Location: 1901 E. Washington St., Indianapolis, Indiana 46201

Installed 2019 Indiana Historical Bureau, Indiana School for the Deaf, and Indiana School for the Deaf Alumni Association

ID#: 49.2019.5

Text

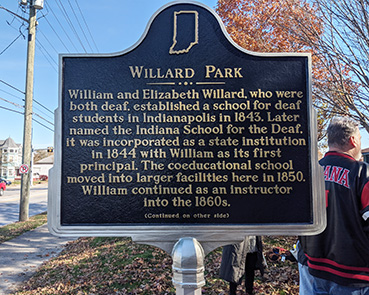

Side One:

William and Elizabeth Willard, who were both deaf, established a school for deaf students in Indianapolis in 1843. Later named the Indiana School for the Deaf, it was incorporated as a state institution in 1844 with William as its first principal. The coeducational school moved into larger facilities here in 1850. William continued as an instructor into the 1860s.

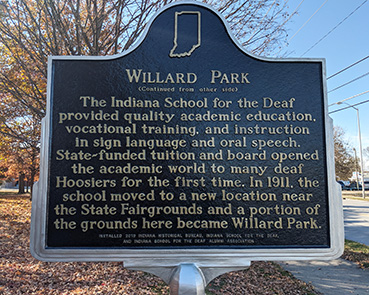

Side Two:

The Indiana School for the Deaf provided quality academic education, vocational training, and instruction in sign language and oral speech. State-funded tuition and board opened the academic world to many deaf Hoosiers for the first time. In 1911, the school moved to a new location near the State Fairgrounds and a portion of the grounds here became Willard Park.

Annotated Text

Side One

William and Eliza Willard, who were both deaf,[1] established a school for deaf students in Indianapolis in 1843.[2] Incorporated as a state institution in 1844,[3] it was later named the Indiana School for the Deaf.[4] The growing, coeducational school moved into larger facilities here, in 1850.[5] William Willard served first as principal and then as an instructor into the 1860s.[6]

Side Two

The Indiana School for the Deaf provided quality academic education, vocational training,[7] and instruction in sign language and oral speech.[8] State-funded tuition and board[9] opened the academic world to many deaf Hoosiers for the first time.[10] In 1911, the school moved to a new location near the State Fairgrounds[11] and a portion of the grounds here became Willard Park.[12]

[1] William Willard and Eliza Young, September 17, 1839, Butler, Ohio, County Marriage Records, Film Number 000355779, Ancestry.com; 1860 United States Federal Census, Schedule 1, Center Township, Marion County, Indiana, June 1, 1860, Roll M653_280, Page 746, Lines 9-10, accessed AncestryLibrary.

[2] “County Revenue – Tax – Bounty on Silk,” Richmond Weekly, June 10, 1843, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; William Willard, “School for Deaf and Dumb,” May 31, 1941 Announcement in Wabash Courier, July 1, 1843, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Samuel Bigger, “Governor’s Message,” December 5, 1843 published in Richmond Palladium, December 8, 1843, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; First Annual Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the Legislature of the State of Indiana, for the Year 1845 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1845)

1870 United States Federal Census, Schedule 1, 9 Ward, Subdivision 20, Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana, February 14, 1870, Roll M593, Page 42, Lines 10-11, accessed AncestryLibrary.

While only William Willard is credited by secondary sources as the school founder, primary show that the institution was started through the combined efforts of both William and Eliza Willard. And while even William may not have considered her an equal partner at the time (because of entrenched views on women’s inferiority and/or unsuitability to serving in the public sphere), it’s clear that she was heavily involved in its founding and opening. William’s 1843 announcement of the school’s opening, published in several Indiana newspapers, stated:

I will on the first Monday in October next, open an Institution in Indianapolis . . . I will not only personally instruct, but constantly superintend the manners and morals of the pupils . . . The females will be under the additional oversight of Mrs. Willard, both in instruction and care.

Governor Samuel Bigger, on the other hand, clearly credited both Willards with founding the school. In his 1843 address to the General Assembly, the governor stated:

During the present year Mr. and Mrs. Willard, themselves mutes, and recommended as highly competent teachers, have opened an institution in Indianapolis for the instruction of the deaf and dumb. They had now thirteen pupils under their care . . . Mr. and Mrs. Willard are at present teaching without any compensation, for the purpose of shewing [sic] what may be accomplished in the instruction of those who are denied hearing and speech . . . I cannot however let his occasion pass without asking on their behalf that the legislature will make suitable provision for this institution . . .

By 1845, after it was incorporated as a state institution, Eliza was no longer listed as “matron.” Census records imply she then stayed “at home” as opposed to working.

[3] Indiana General Assembly, “An Act to Establish an Asylum for the Education of Deaf and Dumb Persons in the State of Indiana, approved January 15, 1844; First Annual Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the Legislature of the State of Indiana, for the Year 1844, Doc. No. 9 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1844), 136-140, accessed Archive.org; Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the General Assembly, December 1844, Doc. No. 10 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1844), 85-95, accessed Archive.org; James Whitcomb, “Governor’s Message,” December 3, 1844 published in Evansville Weekly Journal, December 12, 1844, 3, accessed Newspapers.com;

On January 15, 1844, the Indiana General Assembly made the school a state institution named the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb.

[4] The Indiana Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, Sixty-Third Annual Report of the Trustees and the Superintendent for the Fiscal Year Ending October 31, 1906 to the Governor (Indianapolis: Wm. M. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1907), accessed GoogleBooks; The Indiana State School for the Deaf, Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Trustees and the Superintendent for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1907 to the Governor (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1908, accessed GoogleBooks.

In 1907 the Indiana General Assembly changed the name from the Indiana Asylum for the Deaf and Dumb to the Indiana State School for the Deaf. In their 1907 report, school leaders wrote about the importance of this name change:

The new law also changed the name of the Institution to The Indiana State School for the Deaf, and specifically provided that it should not be regarded nor classed as a benevolent or charitable institution but as an educational institution of the State, conducted wholly as such. This we believe to be one of the most important acts of the last legislature . . . Thus gives the school its proper place in our educational system. The pupils are not criminals, they are not insane, they are not incorrigible, they are not mental or moral defectives, they are not homeless, they are not objects of charity; they are simply students, and as such should not be obliged to pass under an assumed name for the purpose of securing that which is their right, an education, and which the state owes them as a matter of right.

[5] “Deaf and Dumb Asylum,” Indiana State Sentinel, December 2, 1846, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “The City of Indianapolis – No. XIV,” (Indianapolis) Locomotive, August 19, 1848, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Steward’s Report” in Report of the Trustees and Principal of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb with an Exhibit of Expenditures, Presented to the General Assembly, December 6, 1847 (Indianapolis: John D. Defrees, State Printer, 1847), 41, accessed GoogleBooks; “Deaf & Dumb Asylum Near Indianapolis,” Indiana State Sentinel, July 19, 1849, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Indiana Deaf and Dumb Asylum,” Indiana State Sentinel, August 8, 1850, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Superintendent’s Report,” in Seventh Annual Report of the Trustees and Superintendent of the Indiana Asylum for Educating the Deaf and Dumb to the General Assembly 1850, Doc. No. 4 (Indianapolis: J.P. Chapman, State Printer, 1851), 231, accessed Archive.org; Windell W. Fewell, “A History of the Indiana State School for the Deaf,” Master’s Thesis, Butler University, 1949, pp. 20-26, accessed Butler University Digital Commons.

After occupying two previous locations in Indianapolis and outgrowing their facilities with increased enrollment, the Indiana General Assembly purchased extensive grounds at State and Washington Streets (National Road) about a mile from downtown in 1846. (The school’s enrollment had grown to 125 students by 1850). The new buildings on East Washington Street opened to students in October 2, 1850. For in-depth description of the buildings and facilities as well as architect plans see Windell W. Fewell’s “A History of the Indiana State School for the Deaf.”

[6] Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb to the General Assembly, December 1845 (Indianapolis: J.P. Chapman, State Printer, 1845), Doc. No. 10, Part II, n.p. (p. 87), accessed GoogleBooks; “Principal’s Report,” in Report of the Trustees and Principal of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb with an Exhibit of Expenditures, Presented to the General Assembly December 6, 1847 (Indianapolis: John D. Defrees, State Printer, 1847, Doc. No. 1, Part II, p. 35, accessed Google BookS; 1860 United States Federal Census, Schedule 1, Center Township, , Marion County, Indiana, June 1, 1860, Roll M653_280, Page 746, Lines 9-10, accessed AncestryLibrary; 1870 United States Federal Census, Schedule 1, Ward 9, Subdivision 20, Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana, February 10, 1870, Roll M593_339, Page 581B, Lines 9-15, accessed AncestryLibrary.

William served as the school’s first principal and then as an assistant principal and instructor into the 1860s. He was replaced as principal (position changed to superintendent) by James Brown, a hearing person, in 1845. The 1847 report stated:

It had been contemplated from the first, to ultimately appoint a Principal who could hear, and speak. This intention was carried out, in June 1845, by the appointment of the undersigned, his duties to commence on the 1st of August following. The highly Valued services of Mr. Willard, were continued in the capacity of an Assistant.

[7] Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the General Assembly, December, 1846 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1846), Doc. No. 9, Part II, 99-103; Eighth Annual Report of the Trustees and Superintendent of the Indiana Asylum for Educating the Deaf and Dumb to the General Assembly 1851 (Indianapolis: J.P. Chapman, State Printer, 1851), Doc. 4, Part II, 169-170;

Eleventh Annual Report of the Trustees and Superintendent of the Indiana Institution for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb 1854 to the Legislature (Indianapolis: Austin H. Brown, State Printer, 1855), Doc. No. 1, Part II, 570-4, 585; “Learning a Trade,” Indiana Deaf-Mute Journal, November 28, 1887, 1, Indiana School for the Deaf Collection, IUPUI University Library, accessed http://www.ulib.iupui.edu/collections/ISD; Fewell 76-77.

By 1850, the school aimed for both academic education and practical training for its students to give them the best opportunities for employment after graduation. The students had ample opportunity to show off their education through public demonstrations as well as presentations to the General Assembly and other schools during the early years of the institution. In 1851, the Trustee’s Report to the Governor stated: We have reference to the erection of substantial shop-buildings, for the purpose of carrying on various branches of mechanical trades . . . We are entirely satisfied that the education of a mute is greatly deficient, if it does not include a practical knowledge of some branch of business, ordinarily followed for a livelihood.

The school included an Intellectual and Domestic department and, in 1854, added a Mechanical Department, later called the Industrial Department. It included a copper shop, shoe shop, and garden. Female students learned tailoring and needlework. The Trustees reported: “The policy of the Board has been, as it will continue to be, to make the mental and moral education of the mutes, and their instruction in useful trades, the great and leasing features of the Institution.” The financial reports of the institution, included in the annual report to the governor, show that sales from the student industrial production brought some profit to the school to offset costs. In 1887, the school added a print shop and the students began printing a newspaper called the Indiana Deaf-Mute Journal, which became the Silent Hoosier in 1889. Interestingly, an article in their first issue advocated for the importance of learning a trade. By 1893, the course of study was divided into Primary (grades 1-5), Intermediate (equivalent to middle school today), and Academic (equivalent to high school today), as well as the industrial department, which by this point also included printmaking, drawing, and design, among other trades. The courses have continued to change over the years. By 1942, the courses given at the School for the Deaf reflected those of most Indiana schools.

[8] William Willard, “Speech of Deaf and Dumb,” Indiana State Sentinel, October 3, 1843, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Phineas D. Gurley, “Report” in Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the General Assembly, December, 1846 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1846), Doc. No. 9, Part II, 99-103; James S. Brown, “Principal’s Report” in Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb with an Exhibition of Expenditures, Presented to the Indiana General Assembly, December 6, 1847 (Indianapolis: John D. Defrees, State Printer, 1847), Doc. No. 1, Part II, 13-36; Fewell, 72-73; Twenty-fifth Annual Report of the Indiana Institution for Educating the Deaf and Dumb (Indianapolis: State Printer, 1869), 21, in Fewell, 89; “Which Is It? Some Pertinent Questions Concerning the Education of Deaf-Mutes,” Indiana Deaf-Mute Journal, December 12, 1887, 2, IUPUI University Library, accessed http://ulib.iupuidigital.org/cdm/compoundobject/collection/ISD/id/9/rec/2; Indiana School for the Deaf, “Bilingual Education,” accessed https://www.deafhoosiers.com/resources

William Willard advocated for teaching sign language as opposed to oral communication. Willard wrote in 1843: “As a general rule it is rather labor lost to attempt to teach a deaf and dumb person to speak orally, as the sign language, in an extended sense, is more sure, perspicuous and expeditious, if not more pleasant.” An examination of board reports shows that signing was the main form of communication and instruction through the early years of the school. Board President Phineas Gurley reported on student progress in 1846: “The rapidity with which they learn to communicate and receive ideas by means of the language of signs would exceed belief, if it had not already become a matter of practical demonstration . . .” Principle James S. Brown agreed, writing in 1847, “The process of instruction in this, as in all American Asylums, is principally carried on by means of signs used as representatives of the ideas usually conveyed by vocal sounds.” However, the school later offered instruction in both methods. In 1868, the board recommended in their report that “more special instruction should be given in articulation and reading from the lips, to such of the pupils and could be benefited by such training.” While signing remained the primary method of instruction, by the 1890s, regular articulation classes were held and the school board advocated for the “combined method” of manual, oral, and aural instruction. A search of the student newspapers shows the evolution of the discussion over the different methods. For example, in 1887 students argued for sign language over other methods and specifically for the use of the manual alphabet as superior to gesture signs. They felt that gestures were complex and took years to memorize, while anyone could learn the manual alphabet in an hour.

By the 1940s, mechanical hearing aids were also introduced for some students. Today, the Indiana School for the Deaf offers a bilingual education with instruction in both American Sign Language and English.

[9] Indiana General Assembly, “An Act to Establish an Asylum for the Education of Deaf and Dumb Persons in the State of Indiana, approved January 15, 1844; First Annual Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the Legislature of the State of Indiana, for the Year 1844, Doc. No. 9 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1844), 136-140, accessed Archive.org; Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the General Assembly, December 1844, Doc. No. 10 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1844), 85-95, accessed Archive.org; James Whitcomb, “Governor’s Message,” December 3, 1844 published in Evansville Weekly Journal, December 12, 1844, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; Article IX – Institutions, Section 1 (Amended 1984), Indiana Constitution of 1851, accessed Indiana Historical Bureau, https://www.in.gov/history/2473.htm.

When the Indiana General Assembly made the school a state institution on January 15, 1844 (see footnote 3), it levied a tax that covered board and tuition for all Hoosier students. Out of state students were accepted but paid tuition and board. When the General Assembly approved the new Indiana State Constitution in 1852, the tax assessment was replaced by direct funding from the treasure.

[10] First Annual Report of the Trustees of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb, to the Legislature of the State of Indiana, for the Year 1844, Doc. No. 9 (Indianapolis: J. P. Chapman, State Printer, 1844), 136-140, accessed Archive.org; James S. Brown, “Principal’s Report,” in Report of the Trustees and Principal of the Indiana Asylum for the Education of the Deaf and Dumb with an Exhibit of Expenditures Presented to the General Assembly December 6, 1847 (Indianapolis: John D. Defrees, State Printer, 1847), Doc. No. 1, Part II, 13-36.

While often paternalistic or patronizing in tone and word choice, early board reports show that the trustees and instructors studied the ways in which the world of math, science, and literature, among other subjects opened to the deaf students through education. As early as 1844, the board reported:

Experience has abundantly shown that, though deprived of speech and hearing, their minds can be approached through other avenues by the lights of knowledge, and they can be thereby qualified for stations of usefulness and the highest rational enjoyments. Indeed the difference between the uneducated and the educated mute is almost incredible. There former ‘wends his weary way’ through life in ignorance and obscurity . . . but the latter, gladdened by the genial ray of knowledge. And fitted for the discharge of duty, becomes a blessing to his friends and to society . . . enjoys the present, and looks forward to the future with cheerfulness and hope.

Because some students arrived with only whatever signs they came up with to communicate at a basic level with their families, many underwent a rapid transformation at the school. In his 1847 report to the governor, Principal James S. Brown described in detail the progression of students from basic standard signing to complex concepts to reading and writing. Brown reported that the students then go on to study geography, arithmetic, history, religion, grammar, botany, natural history, philosophy, astronomy, and chemistry which “are learned with as much precision by them as any students.” He concluded, “As to intellectual development, there is perhaps not a case in the wide field of mind, where more improvement in made in a limited time,” than by the deaf students.

[11] Indiana Institution for Educating the Deaf and Dumb, Sixty-Second Annual Report of the Trustees and the Superintendent for the Fiscal Year Ending October 31, 1905 to the Governor (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1906), 24-25, accessed GoogleBooks; “Report of the Board of Trustees,” in Indiana State School for the Deaf, Sixty-Seventh Annual Report for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1910, (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1911), 11-13, accessed GoogleBooks; Indiana State School for the Deaf, Sixty-Eighth Annual Report for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1911 to the Governor (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1912, accessed GoogleBooks; “The New Institution,” in Indiana State School for the Deaf, Sixty-Ninth Annual report for the Fiscal Year Ending September 20, 1912 to the Governor (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1913), 21-24, accessed GoogleBooks; Fewell 26-31.

The general assembly created a new building commission in 1903. The State of Indiana purchased a new 76.96 acre site north of the State Fairgrounds on May 12, 1905. The opening of the 1911-1912 school year was delayed by construction. Thus, the new building opened to students October 11, 1911. It was dedicated June 9, 1912 by the board, alumni, and Governor Thomas Marshall among others.

[12] “Willard Park Is Suggested,” Indianapolis Star, May 6, 1905, 14, accessed Newspapers.com; “Willard Park the Name,” Indianapolis News, May 29, 1908, 7, accessed Newspapers.com; Indiana State School for the Deaf, Sixty-Fifth Annual Report of the Trustees and the Superintendent for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1908 to the Governor (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1909), 30, accessed GoogleBooks; “Razing Building that Played Prominent Part in Early Educational Efforts of State,” Indianapolis News, June 22, 1912, 3, accessed Newspapers.com; “Entertainment for Benefit of Fund,” Indianapolis Star, July 11, 1912, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “The Star Summer Mission Fund,” Indianapolis Star, August 25, 1912, 22, accessed Newspapers.com; “Willard Park Lawn Fete to Assist Mission Work,” Indianapolis Star, September 11, 1912, 13, accessed Newspapers.com; “The New Institution,” in Indiana State School for the Deaf, Sixty-Ninth Annual report for the Fiscal Year Ending September 20, 1912 to the Governor (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1913), 21-24, accessed GoogleBooks;

The state sold the grounds to the city in 1904, but the school did not relocate until 1911 (see footnote 12). In 1908 the Indiana Association of the Deaf adopted this resolution:

Resolved. That we thank the Honorable Charles A. Bookwalter, Mayor of Indianapolis, for his attendance at our opening session and the Board of Public Parks for their action in naming these old beloved grounds of ours Willard Park in memory of the founder of our school.

By 1912, newspapers show the park was being used by the public for events and recreation.