Location: 300 N. Capitol Ave., Corydon, between the Harrison County Courthouse and the First State Capitol building (Harrison County, Indiana)

Installed 2016 Indiana Historical Bureau, Harrison County Committee for the Indiana Bicentennial, and Leora Brown School

ID#: 31.2016.1

Text

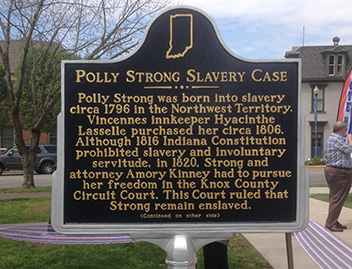

Side One:

Polly Strong was born into slavery circa 1796 in the Northwest Territory. Vincennes innkeeper Hyacinthe Lasselle purchased her circa 1806. Although 1816 Indiana Constitution prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude, in 1820, Strong and attorney Amory Kinney had to pursue her freedom in the Knox County Circuit Court. This Court ruled that Strong remain enslaved.

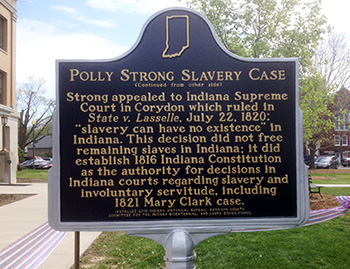

Side Two:

Strong appealed to Indiana Supreme Court in Corydon which ruled in State v. Lasselle, July 22, 1820: “slavery can have no existence” in Indiana. This decision did not free remaining slaves in Indiana; it did establish 1816 Indiana Constitution as the authority for decisions in Indiana courts regarding slavery and involuntary servitude, including 1821 Mary Clark case.

Annotated Text

Side One:

Polly Strong was born into slavery circa 1796 in the Northwest Territory.[1] Vincennes innkeeper Hyacinthe Lasselle purchased her circa 1806.[2] Although 1816 Indiana Constitution prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude,[3] in 1820, Strong and attorney Amory Kinney had to pursue her freedom in the Knox County Circuit Court.[4] This Court ruled that Strong remain enslaved.[5]

Side Two:

Strong appealed to Indiana Supreme Court in Corydon which ruled in State v. Lasselle, July 22, 1820: “slavery can have no existence” in Indiana.[6] This decision did not free remaining slaves in Indiana;[7] it did establish 1816 Indiana Constitution as the authority for decisions in Indiana courts regarding slavery and involuntary servitude, including 1821 Mary Clark case.[8]

A note about primary sources used: The records of the Knox County Circuit Court, 1817-1823, have been used extensively throughout the annotations for this marker text. The actual Knox County Circuit Court court case files for Polly vs. Lasselle can be found at “Bound for Freedom: the Case of Polly Strong” accessed Courts in the Classroom. Those documents used here are individually cited and copies are available in the marker research files at Indiana Historical Bureau. Indiana Supreme Court records for Polly’s case, State vs. Lasselle, are available at the Indiana State Archives. Copies of the records used in these notes are also available at IHB. The Knox County Circuit Court Order Books for 1817-1821 and 1821-1825 are available on microfilm at the Indiana State Library. Indiana newspapers cited herein are available online at “Hoosier State Chronicles” unless otherwise specified.

[1] “Marguerite,” April 11, 1819, Register of Baptisms, Marriages, etc., 1749-1838, St. Francis Xavier Church, Vincennes, typed copy, Knox County Reel 2, Indiana State Library, microfilm; “Opinion of John Johnson Attorney as to Polly, Negress,” circa 1816, Lasselle Family Collection, Manuscripts and Rare Books, Indiana State Library, microfilm 00529; “Petition of Jenny for Habeas Corpus,” July 15, 1818, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; “Return to Summons for Habeas Corpus, Hyacinthe Lasselle,” January 28, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; “Replication, Polly Strong,” January 28, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; “A List of letters remaining in the Post Office,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, October 11, 1823, 2; “A List of letters remaining in the Post Office,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, April 3, 1824, 3; Emma Lou Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana, A Study of a Minority (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1957), 2, 3, 8-11; Paul Finkelman, “Evading the Ordinance,” Journal of the Early Republic 9, no. 1 (Spring 1989): 21-51; Paul Finkelman, “Almost a Free State, The Indiana Constitution of 1816 and the Problem of Slavery,” Indiana Magazine of History 111, no. 1 (March 2015): 64-95, accessed Indiana Magazine of History Online Resources.

Much of what we know about Polly Strong is derived from the records of the Knox County, Indiana Circuit Court cases cited above. Strong’s mother, Jenny, was enslaved and kidnapped by American Indians. After the Treaty of Greenville (1795), Jenny was sold by Indians to trader Antoine Lasselle living near Ft. Wayne. Jenny had two children—Polly born 1796 and James born circa 1800. Antoine sold Polly to Joseph Barron and sold James to “a certain LaPlante.” Hyacinthe Lasselle bought Polly circa 1806 and later bought James.

Polly was baptized in St. Francis Xavier Catholic Church, Vincennes, April 11, 1819. The Register of Baptisms, Marriages Etc., 1749-1838, gives her baptismal name as Marguerite and describes her as a “mulatto belonging to Mr. Lassel, daughter of one named Strong and Jeney. . . .”

Polly Strong was mentioned in the Vincennes Western Sun as late as April 4, 1824, when a letter at the Vincennes Post Office awaited her pickup. No later reference to her has been located for this project.

According to historian Emma Lou Thornbrough, the presence of slaves, both African and Indian, belonging to French traders and Catholic priests, was recorded as early as 1746 in the area that became Indiana. When Great Britain took control of the area in 1763, the legal holding of slaves as property continued.

The Treaty of Paris (1783) ended the American Revolution; it promised to honor the property rights of the new country’s French and British inhabitants. And, though the Continental Congress’s plan for governing the newly acquired territory north and west of the Ohio River—the Northwest Ordinance, 1787—prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude, most territory officials interpreted the anti-slavery Article VI as a prohibition against bringing slaves from other states and territories into the territory while sustaining the property rights of long-time inhabitants.

The interpretation and authority of Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance continued to be argued in Indiana county courts even after statehood in 1816.

[2] For more information about Hyacinthe Lasselle and the Lasselle family, see Lasselle Family Collection Guide, Lasselle Collection, Rare Books and Manuscripts, Indiana State Library.“Theatre,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, January 2, 1819, 3; “Regimental Orders,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, January 16, 1819, 3; “Valuable Property For Sale,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, May 1, 1819, 3; “For Sale At Public Auction,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, November 20, 1819, 3; Warrant for Arrest, Joseph Huffman, January 28, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; “Return to Summons for Habeas Corpus, Hyacinthe Lasselle,” January 28, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Complaint, Lasselle v. Huffman, February Term 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; “Sheriff’s Sale,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, March 29, 1823, 3; “Communicated,” The [Logansport, Ind.] Telegraph, February 4, 1843; Henry S. Cauthorn, A Brief Sketch of the Past, Present and Prospects of Vincennes (Vincennes, Ind.: 1884), 28-29, accessed at Hathi Trust Digital Library; Charles B. Lasselle, “The Old Indian Traders of Indiana,” Indiana Magazine of History 2, no. 1 (March 1906): 1, 6, 12, accessed at Indiana Magazine of History Online Resources; E. F. P. C. S. Fabre-Surveyer, From Montreal to Michigan and Indiana [Lasselle family] (Ottawa: Royal Society of Canada, 1945), [Introduction], 1-8; Francis Philbrick, ed., The Laws of Indiana Territory, 1801-1809 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, reprint 1931), 196-99, accessed at Road to Indiana Statehood; Dorothy Riker, ed., Executive Proceedings of the State of Indiana, 1816-1836 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau, 1947), 194, accessed at Road to Indiana Statehood.

Secondary sources authored by Cauthorn, Lasselle, and Fabre-Surveyer provide biographical information about the Lasselle family. Hyacinthe Lasselle’s father, Jacques, was a Frenchman born in Montreal, Canada; he traded with the native peoples at Detroit and then Kekionga (Ft. Wayne after 1794). Jacques’ four sons, including Hyacinthe, became traders also. Hyacinthe, was born 1777 at Kekionga and began trading with the Indians along the Wabash River circa 1795. Lasselle moved to Vincennes, the capital of Indiana Territory in 1804. He was appointed by the Indiana House of Representatives and Legislative Council in 1806 as one of the first Trustees of the Borough of Vincennes; he purchased Polly Strong in 1806. He fought in the War of 1812. He was a leader in the local militia and, in 1821, Governor Jonathan Jennings gave him a commission as his Aid-de-Camp. Early nineteenth-century Vincennes newspapers demonstrate that Lasselle was a prominent citizen of Vincennes; he engaged in land sales, operated a distillery, and kept a bar and inn. In 1833, Hyacinthe and his family moved to Logansport where he died in 1843.

[3] Habeas Corpus suits listed in Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 32, 37, 62,63, 104, 158-59, 179, 196, 217, 257, 271, 306, 357-60, 396, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Katy, a girl of color vs. Jean Bte. Laplant, Habeas Corpus, July 1818, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 159, Indiana State Library, microfilm; William Henry Smith, ed., The St. Clair Papers vol. II (Cincinnati: Robert Clarke & Co., 1882), 325-26, 330-31; Philbrick, Laws, 136-39, 523-26; Thornbrough, The Negro in Indiana, 2, 3, 8-11; Finkelman, “Evading the Ordinance,” 21-51; James H. Madison, “Race, Law, and the Burdens of Indiana History,” in The History of Indiana Law, David J. Bodenhomer and Hon. Randall T. Shepard, eds., (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2006), 37-59; Finkelman, “Almost a Free State,” 64-95; Indiana County Level Results 1820, Historical Census Browser, University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center, accessed http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/.

Historian Paul Finkelman, in his article “Almost a Free State,” described ways for enslaved persons living in Indiana to obtain freedom: their owners could give them their freedom; the enslaved could hire attorneys to pursue their freedom suits in a county court of law; or they could try to escape.

As early as 1794, an enslaved African American and his wife applied to Northwest Territory Judge George Turner for freedom from owner, Henry Vanderburgh. Judge Turner opined that Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery altogether and the couple should be freed. Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, told the judge that the Ordinance did not affect enslaved persons already in the area before the Ordinance was enacted in 1787.

Indiana Territory was formed in 1800. In 1802, residents petitioned the U.S. Congress to suspend Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance for 10 years but Congress declined. When Indiana Territory reached the second stage of territorial government in 1805, the elected Territorial Assembly enacted legislation allowing inhabitants to convert their slaves to indentured servants; settlers migrating to the area with their slaves could do the same. Records of Knox County clerk (1805-1807) list indentures for men, women, and children lasting from 20 to 99 years. Historian James Madison states

“Growth of antislavery sentiment was sufficient by 1810 to effect repeal of the . . . 1805 law. Yet the status of African Americans remained uncertain even after repeal: indentures made before 1810 remained legal, and the masters of newly arriving African Americans continued to bind them to service in ways that approached the grim reality of slavery. Whether as slave property or as indentures with a set term of service, African Americans were bought, sold, and bequeathed in wills throughout the territorial period.”

And despite the 1816 state constitution’s prohibition of slavery, Knox County court records indicate that black slaves and indentured servants continued to be denied their freedom long after 1816.

In 1817, at least seven petitions for freedom are listed in Knox County court records; their cases were continued through at least two terms of court. In July 1818, one young girl, Katy, was discharged; most of the other cases were continued until the October term of court. In fact, the 1820 U.S. Census recorded 190 slaves in Indiana; 118 of those slaves lived in Knox County. Additional research on these habeas corpus cases is beyond the scope of this project.

[4] Jenny, Petition for Habeas Corpus, July 15, 1818, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Hyacinthe Lasselle, Summons for Habeas Corpus, July 15, 1818, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Hyacinthe Lasselle, Return to Summons, August 4, 1818 includes James and Polly Indentures, July 16, 1818, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; James and Polly, Pleas to Return, August 4, 1818, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; James and Polly vs. Hyacinthe Lasselle, Habeas corpus, February 1819, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 248, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Amory Kinney, Certification of Good Moral Character, February 8, 1819, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 262, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Amory Kinney, Commission as Attorney, February 12, 1819, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 271, Indiana State Library, microfilm; “A. Kinney,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun & General Advertiser, April 24, 1819, 2; James and Polly, Persons of Color v. Hyacinthe Lasselle, Habeas Corpus Case Dismissed, May 11, 1819, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 297, accessed Indiana State Library, microfilm; Hyacinthe Lasselle, Summons for Habeas Corpus, January 27, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Hyacinthe Lasselle, Return to Summons, January 28, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Joseph Huffman, Warrant for Arrest, January 28, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Hyacinthe Lasselle, Complaint against Huffman, February 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Joseph Huffman, Indictment for Harboring a Servant Girl, February 10, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 386, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Knox County Grand Jurors to Joseph Huffman, Indictment, February 10, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; State of Indiana vs. Hyacinthe Lasselle, Habeas Corpus, February 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 429, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Polly v. Lasselle, Habeas Corpus and Frances Jackson v. Francoise Tisdale, Habeas Corpus, May 1, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, 1817-1820, 434-35, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Cauthorn, Brief Sketch, 28, 29; Riker, Executive Proceedings, 124, 133; 1820 United States Census, Vincennes, Knox County, Indiana, roll M33_14, pp. 84, 86, 86A, accessed AncestryLibrary.

Polly Strong’s pursuit of freedom in the Knox County Circuit Court began July 15, 1818 in Vincennes when her enslaved mother, Jenny, with attorney, Moses Tabbs, asked the Court for a writ of habeas corpus. This action forced “prominent citizen” and keeper of Vincennes “principal hotel,” Hyacinthe Lasselle, to bring Polly and her brother James to court and show why Polly and James should remain enslaved.

Lasselle argued that he legally held Polly as a slave because her mother, Jenny, was purchased as a slave from the American Indians prior to the Northwest Ordinance (1787). Moses Tabbs replied that Polly had been born after the Northwest Ordinance was enacted and was therefore free. The parties appeared before Judge Thomas Blake on August 4, 1818. At this time, Lasselle produced indentures for both Polly and James. The indentures, signed July 16, 1818, claimed that each sibling had been “contentedly in employment” of Lasselle “until present time, when I am taught and induced to believe I am free.” The indentures supposedly demonstrated freely given consent by stating that each wanted “to make a just retribution & compensation by my services for the care & attention he [Lasselle] has bestowed upon me. . . .” James’ indenture was to be for four more years; Polly’s was to be for twelve more years. Moses Tabbs argued that both indentures had been signed while the subjects were imprisoned and threatened by Lasselle. The case appears to have been continued to later terms of the Circuit Court and finally dismissed by James and Polly in May 1819.

Attorney Amory Kinney moved to Vincennes from New York in 1819. Knox County Court records show that he was admitted to practice law in the circuit courts of Indiana on February 12, 1819. In January 1820, Polly with attorney Amory Kinney again began proceedings to obtain her freedom. Kinney reiterated the earlier argument that Article VI of the 1787 Northwest Ordinance prohibited slavery in the territory northwest of the Ohio River. Polly, who was born in the territory after 1787, should therefore be free. The Circuit Court continued Polly’s case until the May 1820 term.

Also, in January 1820, Polly was the subject of another case involving Hyacinthe Lasselle. In this case, Lasselle sued Joseph Huffman, a black Vincennes barber, for lost wages claiming that Huffman had harbored Polly and kept her from her work for 19 days. A decision in this court action has not been located.

Polly’s habeas corpus case finally came to trial on May 1, 1820. Her case was combined with that of another Vincennes slave, Francis Jackson. Their cases were similar and their attorneys had agreed to try them together. According to the 1820 U.S. Census for Knox County, one of the three circuit court judges hearing the case owned slaves.

[5] Polly v. Lasselle, Habeas Corpus, and Frances Jackson v. Francoise Tisdale, Habeas Corpus, May 1, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 434-35, Indiana State Library, microfilm; R. Buntin, Clerk, Knox County Circuit Court, True Transcript of Cause, Polly vs. Lasselle, to H. P. Coburn, Clerk, Indiana Supreme Court, Filed May 31, 1820, Indiana State Archives, photocopies; Paul Finkelman, “Almost a Free State,” 64-95.

The Circuit Court made its decision about Polly and Francis based on two facts: the mothers of Polly and Francis were living in the territory northwest of the Ohio River prior to Virginia’s cession of the territory to the United States in 1783; both Polly and Francis were born after the 1783 Cession and after the Northwest Ordinance was enacted in 1787. The court then had to decide if Article VI of the 1787 Ordinance freed the mothers and/or if it freed Polly and Francis.

The court determined that both mothers were held legally as slaves under the laws of Virginia and that the Northwest Ordinance could not emancipate a slave legally held by prior law. In fact, the court determined that liberating the mothers “would be not only contrary to the spirit of all our laws but would be in open violation of the constitution of the United States which makes private property inviolable.”

The Circuit Court also ruled that Polly and Francis, as the children of legal slaves, were also legally enslaved. “In all states where slavery is tolerated and people of color are held as property, this is undeniably the fact. . . . I know of no reason why it should not be the case here for as regards the situation of the mothers of the present applicants, this is now a slave state. . . .”

The Court reasoned that both mothers were enslaved prior to 1787, and that the children of enslaved women were legally enslaved also. The right of the slave owner to maintain his property superseded Article VI of the Northwest Ordinance and Article XI of the 1816 Indiana Constitution.

[6] Polly v. Lasselle, Habeas Corpus, Appeal filed May 12, 1820, Knox Co. Circuit Court Order Book, 1817-1820, 462, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Polly v. Lasselle, Appeal bond, May 12, 1820, Knox County Circuit Court Case Files; Polly vs. Lasselle, Appeal from Knox, Indiana Supreme Court Order Book, 1A, 218, 231; Polly vs. Lasselle, Opinion, July 22, 1820, Indiana Supreme Court Order Book 1A, 235-38, Indiana State Archives, microfilm; Francis Jackson vs. Francoise Tisdale, Appeal from Knox County, July 24, 1820, Indiana Supreme Court Order Book 1A, 244, Indiana State Archives, microfilm; Polly v. Lasselle, Clerk’s fees of the Supreme Court Commencing November Term 1819, Court Record of John Gibson, Ledger No. 2, Vincennes, 1801-1820, photocopy, Indiana State Archives; Hyacinthe Lasselle vs. Polly, Preacipe [sic], to Henry P. Coburn, Clerk, Indiana Supreme Court, July 27, 1820, Lasselle Family Collection, Manuscripts and Rare Books Division, Indiana State Library, microfilm 00523; Hyacinthe Lasselle v. Polly, Assignment of Errors, July 27, 1820, Lasselle Family Collection, Manuscripts and Rare Books Division, Indiana State Library, microfilm 00517; Hyacinthe Lasselle to William Heberd, Express to Corydon, July 27, 1820, Lasselle Family Collection, Manuscripts and Rare Books Division, Indiana State Library, microfilm 00514; “Supreme Court,” Indiana Centinel, August 5, 1820, 3; Francis Jackson vs. Francoise Tisdale, November 12, 1820, Indiana Supreme Court Order Book 1A, 284, 301, Indiana State Archives, microfilm; Francis Jackson vs. Francoise Tisdale, May 8, 1821, Indiana Supreme Court Order Book 1A, 326, 328, Indiana State Archives, microfilm; Polly vs. Lasselle, Damages, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book C, April 1821-June 1825, 33, 42-44; Polly vs. Lasselle, Damages, October 10, 1821, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book C, April 1821-June 1825, 85, 129; Polly Strong, Receipt, April 9, 1822, Lasselle Family Collection, Manuscripts and Rare Books Division, Indiana State Library, microfilm 00602; Isaac Blackford, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Judicature of the State of Indiana vol. 1 (Indianapolis, IN: 1830): 60-63, accessed at Google.com; Dani Pfaff, Research Manager, Indiana Historical Bureau to Elizabeth Osborn, Assistant to Chief Justice for Court History and Public Education, Indiana Supreme Court, e-mail, November 3, 2010.

Polly Strong filed an appeal to the Indiana Supreme Court on May 12, 1820. Frances Jackson also appealed the decision to the Indiana Supreme Court. Indiana Supreme Court Justice John Scott, in his decision, cited the 1816 Indiana Constitution. “In the first article of the constitution, sec. 1 it is declared ‘That all men are born equally free and independent, and have certain natural, inherent and unalienable rights. . . . ‘” Justice Scott continued: “In the 11th article of that instrument, sec. 7, it is declared that ‘There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in this State. . . . It is evident that by these provisions, the framers of our constitution intended a total and entire prohibition of slavery in this State; and we can conceive of no form of words in which that intention could have been more clearly expressed.’” The Court ordered Lasselle to pay the fees and expenses of the trial amounting to $26.12.

But by July 27, 1820, Lasselle had begun preparations to appeal the Indiana Supreme Court’s decision to the U.S. Supreme Court. The documents for such an appeal are located in Lasselle’s personal papers housed at the Indiana State Library. No additional information about this effort has been located. In April 1821, Polly sued Lasselle in the Knox County Circuit Court for $500 in damages. On August 13, 1821, attorney Amory Kinney received $10 from Lasselle for his fees in Polly’s case. In October, a Knox County jury decided in Polly’s favor that Hyacinthe Lasselle owed her $25.16 2/3 plus the costs of this trial. Lasselle’s personal papers show that Polly finally received a payment from him on April 9, 1822.

While Polly was liberated by the court’s decision, Francis Jackson’s appeal for freedom was inexplicably continued to the next term of court and then the next term as well. Finally, on May 8, 1821, the Indiana Supreme Court recognized that Francis Jackson’s case “was an agreed case involving the same points which were decided at the last July term of this court in the case of Polly against Lasselle.” Jackson was finally freed. No explanation for the delay has been located.

[7] Habeas Corpus suits listed in Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, May 1817-December 1820, 32, 37, 62, 63, 104, 158-59, 179, 196, 217, 257, 271, 306, 357-60, 396, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Habeas Corpus suits listed in Knox County Circuit Court Order Book, 1821-1825, 73, 84, 85, 93, 120, 174, 185, 252, 272, 311, 316-17, 316-17, 322; R. J. Walker, Reporter of the State, “Harry and Others vs. Decker & Hopkins,” Reports of Cases Adjudged in the Supreme Court of Mississippi (Natchez, MS: Courier and Journal Office, 1834), 36-43 accessed at USGENWEB Archives Project, Court Cases; “Negro Woman and Child,” [Vincennes, Ind.] Western Sun, February 15, 1817, 2; “For Sale a Likely Negro Woman,” Indiana Centinel, October 16, 1819, 3; “$40 Reward,” Indiana Centinel, August 11, 1821, 4; $50 Reward,” Western Sun and General Advertiser, October 1, 1825, 2; Earl E. McDonald, “Disposal of Negro Slaves by Will in Knox County, Indiana,” Indiana Magazine of History 26, no 2 (June 1930): 143-46, accessed at Indiana Magazine of History Online Resources; Thornbrough, Negro in Indiana, 27-30; Merrily Pierce, “Luke Decker and Slavery: His Cases with Bob and Anthony, 1817-1822,” Indiana Magazine of History, 85, no. 1 (March 1989): 31-49, accessed at Indiana Magazine of History Online Resources; Paul Finkelman, An Imperfect Union, Slavery, Federalism, and Comity (Union, NJ: The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd., 2000), 188, 228-29; Finkelman, “Almost a Free State,” 75-79, 85-89; Indiana State Level Results 1830, Historical Census Browser, University of Virginia, Geospatial and Statistical Data Center accessed http://mapserver.lib.virginia.edu/.

Knox County Court records provide evidence of the efforts of enslaved and indentured African Americans to gain their freedom. Research in Knox County Court records shows habeas corpus cases being heard well into 1823. Slaves had escaped from their owners since the first slave ships arrived in the colonies; and owners had pursued the return of their property as well. Author Merrily Pierce describes five years of attempts by Knox Co. slave owner, Luke Decker, to recapture Bob and Anthony via courts in Orange, Pike, and Jefferson counties. Pike County judges finally ruled, in 1822, that both men were free—well after the Indiana Supreme Court had ruled on slavery (1820) and involuntary servitude (1821).

Ironically, in June 1818, the Mississippi Supreme Court freed three slaves who had been removed from Indiana in July 1816 by another member of the Decker family. The Mississippi Court ruled that the Indiana Constitution prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude; and that the constitution approved by Indiana citizens superseded the Virginia Cession and the Northwest Ordinance.

In 1830 in Vincennes, a census ordered by the town Board of Trustees counted thirty-two slaves. The 1830 U.S. Census for all of Indiana recorded only three slaves.

[8] Mary, a Woman of Colour called Mary Clark Against General Washington Johnston, Habeas Corpus, April 14, 1821, Knox County Circuit Court Order Book C, April 1821-June 1825, 79, 84, Indiana State Library, microfilm; Mary Clark vs. General W. Johnston, An Appeal from Knox County, November 6, 1821, Indiana Supreme Court Order Book 1A, 1817-1822, 358, Indiana State Archives, microfilm; Blackford, Reports, 122-26; Madison, Indiana Law, 37; Finkelman, “Almost a Free State,” 75-79, 85-89, accessed Indiana Magazine of History Online Resources.

In Mary Clark’s appeal, the Indiana Supreme court ruled that “This application of Mary Clark to be discharged from her state of servitude, clearly evinces that the service she renders to the obligee is involuntary . . . . The fact then is, that the appellant is in a state of involuntary servitude; and we are bound by the [Indiana] constitution, the supreme law of the land, to discharge her therefrom.”

Slavery and involuntary servitude persisted in Indiana for many more years despite the Indiana Supreme Court’s decisions. According to historians, one cause for this was the ambiguous language in the state constitution. For example, the statement “there shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude” could be interpreted to mean at some point in the future there would be no slavery or involuntary servitude. Additionally, the state constitution did not offer any direction about how to emancipate slaves and servants; nor did the document provide any means to force owners and masters to liberate their slaves and servants.

The Indiana General Assembly did not take up the challenge to liberate the remaining slaves in Indiana. In fact, as time passed, Indiana’s elected state representatives passed increasingly harsh laws that discriminated against African Americans and removed them from important protections of the law. This increasingly racist attitude carried into the 1851 Indiana Constitution in which Article XIII actually prohibited blacks and mulattoes from moving into the state.

Indiana historian James Madison summarizes “Indiana has never been color-blind. For a very long time, the state’s constitution, laws, courts, and majority white voice placed black Hoosiers in a separate and unequal place. White settlers had created a color line in the territorial period and had affirmed it by 1816. . . . Twists and turns brought some legal modifications by the centennial year of 1916, but separation and discrimination, whether legal or extra-legal, were the patterns of public life for African Americans.”

Keywords

African American, Law & Court Case, Women