Location: 723 West Fourth Street, Marion (Grant County, Indiana) 46952

Installed 2014 Indiana Historical Bureau and Indiana Landmarks

ID#: 27.2014.1

Text

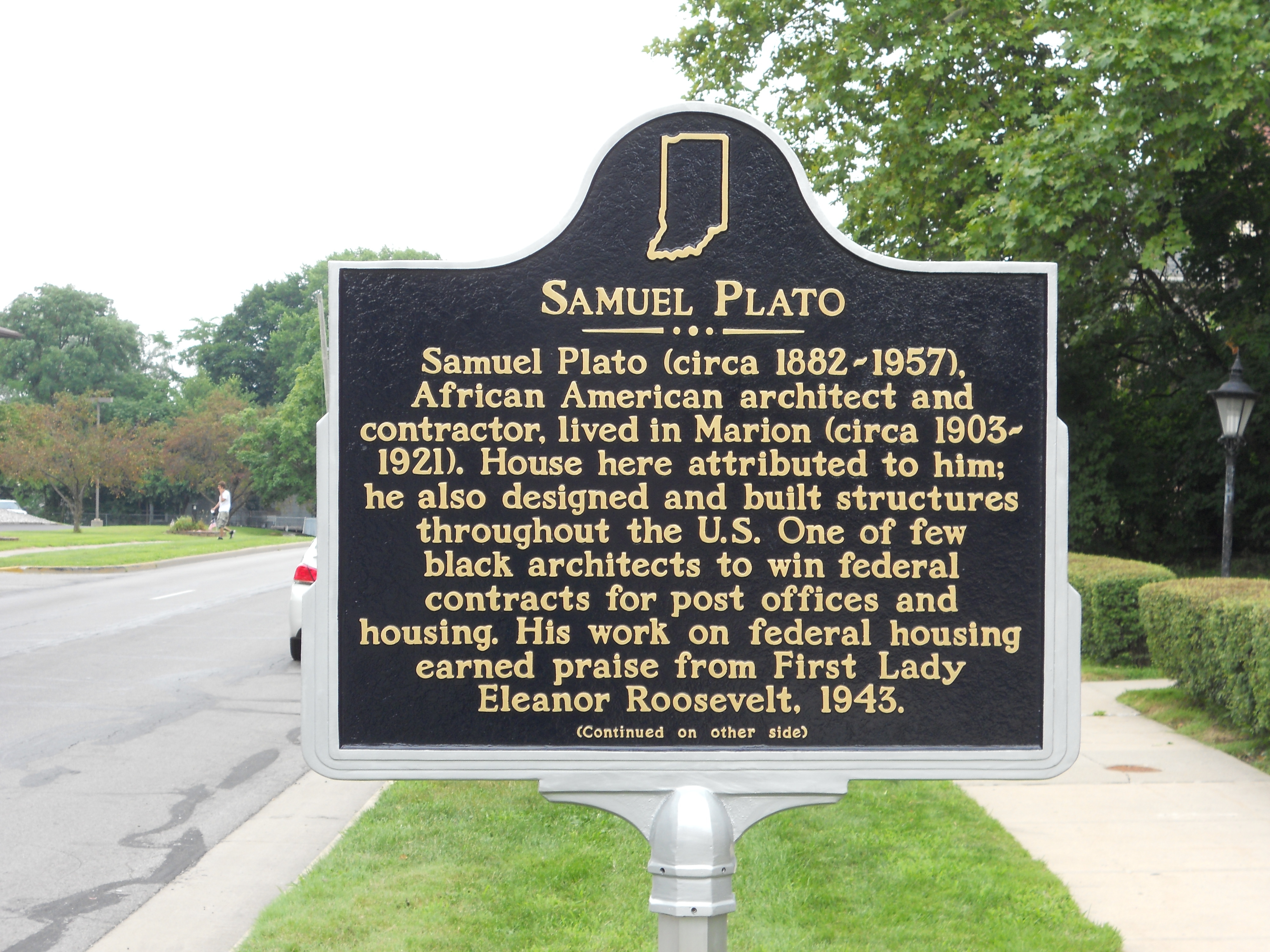

Side One

Samuel Plato (circa 1882-1957), African American architect and contractor, lived in Marion (circa 1903-1921). House here attributed to him; he also designed and built structures throughout the U.S. One of few black architects to win federal contracts for post offices and housing. His work on federal housing earned praise from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, 1943.

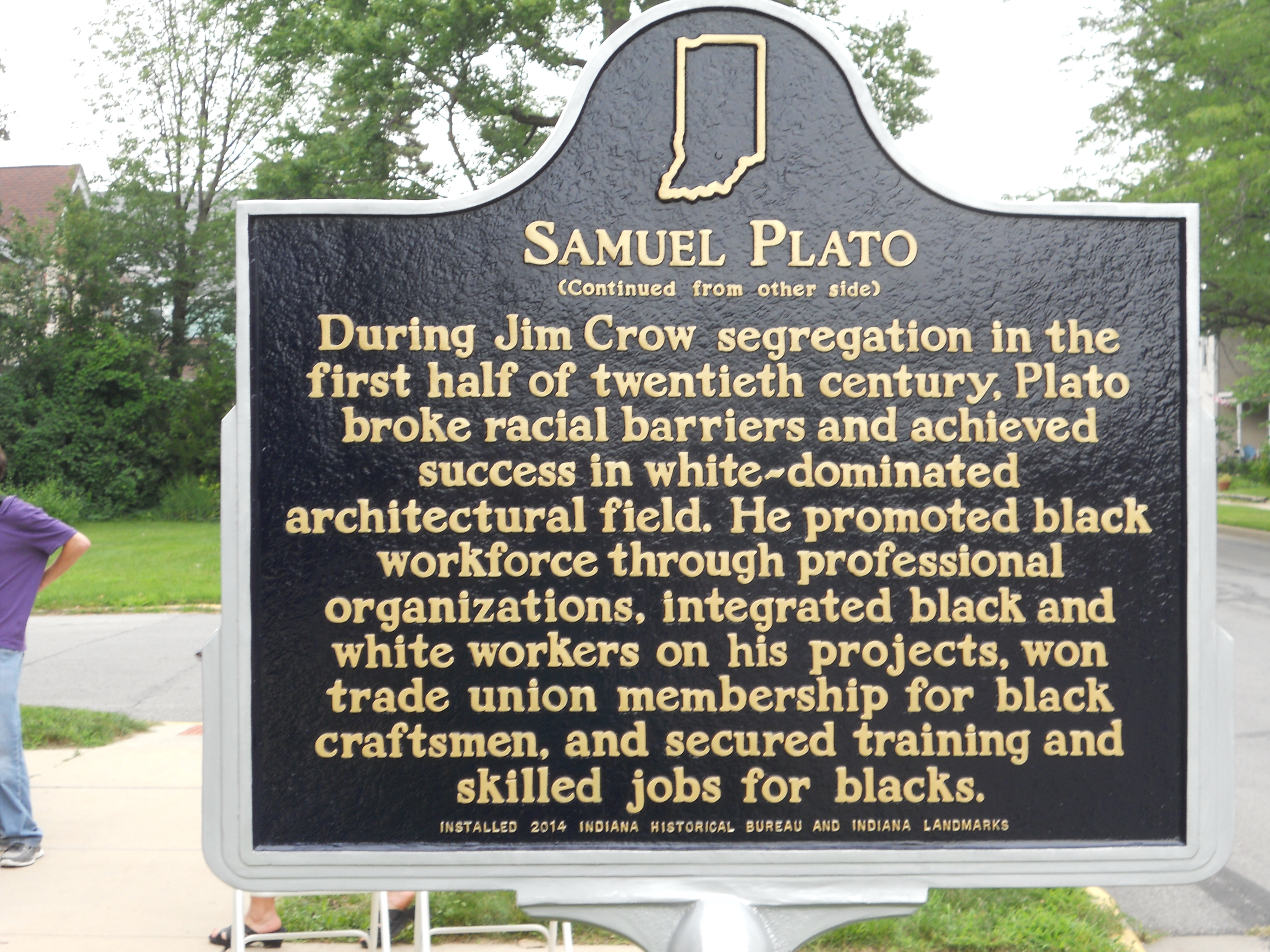

Side Two

During Jim Crow segregation in the first half of twentieth century, Plato broke racial barriers and achieved success in white-dominated architectural field. He promoted black workforce through professional organizations, integrated black and white workers on his projects, won trade union membership for black craftsmen, and secured training and skilled jobs for blacks.

Annotated Text

Side One

Samuel Plato (circa 1882-1957),[1] African American architect and contractor, [2] lived in Marion (circa 1903-1921).[3] House here attributed to him;[4] he also designed and built structures throughout the U.S.[5] One of few black architects to win federal contracts for post offices [6] and housing.[7] His work on federal housing earned praise from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, 1943.[8]

Side Two

During Jim Crow segregation in the first half of twentieth century,[9] Plato broke racial barriers and achieved success in white-dominated architectural field.[10] He promoted black workforce through professional organizations,[11] integrated black and white workers on his projects, [12] won trade union membership for black craftsmen,[13] and secured training and skilled jobs for blacks.[14]

The Samuel Plato Collection and Plato Family Papers, 1924-1967 were accessed through the Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky. All sources accessed at the Indiana State Library are marked “ISL.” The Indianapolis Recorder is accessible through Hoosier State Chronicles.

[1]1900 United States Census (Schedule 1), Precinct 21, Montgomery County, Alabama, Roll 34, page 25B, Lines 88-93, June 27, 1900, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1920 United States Census, Franklin Township, Grant County, Indiana, Roll T625_434, page 10B, Lines 68-9, January 8, 1920, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1930 United States Census, Goshen Township, Tuscarawas County, Ohio, Roll 1885, page 33A, lines 32-3, April 19, 1930, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Fourth Registration Draft Cards (WWII), NARA microfilm publication 1939, Roll 46, Records of the Selective Service System, Record Group Number 147, National Archives, Washington D.C., accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Samuel Plato, “Contracting and Building,” in Report of the Eleventh Annual Convention of the National Negro Business League (Nashville, Tenn.: A.M.E. Sunday School Union, 1911), 69; 1910 United States Census, Franklin Township, Grant County, Indiana, Roll T624_352, page 22B, lines 53-4, April 30, 1910, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Samuel M. Plato (1882-1957),” Louisville Cemetery, Louisville, Jefferson County, Kentucky, accessed Find-A-Grave.com ; World War I Selective Service System Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918, Washington, D.C., National Archives and Records Administration, M1509, Roll 1503894; Kentucky Death Index, 1911-present, Frankfort, Kentucky, Kentucky Department of Information Systems, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Contractor S.M. Plato is Dead at 75,” (Louisville, Kentucky) Courier-Journal, May 15, 1957, Folder 5, Samuel M. Plato: Personal Correspondence and Records, Plato Family Papers, Business Records.

Plato’s exact date of birth is difficult to confirm. Census records mark his birth year anywhere from 1879-1884. The 1900 Census states that Plato was born in 1879, while the 1920 and 1930 Censuses place his birth around 1883. On his WWII draft card, Plato wrote his birthday as January 10, 1884. In a speech Plato delivered to the National Negro Business League (NNBL) in 1910, Plato states that he is 28 years old, placing his birth year at around 1882. The 1910 Census confirms this birth date. This year is also corroborated by Plato’s gravestone in the Louisville Cemetery and his WWI draft card. Plato died in Louisville, Kentucky in 1957.

[2] Plato, “Building and Contracting,” 69-70; R.L. Polk & Co.’s Marion City and Grant County Directory, 1919, p. 406 and 717, accessed ISL microfilm; Marion City Directory, 1921, p. 445, accessed ISL microfilm; Samuel Plato to Mr. John L. Thompson, November 29, 1916, submitted by applicant Marion Public Library; “Green St. Baptist church,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 6, 1948, 15; “Open New Bids for Tyrone Post Office,” Tyrone (Pennsylvania) Daily Herald, January 30, 1930, 1, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “Colored Contractor for A.M.E. Zion Church,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 16, 1915, 1; Marion Indiana Business Directory, 1911-1912, 260, copy in Jon Charles Smith, The Architecture of Samuel M. Plato: The Marion Years, Grant County Projects, 1902-1921, Master’s Thesis, 1998, Historic Preservation, Ball State University, p. 52; Samuel Plato, advertisement, Marion (Indiana) Leader Tribune, February 21, 1914, 4; “Never Build Without Plans,” advertisement, The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), September 13, 1913, 7, accessed Newsbank African American Newspapers, 1827-1998.

According to Plato’s 1910 NNBL speech, he got his start in the building trade when he worked as a carpenter in the summers between his college coursework at Mt. Meigs Institute and the State University of Louisville, Kentucky. He originally pursued a degree in law, but switched to architecture and completed this degree through the International Correspondence Schools of Scranton, Pennsylvania. Throughout his life, Plato appears in newspaper articles, directories, and advertisements as an architect and/or contractor.

[3] Plato, “Contracting and Building,” 70; 1900 United States Census (Schedule 1), Precinct 21, Montgomery County, Alabama, Roll 34, page 25B, Lines 88-93, June 27, 1900, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Marion City Directory and County Gazetteer, 1908-1909, p. 323, in City Directories of the United States, 1902-1935: Marion, IN, accessed ISL microfilm; 1910 United States Census, Franklin Township, Grant County, Indiana, Roll T624_352, page 22B, lines 53-4, April 30, 1910, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; 1920 United States Census, Franklin Township, Grant County, Indiana, Roll T625_434, page 10B, Lines 68-9, January 8, 1920, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; R.L. Polk & Co.’s Marion City and Grant County Directory, 1919, p. 406, 717, inCity Directories of the United States, 1902-1935: Marion, IN, accessed Indiana State Library microfilm;Polk’s Marion Directory and Grant County Gazetteer, 1921, p. 445, 733, inCity Directories of the United States, 1902-1935: Marion, IN, accessed Indiana State Library microfilm; Marion City Directory, 1923, p. 353, 592, accessed ISL microfilm; Caron’s Directoyr [sic] of the City of Louisville, 1922, n.p., accessed AncestryLibrary.com.

Secondary sources that cite Plato as moving to Marion, Indiana in 1902 include Jon Charles Smith, The Architecture of Samuel M. Plato: The Marion Years, Grant County Projects, 1902-1921, Master’s Thesis, 1998, Historic Preservation, Ball State University, 1; “Up a Creek,” Indiana Preservationist, no. 5 (January/February 2005), back cover; Catherine Walden, “A church’s salvation,” Indiana Preservationist, no. 2 (March/April 1998), 14; “Plato, Samuel M.,” in Encyclopedia of Louisville, edited by John E. Kleber (Lexington: University Press of Kentucky, 2001), 708, preview available at googlebooks.com ; “Contractor S.M. Plato,” (Louisville, Kentucky) Courier-Journal, May 15, 1957.

Plato moved to Marion, Indiana circa 1903, and lived and worked in the state until about 1921. Sources do not agree on the exact time period that Plato lived in Marion. Many secondary sources state that Plato lived in Indiana beginning in 1902. However, in his 1910 NNBL speech, Plato claims that he came to the state in 1903 “to begin [his] career as a man of business.” The 1910 Census is the earliest Census record to place Plato in Marion, Indiana, and he was still living there in 1920, according to the Census record for that year. Available Marion City directories for 1908-1909, 1919, and 1921 fill in some of the gaps in the Census records. These directories record Plato as living on either Euclid Ave. or S. Boots St. in Marion throughout his residence in Indiana. Plato left Indiana at some point between 1921 and 1923. The 1922 Marion Directory is unavailable. However, Caron’s Directory of the City of Louisville places Plato at 608 W. Walnut, Louisville, Kentucky in 1922, suggesting that he left Marion some time in 1921 or early 1922. By 1923, Plato is no longer listed in the Marion City directory.

[4] “Thriving City,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 27, 1905; “Samuel M. Plato,” The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), August 9, 1913, 2, accessed Newsbank African American Newspapers, 1827-1998; “Wilson Home,” Samuel Plato Photograph Collection, Filson Historical Society, photocopy; Interior Room, “J. Wood Wilson, Marion, Indiana,” Samuel Plato Photograph Collection, Filson Historical Society, photocopy; Amalia Ray, “Samuel Plato,” The Negro History Bulletin (December 1946), 71; Jon C. Smith, The Architecture of Samuel Plato: The Marion Years, 1902-1921 (Master’s Thesis, Ball State University, 1998), [1]-4, [11], 14,37,56, 68.

“Marion a city of Hustle and Push Inhabitants Wide Awake,” is how the Indianapolis Recorder described Marion, Indiana in 1905. Samuel Plato was listed among the “colored men engaged in business” as a “contractor, who has built some of the finest houses in Marion.” According to a feature story on the African-American community in Marion, published in the Freeman newspaper on August 9, 1913, Samuel Plato earned a contract to build “the palatial residence of the banker, Mr. Wilson, in West Fourth Street” in Marion, Indiana which cost approximately $100,000 to complete. A local newspaper, the Marion Leader-Tribune had reported the “appearance” of the Freeman in the city prior to their feature’s release. Though we have no evidence to show how the Freeman obtained the information for its feature story, it is plausible that the profiled individuals, including Plato, were personally interviewed by Freeman staff.

Labeled photographs of the front exterior of the Wilson House and an interior room were located by the marker applicant in the Samuel Plato Photograph Collection at the Filson Historical Society in Louisville, KY. Additionally, author Amalia Ray published an article on Samuel Plato in the December 1946 Negro History Bulletin wherein she reports that “Plato secured a contract to build the finest residence that has ever been constructed in Marion, Indiana. It was erected at a cost of $135,000.” Ray does not explain how she obtained her information. However, the numerous Plato family stories included in her article suggest an interview with Plato and/or his wife Elnora. No evidence has been located to date to corroborate this assumption.

A search through the Civil Order books of the Grant County Circuit Court (1910-1913) also produced no evidence that Plato worked on Wilson’s mansion. While Wilson and Plato both appear in the court records on separate occasions, they never appear together in the same case. No builder’s liens, mechanic’s liens, or any other land or construction records appear in the Civil Order books for the years when Plato reportedly worked on the house.

Research documenting Plato’s career has not revealed any evidence that Plato did not build the J. Wood Wilson mansion. Evidence collected to date does strongly link Samuel Plato to the Wilson home. Easily accessible primary sources confirming this have not yet been located.

[5] “Samuel M. Plato,” The Freeman (Indianapolis, Indiana), August 9, 1913, 2, accessed Newsbank African American Newspapers, 1827-1998; Samuel Plato, First United Baptist Church, Wabash, Ind.: First Floor Plan, n.d., architectural drawing, in Samuel Plato Collection, submitted by applicant; “Contracts Awarded,” American Contractor, May 26, 1917, vol. 38, no. 21: 62, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Construction Notes,” Paint, Oil and Drug Review, July 4, 1917, vol. 64, no. 1: 26, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Columbia City Short Notes,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) Sentinel, July 9, 1917, 11, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “New Baptist Church for Columbia City,” Fort Wayne (Indiana) Journal Gazette, July 8, 1917, 13, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “Construction Notes,” Paint, Oil and Drug Review, September 19, 1917 vol. 64, no. 12, 26; “Cornerstone Will Be Laid Sunday,” The Indianapolis Star, June 7, 1912, 7, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; The American Contractor, February 16, 1918, vol. 39, no. 7: 41, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Cold Storage and Warehouses,” Construction News, September 25, 1915, vol. 40, no. 13:16, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Samuel M. Plato,” Freeman, August 9, 1913, p. 2, accessed Newsbank African American Newspapers, 1827-1998; Advertisement, Freeman, September 13, 1913, p. 7, accessed Newsbank African American Newspapers, 1827-1998; For other structures Plato built for J.H Schaumleffel, see “Marion, IND.,” The American Contractor vol. 41, no. 6 (February 7, 1920): 63, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Taylor’s Improvements,” Taylor University Echo, vol. 4, no. 1 (October 1916): 20, Taylor Archives, submitted by applicant; Statement to Taylor University from Samuel Plato, November 28, 1916, Marion Public Library, submitted by applicant; “Green St. Baptist church,”Indianapolis Recorder, March 6, 1948, 15; “Post Office Contractor Arrives in Fredonia,”Dunkirk (New York) Evening Observer, May 14, 1935, 9, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Award Contract,” (Massillon, Ohio) Evening Independent, March 26, 1929, accessed NewspaperArchive.com.

Samuel Plato began to build a name for himself as an architect and contractor in Indiana, earning contracts to work on many structures throughout the state. Reporting on Plato’s skill in the architectural field, a 1913 Freeman article commented, “There is no more successful contractor in Grant county, yes, I dare say Indiana, than Mr. Plato.” Primary sources indicate that Plato built or designed the following structures in Indiana: First United Baptist Church in Wabash; Second Baptist Church in Bloomington; a Baptist church in Columbia City; a private residence at 15th and Adams in Marion; Swift & Co. Produce Plant in Marion; a warehouse addition to Atlas Foundry in Marion; the Schaumleffel house in Marion; and Swallow Robin Dormitory, which was added to Taylor University’s campus in Upland, Indiana in 1917. The Wilson-Vaughan (Hostess) House in Marion is also attributed to Plato.

Later in his career, Plato’s success extended to the national level. He designed and constructed buildings across the nation, including the William Stewart Hall at Simmons University (Kentucky), a post office in Fredonia, NY, a Federal building in New Philadelphia, OH, and housing units in Louisville, KY. He was well known throughout the U.S. for his work on federal housing and post office projects. For more on Plato’s work on these structures see footnotes 6 and 7.

[6] “Award P.O. Contract,” Van Wert (Ohio) Times Bulletin, January 18, 1940, 3, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “Weather Expedites Postoffice Building,” Middletown (New York) Times Herald, December 12, 1935, 16, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “Rushing Postoffice Work at Goshen,” Middletown (New York) Times Herald, May 8, 1936, 10, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “Site Clear for New Post Office; Work to Begin Late Next Week,” Hamilton (Ohio) Daily News Journal, August 19, 1936, 7, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “Contract Awarded on Post Office Job,”Charleston (West Virginia) Daily Mail, December 23, 1930, 13, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; “Lettings and Prices,” The Contractor, December 21, 1917, vol. 24, no. 26: 18, accessed googlebooks.com ; United States Public Buildings and Grounds Committee, “Statement of Hon. Edward B. Almon, A Representative in Congress from the State of Alabama,” Hearings Before the Committee on Public Buildings and Grounds, House of Representatives, Sixty-Sixth Congress, First, Second, and Third Sessions (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1921), 3-4, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Master Builder Awarded U.S. Contracts Near $3,000,000,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 7, 1945, sec.1, 27; “Rooster [sic] of Brickmasons: Xenia Armory Job,” June 1930, Folder 1, Samuel M. Plato: Business Records; “Buildings,” Engineering and Contracting, vol. 50, no. 1 (July-December 1918), 34, accessed googlebooks.com ; Harvey C. Smith, “Zanesville Armory,” Ohio General Statistics for Fiscal Year Commencing July 1, 1918, and Ending June 30, 1919, Volume V (Springfield, OH: The Kelly-Springfield Printing Company, 1920), 401, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Approval of Contract Between Samuel Plato and Acting Director of State Armories,” Opinions of the Attorney-General of Ohio for the Period from January 1, 1918 to January 13, 1919, Volume I (Springfield, OH: The Springfield Publishing Company, 1918), 864, accessed googlebooks.com .

Newspaper articles confirm that Plato was awarded contracts to build post offices in Coldwater, Ohio; Goshen, New York; Eaton, New York; Morgantown, West Virginia; and Decatur, Alabama. Plato also won federal contracts for two armories— in Xenia, Ohio and Zanesville, Ohio. The African American newspapers that reported Plato’s federal contracts continually emphasized the significance of his achievement, which suggests that few federal contracts were awarded to African Americans at the time. See footnote 10 for further information on barriers African Americans faced due to racism.

[7] Cornelius L. Bynum, A. Philip Randolph and the Struggle for Civil Rights (Champaign: University of Illinois Press, 2010), 163-176, accessed IUPUI online books; Jessie Parkhurst Guzman, ed., Negro Year Book: A Review of Events Affecting Negro Life, 1941-1946 (Tuskegee, AL: The Department of Records and Research, 1947), 188, accessed internetarchive.org; “Contractor’s Work at Marion Won Praise, Chance for Others,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 1, 1943, sec. 2, 1; “Plato May Get Housing Contract,” The Negro Star (Wichita, Kansas), October 3, 1941, 1, accessed Newsbank African American Newspapers, 1827-1998; “L’Ville Builder Wins Another Gov’t Contract,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 1, 1941, 1; “Gets Million: Project Among Finest; Begins Housing Unit,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 25, 1942, 1; “Samuel Plato, General Contractor Baltimore (Dundalk P.O.) Maryland,” December 22, 1941, in Folder 1, Business Records, Plato Family Papers; “Leading Contractor,” Oakland (California) Tribune, August 2, 1942, 49, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; Federal Works Agency, Public Buildings Administration, “Distribution of Costs,” Langston Stadium Residence Halls, n.d., Folder 1, Business Records, Plato Family Papers; “Applicable Minimum Hourly Rate of Wages,” Langston Stadium Residence Halls, Washington, D.C, n.d., Folder 1, Business Records, Plato Family Papers; Samuel Plato to Brigadier-General Sion D. Hawkins, letter, n.d., Folder 1, Business Records, Plato Family Papers; Federal Works Agency, Public Buildings Administration, “Statement of Vouchers Submitted for Reimbursement,” Langston Stadium Residence Halls, n.d., Folder 1, Business Records, Plato Family Papers; Franklin Delano Roosevelt, Executive Order 8802, June 25, 1941, General Records of the United States Government, National Archives, accessed archives.gov.

Samuel Plato’s work on federal housing for WWII defense workers earned him national recognition as an accomplished African American contractor. He completed contract work on the Wake and Midway Halls dormitories in Washington, D.C., which were added to the Langston Stadium Residence Halls for female African American war workers. He also worked on the Sparrows Point defense housing project in Baltimore, MD.

During WWII, many African Americans and black businesses faced discrimination in national defense industries. Black workers struggled to gain fair employment in war factories, while government organizations overlooked black businesses for war contracts. In protest of this racial discrimination, African American labor organizer A. Philip Randolph proposed a demonstration in Washington, D.C. and formed the March on Washington Movement (MOWM) in 1941. In part as a response to pressure from the MOWM, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt issued executive order 8802 in June 1941, officially banning discrimination in defense jobs and federal defense contract bidding. However, discrimination persisted and the order was often ignored by employers and contractors in defense industries.

According to the Negro Year Book of 1941-1946, Emmer Martin Lancaster, Advisor on Negro Affairs in the United States Department of Commerce, completed a survey of all federal agencies in late 1942 to determine the amount of federal contracts awarded to African Americans. He reported on the continued disadvantage of African American businesses trying to obtain any government war contracts stating, “The lack of information possessed by Negro merchants as to Army and Navy procurement procedure, has reduced to a minimum their business relations with these departments.” Plato was one of the few architects or firms listed in the 1941-6 Negro Year Book’s report on war contracts awarded to African Americans.

[8] Eleanor Roosevelt, “My Day,” May 20, 1943, syndicated newspaper column, in George Washington University’s Eleanor Roosevelt Papers Project; Roger Smith, photographer, First lady inspects war workers’ homes, in Farm Security Administration - Office of War Information Photograph Collection (Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division, 1942-1945), accessed Library of Congress American Memory Project online.

On May 18, 1943, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt embarked on an inspection tour of four federal dormitories erected for African American war workers in Washington, D.C., including Wake and Midway Halls. The two residence halls were built to accommodate more than 800 African American defense workers. Samuel Plato appeared with Roosevelt and Miss W. Gertrude Brown, the resident manager of Wake Hall, in a photograph of the buildings’ dedication. The photograph caption states that Roosevelt “expressed herself as highly pleased with the accommodations.” She later wrote about the inspection tour and Plato’s work on the dormitories in her nationally syndicated newspaper column, “ My Day.”

[9] “Jim Crow” refers to the racist attitudes,policies and laws in the period roughly before the turn of the twentieth century and ending with the accomplishments of the Civil Rights movement. Jim Crow laws were those of segregation and discrimination in housing and employment, and disenfranchisement demanding African Americans use “ separate but equal” facilities from whites. However, the facilities for blacks were, more often than not, inferior to those for whites. Examples of Jim Crow discrimination include requirements that African Americans sit at the back of buses and drink from water fountains marked “Colored.” Samuel Plato experienced such racism on December 19, 1917, when a white restaurant proprietor refused to serve Plato and another African American customer, William L. Evans, because they were black. Plato and Evans sued the restaurant owner for discrimination. See “Negroes Sue Restaurant Men,” Fort Wayne Journal Gazette, December 28, 1917, 6, accessed Newspaperarchive.com. Jim Crow laws also included regulations designed to deny African Americans the right to vote through literary tests. See more examples of Jim Crow laws and signs.

[10] Lillian Serece Williams, Strangers in the Land of Paradise: The Creation of an African American Community, Buffalo, New York, 1900-1940 (Bloomington & Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 1999), 67-79; Michael Adams, “Perspectives: A Legacy of Shadows,” Progressive Architecture (February 1991), accessed galegroup.com; Plato, “Contracting and Building,” 70; Jane Holtz Kay, “Invisible Architects: Minority firms struggle to achieve recognition in a white-dominated profession,” Architecture (April 1991): 106-113; George C. Wright, Life Behind a Veil: Blacks in Louisville, Kentucky, 1865-1930 (Baton Rouge and London: Louisiana State University Press, 1985), 77-101 and 213-228; “Weather Expedites Post Office Building,” Middletown (New York) Times Herald, December 12, 1935, 16, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; Plato & Evans, Odd Fellow’s Hall-Mississinewa Lodge of Marion, Indiana, Samuel Plato Collection; Samuel Plato, First United Baptist Church, Wabash, Ind., Samuel Plato Collection; “Real Estate: Housing boom skyrockets annual sales to over billion for 5,000 colored brokers,” Ebony, vol. 4, no. 1 (Nov. 1948), 15; Monroe N. Work, ed., Negro Year Book: An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro, 1931-1932 (Tuskegee, AL: Negro Year Book Publishing Co., 1931-2), 133, accessed Bloomington Auxiliary Library Facility microfilm; Roosevelt, “My Day,” May 20, 1943.

Samuel Plato entered the job market as a contractor in the early 1900s, a time when employment discrimination limited most African American workers to labor-intensive, unskilled jobs that white workers avoided. In her study of the African American community in Buffalo, NY, Lillian Serece Williams states that employment options open to blacks included jobs as waiters, janitors, gardeners, laundrywomen, and coal shovelers. According to a 1991 article in Progressive Architecture, restrictions on black employment opportunities were largely reinforced by universities created for black students, such as the Hampton Institute and Tuskegee Institute. These black universities were heavily funded by white benefactors who shaped the curriculum to emphasize vocational training for skilled labor at the expense of humanities education such as architecture. Through such curriculum, whites directed the education of black students in ways that limited them to careers of physical labor.

Plato expressed a similar concern in his 1910 speech at the NNBL conference. He explained that he resisted a white neighbor’s encouragement to pursue his talent in carpentry because he “concluded that a white man wanted a black man to do nothing more than hard labor, as lots of it was to be found in the carpenter’s trade.” He chose instead to pursue a career in architecture, which he hoped would open more employment opportunities. As an architect, Plato argued, he “could serve the white man as well as the black man or any other man upon the face of the earth needing shelter…”

Yet throughout his career, Plato was often limited to contracting, building, and carpentry, as demonstrated through the majority of newspaper articles and other sources that identify Plato as the “contractor” or “builder” rather than the architect of various buildings. However, he broke free of this constraint on several occasions when he was hired as an architect to design buildings including the Odd Fellow’s Hall—Mississinewa Lodge (Marion, IN) and the First United Baptist Church (Wabash, IN), for which some architectural drawings can be found in the Samuel Plato Collection at the Filson Historical Society.

African-American architects continue to have difficulty breaking into the architecture profession today. As of 1991, African Americans still only comprised 1.1 percent of the members of the American Institute of Architects. An article that year in Architecture commented, “Find an African-American architect, and you find an architect told that the gentleman’s (i.e., white gentleman’s) profession was not available: you couldn’t join the country club…” Not only did Plato break into the architectural profession, his work was recognized nationally in newspapers, the Negro Year Book, Ebony Magazine, Eleanor Roosevelt’s “My Day” column, and other publications. Plato is also credited with building several structures recognized on the National Register of Historic Places, including the Broadway Temple A.M.E. Church (Louisville, KY) and the Second Baptist Church (Bloomington, IN).

[11] “Contractor S.M. Plato,” (Louisville, Kentucky) Courier-Journal, May 15, 1957; “Builders Meet in Annual Conference,” Broad Axe, February 26, 1927, 2, accessed Newsbank African American Newspapers, 1827-1998; Plato, “Contracting and Building,”69-75; James W. Ivy, ed., The Crisis: A Record of the Darker Races, vol. 59, no. 5 (May 1952): 324, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Special Services in Louisville,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 26, 1949, 7; Samuel Plato to I.B. Higgins, Baltimore Urban League, May 24, 1943, Folder 2, Plato Family Papers, Personal Correspondence and Records; “Special Services in Louisville, Indianapolis Recorder, March 26,1949, 7. Samuel Plato to I.B. Higgins, Baltimore Urban League, letter, 24 May 1943, Folder 2, Plato Family Papers, Personal Correspondence and Records, The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Ky.; Touré F. Reed, Not Alms But Opportunity: The Urban League &The Politics of Racial Uplift, 1910-1950 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008), 12, 28-9;

According to Plato’s obituary in the Louisville Courier-Journal, Plato was active in several professional and community groups including the Y.W.C.A, the Urban League, Phi Beta Sigma fraternity (founded at Howard University, Washington, D.C.—a predominantly black university) and the National Business Men’s League. According to an article in the Broad Axe, Plato was also elected vice president of the National Negro Builders Association in 1927, and he spoke at the group’s annual conference that year. Plato spoke at other business and community meetings, as well. For example, at the 1910 National Negro Business League (NNBL) conference in Washington, D.C., he discussed overcoming racial barriers to achieve success in the architectural and contracting business. Additionally, Plato spoke at Kentucky State College as part of a professional panel on the “vocational opportunities available to college youth,” and at the YMCA headquarters with fellow businessman Joseph Ray. According to Plato’s obituary in the Louisville, Kentucky Courier-Journal, Plato was active in the National Urban League(NUL). While working on the Sparrows Point Defense Housing project (1943), Plato supported the local Baltimore Urban League with a $100 donation. In a letter to the local branch, he stated “It is my opinion that the Urban League through out [sic] the country is doing a substantial job toward the selection of an economic condition, for which unfortunately we are at the bottom of the heap. It is a pleasure to be in a position to render this service.” Created in 1910, the League was dedicated to improving the economic situation of African Americans in major urban areas. NUL addressed social and economic issues facing African Americans in cities such as crime, racial discrimination, unemployment, and sub-standard housing.

[12] “Negroes Do Skilled Work on Building,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 24, 1928, 1; “Contractor’s Work at Marion Won Praise, Chance for Others,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 1, 1943, 1; “Master Builder Awarded U.S. Contracts Near $3,000,000,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 7, 1945, sec. 1, 27; “Leading Contractor,” Oakland (California) Tribune, August 2, 1942, 49, accessed Newspaperarchive.com; Plato, “Contracting and Building,” 73; “Real Estate,” Ebony, 133; Monroe N. Work, ed., Negro Year Book: An Annual Encyclopedia of the Negro, 1931-1932 (Tuskegee, AL: Negro Year Book Publishing Co., 1931-2), 133.

The Indianapolis Recorder and Oakland Tribune mention several times that Plato hired both black and white workers on his construction projects. Plato also states in his 1910 NNLB speech that he was “compelled to use white men for my skilled labor with a few exceptions.” In addition, a 1948 Ebony magazine article on post-war African American housing and real estate indicated that Plato hired white men on one of his government projects. The hiring of white workers by black businessmen was rare at the time. According to the 1931-1932 Negro Year Book, a 1928 national survey of African American Businesses conducted by the National Negro Business League revealed that only 1.2 percent of the employees in black businesses were white. Black contractors and builders across the nation reported just 69 white workers total in their employ. Even this low number was considered an “oddity” by the League.

[13] “Painters’ Union Eases Job Ban,” The (Baltimore, Md.) Afro American, January 31, 1942, p.14; “100 Union Carpenters Get Jobs in Fortnight,” The Afro American, April 28, 1942, p.5; “Union Finally Lets Down Bar,” The Afro American, May 9, 1942, p. 10; “Plato’s Construction Work,” The Afro American, January 9, 1943; “Labor,” The Afro American, April 24, 1943; “Contractor’s Work at Marion Won Praise, Chance for Others,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 1, 1943; “Samuel Plato, Kentucky Contractor with Offices in Washington DC and Louisville,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 7, 1945; Amalia Ray, “Samuel Plato,” The Negro History Bulletin (December 1946), 71; Jon C. Smith, The Architecture of Samuel Plato: The Marion Years, 1902-1921 (Master’s Thesis, Ball State University, 1998), 51.

In her 1946 article, author Amalia Ray refers to Plato’s early activities to obtain building trade union membership for skilled black craftsmen. When Plato received a contract to build the J. Wood Wilson mansion in Marion, Indiana, white carpenters (some of whom had refused to work with Plato earlier) asked to be employed on the project. Plato told them that he would hire them “provided that they admitted all of Plato’s Negro mechanics into the union. . . . after an all night session the Negro mechanics were admitted to the union. This started a crusade throughout the state of Indiana to accomplish the same result wherever Plato got a contract to erect a building.” Unfortunately, author Jon Smith, “after considerable research,” did not locate any sources to corroborate Ray’s statements.

However, in January 1942, The (Baltimore, Md.) Afro American newspaper reported, “The first step toward eliminating discrimination in the AF of L’s all white local Painters’ Union came this week when it granted work permits to two colored painters for employment on the $1,276,000 Sparrows Point housing project at Turners Station.” Plato was the general contractor for this federal government project. He planned to hire more “colored painters. . . as soon as they are able to secure work permits from Local No. 1 of the painters’ union here.”

In January 1943, the Afro American reported, “Samuel Plato, contractor par excellence, came to Baltimore with his construction company and did a job that will always be remembered. . . . White contractors and white business agents of local craft unions had their eyes opened to events which they would have insisted could not happen here. But they did happen and everybody lived to tell the story of colored and white skilled workers taking orders from an unassuming, but highly competent, colored contractor.”

Plato was one of three “colored leaders” recognized by Afro American columnist Edward S. Lewis. “Mr. Plato has been a union contractor for many years and one of the secrets of his success is the extraordinary co-operation which he gets from AFL building craft unions. He also breaks down barriers as he goes along. Witness, for example, the success which his company had for the first time in Washington, in getting colored carpenters accepted on union jobs.”

[14] “Contractor’s Work at Marion Won Praise, Chance for Others,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 1, 1943, 1; Jacob W. Powell, Bird’s Eye View of the General Conference of the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church with Observations on the Progress of the Colored People of Louisville, Kentucky and a History of the Movement Looking Toward the Elevation of Rev. Benjamin W. Swain, D.D. to the Bishopric in 1920 (Boston: The Lavalle Press, 1918), 6, accessed googlebooks.com ; “Ohio Insurance Co., to Dedicate New Building,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 31, 1928, 6; Plato, “Contracting and Building,” 73.

Several newspaper articles mention that Plato offered African American workers the chance to work on his projects. For example, a May 1, 1943 article in the Indianapolis Recorder reports that, “…a large number of Negro carpenters were brought into the local union through Mr. Plato’s efforts” so that they could work on his war housing project for Wake and Midway Halls in Washington, D.C. The same article highlights other African Americans who found an opportunity to practice their professional skills in Plato’s business including James Braxton, the chief engineer, and Milton Wilson, a cost accountant. On another contract to build the African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church in Louisville, Kentucky, Plato hired mostly African American “masons, carpenters and laborers.” At the 1910 NNBL conference, Plato also stated, “I am giving as many of our boys a chance to learn trades as I possibly can, and use my influence whenever and wherever I can to get them into the factories. One firm has in the last year given 25 or 30 of our boys an opportunity to learn the molders’ trade…”

Keywords

Buildings & Architecture, Architect, African American