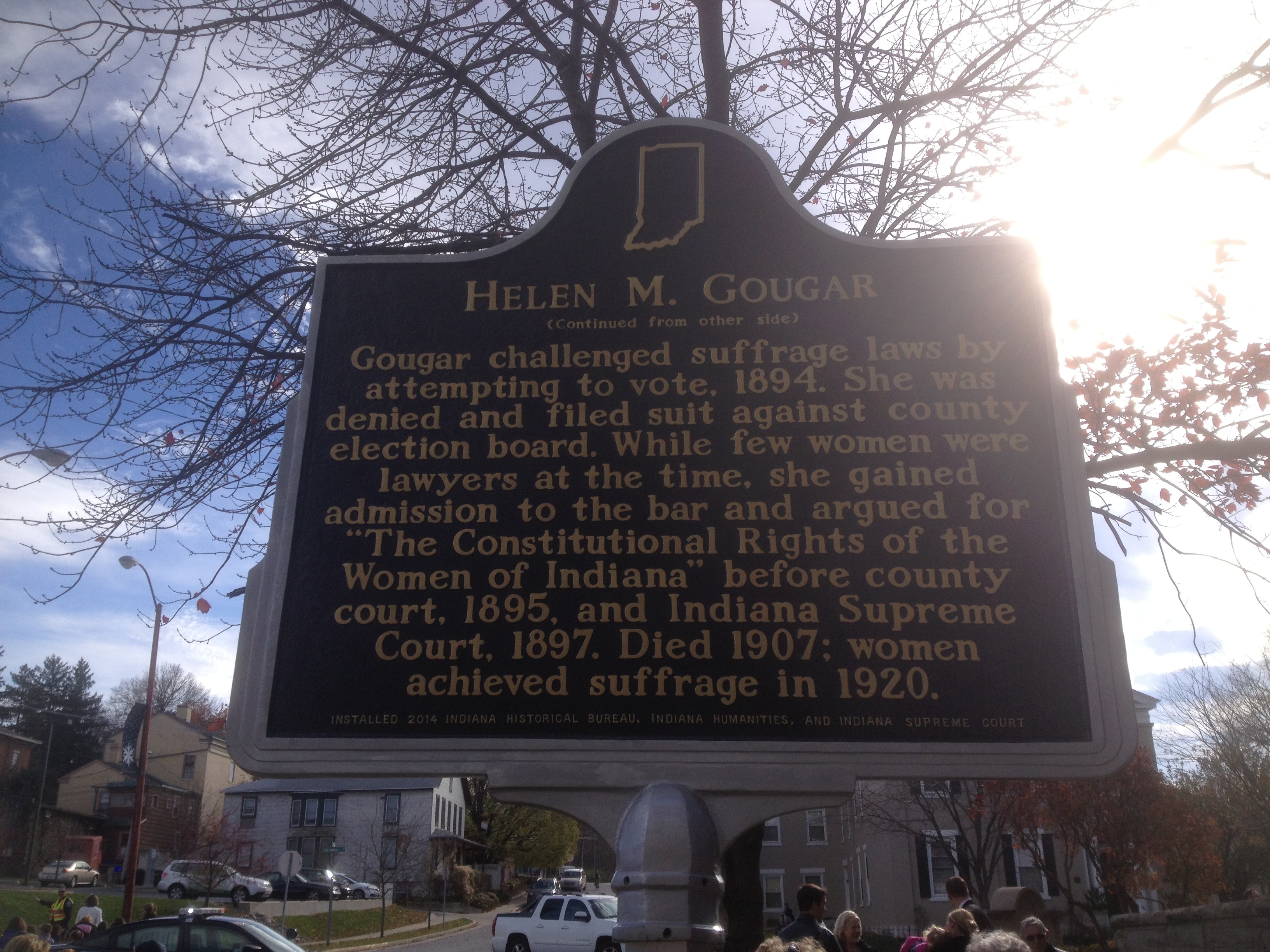

Gougar challenged suffrage laws by attempting to vote, 1894. She was denied and filed suit against county election board. While few women were lawyers at the time, she gained admission to the bar and argued for "The Constitutional Rights of the Women of Indiana" before county court, 1895, and Indiana Supreme Court, 1897. Died 1907; women achieved suffrage in 1920.

Annotated Text

Side One

Gougar advocated for women’s suffrage and prohibition[1] as a writer, lecturer, and lawyer,[2] and directly challenged injustices through the legal system.[3] Born 1843,[4] she moved to Lafayette by 1860,[5] and to house here, 1897.[6] Worked as newspaper columnist, starting 1878,[7] and editor, 1881.[8] Argued for women’s suffrage in front of Indiana General Assembly[9] and U.S. Senate, 1880s.[10]

Side Two

Gougar challenged suffrage laws by attempting to vote, 1894.[11] She was denied and filed suit against Tippecanoe County Election Board.[12] After admission to the bar,[13] she argued for “The Constitutional Rights of the Women of Indiana” before county court, 1895,[14] and Indiana Supreme Court, 1897.[15] Women did not achieve suffrage until 1920,[16] years after Gougar’s death in 1907.[17]

New York Times accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Lafayette Daily Courier and Our Herald accessed through Indiana Newspaper Collection, Indiana State Library, microfilm; and all other newspaper articles accessed NewspaperArchive.com, unless otherwise noted.

[1] "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, May 3, 1879, 2; "Woman Suffragists," Indianapolis Journal, May 26, 1880, 3; "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, May 29, 1880, 2; "Feminine Franchise," Lafayette Daily Courier, June 17, 1880, accessed Kreibel Research File, Helen Gougar Collection, Tippecanoe County Historical Association; “Gougar-Mandler,” Lafayette Daily Courier, March 8, 1883, 1, 4; Robert C. Kriebel, Where Saints Have Trod: The Life of Helen Gougar (West Lafayette: Purdue University Press, 1985), passim; Rebecca Edwards, Angels in the Machinery: Gender in American Party Politics from the Civil War to the Progressive Era (New York: Oxford Press, 1997), 4-11; Ann D. Gordon, ed., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Volume IV (Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006), xxiii, accessed GoogleBooks;

Like many nineteenth century reform-minded women, Gougar first joined the temperance movement, working for total prohibition of alcohol, and only later transitioned into supporting women’s suffrage (seeing the woman’s vote as the best means of achieving prohibition). Gougar viewed alcohol as the cause of most of society’s problems and the main oppressor of women and families. Gougar explained that "about 1871" she was inspired to begin advocating for temperance and was "a member of a small temperance society." Since 1871, she had been “adding a little, day by day, to her public work." She first thought that “praying away the evil” of alcohol was the solution, but “about a year after she had become a temperance worker,” she “became convinced that the best way was to vote it away." Unlike many suffrage leaders (notably Susan B. Anthony), Gougar never separated temperance issues from her suffrage campaigning. However, she did become convinced of the inherent equity of universal suffrage by the end of the 1870s. In an 1879 Lafayette Daily Courier column, Gougar argued that it was unfair for ambitious, educated, politically-aware women to be denied suffrage while so many men voted by party line and for "the most sociable, good-hearted fellow.” (See footnote 2 for more information on Gougar’s professional roles as journalist and writer advocating for suffrage).

According to historian and professor Ann D. Gordon, 1880 saw a change of pace for National Woman Suffrage Association leaders Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, now in their sixties. These suffrage leaders were encouraging younger woman to take the reigns, and according to Gordon, they succeeded in Helen Gougar who had proved herself perhaps “the movement’s most effective speaker” and “an adept organizer.” That same year, 1880, Gougar rose to prominence within the national suffrage movement. In May, she served as a delegate to the National Woman Suffrage Association convention. In June of that year, she chaired a suffrage meeting in Lafayette that featured nationally known leaders, including Susan B. Anthony. The Lafayette Daily Courier called Gougar’s opening address at the convention “brilliant,” and from this time on Gougar was a sought after professional lecturer on many topics, but mainly suffrage and temperance. (For more information on her career as a lecturer, see footnote 2.)

Like other suffrage leaders, Gougar wrote articles, lectured across the country, and lobbied politicians for women’s suffrage throughout her career. Where Gougar differed from many other suffrage and temperance activists was in her direct participation in the legal and political process to achieve her goals. She was especially influential in the suffrage struggle, and thus this text focuses on suffrage rather than her temperance work. See footnotes 3, 11-15 for more information on her work within legal and political systems. See Kriebel’s full-length biography Where Saints Have Trod for a more complete discussion of her temperance and political work. For an overview of women’s roles in suffrage and reform campaigns during the Progressive Era, visit the National Women’s History Museum website.

[2] "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, January 25, 1879, 2; "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, May 3, 1879, 2; "Feminine Franchise," Lafayette Daily Courier, June 17, 1880, Kreibel Research File, Helen Gougar Collection, Tippecanoe County Historical Association; "The Legislature: The Woman's Suffrage Question Presented to the House," Indianapolis News, February 16, 1881, 4, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; Brevier Legislative Reports: Embracing Short-Hand Sketches of the Journals and Debates of the State of Indiana, Regular and Special Sessions of 1881, vols. 19, 20 (Indianapolis: W. H. Drapier, 1881), 190-193, accessed Indiana Memory; "Woman Suffrage: Notes of Indiana's Representatives in the Recent Convention," Indianapolis Journal, October 28, 1881, 3; "Suffrage Notes," New Castle Mercury, February 25, 1882, 1; "Mrs. Gougar in Iowa," (Lafayette) Our Herald, July 21, 1883, 3; “Gougar-Mandler,” Lafayette Daily Courier, March 8, 1883, 1, 4; “Helen M. Gougar,” Business Card, Folder 76.94.6, Box Correspondence, Helen Gougar Collection, Tippecanoe County Historical Association; Frances E. Willard and Mary A. Livermore, eds., A Woman of the Century: Fourteen Hundred-Seventy Biographical Sketches Accompanied by Portraits of Leading American Women in All Walks of Life (Buffalo, NY: Charles Wells Moulton, 1893), 328-329, accessed GoogleBooks; 1900 United States Census (Schedule 1), Lafayette, Fairfield Township, Tippecanoe County, Indiana, Roll: 405, page 15A, Line: 50, June 12, 1900, accessed Ancestry Library Edition; Clifton J. Phillips, Indiana in Transition: The Emergence of an Industrial Commonwealth, 1880-1920 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau & Indiana Historical Society, 1968) 498-502; Betty Barteau, “Thirty Years of the Journey of Indiana’s Women Judges, 1964-1994,” Indiana Law Review 30:1 (1997): 55-62, accessed courts.in.gov; Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, ed. Women Public Speakers in the United States, 1800-1925: A Bio-Critical Sourcebook (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1993), xi-xxii, 267-278, accessed GoogleBooks; Ann D. Gordon, ed., The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Volume V (Piscataway, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006), 141-2, accessed GoogleBooks; Edwards, Angels in the Machinery, 5.

In 1900, the U.S. census listed Gougar’s profession as “lecturer and lawyer,” a title she had earned through over two decades of activism. Gougar joined the movements for temperance and suffrage that started nation-wide, decades before her birth. American women had actively campaigned for reform since the founding of the country. According to historian Karlyn Kohrs Campbell, the concept of “true womanhood” defined women’s roles as “pure, pious, domestic, and submissive.” The expectation for women to be both more moral and more submissive than men led to a contradiction. Women felt called to act on moral issues such as slavery and temperance, and quickly saw (at least by the 1830s) that the ballot and the courtroom would give them the power to affect change. According to historian Rebecca Edwards, “This ideology of female moral superiority offered a rationale for women’s involvement in a host of reform activities, and it quickly led them into politics.” By the close of the Civil War, women were speaking and writing in support of political candidates and were leading the movements for prohibition and women’s suffrage. Indiana was no exception, and the state produced opinionated and educated female writers and speakers such as Juliet Strauss, Amanda Way, and Virginia Meredith (add links). According to historian Clifton Phillips, “The social reform movements of this era [1880-1920] which provoked the most intense emotional response as well as political controversy in Indiana were those concerned with temperance and woman suffrage.” Like Hoosier women Zerelda Wallace and May Wright Sewall, Gougar joined the fight for suffrage and temperance by speaking across the country on lecture tours and refining her arguments through newspaper columns.

According to Gougar, she began publicly advocating for temperance, “about 1871” and “first commenced her public life with the reading of an essay at the commencement of the [Lafayette] Y.M.C.A.” In 1879, she began writing about the evils of alcohol and advocating women’s suffrage. (See footnotes 7 and 8 for information on Gougar’s work as a newspaper writer and editor.) In 1881, she spoke before the Indiana General Assembly. (See footnote 9 for more information on her speeches to state legislatures). The Indianapolis Journal gave an account of Gougar’s speech at the annual meeting of the American Women's Suffrage Association in Louisville in 1881: “She argued the matter of women’s rights from a logical and forcible standpoint, frequently interspersing her address with a humorous anecdote.” In 1882, she spoke at the National Suffrage Association annual convention in Washington D.C. In 1883, she announced via her newspaper, Our Herald, that she would be delivering forty lectures in forty days. Her business card from this period advertised lectures on “Woman Before the Law,” “Woman Suffrage a National Necessity,” and “Aims and Methods of the Liquor League,” among other topics. Also in 1883, the Lafayette Daily Courier reported that she “delivered about 200 lectures in the last two years, often speaking three times a day.” She continued at this pace for most of her career and upon her death in 1907, the Indianapolis News estimated that she "delivered more than two hundred lectures a year for twenty years." According author and professor E. Claire Jerry’s critical essay in Women Public Speakers in the United States, Gougar “delivered over 4,000 speeches during her career” and was paid “impressive sums for her day.” Gougar was known for speaking without notes, directly addressing her opponents’ views point by point. She was often praised for this reasoned and educated speaking style, which reflected her legal training. In 1888, national suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton described Gougar as "the most effective speaker we have" and "some inspiration to me." An 1893 work edited by nationally recognized suffragists Frances Willard and Mary Livermore, noted: “Her special work in reforms is in legal and political lines, and constitutional law and statistics she quotes with marvelous familiarity when speaking in public.”

When Gougar took to the podium and to the press in the 1880s, she joined an active and growing group of women lecturers and writers from Indiana and across the country. However, when she sued for the right of Indiana women to vote in the 1890s, she stood in front of the Indiana courts with few peers. As Judge Betty Barteau (Indiana Court of Appeals) explained in an Indiana Law Review article, Indiana had no central registry of lawyers in the 1890s. Each circuit court would admit members to the bar as it saw fit, and thus, in some counties women had been practicing law, but it is difficult to determine how many or when they began. However, the first woman admitted to practice law by the Indiana Supreme Court was Attoinette Dakin Leach in 1893, in a case known as In re Leach. Gougar recognized the opportunity to challenge suffrage laws in court and acted immediately. In 1895, Gougar was admitted to the bar by the Tippecanoe County Circuit Court, and in 1897, she was admitted by the Indiana Supreme Court. (See footnotes 11 through 15 for sources on her admission to the bar and more information on how she used her legal training to argue for women’s suffrage.)

By the close of the nineteenth century, Gougar had shifted her focus and her lecture topics to political questions, and she campaigned for candidates of various parties which offered the most hope for her temperance and suffrage goals. Because of her years of temperance and suffrage activism, experience in political campaigning, and familiarity with the law, the National Prohibition Party of Indiana nominated Gougar for Attorney General of the state in 1896. While the campaign was not successful, the nomination alone was a testament to her professional abilities and experience. In 1900, she actively campaigned for William Jennings Bryan’s presidential run, accompanying him on the campaign trail and speaking in support of his policy. He showed his appreciation for her efforts in a November 11, 1900 letter consoling her after their defeat.

[3]Western Union Telegraph Co. v. Gougar, 84 Ind. 176, 1882 WL 6313 Ind., May Term 1882 (no. 9486); "Woman's Rights and Wrongs," New Albany Daily Ledger Standard, January 29, 1881, 1; "A Star City Sensation: A Scandal Implicating Mrs. Gougar and Dewitt C. Wallace," Indianapolis Journal, November 29, 1882, 1; "An Indianapolis Sensation: A Female Temperance Advocate Charged with Immorality -- A Suit for Libel," New York Times, November 29, 1882, 1; "The Lafayette Scandal: Extraordinary Interest Manifested in the Case of Mrs. Gougar," New York Times, February 4, 1883, 7; “Gougar-Mandler”, Lafayette Daily Courier, March 8, 1883, 1, 4; "A Verdict for Mrs. Gougar: The Jury Awards Damages in $5,000 against Mr. Mandler," New York Times, April 12, 1883, 1; "Mrs. Gougar's Record: Morse's Charge Still Lacks Substantiation," New York Times, October 15, 1892, 3; "Congressman Morse Sued for Libel," New York Times, October 29, 1892, 6; "Mrs. Gougar's Libel Suits Entered," Boston Daily Globe, May 16, 1893, 9; "Not Responsive: Mrs. Gougar's Answers are not Satisfactory," Boston Daily Globe, August 16, 1894, 1; "Morse Poses," Boston Daily Globe, September 13, 1894, 1; "No Damages for Mrs. Gougar," New York Times, September 15, 1894, 8; Gougar v. Morse, 66 F. 702, C.C.D. Mass., March 21, 1895 (No. 250); Willard and Livermore, eds., A Woman of the Century, 328-329.

Gougar first used the legal system to fight injustice toward women in a suit filed against Western Union in 1881. She sued the company for delivering the “more important” telegraphs sent by men before those sent by women (regardless of order received). Gougar also brought lawsuits against those who sought to damage her reputation -- and thus discredit her advocacy of suffrage and temperance causes. She was attacked viciously in the press by those who opposed her views on politics and reform. For example, her slander suit against Lafayette Police Chief Harry Mandler (starting in 1882) made national headlines. Mandler, an influential Lafayette Democrat, alleged that Gougar was having a romantic affair with Captain De Witt Wallace who was running as a Republican for the Indiana Senate and who was a well-known supporter of temperance and women’s suffrage (policies contrary to the views of the local Democratic Party). Gougar sued Mandler, charging that his slanderous attack was intended to discredit Wallace as a political opponent and her as a leading suffrage and temperance advocate. The trial was covered in detail by Indiana and national newspapers, and thus Gougar was fighting for her reputation also in the court of public opinion. The New York Times noted, "Mrs. Gougar is the publisher of a weekly temperance and suffrage paper, Our Herald, and by her sharp pen has surrounded herself with bitter enemies." The Times also stated that the case had "taken on a phase of temperance and suffrage versus the liquor interest." She not only won the suit in 1883 (after ten hours of cross-examination), but also proved that outspoken women could not be shamed into silence. That year, Frances E. Willard and Mary A. Livermore described Gougar’s “battle” against those who sought “to weaken her power, in political circles, by defamation.” The description continued, “In this battle she decided forever the right of women to take an active part in political warfare without being compelled to endure defamation.” Most notably, Gougar challenged Indiana suffrage laws by attempting to vote in 1894 municipal elections. When denied she sued the election board. (See footnotes 11 through 15 for more information on the case.)

[4] 1850 United States Federal Census (Schedule 1), Eckford, Calhoun County, Michigan, Roll M432_348, page 206B, Line 28, October 8, 1850, accessed Ancestry Library Edition; 1860 United States Federal Census (Schedule 1), Lafayette, Tippecanoe County, Indiana, Roll M653_300, page 858, Line 31, June 18, 1860, accessed Ancestry Library Edition; “Helen M. Gougar,” August 16, 1886, microfilm: M237, Roll: 497, Line: 19, List: 979, New York Passenger Lists, 1820-1957, accessed Ancestry Library Edition; “John D. Gougar,” December 10, 1863, Index, Michigan Marriages, 1851-1875, accessed Ancestry Library Edition; Photograph of Grave, "Helen M. Gougar," Spring Vale Cemetery, Lafayette, accessed Find-A-Grave.

Helen Jackson was born July 18, 1843 in Michigan. She married John Gougar in 1863.

[5] 1860 United States Federal Census; “Gougar-Mandler,” Lafayette Daily Courier, March 8, 1883, 1, 4.

During the 1883 Mandler trial, Gougar testified that she "came to Lafayette in May, 1860, and entered the public schools as a teacher" and taught for four years. The 1860 census confirms her recollection.

[6] R.L. Polk & Co.'s Lafayette Directory, 1896-97 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk and Co., 1896) 134, U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed Ancestry Library Edition; R.L. Polk & Co.'s Lafayette Directory, 1898-1899 (Lafayette: Press of the Morning Journal, 1898), accessed Tippecanoe County Historical Association; Lafayette Morning Journal, March 11, 1897, Kriebel Research File, Folder 82.195.4, Helen Gougar Collection, accessed Tippecanoe County Historical Association; “John D. Gougar: His Beautiful Home on East Columbia Street,” (Indianapolis) Indiana Woman, December 11, 1897, Kriebel Research File, Folder 82.195.4, Helen Gougar Collection, accessed Tippecanoe County Historical Association; “Lafayette Issue: The Indiana Woman Devotes Saturday’s Issue to Our City – Its People and Its Resources,” Lafayette Morning Journal, December 13, 1897, Kriebel Research File, Folder 82.195.4, Helen Gougar Collection, accessed Tippecanoe County Historical Association; "I.D.E.A.," Columbus Daily Times, May 31, 1898, 4; New Albany Public Press, June 1, 1898, 1; 1900 United States Census; 1905 Lafayette City Directory, U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed Ancestry Library Edition.

The Gougars resided at 194 Columbia Street according to the 1896 city directory. According to the Lafayette Morning Journal, they began building a new home, they called Cottage Castle, at 914 Columbia Street in March of 1897. The home was completed by December 1897, according to the Indiana Woman, a weekly magazine, which described the finished home. The 1898 city directory confirms their move to the corner of 10th and Columbia Streets. As of 2014, the Fisher-Loy Funeral Chapel occupies the residence.

[7] "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, November 2, 1878, 1; "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, November 9, 1878, 2; "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, November 15, 1878, 2; “Bric-a-Brac,” Lafayette Daily Courier, January 4, 1879, 2; "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, January 25, 1879, 2; "Bric-a-Brac," Lafayette Daily Courier, May 3, 1879, 2; “Bric-a-Brac,” Lafayette Daily Courier, August 7, 1880, 2; “Bric-a-Brac,” Lafayette Daily Courier, September 18, 1880, 2.

In November 1878, Gougar began writing a weekly column for the Lafayette Daily Courier under the heading, “Bric-a-Brac: Literature, Science, Art and Topics of the Day.” She often wrote on social sciences and temperance. By 1879, she wrote about women’s suffrage. The last “Bric-a-Brac” ran in September 1880.

[8] "To Our Readers," Our Herald, August 13, 1881, 1; "The Lafayette Scandal: Extraordinary Interest Manifested in the Case of Mrs. Gougar," New York Times, February 4, 1883, 7; Fort Wayne Daily Sentinel, February 19, 1883, 3; "To the Patrons of Our Herald," Our Herald, August 11, 1883, 1; "Mrs. Gougar Bids Good-bye to Our Herald," Our Herald, January 3, 1885, 1; “Helen M. Gougar,” Business Card, Folder 76.94.6, Box Correspondence, Helen Gougar Collection, Tippecanoe County Historical Association.

Gougar became editor of Lafayette paper, Our Herald, in 1881. In her introduction as editor, Gougar said that the paper would be an advocate of temperance and women’s suffrage. She wrote:

We shall aim to present facts and arguments from time to time that will tend to remove undue prejudice, and educate both men and women to see the justice and necessity of making the women of our State citizens with full rights and privileges to protect themselves and distribute their taxes by the use of the elective franchise.

In February 1883, the New York Times referred to her as the “publisher” of Our Herald. That same month, the Fort Wayne Daily Sentinel referred to Gougar as the publisher and her brother-in-law as “business manager.” In August 1883, Gougar announced that Our Herald would be published monthly instead of weekly. On her business card, which lists Our Herald as a monthly paper, Gougar referred to herself as “editor and proprietor.” Further research is needed to determine exactly when she became owner of the paper. Gougar sold Our Herald’s assets in 1885.

[9] Brevier Legislative Reports: Embracing Short-Hand Sketches of the Journals and Debates of the State of Indiana, Regular and Special Sessions of 1881, vols. 19, 20 (Indianapolis: W. H. Drapier, 1881), 190-193, accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collections; "The Legislature: The Woman's Suffrage Question Presented to the House," Indianapolis News, February 16, 1881, 4, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; "The Legislature: The Suffrage Question Argued before the Senate," Indianapolis News, February 17, 1881, 2, 4, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “The Legislature:"The Legislature: The Proceedings in Both Branches Yesterday," Logansport Evening Pharos, February 18, 1881, 1; "The History of the So-called Woman Suffrage Presidential Electoral Bill," (Chicago) Daily Inter-Ocean, April 9, 1881, 10, accessed 19th Century U.S. Newspapers, Gale Digital Collections; House Journal, Proceedings of the House of Representatives of the State of Kansas, Fifth Biennial Session, Begun at Topeka, January 11, 1887 (Topeka, Kansas: Kansas Publishing House, 1887), 503, accessed GoogleBooks; "American Notes," The (Brisbane, Queensland, Australia) Queenslander, May 11, 1889, 883, accessed National Library of Australia; Journal of the House of Representatives of the Thirty-Seventh General Assembly of the State of Illinois (Springfield: H W. Rokker State Printer and Binder, 1891), 1417, accessed Google Books; Journal of the Indiana State Senate during the Fifty-Seventh Session of the General Assembly, Commencing Thursday, January 8, 1891 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1891) 584, 600-603, accessed GoogleBooks; "What May Be When Women Vote: Disgraceful Scene in a Kansas Town," Hamilton (Ohio) Daily Democrat, April 11, 1887, 3; "Woman Suffrage in Kansas," Daily Inter Ocean, April 12, 1887, 4, accessed 19th Century U.S. Newspapers, Gale Digital Collections; Willard and Livermore, eds., A Woman of the Century, 328-329; Ida Harper, ed. “Three Women,” Locomotive Firemen’s Magazine 11: 7 (July, 1887): 402, accessed GoogleBooks; “Mrs. Helen Gougar,” brochure, circa 1905, Traveling Culture: Circuit Chautauqua in the Twentieth Century Digital Collection, accessed University of Iowa libraries.

In February 1881, Gougar first argued for women’s suffrage in front of the Indiana General Assembly. While she spoke before both the House and the Senate, the 1881 Brevier Legislative Reports quoted her speech before the House at length:

We are here by the invitation and appointment of educated, thinking, cultured and patriotic men and women – women engaged in the different professions, trades, arts, sciences and literature, who are demanding increased powers – that the ballot may be given to them, that they may use it on behalf of justice and virtue.

She appeared in front of state legislatures many times and in several states over her career, speaking for both temperance and suffrage. For example, in 1891, she spoke in support of municipal suffrage in front of the Illinois House of Representatives, and on municipal suffrage and prohibition again before the Indiana General Assembly. The Indiana State Senate Journal described the proceedings of February 19, 1891, noting that Gougar “delivered an eloquent and earnest address on prohibition, municipal suffrage, and other social and political reforms, making a strong appeal to the Senate for the enactment of laws on these subjects.” A brochure for a speaking engagement in Iowa circa 1905 provided the audience members with quotes about and taken from her speeches before the New York General Assembly, the Wisconsin House of Representatives, the Kansas General Assembly, the Indiana Senate, and the Iowa General Assembly.

Gougar also drafted legislation granting women the right to vote in municipal elections in Kansas. The Kansas General Assembly passed the bill in 1887. Prominent suffragist Ida Harper described Gougar’s “brilliant leadership in the memorable suffrage campaign just closed in Kansas.” A Woman of the Century noted, “Mrs. Gougar is the author of the law granting municipal suffrage to the women of Kansas, and the adoption of the measure was largely due to her efforts.”

[10] "Remarks by Mrs. Helen M. Gougar," Debate on Woman Suffrage in the Senate of the United States, 49th Congress, Second Session, December 8, 1886, and January 23, 1887 (Washington, 1887), 61-64, accessed Project Gutenberg, Ebook # 11114.

In 1886, Gougar spoke in favor of women’s suffrage in front of the United States Senate. Her speech stated in part:

Gentlemen, we are here on behalf of the women citizens of this Republic, asking for political freedom. I maintain that there is no political question paramount to that of woman suffrage before the people of America to-day. . . So I come to ask you, as representative men, making laws to govern the women the same as the men of this country (and there is not a law that you make in the United States Congress in which woman has not an equal interest with man), to take the word "male" out of the constitutions of the United States and the several States, as you have taken the word "white" out, and give to us women a voice in the laws under which we live.

[11] In re Leach, 134 Ind. 666, 34 N.E. 641, Ind. 1893, June 14, 1893; Helen Gougar, "Important Decision in Indiana," (Boston) Woman's Journal, July 15, 1893, 224, accessed via microfilm, History of Women Collection, Indiana University Libraries; "Mrs. Gougar Will Insist on Voting," New York Times, July 24, 1893, 1; “Mrs. Gougar Raises A Row,” Chicago Daily Tribune, October 10, 1894, 10, accessed IU Digital Collections, Indiana University Libraries; "Helen M. Gougar Attempts to Vote," Chicago Daily Tribune, November 7, 1894, 3, accessed IU Digital Collections, Indiana University Libraries; "Helen Gougar Was Not Allowed to Vote at Lafayette," Fort Wayne Sentinel, November 8, 1894, 1; Indiana Law Review 30:1 (1997): 55-62; "Indiana Women Try To Vote," (Boston) Woman's Journal, December 1, 1894, 382-383, accessed via microfilm, History of Women Collection, Indiana University Libraries; Campbell, ed., Women Public Speakers in the United States, xi-xxii, 267-278.

When the Indiana Supreme Court case In re Leach decided definitively that women were not excluded from the bar, Gougar claimed that the timing was right for a suffrage “test case.” In February 1893, Attoinette Dakin Leach applied to the Greene/Sullivan Circuit Court for admission to the bar and was denied. The circuit judge cited Article VII, section 21 of the 1851 Indiana Constitution which reads, “Every person of good moral character, being a voter, shall be entitled to admission to practice law in all courts of justice.” The judge interpreted the wording to mean that women, not being allowed to vote, could not practice law. However, the judge did note that Leach was “of good moral character” and “possesses sufficient knowledge of the law.” Leach appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court and in her appellate brief argued that the term “voter” was meant to expand the class of people eligible to practice law and that the intent of the article was not to exclude women. On June 14, 1893, the Supreme Court decided in her favor, agreeing that the law did not intend to specifically exclude women from admission to the bar.

Gougar immediately saw that In re Leach could serve as precedent for a Supreme Court decision that would grant Indiana women the right to vote. She would argue that the wording of the 1851 Indiana Constitution that gave males the right to vote, did not intend to exclude females. (See footnote 14 for more information). One month after the In re Leach decision, Gougar wrote an article published in the Woman’s Journal, stating, “…in this single Supreme Court decision may rest the key that will unlock the bar to National woman suffrage. I shall arrange a test case for the courts at the earliest election held in the State." The New York Times quoted from her July 23, 1893 speech in that city, “At the next election in my State I shall offer my vote, and if the election officers refuse it I shall carry the question to the Supreme Court. If the recent decision of that body is good law, it must decide in my favor, and then the women of Indiana must be given the full franchise.”

On October 10, 1894, the Chicago Daily Tribune reported that Gougar convinced 300 women to pledge that they would go to the polls in November and attempt to vote. True to their pledge, on November 6, 1894, Helen Gougar arrived at her polling place in Lafayette and demanded a ballot, while large groups of women across Indiana followed her lead. The Woman’s Journal reported, “As a result of the movement initiated by Mrs. Helen Gougar, women went to the polls on election day in Indiana . . .”

[12] Ibid.; "Helen Will Try It," Fort Wayne Sentinel, August 25, 1894, 1; "Mrs. Gougar is Bound to Vote," Chicago Daily Tribune, August 25, 1894, 2, accessed IU Digital Collections, Indiana University Libraries; "Mrs. Gougar's Suit," Fort Wayne News, December 18, 1894, 10; Helen Gougar, Statement of Suit against Tippecanoe County Superior Court, December 28, 1894, Correspondence File, Folder 65.77, Helen Gougar Collection, Tippecanoe County Historical Association.

As expected, Gougar and her supporters were denied the opportunity to vote. The Woman’s Journal reported, “She was permitted to enter the booth and ask for a State, county and township ballot, but was refused on the simple ground of sex.” Gougar then filed suit against the Tippecanoe County Election Board.

[13] "Helen Gougar Was Not Allowed to Vote at Lafayette," Fort Wayne Sentinel, November 8, 1894,1; "Indiana Women Try To Vote," (Boston) Woman's Journal, December 1, 1894, 382-383, accessed via microfilm, History of Women Collection, Indiana University Libraries; "Mrs. Gougar's Suit," Fort Wayne News, December 18, 1894, 10; ; “The Test Vote Case,” Lafayette Morning Journal, January 11, 1895, 1; "Mrs. Gougar's Suit," Fort Wayne Sentinel, January 11, 1895, 1; Goshen Daily News, January 11, 1895, 1; "Helen M Gougar Dead: Temperance Leader Was Member of Indiana Bar and a Political Worker," New York Times, June 7, 1907, 9.

Gougar was admitted to the Tippecanoe County Bar January 10, 1895. (Newspapers reported that she had been studying law for two years.) After taking the oath, she acted as her own attorney in the case against the Tippecanoe County Election Board referred to as Gougar v.Timberlake. See footnote 14 for more information.

[14] Ibid.; In re Leach, 134 Ind. 665, 34 N.E. 641, Ind. 1893, June 14, 1893; Helen Gougar, The Constitutional Rights of the Women of Indiana: An Argument in the Superior Court of Tippecanoe County, Ind., January 10, 1895 (Lafayette: Morning Journal Printers, 1895), 35-36, 45, 57, accessed Purdue e-Archives, Purdue University Library; “The Test Vote Case,” Lafayette Morning Journal, January 11, 1895, 1; “They Cannot Vote,” Lafayette Morning Journal, April 20, 1895; Fort Wayne Sentinel, October 4, 1895, 2; "Testing an Apportionment Act," New York Times, November 1, 1895, 15.

On January 10, 1895, Gougar argued for “The Constitutional Rights of the Women of Indiana” in front of the Tippecanoe County Superior Court. Using the In re Leach decision as precedent (see footnote 11), Gougar challenged suffrage restrictions on the basis that the Indiana Constitution did not specifically prohibit women from voting. She also noted that the Declaration of Independence, Articles of Confederation, U.S. Constitution, and the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments gave the right to vote to all citizens. She argued that while the language of the Indiana Constitution gave the right to vote to males, it did not specifically exclude women. The Lafayette Morning Journal reported that Gougar “spoke for four hours, and made an eloquent appeal for her sex and the ballot” and that the address was “one of the finest efforts of her life.” Closing arguments were made by law partners and brothers Sayler & Sayler who explained to the court that laws can be interpreted liberally and conservatively, arguing for the former in this case. The Tippecanoe County Superior Court ruled against Gougar and women’s suffrage on April 20, 1895; Gougar appealed to the Indiana Supreme Court.

[15] Gougar v. Timberlake, 37 L.R.A. 644, 148 Ind. 38, 46 N.E. 339, 62 Am.St.Rep. 487, Ind., February 24, 1897, accessed in.gov/judiciary; “Test Vote Case Is To Be Argued,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 18, 1897, 10, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Bedford Mail, February 20, 1897, 4; “Mrs. Gougar Argues for Suffrage,” Chicago Daily Tribune, February 20, 1897, 6, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “Fighting for Women,” Indianapolis Sentinel, February 20, 1897, 3, accessed Courts in the Classroom, Indiana Judicial Branch, www.in.gov/judiciary/citc/3298.htm.

On February 19, 1897, Gougar was admitted to the bar of the Indiana Supreme Court, and afterwards argued for women’s suffrage in front of the court for almost two hours. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported that she was:

…admitted to practice in the Supreme Court only a few minutes before her oral argument was made…Her oral argument contained sixty-three counts which she desired the court to consider in making the decision, and the attorneys who heard the speech unanimously agree that it was a strong argument, free from female pyrotechnics and bristling with sound legal points that should cause some hesitation before the court decides against her.

She repeated her arguments made in her 1895 “Constitutional Rights of the Women of Indiana” and again cited In re Leach as precedent. The Indianapolis Sentinel described the proceedings:

Mrs. Gougar has been a practicing attorney for many years and although she has been refused admittance to the bar of the supreme court heretofore, yet she was permitted yesterday to take the prescribed oath of admission before commencing her argument, which was the third oral hearing ever presented to this court by a woman.

The Sentinel quoted Indiana Supreme Court Judge James McCabe: “Mrs. Gougar made one of the most forcible, logical and concise legal arguments ever made before this court.” Gougar’s extended argument can be accessed through Courts in the Classroom.

[16]"Indiana Women May Not Vote," Waterloo Daily Courier, February 26, 1897, 2; "Mrs. Gougar is Defiant," Fort Wayne Weekly Sentinel, May 26, 1897, 8; "Still Advancing," Indianapolis Sun, February 8, 1907, 4; "Senate Denies Women Right of Suffrage," Connersville Evening News, February 15, 1907, 8; Joint Resolution of Congress Proposing a Constitutional Amendment Extending the Right of Suffrage to Women, May 19, 1919; Ratified Amendments, 1795-1992, General Records of the United States Government, Record Group 11, accessed America’s Documents, National Archives; Paul Halsall, Modern History Sourcebook: The Passage of the 19th Amendment, 1919-1920, Articles from the New York Times, Fordham University, 1997, www.fordham.edu.

The Indiana Supreme Court ruled against Gougar in a “quick knock-out decision in which the supreme court announces that suffrage is not a right of the American people, but only a privilege, enjoyed as a grant from the government." Gougar was frustrated, but continued to work for women’s suffrage. She declared the courts to be “inconsistent” and announced that she would “agitate before Indiana state legislators” and continue to petition and speak before the Indiana General Assembly. Just a few months before her death in 1907, Gougar argued in support of a women’s suffrage bill before the Indiana House and then Senate. The Indianapolis Sun reported, “Helen M. Gougar, of Lafayette, who for 25 years has been advocating the cause throughout the length and breadth of the United States, for the sixth time addressed an Indiana legislature." The Connersville Evening News reported that the bill was known as the “Helen Gougar Bill.” Although it was voted down, Gougar was encouraged by how close the vote was (22 to 24 when struck down by the Senate).

The Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution gave women the right to vote in all elections. The U.S. House and Senate passed the amendment in 1919. In January 1920, the Indiana General Assembley ratified the amendment. When Tennessee became the necessary thirty-sixth state to ratify the amendment, it was adopted and women achieved full suffrage after a long struggle. For more information on the amendment see: “The 19th Amendment,” Featured Documents, National Archives & Records Administration; “Woman’s Suffrage Timeline,” Courts in the Classroom, Indiana Judicial Branch, www.in.gov/judiciary/citc/3572.htm.

[17] Photograph of Grave, "Helen M. Gougar," Spring Vale Cemetery, Lafayette, accessed Find-A-Grave; "Helen M Gougar Dead: Temperance Leader Was Member of Indiana Bar and a Political Worker," New York Times, June 7, 1907, 9; "Mrs. Helen M. Gougar Dead at Lafayette," Shelbyville Democrat, June 6, 1907, 1; "Helen M. Gougar Is Dead at Lafayette," Indianapolis News, June 6, 1907, 1, Indiana State Library, Indiana Newspaper Collection, microfilm.

On June 6, 1907 Gougar died in her Lafayette home. In her obituary, the Indianapolis News described Gougar as "one of the leading temperance workers and woman suffrage leaders in the United States." The paper went on to declare that Gougar was "one of the most remarkable women in Indiana and was regarded as one of the most effective orators in the middle West. She participated in political, temperance, religious, union labor and woman suffrage movements, and in every one her executive ability was of great value."