Location: Hamilton Heights Student Activity Center, 420 West North St., Arcadia (Hamilton County, Indiana) 46030

Installed 2019 Indiana Historical Bureau and Hamilton Heights School Corporation

ID#: 29.2019.1

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog or

Visit the Indiana History Blog or  listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about how Ryan White and Tony Cook, Hamilton Heights principal, used education to overcome AIDS stigma.

listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about how Ryan White and Tony Cook, Hamilton Heights principal, used education to overcome AIDS stigma.

Text

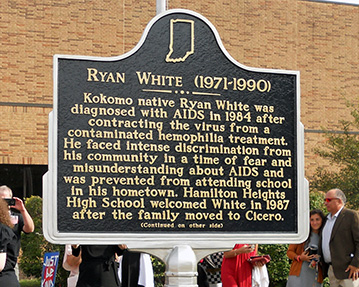

Side One

Kokomo native Ryan White was diagnosed with AIDS in 1984 after contracting the virus from a contaminated hemophilia treatment. He faced intense discrimination from his community in a time of fear and misunderstanding about AIDS and was prevented from attending school in his hometown. Hamilton Heights High School welcomed White in 1987 after the family moved to Cicero.

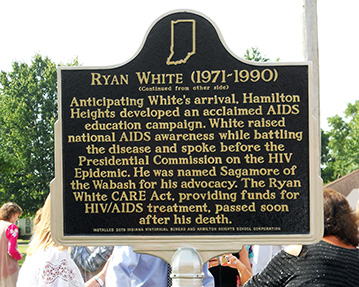

Side Two

Anticipating White’s arrival, Hamilton Heights developed an acclaimed AIDS education campaign. White raised national AIDS awareness while battling the disease and spoke before the Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic. He was named Sagamore of the Wabash for his advocacy. The Ryan White CARE Act, providing funds for HIV/AIDS treatment, passed soon after his death.

Summary

Born on December 6, 1971, Ryan Wayne White was diagnosed with hemophilia A three days after birth. Ryan received Factor VIII injections, which contain clotting agents extracted from blood plasma, to treat the symptoms caused by his illness. In the early years of the AIDS epidemic, there was no laboratory test available to screen blood products for the disease, meaning that many people who received blood transfusions, Factor VIII injections, and other blood-based treatments contracted HIV/AIDS from contaminated products. This was the case for White, who was diagnosed with AIDS in December 1984 at Riley Hospital for Children in Indianapolis.

After his diagnosis, the Western School Corporation superintendent and school board denied Ryan admittance to Western Middle School in Russiaville, Indiana. He cited the schools “habit of keeping kids out who have communicable diseases,” as well as concerns about the safety of other students. In order to ensure Ryan had access to education, the school set up a phone line through which Ryan could listen to lectures and participate in class, although the sound was often garbled and the system ineffective.

In July 1985, the Indiana Board of Health issued guidelines for children with AIDS attending school. The guidelines stated, “AIDS. . . children should be allowed to attend school as long as they behave acceptably. . .and have no uncoverable sores or skin eruptions.” In November, the Indiana Department of Education ruled that Ryan was to be admitted to classes at Western Middle School. After a series of appeals, restraining orders against Ryan, and other legal actions, Ryan’s crusade to attend school, which by this time had garnered national attention, was successful and he returned to school in April 1986.

In school and out, Ryan faced intense discrimination while living in Kokomo. In a 1988 statement, Ryan recalls this time:

Some restaurants threw away my dishes, my school locker was vandalized inside and folders were marked ‘fag’ and other obscenities. I was labeled a troublemaker, my mom an unfit mother, and I was not welcome anywhere. People would get up and leave so they would not have to sit anywhere near me. Even at church, people would not shake my hand.

Because of this hostility, the Whites moved away from the town in which both Ryan and his mother Jeanne were born. The family settled thirty miles away in Cicero, Indiana in May 1987. Hamilton Heights High School principal Tony Cook received word that the Whites were intending to move to his district in April and immediately began laying the groundwork for a smooth transition. With support from his superintendent and school board, Cook made the decision that Ryan would be admitted, without restriction, as long as he was healthy enough to attend school. With that decision made, Cook, Hamilton Heights High School, and the community of Cicero set out to ensure that Ryan was welcomed with open arms into the community.

After speaking with the Indiana Department of Health and collecting all available information on AIDS he could find, Cook made himself available to anyone in the community who had questions or concerns about Ryan living and attending school in the area. Over that summer, Cook addressed rotary clubs, Kiwanis Clubs, churches, and individual community members, all in an effort to assuage fears and educate the public.

During the first two days of classes, in the 1987-1988 school year, Principle Cook addressed the student body, educating them on the situation and answering any and all questions or concerns. He recruited members of the student government to act as student ambassadors to speak with students, support Ryan, and face the press. In the end, only three families decided not to send their children to school when Ryan began attending classes. He spoke about his family’s acceptance into the community, saying:

“We did a lot of hoping and praying that the community would welcome us, and they did. For the first time in three years, we feel we have a home, a supportive school, and lots of friends.”

Learn more about the Hamilton Heights AIDS education campaign on the Indiana History Blog. (link)

Ryan became a nationally known AIDS education advocate because of his experiences. He became the so-called “poster child” for the AIDS crisis and appeared in fundraising and educational campaigns nation wide. He appeared on television, was involved in the production of the biographical movie The Ryan White Story, spoke in schools, and testified in frony of the Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic, all while battling the disease. Through this work, Ryan became close with many celebrities, including Elton John, Michael Jackson, and his celebrity crush Alyssa Milano.

Ryan was admitted to Riley Hospital for Children on March 29, 1990 with a respiratory infection. He died on April 8, 1990. Just months later, congress passed the Ryan White Comprehensive AIDS Resources Emergency (CARE) Act. The act provides federal funding for HIV and AIDS community-based care and treatment services.

Annotated Text

Side One

Ryan White (1971-1990)[1]

Kokomo native Ryan White was diagnosed with AIDS in 1984 after contracting the virus from a contaminated hemophilia treatment.[2] He faced intense discrimination from his community in a time of fear and misunderstanding about AIDS and was prevented from attending school in his hometown.[3] Hamilton Heights High School welcomed White in 1987 after the family moved to Cicero.[4]

Side Two

Ryan White (1971-1990)

Anticipating White’s arrival, Hamilton Heights developed an acclaimed AIDS education campaign.[5] White raised national AIDs awareness while battling the disease and spoke before the Presidential Commission on the HIV Epidemic.[6] He was named Sagamore of the Wabash for his advocacy.[7] The Ryan White CARE Act, providing funds for HIV/AIDS treatment, passed soon after his death.[8]

[1] Attendance record, Ryan White, Hamilton Heights High School, 1987-1990, submitted by applicant; Marion County Health Department Certificate of Death, filed April 10, 1990, submitted by applicant; “Ryan Wayne White,” U.S. Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007, Social Security Administration, accessed AncestryLibrary.com.

[2] “Hoosier Boy Gets AIDS,”[Franklin] Daily Journal, January 8, 1985, 12; “Hemophilia Patient Stricken With AIDS,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, January 9, 1985, 1; “Hemophiliac Boy Sues After Contracting AIDS,” [Lafayette] Journal and Courier, March 12, 1985, 1; “The Happier Days for Ryan White,” The Saturday Evening Post, (March 1988): 52-53; Ryan White and Ann Marie Cunningham, Ryan White: My Own Story, New York: Dial Books, 1991, 36-67; Jeanne White, “Weeding out the Tears,” New York: Avon Books, 1997, 60-70.

[3] “Exhibit A: Guidelines for Children With Aids/ARC Attending School,” Indiana State Board of Health, July 1985, Indiana Archives and Records Administration; “Kokomo Area School Blocks AIDS Victim,” Indianapolis Star, July 31, 1985, 1; “Interested ICLU Sees Ryan’s Case as One of Discrimination,” Indianapolis Star, August 4, 1985, 22; “Parents Threaten Suit to Bar AIDS Victim,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, August 13, 1985, 1; “Court to Rule Friday on Aids Victim’s Suit,” [Muncie] Star Press, August 14, 1985, 2; “AIDS Outcast to Attend Kokomo School by Phone, [Elwood] Call-Leader, August 24, 1985, 4; “AIDS Radio Ads Biased, Kokomo School Chief Says,” Muncie Evening Press, August 30, 1985, 7; “A Boy’s Illness Divides, Wounds His City,” [Lafayette] Journal and Courier, February 22, 1987, 1; Andrew Carroll and Robert Torricelli, In Our Own Words: Extraordinary Speeches of the American Century, Kodansha America: New York, 1999, 377-379.

[4] “County AIDS Group Supports White Family,” Noblesville Ledger, April 30, 1987, 1; “Cicero accepts Ryan White,” [Franklin] Daily Journal, August 28, 1987, 3; “No Protest Marks Ryan’s School Day,” Noblesville Ledger, August 31, 1987, 1; “Arcadia Accepts Young Aids Victim,” [Muncie] Star Press, September 16, 1987, 10; Attendance record, Ryan White, Hamilton Heights High School, 1987-1990, submitted by applicant.

[5] “Ryan White to Start New School Monday,” [Muncie] Star Press, August 30, 1987, 4; “Hamilton Heights Cited as Example for AIDS Education,” [Muncie] Star Press, September 6, 1987, 26; “High Schools Increase Instruction on AIDS Dangers,” Reno Gazette-Journal, September 6, 1987, 6; “Ryan White: ‘Good’ Life in a New Town,” [Twin Falls] Times-News, October 25, 1987, 24; “Ryan White Says He’s Happy, Looks Ahead,” [Jasper] Herald, March 4, 1988, 30; “AIDS Victim Ryan White Called Inspiration to Class,” [Eau Claire] Leader-Telegram, March 5, 1988, 12; “Ryan White’s High School Wins AIDS Education Award,” South Bend Tribune, December 10, 1995, 42; Tony Cook, interview by Lindsey Beckley, June 24, 2019, available upon request at Indiana Historical Bureau.

[6] White spoke before the commission on March 3, 1988. The official name of this commission is the “Presidential Commission on the Human immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic,” although it is almost always referred to as the “AIDs Commission” or the “President’s Commission on AIDs.”

“Executive Order 12601 of June 24, 1987: Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic,” Federal Register, (June 1987) Volume 52, 124, Accessed Presidential Documents, Library of Congress; “Ryan White Will Present Paper Before Presidential Commission,” [Muncie] Star Press, February 28, 1988, 42; “Ryan White Says He’s Happy, Looks Ahead,” [Jasper] Herald, March 4, 1988, 30; Doug McDaniel, “From Outcast to Acceptance,” Indianapolis Star, March 4, 1977, 1; Jerry Estill, “AIDS Victim Ryan White Called Inspiration to Class,” [Eau Claire] Leader-Telegram, March 5, 1988, 12; “AIDS Education,” [Clarksville] Leaf-Chronicles, March 25, 1988, 23; Lee Mitgang, “Ryan White Urges Educators to Teach Truth About AIDs,” [Jasper] Herald, July 5, 1988, 4; “Teen Asks for AIDS Education,” Pensacola News Journal, July 5, 1988, 3; W.C. Madden, “Heights Teens ‘Speaks Out’ on Aids Issue at Museum,” Noblesville Ledger, August 3, 1988, 1; Lynne Heffley, “Television Reviews: Teen’s Story Puts Human Face on AIDS Education,” Los Angeles Times, October 29, 1988, 84; Ryan White and Ann Marie Cunningham, Ryan White: My Own Story, New York: Dial Books, 1991, 290-297.

[7] “Governor Honors Ryan White,” (Greenfield) Daily Reporter, December 19, 1987, 8; “Orr Honors Ryan White, Mom,” (Columbus) Republic, December 19, 1987, 12; “Governor Orr Honors Ryan White,” (Seymor) Tribune, December 19, 1987, 16; Image of Sagamore of the Wabash Award presented to Ryan Wayne White, submitted by supplicant; Email correspondence, James Nossett to Lindsey Beckley, Re: Sagamore of the Wabash Language, April 11, 2019.

Keywords

Science, Medicine, and Invention; Education and Library