Location: 110 E 16th St, Indianapolis (Marion County, Indiana) 46202

Installed 2015 Indiana Historical Bureau, David E. Steele, and Friends and Family of T. C. Steele

ID#:49.2015.2

Text

Side One

By 1886, artist T.C. Steele resided here on estate called Tinker or Talbott property. By 1887, he built a studio on the grounds and opened it to the public. He taught classes, exhibited work, and helped advance the quality of Midwestern art, notably as part of Society of Western Artists. He served as vice-president of Art Association of Indianapolis (established 1883).

Side Two

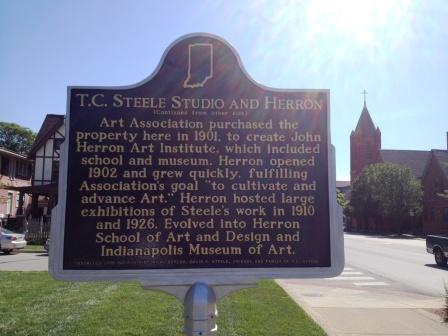

Art Association purchased the property here in 1901, to create John Herron Art Institute, which included school and museum. Herron opened 1902 and grew quickly, fulfilling Association’s goal “to cultivate and advance Art.” Herron hosted large exhibitions of Steele’s work in 1910 and 1926. Evolved into Herron School of Art and Design and Indianapolis Museum of Art.

Annotated Text

Side One

By 1886, artist T. C. Steele[1] resided here[2] on estate called Tinker/Talbott property.[3] By 1887, he built a studio on the grounds[4] and opened it to the public.[5] He taught classes,[6] exhibited work,[7] and helped advance the quality of Midwestern art,[8] notably as part of Society of Western Artists. [9] He served as vice-president of Art Association of Indianapolis[10] (established 1883).[11]

Side Two

Art Association purchased the property here in 1901[12] to create John Herron Art Institute,[13] which included school and museum.[14] Herron opened 1902[15] and grew quickly,[16] fulfilling Association’s goal “to cultivate and advance Art.”[17] Herron hosted large exhibitions of Steele’s work in 1910[18] and 1926.[19] Evolved into Herron School of Art and Design[20] and Indianapolis Museum of Art.[21]

Unless otherwise noted, T. C. Steele’s journal, letters, and speeches accessed: Theodore Clement Steele and Mary Lakin Steele Papers, 1869-1966, Collection No. M464, Indiana Historical Society. Items from this collection are cited: box number, folder number, and “Steele Papers.” Other letters are reproduced in: Selma N. Steele, Theodore L. Steele, and Wilbur Peat, House of the Singing Wind: The Life and Work of T.C. Steele (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society, 1966).

[1] 1850 United States Census (Schedule 1), District 84, Montgomery Township, Owen County, Indiana, Roll M432_164, page 21A, Line 11, September 5, 1850, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Swartz & Tedrowe’s Annual Indianapolis City Directory, 1874 (Indianapolis: Sentinel Company Printers, 1874), 357, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; S. E. Tilford & Co.’s Indianapolis City Directory, 1877 (Indianapolis: Publishing House Printers, 1877), 392, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; R. L. Polk & Co.’s Indianapolis Directory for 1879 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., 1879), 450, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Theodore C. Steele,” Passport Application, July 7, 1880, Publication M1372, Roll 0236, United States Passport Applications, 1795-1905, National Archives, accessed Fold3 by Ancestry.com; T.C. Steele, journal, circa 1869-1871, transcribed by Brandt Steele, Box 1, Folder 33, pp. 1, 5-7, 18-21, Steele Papers, Indiana Historical Society; “Art Etchings,” Indiana State Sentinel, April 12, 1876, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; T. C. Steele to James Whitcomb Riley, December 15, 1883, Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library Riley Collection, M0660, Box 2, Folder 6, accessed Indiana Historical Society Digital Collection.

Theodore Clement Steele, most often known as T. C. Steele, was born September 11, 1847 in Owen County, Indiana. According to Steele’s journal, he began his painting career by the 1860s, but felt he needed to study painting in Europe to advance his technique and career. Circa 1870, Steele wrote in his journal:

“It is now a settled plan of mine to visit Europe at the earliest possible period, and to spend two years study there. I am aware that difficulties are in my way that are great, but others possessing no more talent than I have, conquered them. And it is our part and portion here upon the earth to battle forever with difficulties. Especially is it so with him who adopts as his vocation, a profession that ministers to the taste of man rather than his appetites, to his feeling for the beautiful rather than that for utility. So let me put it down as a fixed determination to visit Europe the coming Summer.”

It took ten more years before Steele realized this dream. In 1880, he left Indianapolis, where he had been working as a portrait painter, to study at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Munich. He sent several works back to Indianapolis for exhibition and as payment to those sponsors who had paid for his schooling. For example, in 1883, he wrote to James Whitcomb Riley expressing his hope that Indianapolis art patron and dealer Herman Lieber would have success selling some of his paintings so he could continue his studies; he also requested news about an exhibition of his work. For more information on Steele’s time in Germany, see: Martin Krause, Return of Indiana Painters from Germany, 1880-1905 (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art and Wallraf-Richartz Museum, Cologne, in cooperation with Indiana University Press, 1991).

[2] "Indiana Artists," Indianapolis Sentinel, April 1, 1885, 4, accessed Chronicling America, Library of Congress; "News of the City," Indianapolis Evening Minute, May 15, 1885, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Art," Indianapolis Journal, June 14, 1885, 3, accessed ISL microfilm; "Fashion and Art," Fort Wayne World, July 4, 1885, 9, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; R. L. Polk & Co.’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1886 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., 1886), 671, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; May Wright Sewall, “The Art Association of Indianapolis: A Retrospect,” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 8, accessed Indiana State Library; “Annual Exhibitions” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 51, accessed Indiana State Library.

According to the Indianapolis Sentinel, by 1885, most Indianapolis residents knew Steele’s name. In May 1885, the Indianapolis Evening Minute reported upon his impending arrival and plan to open a studio downtown. The Indianapolis art community anticipated his return with an exhibition of work created by several Hoosiers who had been studying in Munich. The exhibition, Ye Hoosier Colony in Munchen, opened April 1, 1885. (See footnote 14 for more on the exhibition).

By June 1885, Steele had returned to Indianapolis. The Indianapolis Journal reported, “Mr. T. C. Steele is busy fitting up two elegant rooms in the Vance Block.” (See footnote 4 for more on his studio). The same month, the Indianapolis Art Association welcomed the artist home with a reception at the home of its president, Nathaniel A. Hyde. (See footnote 6 for information on the Association.) The Fort Wayne World reported, “Mr. T. C. Steele, a prominent artist of Indianapolis, has returned from Munich, after a five years' absence and his paintings are creating quite a stir in art circles.”

Secondary sources state that Steele and his family moved into the large house on the site known as the Tinker or Talbott property immediately upon their arrival in Indianapolis in 1885. (See footnote 3 for more information on the property.) However, the earliest primary source located by IHB researchers placing Steele on the site is the 1886 Indianapolis City Directory. Thus, while Steele had likely moved into the home at Seventh and Pennsylvania Avenues after this arrival in 1885, primary sources show he was definitely there by 1886.

[3] R. L. Polk & Co.’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1886 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., 1886), 671, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1887 Sanborn Maps of Indianapolis, Volume II, Plan 76, submitted by applicant; "The Artist Steele: A Visit to His Studio," Indianapolis News, February 19, 1887, 3, submitted by applicant; 1898 Sanborn Maps of Indianapolis, Volume II, Plan 221, submitted by applicant; "Mr. Steele's Art Collection," Indianapolis Journal, October 26, 1889, 5, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Artists' Suggestions," Indianapolis Journal, May 27, 1899, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Down Comes the 'Tinker Homestead,' A Landmark," Indianapolis Sun, June 17, 1899, 2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com.

The property at which Steele resided from circa 1886 until 1901 was bounded by Pennsylvania Avenue on the west, Talbott Avenue on the east, Hadley Street on the north, and Seventh Street on the south. By 1898, Hadley Street had been changed to Coram Street and Seventh Street to Sixteenth Street. When the Art Association purchased the property in 1901, Hadley Street was blocked off to conjoin the neighboring property. (See footnote 12 for more information).

During the 1880s and 1890s, newspapers mostly referred to the property by its location. For example the Indianapolis Journal reported in 1889 on a reception at “Mr. T. C. Steele’s studio, corner of Pennsylvania and Seventh Streets.” However, sometimes newspapers also referenced the home’s previous occupants, the Tinker and Talbot families. For example, the Indianapolis News reported in 1887, that Steele’s studio was "on Seventh Street, where the Pennsylvania street cars turn east and west, in the rear of the old Tinker mansion." In 1899, the Indianapolis Journal referred to it as "the Talbott place, at Pennsylvania and Sixteenth streets.” That same year, the Indianapolis Sun referred to the property as “the old 'Tinker homestead,' Pennsylvania and Sixteenth-sts.” During the negotiation of its purchase in 1900, newspapers mainly referred to the site as “the Talbott property,” but when it was torn down in 1905, the home was again referred to as “the old Tinker mansion.” (See the IHB marker file for other examples).

[4] "News of the City," Indianapolis Evening Minute, May 15, 1885, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Art," Indianapolis Journal, June 14, 1885, 3, Indiana State Library, microfilm; R. L. Polk & Co.'s Indianapolis City Directory for 1886, 671; "The Artist Steele: A Visit to His Studio," Indianapolis News, February 19, 1887, 3; 1887 Sanborn Maps of Indianapolis; Steele, House of the Singing Winds, 33, 35, 49-50.

When Steele first returned to Indianapolis in 1885, he rented a studio downtown on the Vance Block, just off Monument Circle. Indianapolis newspapers reported on the opening of this studio and the 1886 Indianapolis City Directory gave the address as 44 Vance Block. Reliable secondary sources, including House of the Singing Winds, claim that Steele built a studio on the Talbott property in 1886; however, no primary sources were located to support this date. Primary sources show that by February, 1887, he was working out of the studio, which the Indianapolis News described in a lengthy article. The newspaper reported:

“On Seventh street . . . in the rear of the old Tinker mansion, stands the studio of Mr. T. C. Steele, the artist. It is a modest little building erected for its purpose. . . Its northern windows look out upon a wide stretch of landscape, and, what is more to the purpose, afford unobstructed light from the north. Here the artist may be found, when not in the open air sketching, in all weathers, surrounded by his work. On entering one is struck by the number and variety of the pictures seen. . . Pictures hang upon the walls, recline on easels or rest upon the floor two or three deep, in profusion.”

The 1887 Sanborn Maps of Indianapolis show that the studio was located on the northeast corner of the property at the corner of Hadley Street and Talbott Avenue.

[5] "Art," Indianapolis Journal, June 14, 1885, 3, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "The Artist Steele: A Visit to His Studio," Indianapolis News, February 19, 1887, 3; "Mr. Steele's Art Collection," Indianapolis Journal, October 26, 1889, 5, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Inspiration from Vernon," Indianapolis Sun, October 22, 1891, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; T. C. Steele, “Studio Exhibit,” circa December 1895, Box 1, Folder 32, Steele Papers; "Swirl of Society," Indianapolis Sun, December 14, 1895, 6, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "An Exhibit of Pictures," Indianapolis Sun, December 18, 1897, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com.

While Steele also showed his work in formal exhibitions, locally and nationally, he often opened his studio to an interested public. As early as June 1885, the Indianapolis Journal reported that Steele was planning on opening his downtown studio to the public. The paper reported that although “his plans are not definite . . . after he gets to work he will have a day or two each week in which he will receive visitors." By 1887, he was working out of his home studio on the Tinker/Talbott property and soon also opened it to the public. In October 1889, Steele welcomed visitors for several days and displayed forty-five artworks, mostly his own with the addition of six watercolors by his friend and colleague, William Forsyth. The Indianapolis Journal reported that the exhibition "brought out a throng of that artist's admirers.” In 1891, the Indianapolis Sun reported that Steele and Forsyth spent a summer painting in Vernon, Indiana: "The fruits of their labor are now on exhibition at Mr. Steele's studio on the corner of Seventh and Pennsylvania sts."

T. C. Steele sent out invitations for an exhibition of thirty-seven of his works to be held Wednesday, December 11 through Sunday the 15 “at my studio, Talbott Place, N. E. Cor. 7th and Pennsylvania Sts.” (No year is listed, but the event must have occurred before the numbering system changed 7th Street to 16th Street in 1897. December 11 fell on a Wednesday in 1889 and 1895.) On December 14, 1895, the Indianapolis Sun noted that Steele would "continue his exhibit at his studio over Sunday," likely referencing the exhibition advertised by Steele in the invitation. In December 1897, the Indianapolis Sun reported that Steele was "now exhibiting at his studio, corner of Pennsylvania and Seventh-st., a number of good oils…” He continued this practice even after he left the Talbott property, including at his studio in Brown County and at Indiana University. (See House of the Singing Winds for more information on this later period. See pages 154-5 for a description of the public and students visiting his Brown County studio).

[6] Newspapers in this note accessed Hoosier State Chronicles unless otherwise noted: “News of the City,” Indianapolis Evening Minute,” May 15, 1885, 4, accessed newspaperarchive.com; "The Artist Steele: A Visit to His Studio," Indianapolis News, February 19, 1887, 3; T. C. Steele, The Development of the Connoisseur in Art, December 3, 1888, Box 2, Folder 1, Steele Papers; "Society Events," Indianapolis Journal, January 6, 1889, 3; "Educational," Indianapolis Journal, October 14, 1889, 3; "Educational," Indianapolis Journal, October 20, 1889, 10; "Commencement Notes," Indianapolis Journal, June 13, 1890, 5; "The Indiana School of Art," Indianapolis Journal, May 3, 1891, 16; "Indiana School of Art," Indianapolis Journal, May 13, 1891, 5; R. L. Polk & Co.'s Indianapolis City Directory for 1891 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., 1891) 728, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; "The Art School Exhibit," Indianapolis Journal, December 2, 1891, 5; "City Life," The (Indianapolis) Sun, May 19, 1892, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Among the Studios," Indianapolis Journal, March 11, 1894, 1; Steele, et al, The House of the Singing Winds, 6, 33, 34, 38-9.

Most Gilded Age American artists could not survive only on art sales and worked either as teachers or illustrators for the growing number of illustrated periodicals. While Steele mainly supported himself with commissioned portraits, he taught throughout his life, starting at a young age. According to The House of the Singing Winds, the 1865 catalogue for the Waveland Collegiate Institute listed Steele, age 18, as “the teacher of Drawing and Painting in the preparatory department.” When he returned from Munich, in 1885, he resumed teaching. According to the House of the Singing Winds, “In September, Steele and Miss Sue Ketcham, a respected teacher of art, launched their art school in the old Plymouth Church.” A note in the Indianapolis Evening Minute seems to confirm this: “T. C. Steele, the artist, will establish a studio in the old Plymouth church.” According to an 1887 Indianapolis News article, Steele also taught a large outdoor class in 1886.

On October 15, 1889, Steele opened his Indiana School of Art in downtown Indianapolis. (This school was not related to two earlier attempts at founding an art school of the same name). William Forsyth, also joined as an instructor. In June of 1890, the Indiana School of Art held its first student exhibition. In 1891, members of the Art Association of Indianapolis took control of the school. (See footnote 14 for more information.) While no longer serving as director, Steele continued to teach at the Indiana School of Art for several years. By 1894, however, he was no longer at the school, but instead teaching drawing technique at a downtown studio. By the end of 1894, however, Steele had gained national prominence as an artist and shortly thereafter ceased to teach formal classes, though he did serve as artist-in-residence at Indiana University later in life.

His dedication to educating Hoosiers on art continued outside of teaching in a formal classroom setting. Besides opening his studio to visitors (see footnote 5), Steele wrote and presented papers, especially on the topic of Midwestern art, throughout his career. For example, in 1888 he delivered “The Development of the Connoisseur in Art” to the Indiana Literary Club. According to the Indianapolis Journal, in 1889, he delivered the same lecture to the members of the Art Association of Indianapolis. According to The House of the Signing Winds, he delivered that lecture to the Portfolio Club in 1890. The papers collected at the Indiana Historical Society include copies of sixteen different lectures, many of which he delivered on multiple occasions to various groups around the state.

[7] “The State Fair,” Indianapolis Journal, October 2, 1874, 3, Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Art Etchings,” Indiana State Sentinel, April 12, 1876, 2, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Henry Lieber to T. C. Steele, May 24, 1883, reprinted in The House of the Singing Wind, 26; T. C. Steele to James Whitcomb Riley, December 15, 1883, Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library Riley Collection, M0660, Box 2, Folder 6, accessed Indiana Historical Society Digital Collection; "Indiana Artists," Indianapolis Sentinel, April 1, 1885, 4, accessed Chronicling America, Library of Congress; "Mr. Steele's Art Collection," Indianapolis Journal, October 26, 1889, 5, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Commencement Notes," Indianapolis Journal, June 13, 1890, 5, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Art of a High Order," Indianapolis Sun, April 14, 1891, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "An Indiana Man Honored," Goshen Daily News, April 8, 1893, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Annual Exhibitions” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 51, accessed Indiana State Library; Steele, et al, House of the Singing Winds, 11-14, 26-28.

Steele was exhibiting work by 1874 when the Indianapolis Journal reported that he won a gold medal for portraiture at the Indiana Exposition during the State Fair. However, it’s likely that he began exhibiting even earlier. Steele’s journal shows that he had completed about forty portraits by the early 1870s, and therefore, it is possible he would have had works on display – likely at Henry Lieber’s art supply and framing store, H. Lieber & Company Art Emporium, at Washington and Pennsylvania. He was definitely exhibiting at Lieber’s by 1876 when the Indiana State Sentinel printed a small (and not very favorable) review of his work. For a thorough discussion of Steele’s exhibition record during the 1870s see The House of the Singing Winds, 11-14.

While Steele studied in Munich, he sent paintings back to repay his sponsors (Indianapolis businessmen supporting his studies at the Royal Academy). These paintings were received and displayed by Lieber who gave the Indianapolis public a chance to see his improved work in both 1883 and 1884. On May 24, 1883, Lieber wrote to Steele to tell the artist that he had received a group of his paintings and would show them first to those “subscribers” who were funding Steele’s education, and then to the general public. On April 1, 1885, just before Steele returned to Indianapolis from Munich, the Indianapolis Sentinel reported on an exhibition of work by Indiana artists studying in Munich. The paper highlighted Steele’s The Boatman and referred to it as "of more than ordinary merit." While organized by the Bohe Club, this exhibition was also the Second Annual Exhibition of the Art Association of Indianapolis. Steele continued to exhibit work at the annual exhibitions of the Association throughout his life.

In addition to formal exhibitions, Steele exhibited at his studio. (See footnote 5 for more information.) Also, Steele helped students exhibit work. In 1890, his Indiana School of Art held its first annual exhibition. In 1891, the Propylaeum hosted an exhibit where Steele’s work filled “a deservedly prominent place on the walls,” according to the Indianapolis Sun. In 1893, the art jury of the Chicago World’s Fair accepted and exhibited two Steele paintings. The Goshen Daily News reported that one of these works, On the Muscatatuck, received the number one ranking out of 900 paintings.

For information on the exhibition Five Hoosier Painters, which helped bring Steele to national prominence, see footnote 8. For information on exhibitions with the Society of Western Artists, see footnote 9. For information on the 1910 and 1926 retrospectives, see footnotes 18 and 19. Brief summaries of all the exhibitions hosted by the Art Association of Indianapolis and later the Indianapolis Museum of Art (including the Annual Art Association Exhibition and the Annual Exhibitions of the Society of Western Artists) can be accessed via the IMA’s “Past Exhibitions” page of their website: http://www.imamuseum.org/exhibitions/past-exhibitions. Over 65 examples of his work can also be accessed digitally through the IMA “Collections” page: http://www.imamuseum.org/collections.

[8] T. C. Steele to James Whitcomb Riley, December 15, 1883, Indianapolis-Marion County Public Library Riley Collection, M0660, Box 2, Folder 6, accessed Indiana Historical Society Digital Collection; "The Artist Steele: A Visit to His Studio," Indianapolis News, February 19, 1887, 3; "A Painter and a Poet," The (Indianapolis) Sun, October 24, 1891, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Good Pictures This Year," Indianapolis Journal, April 12, 1893, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "City Life," The (Indianapolis) Sun, December 31, 1894, 2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Steele, et al, House of the Singing Winds, 40, 185-86; William H. Gerdts, “The Hoosier Group Artists: Their Art in Their Time,” in The Hoosier Group: Five American Painters (Indianapolis: Eckert Publications, 1985) 20, 26, 28, 31.

Steele and others at the forefront of the Indiana art community noted that Hoosiers had very little appreciation or understanding of fine art. The art community generally attributed the public’s apathy simply to a lack of exposure to fine art. Indeed, most Indiana artists who found success, left for larger cities. See the William Merritt Chase historical marker text for an example. See The Hoosier Group: Five American Painters for more information on Indiana’s art climate in relation to Steele and the other leading Indiana painters of the period.

In 1883, the same year the Art Association of Indianapolis organized to advance art, Steele wrote to James Whitcomb Riley from Munich. Steele was hoping that some of his exhibited work was well received and that “Indianapolis ha[s] made quite an improvement so far as the art feeling is concerned." In 1887, the Indianapolis News reported, "In a general conversation on the subject of art, Mr. Steele remarked that one great difficulty in our city, as in most western towns where art is a new thing, is to get people to look at it seriously and reverently.” To address this lack of interest, Steele delivered scores of lectures on art appreciation (in addition to exhibiting and teaching). See footnote 6 for more information.

By 1893, Steele was rising to national prominence. Indianapolis-based art critic Louis H. Gibson wrote that there were no paintings in any major U.S. city superior to Steele's work. He continued:

To one who is acquainted with the history of art in Indiana, the exhibition by the Art Association at the Propylaeum may well be looked upon with surprise and gratification. In a relatively new part of the country, one in which the minds of the people are largely given to general business, it is not expected that great encouragement will be given to painting or to art generally. This is true of our own city, as it is true of all other Western cities, and to an extent of all cities in this country. Nevertheless, we have had a great and pronounced artistic development. We have artists in our city and State who will do credit to any community.

Gibson wrote his review in response to the Art Association-sponsored Exhibit of Summer, a show which brought the work of Steele and other Hoosiers to the attention of art critic and novelist Hamlin Garland. Garland arranged a second showing of the exhibition at his brother-in-law Lorado Taft's Chicago studio in December 1894. Taft was a famous sculptor and a leader of the Central Art Association which promoted art from the Midwest. The exhibition, renamed Five Hoosier Painters, was a huge success, cementing the reputation of what became known as the Hoosier Group: T. C. Steele, William Forsyth, Richard Gruelle, Otto Stark, and J. Ottis Adams.

Steele and the other Hoosier group artists provided many Indiana residents with their first exposure to nationally recognized fine art. According to professor and historian William H. Gerdts, while Steele was “the most innovative and perhaps forward-looking,” the group shared the conviction that their art should represent the beauty of their home state, thus contributing to a national movement to create a truly American art identity – as opposed to one derivative of European tradition. The art of the Hoosier Group “was distinctively of the heartland.” In 1891, the Indianapolis Sun responded to Steele’s ability to capture the essence of the landscape: "Indiana had picturesqueness enough for him and he has done more than any other artist to perpetuate in the mind's eye her people and scenery.” Again, according to Gerdts, “Steele led the way among the Hoosiers to a cosmopolitan style, to a nativist form of Impressionism, and, incidentally, to national renown for the Indiana school…”

[9] "Pretty: Pictures by Western Artists on Display at the Propylaeum," Indianapolis Sun, March 6, 1897, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Frank Duveneck, Wm. Forsyth, C. F. Browne and F. P. Paulus, “The Society of Western Artists,” Brush and Pencil 1:6 (March 1898): 200, accessed JSTOR; “Art Notes,” Brush and Pencil 2:3 (June 1898): 135-138, accessed JSTOR; "Western Artists," Steubenville Herald-Star, October 20, 1898, 6, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; John H. Vanderpoel, “The Society of Western Artists,” Brush and Pencil 3:3 (December 1898): 152-164; accessed JSTOR; "Review of the Year: Annual Meeting of Indianapolis Art Association," Indianapolis Sentinel, April 4, 1900, 5, submitted by applicant; "An Art Exhibit,' Indianapolis Sun, March 26, 1901, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Sixth Annual Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists,” Brush and Pencil 10:1 (April 1902): 16-26, accessed JSTOR; “Annual Exhibitions” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 54-55, accessed Indiana State Library; “Society of Western Artists: Annual Exhibition,” Art and Progress 6:4 (February 1915): 133-35, accessed JSTOR; Rachel Berenson Perry, T. C. Steele & The Society of Western Artists, 1896-1914 (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 1-3, 12.

Eighteen Midwestern artists, three each from Indianapolis, Cleveland, Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, and Cincinnati, gathered in Chicago on March 11, 1896. The group formed the Society of Western Artists with the aim of increasing public appreciation for Midwestern art. (At the time, the Midwest was often referred to as the West, while those states even further to the west were referred to as the Far West). The Society announced its reason for organizing in the art magazine Brush and Pencil:

…the artists of the Western States … were at a disadvantage as compared to those of the more closely connected communities in the East…It was thought that by a unified action and the organization of a society very much good could be effected, and the work of Western artists brought before the public in a more satisfactory manner than has hitherto been done.

The group held annual exhibitions and was active 1896-1914. The Society organized their annual exhibitions on a six month circuit, with members’ works and juried non-members’ works travelling to the aforementioned cities. The first of these opened December 15, 1896 at the Art Institute of Chicago. This debut exhibition came to Indianapolis and was hung at the Propylaeum in March, 1897. According to art historian Rachel Berenson Perry, “For the next eighteen years, annual shows enjoyed priority scheduling at sponsoring museums and attracted wide-ranging reviews in the nation’s art periodicals.”

The founding Indianapolis artist-members were T. C. Steele, William Forsyth, and J. Ottis Adams. In many ways, the Indiana painters led the movement to reside and paint in the Midwest, as opposed to moving east or overseas as had been the norm for serious artists. According to Perry, because the Hoosier Group was already established and had received national critical acclaim, they “were considered leaders in a potential movement to establish a distinctly American school of painting.” Steele was particularly looked to as a leader both by art critics and Society members. In an 1898 article for Brush and Pencil, writer John H. Vanderpoel wrote:

[The Society] must disclose in its art a vital quality akin to the force which has given character to the people of the West. It must breathe of our great prairies, with its lofty dome of wind-swept clouds; of its blue lakes and placid rivers; its hillsides and valleys in all their moods of color and form…That this feeling finds appreciative response among the members of the society, I need but to refer to such men as T. C. Steele of Indianapolis, who has fathered the ‘Hoosier School of Painters.’ There is a virility in his work that is of the soil.

Also in 1898, the Society elected Steele president for the upcoming season, and Brush and Pencil noted that Steele’s work was purchased by a major Midwest museum. The magazine wrote, “This is a step in the right direction, is practical, and good pictures by Western men find a permanent home, where they may be enjoyed and studied, and an annual record made of artistic growth and change.”

When in Indianapolis, the annual exhibition of the Society of Western Artists was hosted by the Art Association of Indianapolis which considered it to also be the Association’s annual exhibition. In other words, the first annual exhibition of the Society of Western Artists in 1897 was also the Fourteenth Annual Exhibition of the Art Association of Indianapolis. These early exhibitions were held first at the Propylaeum and then Lieber’s Gallery. However, by 1902, the Sixth Annual Exhibition of the Society of Western Artists was held at the John Herron Art Institute.

The Society held its last annual exhibition in 1914, and by 1915, the Society recognized that it had served its purpose. It had provided exposure for its artist-members. Other local museums and art organizations were thriving. Many of the members had moved on in their professional careers. Steele had moved on as well, painting at his Brown County home and teaching at Indiana University in Bloomington. Thus, by 1916, the organization ceased to exist. According to Perry, while the Society of Western Artists did not succeed at creating a “Middle Western buying public,” they did achieve “critical success” and the creation of a Midwestern artistic identity. Commenting on the final exhibition, a writer for Art and Progress concluded:

It must be conceded that this Society has done valuable pioneer work in the West, and deserves full credit for what it has accomplished; it has . . . furnished incentive and opportunity formerly denied to many . . . The establishment of museums in the smaller cities, with local and travelling exhibitions, have reduced the importance or even necessity of these annual exhibitions; they no longer furnish the only means that many formerly enjoyed of seeing what is being produced by Western artists… it must be conceded that it has been of invaluable service and has done a work in the field that could have been done in no other way.

[10]"Art Association's Election," Indianapolis Sun, April 14, 1897, 6, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "New Officers," Indianapolis Sun, April 13, 1898, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "Review of the Year: Annual Meeting of Indianapolis Art Association," Indianapolis Sentinel, April 4, 1900, 5, submitted by applicant; "Art Association Officers," Indianapolis Sun, April 11, 1900, 3, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Pamphlet, Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record, November 29, 1906, 3-4, 49, Indiana State Library; Rachel Berenson Perry, Paint and Canvas: A Life of T. C. Steele (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society Press, 2011), 99.

Since its organization in 1883, the Art Association of Indianapolis maintained three vice-presidents. Steele began serving in the position of one of those vice presidents in 1896 and by the dedication of the new building of the John Herron Art Institute in 1906, he was serving as First Vice-President. That same year he became Chairman of the Fine Arts Committee. He also served on various other committees as well. According to historian Rachel Perry Berenson, Steele served as vice-president of the Indianapolis Art Association until 1908. Even after resigning, he maintained his role as chairman of the fine arts committee and continued judging annual exhibitions.

[11] “Original Articles of Association of the Art Association of Indianapolis,” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 5, 42, accessed Indiana State Library; "Review of the Year: Annual Meeting of Indianapolis Art Association," Indianapolis Sentinel, April 4, 1900, 5, submitted by applicant.

The Art Association of Indianapolis was organized informally April 5, 1883, after an art lecture hosted by educator and women’s rights activist May Wright Sewall. The Association organized formally May 7, 1883 and incorporated October 11, 1883. The importance of the Association in the development of art appreciation in Indiana cannot be overstated. It led the way in hosting important exhibitions and developing art education. See footnotes 14 and 17 for more information.

[12] "Talbott Place for Art Site," Indianapolis Press, January 13, 1900, 2, submitted by applicant; "A Site Selected," Indianapolis Sun, January 13, 1900, 8, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Review of the Year,” Indianapolis Sentinel, April 4, 1900, 5, submitted by applicant; “Art Site Transfer Made,” Indianapolis Sentinel, April 10, 1901, 8, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; May Wright Sewall, “The Art Association of Indianapolis: A Retrospect,” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 15-16, accessed Indiana State Library;

The Association considered several locations before settling on the Talbott property in January of 1900, when, according to the Indianapolis Sun, the Association authorized its finance committee to make the purchase from the current owner, Mary Howe. The Sun reported, "One condition of the purchase will be the closing of a small street north of Sixteenth, and an agreeable price for the property north to Eighteenth-st." There was still some debate about the site until December 1900, when the owners of the neighboring property donated two adjoining lots. With the addition of the adjacent property and closing of a small street or alley separating the properties, the location was made appropriate for the school and museum. According to the Indianapolis Sentinel, the deeds that transferred the two adjoining sites were filed in the recorder’s office April 9, 1901. The deed for the “old Talbott homestead” owned by James T. and Mary C. T. Howe was executed March 22, 1901. The adjoining property (lot 112) known as “Elizabeth Talbott’s subdivision,” according to the Sentinel, was owned by John H. and Adelaide P. Carson. The alley between was “vacated by the board of works,” to the Association by the date of the filing as well.

[13] Newspaper articles in this footnote accessed via NewspaperArchive.com unless otherwise noted: "Art Association Profits," Lowell Daily Sun, May 18, 1895, 4; "Gave Away Thousands," Logansport Reporter, May 18, 1895, 4; "Magnificent Gift," Portsmouth (Ohio) Daily Times, May 18, 1895, 3; "Bequest from an Unknown Patron," The New York World, May 18, 1895, 1; "Attack on John Herron's Will," Logansport Daily Pharos, September 27, 1895, 1; "Wants the Will Set Aside," The (Newark, OH) Daily Advocate," October 20, 1895, 1; "The Will Likely to Stand," Logansport Daily Reporter, December 4, 1896, 4; "The Will Stands," The (Delphos, Ohio) Daily Herald, December 5, 1896, 1; "Artists' Suggestions," Indianapolis Journal, May 27, 1899, 8, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record, November 29, 1906, 3, 13-14, 16, 31-33, 49, Indiana State Library.

The Association named the new institution after its benefactor, John Herron, an Indianapolis resident who made his fortune in real estate. Herron died in 1895, leaving the bulk of his fortune to the Art Association of Indianapolis. His bequest was completely unexpected. Herron was not a member of the Association, nor did any of the Association members reportedly know him personally (although he did attend at least one exhibit). Newspapers from around the country reported on the generous gift and its extraordinary circumstances. The New York World reported, “Herron was unknown to a single member of the association."

The Art Association explained the effect of the gift:

The bequest of John Herron came as a surprise to the Art Association at a time when its affairs looked blackest and when the struggle to continue the work begun more than ten years before seemed almost useless to those who had labored to impress upon the community a realization of the beauty and value of art. . . We must accord to John Herron a high position among men; he has contributed in a wise and far-seeing manner to the education of our youth, to the uplifting of our people, to the greatness of our city.

After several years of Herron’s relatives contesting his will, the Association was able to establish a committee on “investment and expenditure” to determine how to use the over $200,000 bequest. After selecting the location (see footnote 12), the John Herron Art Institute opened in 1902. See footnote 15 on the dedication and opening. For more information on John Herron see: “An Appreciation of John Herron” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record, November 29, 1906, 29-34, Indiana State Library. For more on the will and accompanying litigation, see: Harriet G. Warkel, Martin F. Krause, and S. L. Berry, The Herron Chronicle (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003), 13.

[14] May Wright Sewall, “The Art Association of Indianapolis: A Retrospect,” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 5-10, 37, accessed Indiana State Library; Carl H. Lieber, “The Art School in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 35-41, accessed Indiana State Library; "Educational," Indianapolis Journal, October 14, 1889, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Indianapolis Letter: Written for the Enterprise, Indianapolis, October 28," Farmland Enterprise, November 1, 1889, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; "The Indiana School of Art," Indianapolis Journal, May 3, 1891, 16, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Indiana School of Art," Indianapolis Journal, May 13, 1891, 5, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Art Association at Home,” Indianapolis Sentinel, December 15, 1901, Section 2, 8, accessed Indiana State Library microfilm.

Since its organization in 1883 (see footnote 11), the Art Association of Indianapolis had been working towards creating a center for art exhibition and education in order to increase Hoosiers’ art appreciation. Their first exhibition of 400 loaned paintings ran for three weeks during November, 1883. At this point, Sewall explained of the Association: “They had decided already that it was their duty to provide opportunities for the public to look at pictures; hence the exhibit. They now saw it to be their duty to provide opportunity for instruction in art; hence an art school was conceived.” The Association opened its first art school, the Indiana School of Art, in 1884, but closed it two years later due to lack of funding. The Association’s school was not related to Indiana School of Art directed by James Gookins and John Love during the 1870s or Steele’s school which opened 1889).

In 1885, the Association hosted its second exhibition, Ye Hoosier Colony in Munchen, which included work by Steele and other Indiana painters studying in Munich. Sewall explained that this exhibition “stirred the local pride of Indianapolis and aroused in it a recognition of the possibilities of its own people in art.” She continued, “From 1885 the art exhibit became an important event” and it was held annually. The Association also began building its own art collection, which it housed at the Columbia Club from 1890 to 1896, and afterwards at the Propylaeum, until the John Herron Institute was opened in 1902. A complete listing of the exhibitions to 1906 is found in the booklet, Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record, 51-55.

In 1891, nine Indianapolis businessmen, mainly members of the Art Association, took custody of the Indiana School of Art begun by Steele in 1889. (Again, Steele’s Indiana School of Art was not related to or affiliated with the 1884 Indiana School of Art at its founding. See footnote 6 for more information on the founding of this school.) These men raised money through subscriptions for three years of operation. Most of the subscribers were also members of the Art Association. (For a complete list of subscribers see Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record, 37). This restructuring of the business affairs of the school allowed it to continue until 1897. At this point the school had to give up its building on the Circle to make way for the expansion of the English Hotel (See footnote 6 for more information on the location). According to influential Association member Carl Lieber, “It was not thought necessary to re-establish the school, owing to the prospect of an early realization of the desire for a permanent institution under the will of John Herron.”

Thus, in 1902 with opening of the galleries and classrooms of the John Herron Art Institute, the Art Association finally had a unified physical space for the educational and exhibition-related work they had been undertaking for almost twenty years. See footnote 12 for more information on the opening and description of museum and school space.

[15] "Art Association at Home," Indianapolis Sentinel, December 15, 1901, Section 2, 8, accessed ISL, microfilm; "Herron Art Institute to Be Formally Opened Next Tuesday Evening," Indianapolis Daily Sentinel, March 1, 1902, 7, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Opening of Art Institute," Indianapolis Journal, March 2, 1902, Part Two, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Social and Artistic Is The Opening of the John Herron Art Institute," Indianapolis Sentinel, March 5, 1902, 7, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Herron Art Institute," Indianapolis Journal, March 5, 1902, 10, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; R. L. Polk & Co.’s Indianapolis City Directory for 1904 (Indianapolis: R. L. Polk & Co., 1904), 555, U. S. City Directories, 1821-1989, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; May Wright Sewall, “The Art Association of Indianapolis: A Retrospect,” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 16, accessed Indiana State Library.

In January 1902, the school at the John Herron Art Institute opened with ten students and five teachers, according to the Indianapolis Journal. On February 11, 1902, the Art Association moved from its headquarters at the Propylaeum to the new location. On March 4, 1902, the John Herron Art Institute formally opened with a reception showcasing its galleries. By this point the building had been extensively remodeled, lit with electric lights, and filled with the collection of the Art Association. The following day, the Institute opened to the general public and the Indianapolis Journal reported: “The John Herron Art Institute was thrown open to the public last night…The Art Association had long worked for a home of its own and its hopes were realized in the recent purchase of the Talbott property on North Pennsylvania and the establishment of its art school there.” The newspaper went on to describe the decorating, remodeling, trappings, and paintings. The Journal continued, “For the first time the pictures owned by the association have a home of their own.” The collection included Steele’s “The Oaks at Vernon.”

[16] "Opening of Art Institute," Indianapolis Journal, March 2, 1902, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; "Herron Art Institute," Indianapolis Journal, April 9, 1903, 7, Hoosier State Chronicles; "Plans Accepted for Herron Art Institute," Indianapolis News, July 1, 1903, 1, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Classes at the Herron Art Institute Have Accomplished Much Good Work," Indianapolis Journal, May 15, 1904, 10, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Contract Is Let for Art Institute Building," Indianapolis News, September 20, 1905, 16, accessed ISL microfilm; "Herron Institute Corner Laid," Indianapolis News, November 25, 1905, 1, 2, accessed ISL microfilm; "Mayor Holtzman on Building's Significance," Indianapolis News, November 25, 1905, 1, 2, accessed ISL microfilm; "Work of Now the Important Thing Says T. C. Steele," Indianapolis News, November 25, 1905, 2, submitted by applicant.

As noted above, the school of the John Herron Art Institute opened January 13, 1902 with ten students and five teachers. Numbers increased until there were sixty-nine students by March and the "present quarters [were] crowded." The Indianapolis Journal reported, "Plans are already being made for enlarging the capacity in order to accommodate more pupils.” At the annual meeting of the Art Association at the John Herron Institute in April 1902, the secretary announced that they had acquired several new works of art, that the school had grown to 132 students, and that the association had recently "engaged Vonnegut and Bohn as architects for the new building, who are now working on plans.” In July 1903, the Indianapolis News reported that the Art Association accepted the plans for the new Herron Art Institute designed by Vonnegut and Bohn. The entire building would cost $250,000 but only two-fifths of the building was being erected at this time. The front of the building, facing Sixteenth St., would be built with a temporary wall at the back (north side). "The present building, formerly the Talbot homestead, will be remodeled and joined to the new front." In 1904, the Indianapolis Journal reported that the classes were still growing at the John Herron Art Institute. The classes – in life drawing and painting, still-life painting, and design – were located on the second floor. The "little studio outside" was used for Saturday children's classes.

In the fall of 1905, the Tinker (or Talbott) mansion was demolished to make space for a larger building. The cornerstone of the new building was laid in a ceremony in November 1905. T. C. Steele was a featured speaker at the event. (See footnote 17 for Steele’s speech on this occasion and its relationship to the original goals of the Art Association.) Over time, the John Herron Institute grew extensively and the organization remodeled, replaced, and added buildings on its campus. For the complete history of the institution see: Harriet G. Warkel, Martin F. Krause, and S. L. Berry, The Herron Chronicle (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Herron School of Art IUPUI and Indiana Press, 2003).

[17] “Original Articles of Association of the Art Association of Indianapolis,” in Art Association of Indianapolis, Indiana: A Record (Indianapolis: Hollenbeck Press, 1906), 42, accessed Indiana State Library; "Work of Now the Important Thing Says T. C. Steele," Indianapolis News, November 25, 1905, 2, submitted by applicant; "John Herron Art Institute Building Will Be Ready for Dedication About Middle of May," Indianapolis News, December 11, 1905, 4, accessed ISL microfilm; "Herron Art Institute Building As It Appears To-Day," Indianapolis News, November 17, 1906, 4, ISL microfilm; "Dedicatory Program of Herron Institute," Indianapolis News, November 17, 1906, 4, ISL microfilm; "Glorious Art Treasures at Herron-Institute," Indianapolis News, November 21, 1906, 15, ISL microfilm.

The Art Association of Indianapolis had been working since its organization in 1883, to create a space for Indiana residents to learn about art. (See footnote 14 for a further explanation of the Association’s work in this area to 1902). As stated in the 1883 Articles of Incorporation, the main objects of the Art Association were: “to cultivate and advance Art in all its branches; to provide means for instruction in the various branches of Art; to establish for that end a permanent gallery, and also to establish and produce lectures upon subjects relevant to Art.”

The John Herron Art Institute fulfilled these goals through its classroom and exhibition spaces, beginning with its 1902 opening. However, the Art Association kept working to provide better facilities for learning about and viewing art. As Herron grew quickly (see footnote 16), the Association saw that the building could no longer fulfill both the classroom and exhibition needs. The cornerstone for a new building to replace the Tinker (or Talbott) mansion was laid in 1905. Steele spoke at the 1905 ceremony, and a look at his speech shows how the goals for Herron’s next phase at an enlarged and improved facility continued to align with the original 1883 goals of the Association. According to the Indianapolis News, Steele stated:

In a general way it is our intention to make the institute the center of the art interests and activities of the city and State. . . In the first place we shall expect to take care of current exhibitions. . . These exhibitions will be constantly changing and will be not only a source of enjoyment but a school for the people . . . The second direction in which we expect to work is in building up a permanent collection of high character . . . In the third place, we expect to develop and strengthen the art school now started. . . It is the desire of the management to include not only the education of the draftsman, the painter and sculptor, but to enter the field of design and industrial and applied art.

The new building, which replaced the Tinker mansion, opened in 1906. Herron continued to improve and expand its exhibition and classroom facilities and to grow its collection and student body. As the twentieth century progressed and Herron again outgrew its facilities, the school and gallery functions evolved into separate entities. See footnotes 20 and 21 for more information.

[18] Art Association of Indianapolis, Retrospective Exhibition of the Paintings of Theodore C. Steele (1910), Indiana State Library; W. H. Fox, "To Show Entire Range of T. C. Steele's Work," Indianapolis News, January 29, 1910, 13, Indiana State Library, microfilm.

The Indianapolis Art Association held a retrospective exhibition of Steele paintings at the John Herron Art Institute during the month of February, 1910. Over seventy paintings were displayed, including landscapes and nature studies made in Germany and Indiana, and many portraits, including one of former President Benjamin Harrison. W. H. Fox, Director of the John Herron Art Institute, wrote an article for the Indianapolis News about the importance of the exhibition and of Steele as an artist. He wrote:

It must be of interest to every Indianian, and indeed to all Americans of the west and east who feel a pride in the growth of a native school of painting, and who can appreciate Mr. Steele's influence, potent and widespread, yet quietly and modestly exerted, that it is proposed to honor him by assembling his representative life work in the institution which he has done so much to build up.

[19] Art Association of Indianapolis, Catalogue of the Work of Theodore Clement Steele: Memorial Exhibition (1926), Indiana State Library; J. Arthur MacLean to Mrs. Theodore Steele, et al, September 22, 1926, Box 1, Folder 9, Steele Papers; “Sunday the Final Day of T. C. Steele’s Exhibition,” Indianapolis News, December 25, 1920, 13, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; "Theodore C. Steele Dead," New York Times, July 26, 1926, 15, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; Lucille E. Morehouse, "In the World of Art: Steele Memorial Exhibit Opens at Museum Today," Indianapolis Star, December 5, 1926, pt. 3, 33, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Lucille E. Morehouse, "In the World of Art: T. C. Steele’s Life Work Shown at Art Institute," Indianapolis Star, December 12, 1926, pt. 6, p. 4, Indiana State Library, microfilm.

Steele died July 24, 1926. On December 5, 1926, the Art Association of Indianapolis opened a major retrospective of his work at the John Herron Art Institute. Over 125 paintings spanning his entire career were exhibited through December. While the exhibition included portraiture and street scenes, most of the works were landscapes, many painted in Brookville and Brown County. In two articles for the Indianapolis Star, writer Lucille Morehouse referred to Steele by his often used but informal title of “Dean of Indiana Painters” and as an “Indiana-master.” [Note: Herron hosted exhibitions of Steele’s work besides these two exhibits. For example, in December 1920, his Brown County paintings were featured. However the 1910 and 1926 exhibitions are highlighted here because they were the major retrospectives spanning Steele’s career up to each point.]

[20] "Opening of Herron Art Building Set for Sept. 2," Indianapolis News, August 23, 1929, 6, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Opening of Art School Building," Terre Haute Saturday Spectator, August 31, 1929, 15, NewspaperArchive.com; Lucille E. Morehouse, "Art School Building of John Herron Institute Opened," Indianapolis Star, September 4, 1929, 7, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Art School at Indianapolis," Hammond Lake County Times, September 5, 1929, 4, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Art Association of Indianapolis, The New Art School Building, September 1929, pamphlet, Indiana Collection, Indiana State Library; Corbin Patrick, "Lilly Estate Selected As Site for Art Museum," Indianapolis Star, October 21, 1966, 1, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Herron - I.U. Merger Studied," Indianapolis News, February 3, 1967, 29, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Bill to Restrict Lobbying Passed by State Senate," Brazil (Indiana) Daily Times, February 24, 1967, 2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Art School Move Stirs Concern About Site," Indianapolis Star, November 2, 2000, B5, accessed ProQuest; "Critics Choose Top 5 in Arts and Entertainment," Indianapolis Star, December 31, 2000, I2, accessed ProQuest; S. L. Berry, "A Work of Art: New Herron Building Offers More Amenities and A Presence in Campus Life," Indianapolis Star, May 29, 2005, I1, accessed ProQuest; Brendan O’Shaughnessy, “Herron Building to Retain Arts Theme,” Indianapolis Star, September 16, 2005, B6, accessed ProQuest; Harriet G. Warkel, Martin F. Krause, and S. L. Berry, The Herron Chronicle (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003), 127-41.

By the late 1920s the school and museum had grown to the extent that a separate building was erected for the school. The new building opened early September 1929 with space for 250 students. However, by the early 1960s, the Art Association began discussing the need for even more space for both the school and the museum in its annual reports. According to the Herron Chronicle, a three-story addition in 1962, doubled the size of the school, but still did provide all of the facilities needed to meet the institution’s educational and exhibition goals. By 1966, the Association was proceeding with plans to move the museum and create separate boards for the school and museum [See footnote 21]. During this period of separation and museum planning, the school negotiated with Indiana University. In February of 1967, Indiana University officials and the Board of the Art Association reached an agreement to merge Herron and Indiana University. At the same time, the Indiana General Assembly approved a bill to provide an appropriation for the art school’s operations. The Art Association retained ownership of the property, while IU took over administration. The school remained on the property at 16th and Pennsylvania and expanded into the museum building to provide for additional facilities. (See footnote 21 for information of the museum’s separation and move to a new location). In 1969 the downtown Indiana University satellite campus became Indiana University-Purdue University, Indianapolis (IUPUI), and planning soon began to move Herron to campus.

According to the Herron Chronicle, throughout the 1970s, 80s, and 90s Indiana University worked with the General Assembly to make funding available for the move. By May of 2005, the school changed its name to the Herron School of Art and Design and in June of that year dedicated the new twenty-six-million-dollar building. This building’s formal name is Sidney and Lois Ezkenazi Hall and is located at 735 West New York Street on the IUPUI campus. Explore exhibitions and programming at the Herron School of Art and Design website: http://www.herron.iupui.edu/

In September 2003, the City of Indianapolis received the former Herron property at 16th and Pennsylvania in exchange for land it gave IUPUI. In 2005, the city announced a plan to redevelop the property. Herron High School, a charter school not associated with the Herron School of Art and Design, opened for the 2006-7 school year. Learn more about Herron High School: http://www.herronhighschool.org/

[21] Corbin Patrick, "Lilly Estate Selected As Site for Art Museum," Indianapolis Star, October 21, 1966, 1, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Herron Alters Location Plan," Indianapolis News, June 14, 1967, 2, Indiana State Library, microfilm; "$10 Million Arts Center at Oldfields Is Approved," Indianapolis News, October 25, 1967, 1, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; "Industrialist Announces $4 Million Gift Toward Indianapolis Art Center," Kokomo Tribune, October 26, 1967, 3, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; Jean Jensen, “Art Complex Is Goal of Fund Drive,” Indianapolis News, November 16, 1968, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; “40 Masterworks: A Selection of Paintings in the Indianapolis Museum of Art, Honoring the Inaugural Year of the Museum, 1970-71,” Bulletin: Catalogue 57:1 (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1970), accessed Herron Art Library, IUPUI; The Story of the Indianapolis Museum of Art (Indianapolis: Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1998), 86; Harriet G. Warkel, Martin F. Krause, and S. L. Berry, The Herron Chronicle (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2003).

The Art Association began discussing the need for more space for the school and the museum in the early 1960s. (See footnote 20 on developments relating directly to the school.) In 1966, members of the Lilly family donated their forty-two acre family estate at 38th Street and Michigan Road, known as Oldfields, to the Art Association with the condition that it became the site of the new museum. The Indianapolis Star referred to the property as “spacious,” “park-like,” and “superbly landscaped.” Herman C. Krannert, Chairman of the Board of the Art Association called the gift, "the most magnificent gift in the Association's history and one of the most important in the history of American museums." The twenty-two room mansion located on the grounds housed much of the art collection while a new museum building was constructed “on high ground south and east of the Oldfields mansion,” near 38th Street. The Art Association approved plans for a ten million dollar facility in 1967.

In 1968, the Indianapolis Star reported that the new complex at 38th street would be known as the Indianapolis Museum of Art, which remained under the management of the board of the Art Association. The former museum space on 16th Street would now be known as the Herron Gallery, and would be associated only with the school. The Indianapolis Museum of Art opened to the public in 1970. That year the museum held its inaugural exhibition, “40 Masterworks: A Selection of Paintings in the Indianapolis Museum of Art” and an exhibition of outdoor sculpture, “Seven Outside.” Learn more and explore the collections at the IMA website: http://www.imamuseum.org/