Location: Stateline Ball Park / Town Grove, near 305 Church St. in West College Corner (Union County, Indiana) 47003

Installed 2017 Indiana Historical Bureau and the Society of Former Special Agents of the FBI

ID#: 81.2017.1

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn more about about the incident.

Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn more about about the incident.

Text

Side One:

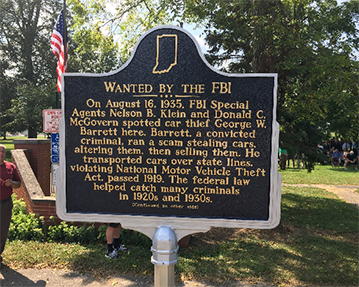

Wanted by the FBI

On August 16, 1935, FBI Special Agents Nelson B. Klein and Donald C. McGovern spotted car thief George W. Barrett here. Barrett, a convicted criminal, ran a scam stealing cars, altering them, then selling them. He transported cars over state lines, violating National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, passed 1919. The federal law helped catch many criminals in 1920s and 1930s.

Side Two:

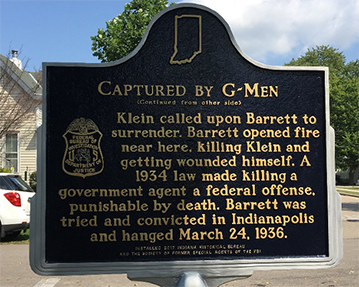

Captured by G-Men

[image of FBI badge]

Klein called upon Barrett to surrender. Barrett opened fire near here, killing Klein and getting wounded himself. A 1934 law made killing a government agent a federal offense, punishable by death. Barrett was tried and convicted in Indianapolis and hanged March 24, 1936.

Annotated Text

Side One:

Wanted by the FBI[1]

On August 16, 1935, FBI Special Agents Nelson B. Klein and Donald C. McGovern spotted car thief George W. Barrett here.[2] Barrett, a convicted criminal,[3] ran a scam stealing cars, altering them, then selling them.[4] He transported cars over state lines, violating National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, passed 1919.[5] The federal law helped catch many criminals in 1920s and 1930s.[6]

Side Two:

Captured by G-Men[7]

[image of FBI badge]

Klein called upon Barrett to surrender. Barrett opened fire near here, killing Klein and getting wounded himself.[8] A 1934 law made killing a government agent a federal offense, punishable by death.[9] Barrett was tried and convicted in Indianapolis[10] and hanged March 24, 1936.[11]

Note: All newspaper articles were accessed via Newspapers.com unless otherwise noted.

For more information about this topic, including biographies of FBI Special Agent Nelson B. Klein and George W. Barrett, contextual information regarding the early history and development of the FBI, and court testimony and records on the 1935 case, see William E. Plunkett, The G-Man and the Diamond King: A True FBI Crime Story of the 1930s (Wilmington, OH: Orange Frazier Press, 2015).

[1] For information on the history of the FBI, see “A Brief History,” accessed FBI.gov/history, and “History - Federal Bureau of Investigation,” accessed FAS.org, https://fas.org/irp/agency/doj/fbi/fbi_hist.htm.

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) traces its history back to 1908 when Attorney General Charles Bonaparte established a force of Special Agents during President Theodore Roosevelt’s tenure. In 1909, the force was organized under the name the Bureau of Investigation (BOI). During its early history, it was often referred to as the Bureau of Investigation or the Division of Investigation. The name officially changed to the Federal Bureau of Investigation in 1935. The term FBI and the badge featured on side two of the historical marker is used instead of the BOI for consistency and recognition, and because Special Agent Klein was killed after the organization’s name had already changed.

[2] “Death Penalty Request in U.S. Agent’s Slaying,” Cincinnati Times-Star, August 17, 1935, 1, 20, submitted by applicant; “Barrett Held, Shot by Wounded Officer,” [Hamilton, Ohio] Journal News, August 17, 1935; “Nelson Klein Fatally Shot in Gun Fight at College Corner,” Cincinnati Post, August 17, 1935, submitted by applicant; “Lockland Suspect Hit by Bullets of Agents Seeking Him in Thefts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 17, 1935, submitted by applicant; “Barrett v. United States, 1936, Circuit Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, no. 5718, accessed Justia; “FBI Cincinnati History,” accessed FBI.gov/history.

For information on Special Agent Nelson B. Klein and his career with the FBI, see his biography, accessible through the FBI’s Hall of Honor at https://www.fbi.gov/history/hall-of-honor and William E. Plunkett, The G-Man and the Diamond King: A True FBI Crime Story of the 1930s.

In August 1935, Special Agents Nelson Klein and Donald McGovern from the Cincinnati office of the Division of Investigation began investigating George Barrett for his suspected involvement in a number of motor vehicle thefts. (See footnote 4 for details on Barrett’s schemes in Ohio and across the country). According to court testimony in Barrett v. United States, heard in the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals on March 17, 1936, Klein and McGovern learned that Barrett was in Hamilton, Ohio after a recent car deal, but neither they nor the local police managed to question or arrest him before he left the area. Acting on a tip, the Special Agents suspected Barrett might travel to College Corner at the Ohio-Indiana border, where Barrett’s brother lived, and drove there on August 16, 1935.

Newspaper articles in the Cincinnati Enquirer, Cincinnati Times-Star, and [Hamilton, Ohio] Journal News, as well as the FBI’s overview of the Cincinnati field office’s history, all report that Klein and McGovern “spotted” Barrett near the residence of his brother’s home in College Corner, along with a vehicle matching the motor number of an automobile involved in one of Barrett’s recent schemes. According to court records and the publications referenced above, Klein immediately telephoned the sheriff’s office in Hamilton for assistance in arresting Barrett and he and McGovern parked their car and waited. Before Sheriff John Schumacher and Deputy Charles Walke arrived, Barrett returned to his car with a package in hand. This package, it was later learned, was a gun wrapped inside a towel. According to court records:

As he [Barrett] started to unlock the car door, McGovern and Klein started their car, turned and drove to Barrett’s car thinking he was attempting to escape them. Barrett turned from his car and started rapidly up a nearby alley toward a tree.

Klein jumped out of his vehicle and called out to Barrett to get him to stop. Barrett proceeded to open fire against the Special Agent. (See footnote 8 for information on the gun battle that ensued, in which Barrett shot and killed Special Agent Klein).

[3] “George W. Barrett,” Indiana Death Certificates, 1899-2011, Indiana Archives and Records Administration, 1936, roll 4, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Death Penalty Request in U.S. Agent’s Slaying,” Cincinnati Times-Star, August 17, 1935, 1, 20, submitted by applicant; “Shot Mother in Kentucky, Barrett Says; Federal Man on Guard at Hospital,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 17, 1935; "Kentuckian Faces Trial for Killing Government Man," The Tennessean, December 2, 1935; “U.S. Evidence Piled Higher in Barrett Case,” Indianapolis Star, December 4, 1935, 1-3; "Jurors Ready to Weigh Charge Against George Barrett in Klein's Slaying," Cincinnati Enquirer, December 7, 1935; “Noose Verdict is First Under New U.S. Law,” Indianapolis Star, December 8, 1935, 1-2; William E. Plunkett, The G-Man and the Diamond King: A True FBI Crime Story of the 1930s (Wilmington, OH: Orange Frazier Press, 2015).

For information on Barrett’s violations of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, see footnote 4.

Barrett’s death certificate states that he was born in Kentucky in 1887. According to former Special Agent William Plunkett, Barrett grew up in the foothills of the Cumberland Mountains in Clay County, Kentucky and began mastering the use of rifles at an early age. He enlisted in the U.S. Army in the early 1900s, where he reportedly became a qualified marksman. Plunkett reports that after his army service, Barrett entered the business of making and selling bootleg whiskey. Internal Revenue agents learned that he was selling liquor without a license and obtained a warrant for his arrest. In 1913, Deputy U.S. Marshals arrested Barrett, who pled guilty to the crime and was sentenced to thirty days in the Jefferson County Jail in Louisville. Plunkett notes that Barrett was also indicted on “obstructing, resisting and opposing a United States marshal in the performance of his duty.” Barrett’s criminal activity was just beginning. Plunkett states, “No lesson was learned by Barrett, and in his own words, he ‘came out of prison a wiser and more cunning criminal that I had gone in.’”

According to Plunkett, Barrett later became involved in the fencing of stolen jewelry, eventually earning the nickname the “Diamond King,” because of the expensive stones he would carry with him. He also sold illegal firearms. Plunkett reports that in 1924 he was charged with “carrying a concealed weapon, violating immorality laws and fined one hundred and eighty dollars.”

In 1930, Barrett was involved in a family dispute and shot his mother and sister in Kentucky. His mother died from the incident and his sister, who was wounded, later died of pneumonia. The case was referenced during Barrett’s 1935 trial for killing FBI Special Agent Nelson B. Klein. According to the Cincinnati Enquirer, August 17, 1935, Barrett stated, "I shot my mother because my own life was in danger. . . I have never shot anyone unless it was to save my life." Plunkett notes that Barrett was tried twice on a murder charge for killing his mother, but was acquitted.

During Barrett’s 1935 court case for killing Special Agent Klein, newspapers noted that Barrett’s criminal record spanned over twenty years. In his arguments to the jury, District Attorney Val Nolan stated: “I say to you, George Barrett, that I think there are locked in your breast many undivulged crimes that have gone unwhipped of justice and that no other than the full penalty of the law will suffice in this case. No Kentucky cousin of yours is prosecuting this murder and you are facing a jury the like of which you never saw before.”

[4] “Death to be Sought,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 17, 1935, submitted by applicant; “Death Penalty Request in U.S. Agent’s Slaying,” Cincinnati Times-Star, August 17, 1935, 1, 20, submitted by applicant; “Slayer of Federal Officer in College Corner Battle May Face Trial in Indiana,” [Richmond] Palladium Item, August 17, 1935; “Accused Slayer is Linked with Car Theft Ring,” Richmond Item, August 23, 1935; “Auto Recovered, Barrett Accused,” [Hamilton, Ohio] Journal News, August 26, 1935; Barrett v. United States, 1936, Circuit Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, no. 5718, accessed Justia at http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/82/528/1500579/.

Newspaper articles published in Cincinnati and Indiana in August and December 1935 report that the Department of Justice had Barrett under surveillance since 1931 for dealing in stolen automobiles. In Barrett v. United States, in the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals, heard on March 17, 1936, the court confirmed these reports and provided details on Barrett’s criminal activities, stating:

His method was to buy an automobile, obtain title papers for it, steal an automobile of similar description, change its motor numbers to correspond with those on the purchased car, obtain duplicate title papers, and then sell the stolen car to some dealer.

In each instance, Barrett sold the stolen vehicles with papers purporting to show that the sales were legitimate. According to the court, Barrett rented a vehicle in San Diego in 1934 under the alias of George W. Ball, drove this vehicle to Kentucky, changed its motor numbers, and then sold it. The following year, Barrett rented a vehicle in St. Louis, drove this vehicle to Ohio, changed its motor numbers so they matched those on a new car he purchased through the Central Motor Company in Hamilton, Ohio, and sold it to the same car dealer, who in turn sold it to another gentleman in early August 1935. The manager for the Central Motor Company came to realize that both cars – the one that his company sold to Barrett and the other that Barrett had sold to them and that was in turn sold to another individual – had the same motor numbers. FBI Special Agents Nelson Klein and Donald McGovern of the Cincinnati office of the Division of Investigation began investigating Barrett’s dealings in stolen motor vehicles at this time. In the days that followed, they traced many vehicles that Barrett had stolen to Hamilton, Ohio.

The Cincinnati Enquirer, Cincinnati Times-Star, and Palladium Item, among many other newspapers, reported on these stolen vehicles in the days following FBI Special Agent Klein’s death. The stolen vehicles linked Barrett to crimes in Ohio and in other states throughout the country where he had used this scheme of changing motor numbers to make a profit on stolen vehicles.

[5] “Dyer’s Bill Would Lessen Car Thefts,” Washington Times, September 11, 1919; “House Enacts Law to End Traffic in Stolen Motor Cars,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 17, 1919; “Senate Will Consider Motor Theft Measure,” Indianapolis News, September 22, 1919; “National Motor Theft Law Operative,” Motor Age 36, no. 18 (October 30, 1919): 12-13, accessed Google Books; “Motor Theft Law is Now in Effect,” Washington Times, November 1, 1919; “Here’s the New Federal Law Against Auto Thievery,” Washington Times, November 29, 1919; “Transportation of Stolen Vehicles,” Title 18─Crimes and Criminal Procedure, Chapter 113, Section 2312, accessed Justia.com, http://law.justia.com/codes/us/2014/title-18/part-i/chapter-113/sec.-2312/.

In 1919, Congressman L.C. Dyer of Missouri introduced a bill to supplement individual states' efforts to combat automobile theft. The Brooklyn Daily Eagle and Indianapolis News reported in September 1919 that the practice of stealing automobiles was on the rise throughout the country, especially in some Midwest cities such as Detroit, Chicago, and St. Louis. According to the News, over 22,000 automobiles were reported stolen in eighteen western and midwestern cities in 1918. An October 1919 article in Motor Age magazine put the number at 29,399 in twenty-one cities. Representative Dyer argued that the losses amounted to hundreds of thousands of dollars each year, while also causing hefty increases in automobile theft insurance.

The House of Representatives passed Dyer's bill in mid-September by a vote of 200-40. The Senate approved it soon after and President Wilson received it October 17, 1919. After not signing or returning it to Congress within the prescribed amount of time, the bill became a law. Known as the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, or Dyer Act, it sought "to punish the transportation of stolen motor vehicles in interstate or foreign commerce." In accordance with the law, anyone who knowingly transported or caused to be transported a stolen motor vehicle in interstate or foreign commerce could be fined up to $5,000, imprisoned for up to five years, or both. Those found guilty of violating the law could be punished in any district through which the guilty party transported the vehicle.

For details on the act and its specific language, see “Transportation of Stolen Vehicles,” Title 18─Crimes and Criminal Procedure (cited above) and "Here's the New Federal Law Against Auto Thievery," Washington Times, November 29, 1919. For more on the importance of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, particularly its impact on the FBI during the 1920s and 1930s, see footnote 6.

[6] “National Motor Theft Law Operative,” Motor Age 36, no. 18 (October 30, 1919): 12-13, accessed Google Books; “Indict 5 in Big Plot to Steal City Autos,” New York Times, July 27, 1920; “Uncle Sam Goes After an Alleged Automobile Thief,” Oregon Daily Journal, December 6, 1921; “Louisville Man Held for Vehicle Act Violation,” Indianapolis Star, February 19, 1922; “Justice Department Men Put on Dillinger’s Trail,” Indianapolis Star, March 7, 1934; “Durkin – Murder of an FBI Agent,” Famous Cases & Criminals, FBI.gov/history; “John Dillinger,” Famous Cases & Criminals, FBI.gov/history.

According to former Special Agent William Plunkett in The G-Man and the Diamond King, “the BOI gained more influence in 1919 with the passage of the Dyer Act . . . now it could prosecute criminals who’d previously evaded the Bureau by driving across a state line. More than any other law, the Dyer Act sealed the FBI’s reputation as a national investigative crime-fighting organization.”

In the early 1900s, law enforcement officials struggled to combat a significant rise in national crime. The BOI (later FBI) was still in its infancy and local police forces lacked the guns, technology, and training to stop the crime wave. The affordability and accessibility of motor vehicles at this time gave criminals more opportunities to evade capture. Prohibition also contributed to the crime wave as bootlegging became popular and profits obtained from illegal activities spurred further offenses. According to the FBI, “dealing with bootlegging and speakeasies was challenging enough, but the ‘Roaring Twenties’ also saw bank robbery, kidnapping, auto theft, gambling, and drug trafficking become increasingly common crimes.”

In many instances, law enforcement officials were powerless against these criminals. The National Motor Vehicle Theft Act helped expand the role and power of the FBI by providing federal agents with a reason for pursuing many of these men and women at the federal level. According to a 1919 Motor Age article issued soon after the passage of the act:

Many of the states already have motor vehicle theft laws. But the thieves soon learned how to circumvent these laws. They learned that the Federal Government had no such law and that when once an automobile was taken across a state line it was almost impossible to recover the car, prosecute the thief or summon the purchaser as a witness.

Newspapers published numerous articles on violations of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act soon after the law went into effect, with federal officers arresting many professional automobile thieves in the 1920s and 1930s. In many instances, these criminals were wanted for other offenses, including murder. Prior to the passage of the act, federal agents did not have the authority to pursue such criminals and had to let local and state authorities try to handle the rising number of cases. In some instances, local authorities caught and successfully imprisoned criminals and gangsters of the period, only to see their prison sentences expire or have them escape and commit more dangerous crimes. This was particularly true in the case of notorious gangster John Dillinger. In the early 1930s, Dillinger and his gang robbed several banks, plundered police arsenals, killed a police detective in Chicago, and fled the county jail in Crown Point, Indiana in March 1934 after being held to await trial. The FBI’s website states:

It was then that Dillinger made the mistake that would cost him his life. He stole the sheriff’s car and drove across the Indiana-Illinois line, heading for Chicago. By doing that, he violated the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, which made it a federal offense to transport a stolen motor vehicle across a state line.

After Dillinger violated the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act, the FBI became actively involved in his capture. On March 7, 1934, the Indianapolis Star reported, “. . . the reported theft of an automobile by Dillinger, used to get out of the state of Indiana, gave the [Department of Justice] jurisdiction under provisions of the national motor vehicle theft act.” For more information on Dillinger’s case, see “John Dillinger,” Famous Cases & Criminals, FBI.gov/history and “Dillinger Inventory,” Indiana Archives and Records Administration, accessed http://www.in.gov/iara/2839.htm.

[7] “They’re to be FBI-Men Now,” Akron [Ohio] Beacon Journal, July 4, 1935; “Shot Mother in Kentucky, Barrett Says; Federal Man on Guard at Hospital,” Cincinnati [Ohio] Enquirer, August 17, 1935; “Nelson B. Klein, G-Man, Wounds Desperado in Both Legs but Dies in Gun Battle,” Sheboygan [Wisconsin] Press, August 17, 1935; “The FBI and the Gangster, 1924-1938,” A Brief History, FBI.gov/history; ’G’ Men, Directed by William Keighley, Warner Bros., 1935, accessed http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0026393/.

According to the FBI’s website, “before 1934, ‘G-Man’ was underworld slang for any and all government agents. . . By 1935, though, only one kind of government employee was known by that name, the special agents of the Bureau.” The term “G-Men” appeared frequently in newspaper articles about the federal agents working under J. Edgar Hoover and the term took root in the public’s mind. In 1935, during the height of the gangster film era, Warner Bros. released a movie entitled ‘G’ Men starring James Cagney, Margaret Lindsay, and Ann Dvorak.

Articles reporting on FBI Special Agent Klein’s death often used the term in reference to Special Agents Klein and McGovern.

[8] “U.S. to Push Charges in Slaying of G-Man,” Cincinnati Post, August 17, 1935, 1-2, submitted by applicant; “Death Penalty Request in U.S. Agent’s Slaying,” Cincinnati Times-Star, August 17, 1935, 1, 20, submitted by applicant; “Slayer of Federal Officer in College Corner Battle May Face Trial in Indiana,” [Richmond] Palladium-Item, August 17, 1935; “Lockland Suspect Hit by Bullets of Agents Seeking Him in Thefts,” Cincinnati Enquirer, August 17, 1935, 1, 15, submitted by applicant; “U.S. Evidence Piled Higher in Barrett Case,” Indianapolis Star, December 4, 1935; Barrett v. United States, 1936, Circuit Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit, no. 5718, accessed Justia at http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/82/528/1500579/.

On August 17, 1935, one day after FBI Special Agent Klein’s passing, newspapers across the country began reporting on the gun battle that had ensued in College Corner, along the Ohio-Indiana border. The Cincinnati Times-Star and Cincinnati Enquirer, along with the [Richmond] Palladium-Item all stated that Barrett had opened fire on FBI Special Agent Klein first. According to the articles, after “spotting” Barrett beside a car, Klein called out that they were federal agents and began to pursue him, causing Barrett to flee. Klein reportedly followed him down an alley that led into an open yard, at which time Barrett began firing at him. Newspapers report that Klein drew his own gun after being struck and succeeded in hitting Barrett in the legs.

During the court case in December 1935, most witnesses confirmed these reports. These witnesses, as detailed in the Indianapolis Star on December 4, 1935, included Paul McDonough and his wife Agatha McDonough, along with Emma Murphy, in whose adjoining yards the battle occurred, as well as Lethonia Forbes, who was visiting the McDonough house during the incident. The McDonoughs and Mrs. Forbes all testified that minutes after the shooting they approached the wounded Barrett, who told them he had “shot a government man.” Paul McDonough stated that Barrett said “It was him or me.” Agatha McDonough, on the other hand, testified that Barrett told them Klein shot him first, but again confirmed the fact that Barrett suspected Klein to be a “government man.” Mrs. Forbes provided more detail about the events that transpired. According to her testimony, when asked why he shot Klein, whom he believed to be a “government man,” Barrett reported: “I was in trouble and they were after me.”

FBI Special Agent Donald McGovern testified that before the chase and gun battle ensued, Klein had jumped out of their car and called “Stop, we’re Federal officers.” Klein pursued Barrett when he did not stop. McGovern noted that he heard several shots soon after and heard Klein call out that he had been shot, at which point McGovern saw Barrett behind a nearby tree, gun in hand, and fired at him (Barrett). According to McGovern, Klein did not have his gun in hand at any time prior to the shooting.

Court records from March 17, 1936, in the case of Barrett v. United States, largely confirm the testimonies referenced above. The court reported:

We think there can be no question but that appellant at the time of the shooting not only had reasonable ground to believe, but actually knew, that Klein and McGovern were federal officers and were attempting to arrest him for a federal offense. The evidence discloses that appellant’s companion, shortly before the fatal encounter, notified appellant to this effect . . . In addition to this evidence, appellant in his signed confession said that he had been told at Hamilton on August 16, 1935, that federal men were laying traps for him . . .

The court continued:

A study of all the evidence convinces us beyond all reasonable doubt that appellant at the time of the shooting did not believe and had no reasonable ground to believe *532 that Klein and McGovern were Kentucky feudists seeking his life. We are further convinced from a perusal of the record that Barrett was the aggressor in the shooting.

[9] For newspaper coverage on the law, see: “Asks Law to Broaden Federal Fight on Crime,” [Columbus] Republic, January 5, 1934; “U.S. May Save Trial Expense in Dillinger Case,” [Muncie] Star Press, April 24, 1934; “Crime Bill Rushed by Committee,” Warren [Pennsylvania] Times Mirror, April 26, 1934; “Bill Passed Making Killing of U.S. Man a Federal Offense,” Wausau [Wisconsin] Daily Herald, May 5, 1934; “Odds Favor Dillinger Gangsters, Officials Say; They’re Better Equipped Than Federal Agents,” [Muncie] Star Press, May 6, 1934.

To read the law or criminal code, see: “An Act to Codify, Revise, and Amend the Penal Laws of the United States,” March 4, 1909, The Criminal Code of the United States as Amended During the Second Session Sixty-First Congress, Chapter 11, Sections 273-275 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1910): 1, 59-60, accessed Hathi Trust; “An Act to Provide Punishment for Killing or Assaulting Federal Officers,” May 18, 1934, The Statutes at Large of the United States of America from March 1933 to June 1934, 48, Part 1 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1934): 780-781, accessed Library of Congress; “An Act to Amend Act of May 18, 1934, Providing Punishment for Killing or Assaulting Federal Officers,” February 8, 1936, The Statutes at Large of the United States of America from January 1935 to June 1936, 49, Part 1 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1936): 1105, accessed Library of Congress; “Title 18─Crimes and Criminal Procedure,” June 25, 1948, Chapter 51, Sections 1111-1114, Pages 314-317, accessed Government Publishing Office.

In the spring of 1934, Congress voted on a series of bills intended to broaden the federal government’s fight against crime. These measures included efforts to regulate the traffic of machine guns and firearms, to prohibit interstate transportation of stolen property, and to make it a federal offense to kill a federal officer or to rob a bank, among many others. Newspaper articles in April and May of 1934 reported that John Dillinger’s recent escape in Wisconsin, which resulted in the death of federal agent W. Carter Baum, spurred Congress to act quickly on the anti-crime bills.

On April 26, 1934, the [Pennsylvania] Warren Times Mirror reported that despite the many crimes for which Dillinger was accused, the only federal charge against him was the transportation of a stolen vehicle over state lines, a violation of the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act (Dyer Act). While it was a federal offense to take a stolen car across state lines, killing a government agent was not yet a federal crime and those found guilty of doing so could only be tried under the laws of the state where the killing occurred.

On May 5, 1934, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a Senate-approved bill making the killing or assault of a United States officer while on duty a federal offense. The law was officially enacted on May 18, 1934. It included the killing of special agents of the Division of Investigation of the Department of Justice, among many other federal officers. The act was amended on February 8, 1936, to reflect the change in name from the Division of Investigation to the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The 1934 act noted that those found guilty of killing or assaulting a federal officer “shall be punished as provided under Section 275 of the Criminal Code.” Amended in 1909, the Criminal Code of the United States stated that “Every person guilty of murder in the first degree shall suffer death” (see Sections 273 and 274 of the Criminal Code for clarification on first degree and second degree murder). Section 330 of the code noted an exception:

In all cases where the accused is found guilty of the crime of murder in the first degree, or rape, the jury may qualify their verdict by adding thereto “without capital punishment;” and whenever the jury shall return a verdict qualified as aforesaid, the person convicted shall be sentenced to imprisonment for life.

See Title 18─Crimes and Criminal Procedure,” June 25, 1948, for more information.

[10] "Barrett Will be Tried Here for Slaying Klein," Indianapolis Star, August 18, 1935; "'G-Man' Killer to Stand Trial," Sandusky [Ohio] Register, August 18, 1935; "Alleged G-Man Slayer to Get Speedy Trial," Richmond Item, August 21, 1935; "Barrett at Indianapolis," Cincinnati Enquirer, August 22, 1935; "Auto Recovered, Barrett Accused," [Hamilton, Ohio] Journal News, August 26, 1935; "Jurors Indict Man in Killing of Gov't Agent," Richmond Item, August 31, 1935; "Kentuckian Faces Trial for Killing Government Man," The Tennessean, December 2, 1935; U.S. Demands Life of George Barrett for Killing of G-Man," [Lafayette] Journal and Courier, December 3, 1935; "G-Man was Mistaken for Feud Killer, Says Barrett," [Lafayette] Journal and Courier, December 6, 1935; "Jurors Ready to Weigh Charge Against George Barrett in Klein's Slaying," Cincinnati Enquirer, December 7, 1935; "Noose Verdict is First Under New U.S. Law," Indianapolis Star, December 8, 1935; "Barrett Sentenced to Hang March 24," Richmond Item, December 15, 1935.

On August 18, 1935, just two days after the shooting, the Indianapolis Star reported that Barrett would stand trial in Indianapolis and would be taken there as soon as his wounds allowed. Although College Corner falls right on the Indiana-Ohio line, agents confirmed that Klein had fallen dead on the Indiana side. On August 21, the Richmond Item noted that the Federal Grand Jury, originally scheduled to meet for its regular session on September 9, had been ordered to convene earlier on August 30 to investigate charges against Barrett. According to the article, "the trial, to be held in the Indianapolis Federal Courtroom, will be the first murder trial ever conducted in the Southern Indiana District Court."

Federal officers transferred Barrett from the Hamilton, Ohio hospital to the City Hospital in Indianapolis on August 21. On August 26, the [Hamilton] Journal News reported on the recovery of one of the automobiles Barrett reportedly stole and transported over state lines from San Diego to Hamilton. Barrett allegedly changed the motor and serial numbers of the car before selling it to a garage in Hamilton. Jurors wasted no time in indicting Barrett for the murder of Special Agent Klein and for violating the National Motor Vehicle Theft Act.

Barrett's trial began on December 2. According to The Tennessean, he was only the second man to be tried under the new law (1934) providing for capital punishment in the killing of a federal officer. In early December, the Journal and Courier reported that the federal government sought the harshest punishment possible for the accused – death by hanging. Edward Rice, defense counsel for Barrett, argued that Barrett had been warned days before Klein's killing that Kentucky outlaws were after him and might pose as officers. As such, Barrett maintained that he acted in self-defense out of fear for his life. However, during his time on the witness stand, Special Agent Donald McGovern testified that Klein called out to Barrett and clearly identified himself and McGovern as federal officers.

On December 8, the Indianapolis Star reported that the jury only took fifty minutes to return a guilty verdict. With no qualification calling for life imprisonment, Barrett was to be hanged. District Attorney Val Nolan stated "I think this is the greatest victory for law and order ever achieved in the state of Indiana."

See http://law.justia.com/cases/federal/appellate-courts/F2/82/528/1500579/ for information on Barrett’s appeal and the decision of the Circuit Court of Appeals, Seventh Circuit in the case of Barrett v. United States on March 17, 1936.

[11] "Kentuckian Faces Trial for Killing Government Man," The Tennessean, December 2, 1935; “George Barrett Sentenced to Hang March 24,” Richmond Item, December 15, 1935; “Gallows’ Shadow Preys on Barrett,” Indianapolis Star, March 2, 1936; “Quits His Wheel Chair in Wrath,” [Greenfield, Indiana] Daily Reporter, March 11, 1936; “Phil Hanna, Expert Hangman, to Officiate at Barrett Execution,” Indianapolis News, March 18, 1936; “Barrett Gallows to Arrive Sunday,” Indianapolis Star, March 19, 1936; “Slayer of U.S. Agent Hanged After He Discusses Execution,” Chicago Daily Tribune, March 24, 1936, submitted by applicant; “Murderer of G-Man is Hanged in Indiana,” New York Times, March 24, 1936, submitted by applicant; “Services Held for Barrett,” Indianapolis Star, March 25, 1936.

On December 2, 1935, an article in The Tennessean reported that several years earlier electrocution had replaced hanging in Indiana. However, because Barrett’s sentence would be carried out under federal law, U.S. criminal code specified death by hanging. According to the Richmond Item, the last legal hanging in Marion County was in 1886, almost fifty years earlier. The article noted that Judge Robert C. Baltzell had never before sentenced a man to death and did not take the act lightly. Barrett was sentenced to die before sunrise March 24, 1936.

By March 11, the [Greenfield] Daily Reporter reported that Barrett “had threatened to eat his glass eye, to cut his wrists with his spectacles, and to kill his jail keepers.” Judge Baltzell reportedly contacted Washington for additional help guarding him in his cell following the outburst.

On March 18, the Indianapolis News noted that Phil Hanna, an expert hangman, would lead the execution. The News reported that Hanna, known as the “Humane Hangman,” had participated in sixty-eight previous hangings in an interest to see them done correctly, without additional pain or suffering to the condemned. Barrett hanged at 12:02 am on March 24, 1936 in the Marion County jail yard, and was pronounced dead ten minutes later. According to newspaper articles published soon after, many people showed up to see the hanging.