Location: 1205 Pleasant Point, Rome City, IN 46784 (Noble County, Indiana)

Installed 2013 Indiana Historical Bureau and Gene Stratton-Porter Memorial Society, Inc.

ID#: 57.2013.1

Text

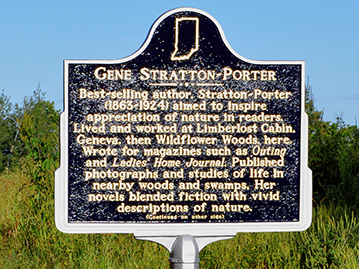

Side One:

Best-selling author, Stratton-Porter (1863-1924) aimed to inspire appreciation of nature in readers. Lived and worked at Limberlost Cabin, Geneva, then Wildflower Woods, here. Wrote for magazines such as Outing and Ladies’ Home Journal. Published photographs and studies of life in nearby woods and swamps. Her novels blended fiction with vivid descriptions of nature.

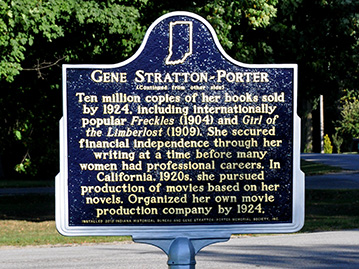

Side Two:

Ten million copies of her books sold by 1924, including internationally popular Freckles (1904) and Girl of the Limberlost (1909). She secured financial independence through her writing at a time before many women had professional careers. In California, 1920s, she pursued production of movies based on her novels. Organized her own movie production company by 1924.

Annotated Text

Best-selling author,[1] Stratton-Porter (1863-1924)[2] aimed to inspire appreciation of nature in readers.[3] Lived and worked at Limberlost Cabin, Geneva,[4] then Wildflower Woods, here.[5] Wrote for magazines such as Outing and Ladies’ Home Journal.[6] Published photographs and studies of life in nearby woods and swamps.[7] Her novels blended fiction with vivid descriptions of nature.[8]

Ten million copies of her books sold by 1924,[9] including internationally popular[10] Freckles (1904) and Girl of the Limberlost (1909).[11] She secured financial independence through her writing[12] at a time before many women had professional careers.[13] In California, 1920s, she pursued production of movies based on her novels.[14] Organized her own movie production company by 1924.[15]

*All letters from the Indiana State Museum (ISM) are copies produced by one of Stratton-Porter’s personal secretaries. All newspaper articles were gathered from NewspaperArchive.com unless otherwise indicated.

[1] “At Large Among the Literati,” Bakersfield Californian, December 2, 1921, 5; “Fiction in Demand at Public Libraries,” The Bookman, 54 (September 21-February, 1922): 592; “Our Taste in Reading,” Independent Helena Montana, January 27, 1924, 14; Oakland Tribune, September 21, 1913, n.p.; “Odd Bits About Women,” Burlington (Iowa) Hawk Eye, July 31, 1921, 1; “The ‘Best Seller’ Lady and Her Bird Books,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, August 15, 1915, n.p.; “Regarding Best Sellers,” Sandusky Register, August 4, 1921, 4; “In the Field of Fiction,” Syracuse Herald, July 25, 1921, 8; “Three Million Copies,” The Boston Sunday Globe, August 15, 1915, 4; “A Visit to the Bookshelves: Comparative Lists of ‘Best Sellers,’” Bakersfield Californian, October 21, 1922, n.p.; “Freckles as Play Popular as Book,” Perry Daily Chief, December 9, 1912, n.p.; Decatur Daily Democrat, July 30, 1913, n.p.; May Irene Copinger, “The Lady of the Limberlost: Gene Stratton-Porter’s Chief Pride was in Naturalist’s Work,” The Sun, September 30, 1928, MS13, accessed Proquest; “A Porter Story,” Decatur Daily Democrat, July 30, 1913, n.p.; S.F.E., Gene Stratton-Porter: A Little Story of The Life and Work and Ideals of “The Bird Woman” (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1915), 38; Lisa Mighetto, “Science, Sentinment, and Anxiety: American Nature Writing at the Turn of the Century,” Pacific Historical Review, 54:1 (February 1985): 42; Jeannette Porter Meehan, The Lady of the Limberlost: The Life and Letters of Gene Stratton-Porter (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928), 159; William Lyon Phelps, “Virtues of the Second-Rate,” The English Journal 16: 1 (January 1927):12-13; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mr. and Mrs. Robert Cochrane, n.d, Indiana State Museum (ISM); Carolyn Caywood, “Bigotry by the Book,” School Library Journal (December 1992): 41; Gene Stratton-Porter, “Books in the Home,” in Let Us Highly Resolve (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1927), 241.

Stratton-Porter sold millions of her books throughout her lifetime (see footnote #9) and some of these books appeared on best-sellers lists, particularly her fiction novels. For example, Stratton-Porter’s novel Her Father’s Daughter reached number two nationwide on Publisher Weekly’s best-seller list (1921) and number three on The Bookman’s best-seller list (1922). Another Stratton-Porter novel, The White Flag, ranked third on The Bookman’s best-seller list (1924). The Oakland (California) Tribune also proclaimed that her novel Laddie sold 200,000 advanced copies, which was one of the largest advanced sales of a book in the United States of all time. A 1921 article in the Burlington Hawk Eye even proclaimed Stratton-Porter the “Queen of the Bestsellers.” Many other newspaper articles allude to her best-seller status as well.

While Stratton-Porter’s books were widely popular, her work received little critical acclaim from reviewers of her time. Literary critics often dismissed her novels as sentimental and unrealistic “molasses fiction.” One reviewer, William Lyon Phelps, dubbed Stratton-Porter and other popular authors of her time the “Greatest Common Divisors.” While their writings might not have been considered great works of art, Phelps asserted that the wide appeal of these authors lay in their great ability to tell a compelling story and appeal to audience’s instinctive love of “courage, honor, truth, beauty, [and] magnanimity.” As such, Stratton-Porter’s rags-to-riches stories about morally upstanding characters interested many readers. The author explained in a letter to a fan, writing: “I know there are clean, moral, home-loving, home keeping men and women and of such I choose to write.”

Seeking to appeal to the widest audience, Stratton-Porter often reflected the traditional perspectives and values of her time. For example, many of her works contain blatantly racist sentiments that, while offensive today, did not raise many eyebrows among her contemporary readers. Most notably, Her Father’s Daughter centers on white Americans’ growing fear of the “Yellow Peril” in California. For more on representations of Asian-Americans in Stratton-Porter’s novels, see this University of California, Riverside website. Racism against African Americans appears in some of Stratton-Porter’s writings as well.

[2] 1870 United States Census, Lagro Township, Wabash County, Indiana, Roll M593_367, p. 53A, line 82, June 16, 1870, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1880 United States Census, Wabash Township, Wabash County, Indiana, Roll 315, June 9, 1880, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Among the Authors,” Publisher’s Weekly, August 20, 1921, 590, accessed googlebooks.com; 1900 United States Census, Wabash Township, Adams County, Indiana, June 8, 1900, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1910 United States Census, Wabash Township, Adams County, Indiana, 21 and 22, 1910, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Jeannette Porter Meehan, The Lady of the Limberlost: The Life and Letters of Gene Stratton-Porter (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928), 9; Judith Reick Long, Gene Stratton-Porter: Novelist and Naturalist (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1990), 41; Barbara Olenyik Morrow, Nature’s Storyteller: The Life of Gene Stratton-Porter (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2010), 19; “Fatally Hurt in California,” Indianapolis Star, December 7, 1924, n.p., accessed ISL clippings file; “Gene Stratton Porter Rites May be Held in Los Angeles,” Indianapolis Star, December 8, 1924, p.1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Porter Dies Following Auto Crash,” Indianapolis Star, December 7, 1924, 1-2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Gene Stratton-Porter,” Hollywood Forever Cemetery, Hollywood, Los Angeles, California, Find-a-grave.com.

Not all primary sources agree on Stratton-Porter’s date of birth. However, the preponderance of primary and secondary sources confirm that she was born in 1863. The earliest Census record of the author from 1870 stated that she was born “about 1864.” The 1880 Census also placed her birth year around 1864, while a 1921 article on Stratton-Porter in Publisher’s Weekly places the day of her birth on August 17. In addition, the 1870 Census marks Stratton-Porter as six-years-old when the Census was taken in June of that year. Since Stratton-Porter was born in August, she would turn seven a month after the Census was taken, thereby making her birth year 1863. Additionally, in the1880 Census, Stratton-Porter was recorded as 16 years old in June of that year. She would turn 17 a month later, again making her birth year 1863. The 1900 Census confirms her birth year as 1863.

The preponderance of secondary sources also corroborates her birth year as 1863, including her daughter’s biography of Stratton-Porter, in which she claims that Stratton-Porter was born on August 17, 1863. According to several obituaries, Gene Stratton-Porter died in an automobile accident on December 6, 1924. Her gravestone at the Gene Stratton-Porter State Historic Site on Sylvan Lake near Rome City, Indiana verifies this death date, as well as her birth date.

[3] Gene Stratton-Porter to Calvin Coolidge, August 22, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to A.E. Stillman, March 20, 1924, ISM; “Await Decision on Drainage Law,” Fort Wayne News and Sentinel, August 28, 1919, 1, sec. 2; “Report Disapproves Law about Drainage,” Indianapolis News, October 4, 1919, 2; accessed ISL microfilm; “Await Decision on New Drainage Law,” Indianapolis News, August 27, 1919, 3, accessed ISL microfilm; “Effect of Law on Lakes Considered,” Indianapolis News, 24, accessed ISL microfilm; “Makes Pleas for Drainage Act,” Fort Wayne News and Sentinel, August 27, 1919, 1; Gene S. Porter, “In the Camps of Croesus,” Recreation Magazine, 1900-1907, accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collections; Gene Stratton-Porter, “The Last Passenger Pigeon,” in American Earth: Environmental Writing Since Thoreau , ed. Bill McKibben (New York: Literary Classics of the United States, 2008), 192-205; Gene Stratton-Porter to A.E. Stillman, March 20, 1924, ISM; “C.D. Mead is Chosen as Second Vice President,” The Fort Wayne Sentinel, May 27, 1908, 10; “Machine Occupied by Hoosier Writer Collides with Los Angeles Street Car,” Indianapolis Star, Dec 7, 1924, p. 1-2; Gene Stratton-Porter to I.G.H. Barnes, September 19, 1923, ISM; Oakland (California) Tribune, September 18, 1921, 7; “Millions loved her,” Advertisement, New York Times, April 12, 1925, accessed ProQuest; Gene Stratton-Porter to Pearl Huntley, November 28, 1922, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter, Tales You Won’t Believe (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1925), p. 211-230; “Music of the Wild,” Decatur Daily Democrat, October 15, 1910, 1; Review of The Song of the Cardinal, The Arena 30: 2 (August 1903): 215; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mr. and Mrs. Robert Cochrane, n.d., 2, accessed ISM; Lisa Mighetto, “Science, Sentiment, and Anxiety: American Nature Writing at the Turn of the Century,” Pacific Historical Review 54, no. 1 (February 1985): 49; Gene Stratton-Porter to Richard Nida, February 2, 1924, accessed ISM; Eugene H. Pattison, “The Limberlost, Tinker Creek, Science and Society: Gene Stratton-Porter and Annie Dillard,” Pittsburgh History (Winter 1994/95): 160-161, accessed ISL clippings files; Annie Dillard, An American Childhood (New York: G.K. Hall, 1987): 161.

In addition to her career as an author, Gene Stratton-Porter was a naturalist, and to a lesser extent a conservationist, who took special interest in bird life. She dedicated much of her career to studying and writing about Indiana’s natural history, especially the Limberlost swamp. For more on Porter’s nature studies, see footnote # 7. Porter’s love of nature was also evident through her conservation work. In a 1923 letter she wrote, “…my heart is irrevocably bound up in the love of Nature, [and in] an overwhelming desire to preserve the beauty of the gift God has given us in this our great land.” The popular author was involved in at least two petitions against drainage laws, one in Limberlost, Indiana and another in Mississippi that threatened the natural habitats of many plant and wildlife species. When a proposal to drain the Limberlost swamp in Noble and Lagrange counties passed in 1919, Stratton-Porter and a group of concerned citizens argued that such a plan would destroy the natural habitats of many animals and destroy the lakes on which many Indiana citizens vacationed including Sylvan Lake in Rome City, where Stratton-Porter maintained a home. Porter also participated in conservation on a national level. In 1924, Porter wrote to President Calvin Coolidge urging him to put an end to a plan to drain the bottoms in Mississippi. She also signed a petition to preserve eagles and their habitats in the United States and was involved in several national nature organizations including the Audubon Society, National Geographic Society, and the American Reforestation Association.

Through her published writings, Stratton-Porter attempted to inspire this same love of nature in her readers. In 1922 she described her goal: “I would like to write a nature book that would pull every fat, jaundiced, sit-by-the-fire out in the fields and woods and open their hearts to the bigness and the beauties of Nature...” Many of Stratton-Porter’s works further contained messages cautioning readers against the destruction of natural environments. For example, in her 1925 book Tales You Won’t Believe, the author lamented the near extinction of the Passenger Pigeon in the United States due to over-hunting, and urged her readers not to kill rare birds.

Porter’s correspondence with her fans, as well as some reviews of her books in newspapers illustrate that she succeeded in instilling an appreciation of nature in many readers. One review of Music of the Wild proclaimed that “if you study it [the book], you will become not only a lover of nature but a sincere admirer of the writer.” A review of The Song of the Cardinal in The Arena magazine, also stated: “If the Audubon Society should circulate thousands of copies of this work, it would do far more to revolutionize public sentiment than the expenditure of the same amount of money in dry arguments or heated protests.” According to Stratton-Porter, A Girl of the Limberlost was being translated into Arabic for just this purpose, “to be introduced into the schools of that land as a first book calculated to inculcate a love of nature and open the way for nature study.”

In some cases, Stratton-Porter’s works inspired others to pursue conservation or nature writing. Broadly, historian Lisa Mighetto groups Stratton-Porter with other popular naturalists at the turn of the nineteenth century, such as John Muir and Ernest Thompson Seton, who appealed to readers’ emotions to inspire an appreciation of and desire to protect nature. According to Mighetto, the writings of these popular naturalists “helped rouse public support for preservationist proposals at the turn of the century.” For instance, Stratton-Porter’s books inspired a group of children in San Diego to form a Gene Stratton-Porter Boys’ Bird Club, which endeavored to establish a bird sanctuary in the area. One of Stratton-Porter’s letters to her young fans indicates that there was also a Girls’ Bird Club in San Diego. According to the article “The Limberlost, Tinker Creek, Science and Society: Gene Stratton-Porter and Annie Dillard,” Pulitzer prize-winning author Annie Dillard credited Porter’s Moths of the Limberlost with inspiring her interest in nature and science as a young student. Dillard later went on to write Pilgrim at Tinker Creek, “a meditative book on nature based in Virginia’s Roanoke Valley.”

[4] Gene Stratton-Porter to J.H. Heller, March 23, 1911, accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collections; “Geneva Stratton,” Wabash County, Indiana, Marriage Records 1882-1899, Book 11, p. 29; The Green Book Magazine, 15 (January 1916): 422, accessed googlebooks.com; “Gene Stratton-Porter,” Nature and Culture 3, no. 1 (June 1911): 16, accessed googlebooks.com; Gene Stratton-Porter, Moths of the Limberlost with Watercolor and Photographic Illustrations of Life (Garden City: Doubleday, Page, & Company, 1916), 8 and 14, accessed googlebooks.com; Gene Stratton-Porter, Homing with the Birds: The History of a Lifetime of Personal Experience with the Birds (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1920), xi, accessed googlebooks.com; Gene Stratton-Porter to John Heller, March 23, 1911, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter: A Little Story of the Life and Work and Ideals of “The Bird Woman” (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1915), 50-52; Jeannette Porter Meehan, The Lady of the Limberlost: The Life and Letters of Gene Stratton-Porter (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928), 179-180; “Says Limberlost is Now Prey to Commercialism,” Fort Wayne News and Sentinel, July 17, 1919, 15; “Is Moving North,” Decatur Daily Democrat, July 17, 1919, 5; “Gene Stratton-Porter Sells Limberlost Cabin,” Fort Wayne News and Sentinel, January 17, 1920, 6; “Limberlost Cottage Sold,” Decatur Daily Democrat, January 19, 1920, 1; “May Accept Second Memorial,” Kokomo Tribune, August 14, 1946, 7; “Limberlost Group is Incorporated,” Kokomo Tribune, August 29, 1946, 5.

In a 1911 letter, the author wrote that she was born on a farm outside of Wabash, Wabash County, Indiana where she lived until she was ten years old. Her family then moved into the city of Wabash, where she lived until she married Charles Porter in April 1886. She and her husband moved to Decatur, Indiana for a year before relocating to Geneva, Indiana. After living in various residences in Geneva, the Porters built a log cabin home near the town. Stratton-Porter referred to this house as “Limberlost Cabin” in her writings and correspondence. It was in this cabin and the nearby Limberlost Swamp that the author observed and photographed nature subjects for many of her natural science books. While the swamp lands originally served as an excellent source of material for Stratton-Porter’s works, the author lamented the rapid destruction of Limberlost by oil companies, loggers, and farmers in the area. A state drainage law passed in 1919 further threatened to destroy the entire swamp. Disruption of the natural habitats of Porter’s nature subjects, especially the birdlife, forced her to seek a more untouched environment for her studies; so she moved further north to Sylvan Lake in Rome City, Indiana (See footnote #5). Though it is unclear when she finally made Sylvan Lake her permanent residence, she officially sold the Limberlost Cabin in Geneva and the surrounding property to Dr. C.R. Price in 1920. Stratton-Porter’s home in Geneva is now a state historic site.

[5] Gene Stratton-Porter to Governor Warren T. McCray, August 2, 1923, ISM; “Builds Summer Cottage,” Indianapolis Star, June 9, 1913, n.p.; “About Authors,” The Washington Herald, March 22, 1922, 4, accessed Chronicling America; Gene Stratton-Porter, Homing with the Birds: The History of a Lifetime of Personal Experience with the Birds (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1920), 56, 66-68, accessed googlebooks.com ; Mrs. Frank N. Wallace, “Snowbound at Limberlost,” Indianapolis Star, February 25, 1940, n.p., accessed ISL clippings file; Gene Stratton-Porter, Tales You Won’t Believe (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1925), p. 82 and 231; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mr. and Mrs. Cochrane, n.d., p. 3, ISM; Jeannette Porter Meehan, The Lady of the Limberlost: The Life and Letters of Gene Stratton-Porter (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928), 179-180; Gene Stratton-Porter, Morning Face (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1916), 17; Gene Stratton-Porter to F.N. Wallace, October 26, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Henry A. Lorberg, January 24, 1924, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to F.N. Wallace, October 26, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Henry A. Lorberg, January 24, 1924; Warren T. McCray to Gene Stratton-Porter, (transcript), [August 15, 1923], ISM; “State Accepts Land for Porter Memorial,” Kokomo Tribune, July 17, 1946, 14; “Indiana Given Home of Gene Stratton Porter for Use as Memorial,” Valparaiso Vidette Messenger, July 19, 1946, 3; “Cities Insist on Increased State Refund,” Kokomo Tribune, November 15, 1946, 1.

In a 1923 letter, Stratton-Porter explained that she purchased property on Sylvan Lake with her own money. She wrote: “With the proceeds from my literary work in 1911 I purchased one hundred and twenty acres of land on the shores of the most beautiful lake [Sylvan Lake] I ever have seen, at Rome City, Indiana.” Her new sanctuary began as a summer home, but she moved there permanently after much of the southern half of Limberlost was destroyed (see Footnote #4). According to a 1913 article in the Indianapolis Star, she began erecting a new summer cottage on the site by 1913. Porter called her new home “Limberlost Cabin” as well and named the surrounding property “Wildflower Woods.” After the cabin in Rome City was complete, Porter referred to the Geneva cabin as Limberlost Cabin, South, and the Rome City cabin as Limberlost Cabin, North. After Stratton-Porter moved much of her business to California in the 1920s (see footnote #14), she sought to sell the cabin and Wildflower Woods to the State of Indiana to be preserved as a public park and bird sanctuary. Porter even appealed to the Governor, urging him to consider preserving her old home and land for citizens of the state to enjoy. However, the state initially showed little interest. Wildflower Woods is now a state historic site.

[6] Edward Bok, “Apropos of Our Birthday,” Ladies’ Home Journal, November 1903, 20, accessed through ProQuest; Douglas B. Ward, “The Geography of the Ladies’ Home Journal: An Analysis of a Magazine’s Audience, 1911-55,” Journalism History 34(1) (Spring 2008): 2-14; Long, Novelist and Naturalist, 228-9, “Gene Stratton-Porter’s Magazine Articles,” Our Land and Literature, Ball State University; Decatur Democrat, December 19, 1901, n.p.; Decatur Daily Democrat, October 30, 1903, 1; Gene Stratton-Porter to J.E. Ware, January 21, 1924, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Garnett E. Hall, March 7, 1924, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Constance L. Skinner, March 14, 1924, ISM; “A Series of Splendid Features,” Ladies’ Home Journal 23, no. 1 (December 1905): 2, accessed Proquest; “Greatest Stories-now in McCall’s,” Bridgeport [Connecticut] Telegram, March 16, 1922, 18; “Kitchens would be Different if Men Were the Cooks,” Manitowoc Herald News, September 27, 1923, n.p.; Gene S. Porter, “In the Camps of Croesus,” Recreation Magazine, 1900-1907, 21-22, accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collections; Gene Stratton-Porter to John Murray, December 17, 1923, ISM; [Gene Stratton-Porter] to F.N. Doubleday, February 14, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter, “Freckles’s Chickens,” Ladies’ Home Journal 21, no. 12 (November 1904): 9, accessed Proquest; Gene Stratton-Porter, “What I Have Done with Birds,” Ladies’ Home Journal 23, no. 5 (April 1906): 19, accessed Proquest; Gene Stratton-Porter, “The Gift of the Birds,” The Youth’s Companion, March 19, 1914, p. 147, accessed Proquest; Gene Stratton-Porter, “A Study of the Black Vulture,” Outing 39, no. 3 (December 1901): 279-283, accessed LA84Foundation.org; Gene Stratton-Porter, “The Music of the Marsh,” Outing 40, no. 6 (September 1902): 658-665, accessed LA84Foundation.org; Gene Stratton-Porter, “Bird Architecture,” Outing 38, no. 4 (July 1901): 437-442, accessed LA84Foundation.org; Gene Stratton-Porter, “Tales You Won’t Believe,” Good Housekeeping 78, no. 1 (January 1924): 16-17, 101, accessed Cornell University Home Economics Archive; Gene Stratton-Porter, “Euphorobia,” Good Housekeeping 76, no. 1 (January 1923): 10-13, accessed Cornell University Home Economics Archive; Gene Stratton-Porter, “The Kingdom Round the Corner,” Good Housekeeping 72, no. 1 (January 1921): 12, accessed Cornell University Home Economics Archive; Gene Stratton-Porter, “What My Father Meant to Me,” American Magazine (February 1926): 32, 70, 72, 76, accessed ISL clippings file; “Gene Stratton Porter Rites are Not Decided,” Indianapolis News, December 8, 1924, accessed ISL clippings file; Advertisement, London Daily Mail, October 25, 1922, 8; Gene Stratton-Porter to Charles D. Porter, May 24, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton Porter to F.N. Doubleday, February 14, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton Porter to Constance L. Skinner, March 14, 1924, ISM; “Porter Dies Following Auto Crash,” Indianapolis Star, December 7, 1924, 1-2.

Stratton-Porter wrote fictional short stories, poetry, and non-fiction nature study articles for a wide variety of magazines, including Outing, Recreation Magazine, Good Housekeeping, and Ladies’ Home Journal. In 1901 and 1902 she contributed articles to the magazine Outing describing her studies of the wildlife. In 1906, the Ladies’ Home Journal published her series, “What I Have Done with Birds,” which reached over a million readers. (For more information on the Ladies Home Journal see the “Juliet V. Strauss” state historical marker and research file. According to Long’s biography, Stratton-Porter began writing for McCall’s Magazine in 1921. For this magazine, Stratton-Porter mainly wrote monthly editorials filled with advice for the American housewife.

While she did not think very highly of the magazine or the type of writing she did for this publication, Stratton-Porter viewed McCall’s as an avenue through which to gain wider recognition for her name and her work, especially as she ventured into the world of film production. She wrote, “There is nothing first class about McCall’s. It is distinctly third rate.” However, through this publication, other magazines, and syndications of her works in newspapers Stratton-Porter saw an opportunity to “[make] my work known to people who never heard of me…I have a feeling that the wider I can make my name known through various channels, the different people I can reach just now when I am embarking in the picture business will all work together toward building up the book property.” Some of Stratton-Porters’ McCall’s articles were reprinted in an anthology published by Doubleday and Page. Good Housekeeping published her fictional stories and poetry beginning in 1921, and ceased only with her death. According to The Indianapolis Star, Stratton-Porter served as the editor of Recreation Magazine’s camera department, served four years as a natural history photography specialist for the Photographic Times annual almanac, and was a member of the natural history staff of Outing Magazine.

Our Land, Our Literature, a Ball State University project, hosts a bibliography of magazine articles written by Stratton-Porter. This bibliography lists several other magazines that she contributed to: The American Annual of Photography and Photographic Times Almanac, American Magazine, Biennial Report of the Commissioner of Fisheries & Fame for Indiana, Country Life in American, Current Literature, Izaak Walton League Monthly, Literary Digest, Metropolitan Magazine, New York Times Magazine, Outdoor America, Recreation, Red Cross Magazine, Women at Home Magazine, and World’s Work. Further research is needed to confirm this information.

[7] Gene Stratton-Porter to F.N. Doubleday, February 14, 1923, ISM; “Books in Brief Review,” The New York Times, November 23, 1919, BR6, accessed Proquest; Gene Gene Stratton-Porter, “What I Have Done with Birds,” Ladies’ Home Journal 23: 9 (August 1906): 19, accessed Proquest; Gene Stratton-Porter, “Nature Notes made at Limberlost Cabin (North), Began August 17, 1914,” ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mr. Heller, October 20, 1910, accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collection; “Author of the ‘Limberlost’ and ‘Freckles’ Writes of Her Friends of the Woods and Fields,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, July 28, 1912, n.p.; Kevin Armitage, “On Gene Stratton Porter’s Conservation Aesthetic,” Environmental History 14:1 (January 2009): 138-145; Judith Reick Long, Gene Stratton-Porter: Novelist and Naturalist (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1990), 180; “C.D. Mead is Chosen as Second Vice President,” The Fort Wayne Sentinel, May 27, 1908, 10; Gene Stratton-Porter, What I Have Done with Birds: character studies of native American birds which, through friendly advances, I induced to pose for me, or succeeded in photographing by good fortune, with the story of my experiences in obtaining their pictures (Indianapolis:Bobbs-Merrill Co., 1907); Gene Stratton-Porter, Birds of the Bible (Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham, 1909); Gene Stratton-Porter, Music of the Wild, with Reproductions of the Performers, Their Instruments and Festival Halls (Cincinnati: Jennings and Graham, [1910]); Gene Stratton-Porter, Moths of the Limberlost: with color and photographic illustrations from life (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1912); Gene Stratton-Porter, Homing with The Birds: the history of a lifetime of personal experience with the birds (Garden City: Doubleday, 1919); Gene Stratton-Porter, Tales You Won’t Believe (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Co., 1925); Thomas S. Edwards and Elizabeth A. De Wolfe, eds., Such News of the Land: U.S. Women Nature Writers (Hanover: University Press of New England, 2001), 72, accessed googlebooks.com; Reick Long, Novelist and Naturalist, 7; Stratton-Porter to John Heller and Frank Quinn, March 24, 1924, ISM;.

Of all the different types of writing Stratton-Porter did throughout her career, she enjoyed writing nature studies the most. In a 1923 letter she wrote, “…next to poetry I would most rather do natural history than anything else on earth.” Yet in reality, these books were less lucrative. Stratton-Porter began writing her more financially successful fiction novels to fund her nature work, and secured an agreement with her publisher, Doubleday, Page & Co., that they would publish one nature study for every novel she wrote. The Indiana author worked extensively in the natural habitats surrounding her homes in Geneva and Rome City, Indiana to gather material for these books. With a camera and notebook in hand, she ventured into the woods to observe and record the activities of wildlife she encountered.

Stratton-Porter was known for her engaging, anecdotal writing style in her nature studies. Unlike many scientific studies of the time, Stratton-Porter avoided jargon and dense language that often alienated general readers. In the 2009 article “On Gene Stratton Porter’s Conservation Aesthetic,” Kevin Armitage points out that Porter’s nature work did not strive to be “objective science.” Instead, she wrote about her personal observations of nature in empathetic and emotive terms that appealed to the general public. For example, she often assigned human characteristics to the birds she described to help readers identify with the creatures.

Another aspect that set her nature books apart from other studies was the photographic illustrations. Many naturalists illustrated their books with drawings, which Stratton-Porter viewed as un-lifelike. The Indiana author, however, was known for her particular prowess in capturing rare photographs of birds and other wildlife in their natural habitats. She began experimenting with photography when she discovered that many publishers would not publish her writing without illustrations. In a May 1908 newspaper article, Stratton-Porter explained, “I could not get my articles accepted by the editors unless they were illustrated and this brought, naturally, the camera and it was then, I believe, that I found my mission in life. Since that time I have followed the birds to their lairs; I have photographed them in every conceivable state of life and condition.” Porter wrote several nature studies including What I Have Done With Birds (1907), Birds of the Bible (1909), Music of the Wild (1910), Moths of the Limberlost (1912), Homing with the Birds (1919), and Tales You Won’t Believe (1925). Some of her nature studies were printed or reprinted in magazine publications. For example, excerpts of What I Have Done with Birds appeared in Ladies’ Home Journal in 1906. Many of Stratton-Porter’s photographs can be found in the collections of the Indiana State Museum.

Despite the relative popularity of her nature work, Stratton-Porter’s nature studies, like her fiction novels, often drew criticism from the scholarly community. Scientists dismissed her work as “unscientific” in its personal approach to nature observation. The Indiana author expressed her disappointment at the critical response to her nature studies in a 1924 letter, writing: “In my own case the thing that has hurt me the deepest has been to put all the brains I had, the greater part of my time, and immense sums of my earnings into the natural history work and then to have the critics of the country calmly ignore such intimate photographic work of the birds as no one ever has accomplished before [sic] and the store of scientific natural history material that I have brought from the fields and woods…”

[8] Anne K. Phillips, “Of Epiphanies and Poets: Gene Stratton-Porter’s Domestic Transcendentalism,” Children’s Literature Association Quarterly 19: 4 (Winter 1994): 154; Janet Malcolm, “Capitalist Pastorale,” New York Review of Books, January 15, 2009, 5-6, accessed New York Review of Books; Eugene Francis Saxton, Gene Stratton-Porter: A Little Story of the Life and Work and Ideals of the “Bird Woman” (Garden City: Doubleday, Page, & Co., 1915), 22, 35-37; “Books by Mrs. Porter,” Decatur Daily Democrat, October 20, 1910, n.p., accessed Indiana Memory Digital Collections; “Gene Stratton Porter,” Oakland [California] Tribune, September 18, 1921, S-7; “Stories About Our Favorite Authors,” Winnipeg Free Press, October 7, 1922, n.p.; “Mrs. Stratton-Porter’s Last Work,” New York Times, August 16, 1925, BR7, accessed Proquest; Kevin Armitage, “On Gene Stratton Porter’s Conservation Aesthetic,” Environmental History 14: 1 (January 2009): 141; Kevin C. Armitage, The Nature Study Movement: The Forgotten Popularizer of America’s Conservation Ethic (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2009), 167; “Gene Stratton-Porter and Her Nine Millions,” Burton Evening Transcript, September 24, 1921, accessed ISL clippings file; Gene Stratton-Porter, The Song of the Cardinal: A Love Story (Indianapolis: Bobbs-Merrill Company, 1903); Gene Stratton-Porter, Freckles (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1904); Gene Stratton-Porter, At the Foot of the Rainbow (Printed by Doubleday, Page for Nelson Doubleday, 1907); Gene Stratton-Porter, Girl of the Limberlost (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1910 [c1909]); Gene Stratton-Porter, The Harvester (Doubleday, Page & Company, 1911); Gene Stratton-Porter, Laddie: A True Blue Story (Doubleday, Page & company, 1913); Gene Stratton-Porter, Michael O’Halloran (Doubleday, Page & company, 1915); Gene Stratton-Porter, Daughter of the Land (Doubleday, 1918); Gene Stratton-Porter, Her Father’s Daughter (Doubleday, Page & Co., 1921); Gene Stratton-Porter, The White Flag (Doubleday, Page & Co., 1923); Gene Stratton-Porter, The Keeper of the Bees (Doubleday, Page & Co., 1925); Gene Stratton-Porter, The Magic Garden (Doubleday, Page, 1927).

Nature featured prominently in most of Stratton-Porter’s writings, including her fiction stories and novels. In addition to setting her stories in picturesque country landscapes, Porter often developed main characters that had close ties to nature. For example, in Freckles, the title character works as a guard for a timber company and spends his days in the woods of the Limberlost swamp. In Girl of the Limberlost, the main character Elnora Comstock is an avid collector of moths and other natural specimens. Also, The Harvester’s main male character lives in the woods and uses his knowledge of plant life to earn a living selling medicinal herbs and remedies.

In 1904, Stratton-Porter completed Freckles, one of her first novels to feature the signature blend of nature study and fiction, or as she described it “nature studies sugar coated with fiction.” According to several newspaper articles and other sources, publishers were initially skeptical that a fiction novel so heavily laden with natural history could attract a wide readership. Although they requested that she “replace some of the ‘nature talk,’” Stratton-Porter made few changes. The novel proved to be a commercial success, despite the publisher’s reservations; and according to the Decatur Daily Democrat, the popularity of her nature-fiction formula, changed the editor’s mind. The paper stated, “Now the cry of the publishers is ‘a little more nature please,’ or ‘can’t you arrange to give us one of your charming nature stories this year.”

Realizing that fewer readers were likely to purchase a non-fiction book of natural history, Porter used popular fiction as a means through which to deliver her nature work to a broader audience. According to the Oakland Tribune, Porter wrote her first fiction novel “for the express purpose of putting nature work before the people in a form in which they would accept it.” Amidst her fictional stories, Stratton-Porter managed to weave natural history information that allowed readers to learn about nature, and thus further appreciate it. For example in her novel Keeper of the Bees, one reviewer noted that the book “has its horticultural interludes aplenty. Along with these, very naturally enough, runs much informative material on the bee industry.” Stratton-Porter’s fiction novels include The Song of the Cardinal (1903), Freckles (1904), At the Foot of the Rainbow (1907), A Girl of the Limberlost (1909), The Harvester (1911), Laddie: A True Blue Story (1913), Michael O’Halloran (1915), Daughter of the Land (1918), Her Father’s Daughter (1921), The White Flag (1923), The Keeper of the Bees (1925), and The Magic Garden (1927).

[9] “Her Father’s Daughter Wins the Applause of New Thousands for Gene Stratton-Porter,” Advertisement, New York Times, December 18, 1921, 48, accessed ProQuest; “James Oliver Curwood and Gene Stratton-Porter,” Indianapolis Star, January 23, 1923, 10; Advertisement, New York Times, August 19, 1923, BR19, accessed ProQuest; Joseph O’Sullivan, “Is Woman Man’s Mental Equal?” Ada [Oklahoma] Evening News, January 13, 1924, 4; Arthur W. Shumaker, A History of Indiana Literature (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1962), 405.

Gene Stratton-Porter gained a large following throughout the early decades of the 1900s. According to a 1921 advertisement in the New York Times, by that year, over nine million copies of her books had already been sold. The Indianapolis Star reported the number at nearly ten million on January 23, 1923, and the following year an article in the Ada Evening News stated that Stratton-Porter’s books had sold more than ten million copies to date. Reflecting on her book sales, a New York Times advertisement described it as “an index to the appeal her writing has for the great reading public.” The periodical continued “none of her novels has sold less than 450,000; one has nearly reached the 2,000,000 mark.” For more on Stratton-Porter’s best-selling status see footnote #1.

[10] “Laddie—A True Blue Story,” Decatur Daily Democrat, September 19, 1913, n.p; “Mrs. Porter’s Books in Europe,” Decatur Daily Democrat, June 29, 1915, 1; “How to Make a Home,” Advertisement, London Daily Mail, October 25, 1922, 8; “From Mr. Murray’s List,” Advertisement, The Manchester Guardian, December 7, 1915, p. 4, accessed Proquest; “Hodder & Stoughton’s Christmas List,” Advertisement, The Manchester Guardian, December 8, 1914, 4; “Doubleday, Page & Co.,” The Atlanta [Georgia] Constitution, October 24, 1915, 1; “Popular Novels at 35¢,” Advertisement, Manitoba [Winnipeg] Free Press, November 2, 1916, 12; “Reprint Books,” Advertisement, Lethbridge [Canada] Herald, September 18, 1918, 1; “Popular Fiction By the Leading Authors at 95¢,” Advertisement, Winnipeg Free Press, May 6, 1920, 4; Advertisement, Kingston [Jamaica] Gleaner, September 3, 1919; “New Novels Just Arrived at Garner’s,” Advertisement, Kingston Gleaner, June 28, 1921, 2; “Favorite Novels Priced 75¢,” Winnipeg Free Press, December 18, 1923, 24; “Here Are More Titles of Cloth Bound Novels,” Kingston Gleaner, April 10, 1924, [9]; “Porter Novels Filmed,” Oakland Tribune, October 8, 1922, 4-W, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “A Porter Story,” Decatur Daily Democrat, July 30, 1913, n.p.; Jeannette Porter Meehan, The Lady of the Limberlost: The Life and Letters of Gene Stratton-Porter (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928), 134-178; Advertisement, New York Times, November 30, 1913, BR687; “Gene Stratton Porter,” Findlay [Ohio] Morning Republican, December 12, 1924, 4; “Other Popular Books in Cooper’s Library,” Oakland Tribune, November 25, 1911, 9; May Irene Copinger, “The Lady of the Limberlost: Gene Stratton Porter’s Chief Pride Was in Naturalist’s Work,” The Sun, September 30, 1928, MS13, accessed Proquest; Gene Stratton-Porter to John Heller and Frank Quinn, March 24, 1924, ISM; “Gene Stratton Porter” Oakland [California] Tribune, September 18, 1921, S-7. For fan letters, see Gene Stratton-Porter Collection, ISM.

Gene Stratton-Porter’s works gained popularity on both a national and international level. Speaking to her national significance, an advertisement in the Decatur Daily Democrat boasted that one could get a copy of her novel Laddie “in every book shop from New York to Seattle.” Internationally, her books were especially popular in England and appeared in several advertisements in that country’s newspapers. In fact, the Atlanta [Georgia] Constitution identified Porter as one of the most popular novelists in England. Advertisements for Stratton-Porter’s books also appeared in Canadian and Jamaican newspapers. According to the Oakland Tribune, the author boasted, “These books have made their way around the world, wherever English is understood, and have been translated into seven foreign tongues, and many of them raised in Braille print for the blind.” A variety of her books were also translated into Scandinavian, German, French, and Arabic, among other languages.

A collection of Stratton-Porter correspondence from the 1920s at the Indiana State Museum contains numerous fan letters from across the nation which attest to her popularity in the United States. However, her fan base extended beyond her native country. In 1913, Stratton-Porter proclaimed, “I have such letters in heaps, from every class and condition of people, all the way from northern Canada to the lowest tip of Africa, all asking for more of the outdoors…” Jeannette Meehan Porter, Stratton Porter’s daughter, wrote a biography of her mother in which she reprinted several of the international fan letters that Stratton-Porter received in response to Freckles, The Harvester, Moths of the Limberlost, and Laddie, among others. According to Meehan, the letters came from all over the world, including England, China, India, South Africa, and France.

[11] “Gene Stratton-Porter,” Our Land, Our Literature, Ball State University, http://landandlit.iweb.bsu.edu/Literature/Authors/portergs.htm; Gene Stratton-Porter, A Girl of the Limberlost (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1909); Gene Stratton-Porter, Freckles (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, 1904); “Author of the ‘Limberlost’ and ‘Freckles’ Writes of Her Friends of the Woods and Fields,” Fort Wayne Journal-Gazette, July 28, 1912, n.p.; “Would You Marry This Man?” Advertisement, Bode (Iowa) Bugle, October 25, 1918, n.p.; “Wanted: Better Daughters Says Gene Stratton Porter,” Charleston Daily Mail, December 11, 1921, 2; “Gene Stratton-Porter Lauds Silken Hose, But Raps High Heels,” Joplin (Missouri) Globe, August 27, 1922, 13; “Will Be Missed,” Olean (New York) Times, December 20, 1924, 16; “Kitchens Would Be Different If Men Were the Cooks,” The Manitowoc (Wisconsin) Herald-News, September 27, 1929, [3]; “Hodder & Stoughton’s Christmas List,” The Manchester Guardian, December 8, 1914, 4, accessed Proquest; “Mrs. Porter’s Books in Europe,” Decatur Daily Democrat, June 29, 1915, 1; “Popular Novels at 35¢,” Manitoba (Winnipeg) Free Press, November 2, 1916, 12; “Doubleday, Page & Co.,” The Atlanta (Georgia) Constitution, October 24, 1915, 1; “What Authors and Publishers are Doing,” New York Times, February 4, 1917, BR6; Advertisement, New York Times, August 14, 1909, 491; “‘Freckles’ Monday,” Sandusky Star Journal, September 28, 1912, 10; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mr. and Mrs. Robert Cochrane, n.d., p. 2, ISM; “Noted Woman Writer Killed in Collision,” Bakersfield (California) Morning Echo, December 7, 1924, 1; “Praise Her,” The (Decatur, IN) Daily Democrat, November 3, 1904, 1; Jeannette Porter Meehan, Lady of the Limberlost: The Life and Letters of Gene Stratton-Porter (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928), 134-150.

According to Our Land, Our Literature, Ball State University’s online educational resource on Indiana’s environmental literature, Freckles (1904) and Girl of the Limberlost (1909) were Gene Stratton-Porter’s most popular books and continue to be among the most well-known of her writings. These two novels appeared frequently in newspaper articles on the author and in advertisements for Stratton-Porter’s other books and articles. Freckles and Girl of the Limberlost were also featured in lists of “popular novels” in the United States, Canada, and the United Kingdom. One article in the Decatur Daily Democrat even claimed Freckles was so popular in England that Porter’s British publisher, John Murray, struggled to keep the book in stock and had sold 250 thousand copies by 1915. These books were also translated into several languages. For example, Freckles was translated into Spanish and Girl of the Limberlost was translated into Arabic. According to Porter-Meehan’s biography of the Indiana author, Stratton-Porter received worldwide attention for these novels as evidenced by her fan mail.

[12] Gene Stratton Porter, “Having Fun with Your Money,” Let Us Highly Resolve (Garden City: Doubleday, Page & Company, 1927), 223-231; For her property purchase in the Sierra Madres, see Gene Stratton-Porter to Robert Cochrane, January 8, 1924, ISM and Gene Stratton-Porter to W.H. Miner, January 21, 1924, ISM; For her property purchase on Catalina Island see Gene Stratton-Porter to Charles D. Porter, May 24, 1923, p. 3, ISM; Gene Statton-Porter to Mrs. F.N. Wallace, January 12, 1924, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to John A. Cronin, October 16, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mrs. Frank B. Parker, February 27, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Ida De Forest Barnard, May 29, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Charles Wilding, September 15, 1924, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mrs. Edward Kerr, September 5, 1924, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to John Heller and Frank Quinn, March 24, 1924, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Jas. S. Lawshe, August 6, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to John Heller, March 24, 1924, ISM; For more on Gene Stratton-Porter handling her finances, see Gene Stratton-Porter to Charles D. Porter, May 24, 1923, ISM.

Stratton-Porter was successful enough as an author to earn a substantial living from her photography, books, and other writings. In a McCall’s article titled “Having Fun with Your Money,” the Indiana author wrote about earning her own money, opening her own bank account, and the joys of financial freedom. Stratton-Porter stated, “There is a sort of heady exhilaration about being able to look the world in the face and feel that you are equal to it; that you can take care of yourself, and other if necessary, by your own individual efforts.” With her earnings, she purchased the land for Wildflower Woods, and later, properties on Catalina Island and in the Sierra Madres of California. She also financed the construction of cabins at each site. Although she wrote about disapproving of women participating in business, Stratton-Porter made several business investments. For example, she invested her own money in her husband’s bank, Bank of Geneva, and a brush and broom manufacturer. She also financed and organized her own film company in California, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions (See footnote #15).

Not only did Stratton-Porter achieve financial independence for herself, but she also assumed responsibility for supporting several family members, including her daughter Jeanette and her grandchildren. In one letter, Stratton-Porter explained to a fan that she supported a family of nine in her household, as well as “five separate and distinct families in homes, and I am furnishing and helping a large number of other people closely related.” Another letter indicated that Stratton-Porter handled her own financial affairs and set up trusts for her niece Mary Leah Stratton, her sisters Florence Compton and Ada Wilson, and Jeannette.

[13] Laura F. Edwards, “Gender and the Changing Roles of Women,” in A Companion to 19th-Century America, ed. William L. Barney (Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2001), 223-237; Gerda Lerner, The Majority Finds Its Past (New York: Oxford University Press, 1979); Ronald Weber, The Midwestern Ascendancy in American Writing (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1992); Robert A. Divine, T.H. Breen, George M. Fredrickson, R. Hal Williams, The American Story, Volume Two, Since 1865 (New York: Penguin Academics, 2002), 592; Mary Rech Rockwell, “Gender Transformations: The Gilded Age and the Roaring Twenties,” Organization of American Historians Magazine of History (2005) 19 (2): 31-40; Kevin C. Armitage, The Nature Study Movement: The Forgotten Popularizer of America’s Conservation Ethic (Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 2009), 165-8.

Stratton-Porter began her writing career at the turn of the century, before many middle or upper class white women worked outside of the home. In 1900, only 5% of married white women worked outside the home, according to the anthology, The American Story. Stratton-Porter did not encourage women to work outside the home or become involved in business in her magazine articles. Nonetheless, not only did she enter the male-dominated career fields of writing and nature study, she managed to reach an international audience (see footnote # 10). According to Armitage, her novels allowed Stratton-Porter to achieve financial success, while nature photographs—and later, articles—“allowed her to enter the world of published, and thereby professional work.” Also, Stratton-Porter was one of few women considered a member of the group of best-selling authors who made up the “Golden Age of Indiana Literature.” Other authors of this period, roughly the 1870s through the 1930s, included Booth Tarkington, James Whitcomb Riley, Theodore Dreiser, and Lew Wallace. For other examples of Indiana women writers reaching national audiences, see marker files for Virginia C. Meredith and Juliet V. Strauss, accessible at the Indiana Historical Bureau.

[14] “Noted Woman Author Dies After Crash,” Oelwein [Iowa] Daily Register, December 8, 1924, 1; Advertisement, Titusville [Pennsylvania] Herald, September 3, 1917, 4; “Freckles,” Hutchinson [Kansas] News, August 25, 1917, 14; “‘Freckles’ at the Alhambra Sunday and Monday,” Ogden (City Utah) Standard, June 2, 1917, 7; “Film Flickerings,” Fort Wayne News Sentinel, October 14, 1922, 9; “Screen Close Ups,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 31, 1922, B2, accessed Proquest; “The Talk Side of the Movies,” Washington Times, September 28, 1922, 20; “Porter Novels Filmed,” Oakland Tribune, October 8, 1922, 4-W; “Gene Stratton Porter to Film her Novels,” Decatur Daily Democrat, October 21, 1922, n.p.; “‘The Harvester’ Filmed with Hoosier Setting,” Indianapolis Star, June 12, 1927, accessed ISL clippings file; Eric Grayson, “Limberlost Found: Indiana’s Literary Legacy In Hollywood,” Traces (Winter 2007): 42-47; American Film Institute, “Gene Stratton Porter Productions,” Catalogue of Feature Films, accessed www.afi.com; American Film Institute, “Michael O’Halloran,” Catalogue of Feature Films, accessed www.afi.com; American Film Institute, “Laddie,” Catalogue of Feature Films, accessed www.afi.com; American Film Institute, “Freckles,” Catalogue of Feature Films, accessed www.afi.com; “Mrs. Porter to Abandon Limberlost,” Los Angeles Times, March 27, 1924, p. A1, accessed ProQuest; Gene Stratton-Porter to W.H. Miner, January 21, 1924, ISM; “Gene Stratton Porter,” Oakland [California] Tribune, September 18, 1921, S-7; Gene Stratton-Porter to Charles D. Porter, May 24, 1923, ISM; “Index to Register of Voters,” Los Angeles City Precinct No. 562, Los Angeles County, California, 1924, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mrs. F.N. Wallace, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Robert Cochrane, January 8, 1924, ISM; Reick Long, Novelist and Naturalist, 246-247.

According to an article in the Oelwein Daily Register, Porter began living part-time in California in 1919. Porter ventured to California, in part, to begin producing movie versions of some of her novels. The first Gene Stratton-Porter book to be made into a film was Freckles (1917) by Paramount Pictures. Eventually, Stratton-Porter formed her own film company (see footnote #15), and Michael O’Halloran was the first film produced by the company, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions. Porter expressed interest in filming The Girl of the Limberlost, The Harvester, The Fire Bird, Her Father’s Daughter, Laddie, Daughter of the Land, and At the Foot of the Rainbow. According to the 2007 article “Limberlost Found: Indiana’s Literary Legacy in Hollywood,” the company actually produced seven films before and after Porter’s death, including Michael O’Halloran (1923), A Girl of the Limberlost (1924), The Keeper of the Bees (1925), Laddie (1926), The Magic Garden (1927), The Harvester (1927), and Freckles (1928). The American Film Institute confirms that Gene Stratton-Porter Productions produced five of these films. Further primary source research is required to determine if all seven films were in fact produced by Gene Stratton-Porter Productions.

While it is unclear whether or not she became a California resident before her death in 1924, many primary sources suggest that Stratton-Porter did decide to make the western state her permanent home. In a letter to William H. Miner, the author wrote, “I have now definitely decided on California as a home for the remainder of my time. I have moved the contents of the Cabin from the lake in northern Indiana and I am going to make an effort to have either the State or the nation take over that place…” Stratton-Porter also detailed her future plans in a 1923 letter to her husband: “Since Jeannette is planning to marry and settle here with the children, since I am tied up here for years with picture work, and since I feel more at home among other authors and artists in California than I ever felt [sic] any place else on earth, I have almost definitely decided to make the move here and make it for good.” While in California, Stratton-Porter lived at various residences in Los Angeles, including a house on South Serrano Avenue. Striving to recreate her Indiana nature sanctuary in California, the author also purchased land on a small mountainside in present day Bel Air, where she began constructing a cabin-style mansion from which to conduct further nature studies. The home was not completed before her death. Stratton-Porter also fell in love with the natural beauty of California’s Catalina Island, where she built a vacation home.

[15] Gene Stratton-Porter to Gerritt Fitch, March 14, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Mrs. Frank B. Parker, February 27, 1923, ISM; Gene Stratton-Porter to Jas. S. Lawshe, August 6, 1923, ISM; “Screen Close Ups,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 31, 1922, B2, accessed Proquest; “Noted Woman Writer Killed in Collision,” Bakersfield (California) Morning Echo, December 7, 1924, 1; “Noted Woman Author Dies After Crash,” Oelwein (Iowa) Daily Register, December 8, 1924, 1; [Gene Stratton-Porter] to Flo S. Compton, April 3, [?], [p.2], ISM; “‘The Harvester’ Filmed with Hoosier Setting,” Indianapolis Star, June 12, 1927, accessed ISL clippings file. “Gene Stratton Porter to Film Her Novels,” Decatur [Indiana] Daily Democrat, October 21, 1922, n.p.; Gene Stratton-Porter to Flo S. Compton, April 3 [?], “‘The Harvester’ Filmed with Hoosier Setting,” Indianapolis Star, June 12, 1927, n.p., accessed ISL Clippings File; Jeanette Porter Meehan, Lady of the Limberlost: The Life and Letters of Gene Stratton-Porter (Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc., 1928), 274; Reick Long, Novelist and Naturalist, 238-239.

After Paramount Pictures finished filming Freckles in 1917, Stratton-Porter disliked the end product so much that she decided to create her own movie production company to film more of her novels. In 1923, she explained, “Years ago I tried the filming of one book through a picture company, and was so dissatisfied that I waited until I felt able to handle the venture myself.” By February 1923, she had begun organizing her own film company, Gene Stratton-Porter Productions Company. She wrote to a fan, “…I have just undertaken the personal organization of a company for the filming of those of my books suitable for the purpose.” Stratton-Porter funded the company, at least in part, with the money she earned from her writing and nature photography. Stratton-Porter’s daughter Jeannette acted as assistant director and worked alongside her future husband, James Meehan, who served as film director in the company. Jeannette Porter and James Meehan married in 1923.