Location: 3045 W. Vermont St., Indianapolis (Marion County, Indiana) 46222

Installed 2019 Indiana Historical Bureau and the Indiana Medical History Museum

ID#: 49.2019.4

Text

Side One

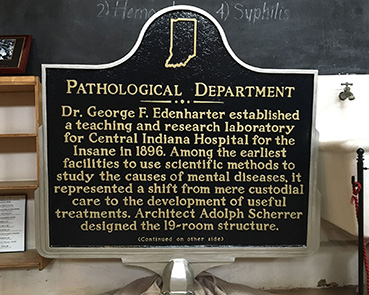

Pathological Department

Dr. George F. Edenharter established a teaching and research laboratory for Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane in 1896. Among the earliest facilities to use scientific methods to study the causes of mental diseases, it represented a shift from mere custodial care to the development of useful treatments. Architect Adolph Scherrer designed the 19-room structure.

Side Two

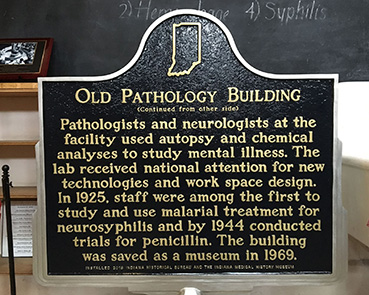

Old Pathology Building

Pathologists and neurologists at the facility used autopsy and chemical analyses to study mental illness. The lab received national attention for new technologies and work space design. In 1925, staff were among the first to study and use malarial treatment for neurosyphilis and by 1944 conducted trials for penicillin. The building was saved as a museum in 1969.

Summary

Visionary Superintendent George F. Edenharter founded Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane’s Pathological Building in 1896. In his American Psychiatry article published the following year, Dr. Albert M. Sterne noted that the “new pathological institute is perfect, ranking far ahead of any similar structure in the United States or Europe which is known to the writer.” Dr. Sterne rightfully anticipated that the groundbreaking lab would contribute to “our knowledge of the etiology and pathology of insanity and the organic nervous diseases so frequently associated with various forms of mental affections.” This progressive work was in stark contrast to the employment of custodial care and moral treatment of mentally ill patients, who were essentially confined to a boarding house. Dr. Lucy Jane King and Alan D. Schmetzer in Dr. Edenharter’s Dream: How Science Improved the Humane Care of the Mentally Ill in Indiana, 1896-2012 noted that this care consisted primarily of “kindly relationships with patients, discussion of their social and psychological problems, purposeful activity, and pleasant surroundings” (3).

Dr. Edenharter hoped to inaugurate a new era of treatment for the mentally ill with the pathological laboratory, by shedding light on how brain structure correlated to mental illnesses. This would inform clinicians’ development of effective treatments. To undertake this task, it was crucial to locate the laboratory on hospital grounds, so that, as stated in the hospital’s 1897 annual report, “By comparing clinical symptoms in a live patient in the wards with his or her later autopsy findings, and accumulating data on many such cases, some idea could be gained of which parts of the brain were associated with what symptoms and which disorders caused what kinds of damage to the brain” (13).

According to Dr. Edenharter’s Dream, pathologists Dr. Walter Bruetsch’s and Dr. Max Bahr’s pioneering malarial studies, conducted from the 1920s to the 1940s, were “among early investigators in the United States to study the first effective treatment for a specific psychiatric disorder” (26). Dr. Bruetsch and Dr. Bahr used malaria to treat paralysis caused by neurosyphilis. They inoculated neurosyphilitic patients with malaria, which induced a fever that destroyed paresis germs. The comparatively-successful treatment of these patients—who would otherwise be permanently relegated to mental hospitals—garnered the pathological lab national and international recognition, including praise from the U.S. Public Health Service Council and German Psychiatric Association. The department further contributed to the field by shipping inoculated blood to institutions across Indiana and the Midwest. In the 1940s, the National Research Council tasked the pathological lab with comparing penicillin with malarial treatment to treat neurosyphiltic paralysis because “this institution had the largest case material treated with malaria alone, and which had been carefully observed from a clinical, serological and histologic point of view for more than 20 years” (Bruetsch, “Penicillin or Malaria Therapy?”). The hospital’s 1937 annual report underlined the importance of this paralytic study: “Without pathologic anatomy general paralysis would be today only another mental disease in which the crumbling of the personality would be attributed very probably to social maladjustments or to other equally theoretical factors, such as disharmony of thoughts, of habits, and of interests” (27).

Insights gained through pathological study moved from the autopsy table to the building’s amphitheater, where free lectures were given to Indiana physicians, as well as students from local colleges (including what would later become the IU School of Medicine). The 1903-1906 Report from the Pathological Department proudly reported that the lab earned a reputation as a “center for scientific investigation, around which members of the profession may assemble and obtain information—both didactic and clinical—at the hands of competent instructors, concerning the diseases with which we deal” (10). Through lectures and participation in laboratory work, IU School of Medicine Professor F. F. Hutchins contended that “These medical men, spreading out over the State, are able to give more efficient service, and become great disseminators of information through the knowledge gained in the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane” (1912 Annual Report, 32). The lab disseminated findings more widely though publications, sent to institutions across the globe, from Oregon State Asylum to Burntwood Asylum in Litchfield, England. These institutions responded with letters praising the lab’s progressive work and noting that it set the standard for the field of mental health.

With the introduction of electroshock therapy (ECT) and antipsychotic medication in the 1940s and 1950s, the value of psychiatric institutions started to diminish. According to Laura M. Bachelder’s “’Inaugurating a Scientific Era,’” in 1969 a group of local physicians and citizens—fearing the possibility of the Pathology Building being razed—established a non-profit organization to preserve the building for its historical significance. At the October 1971 inauguration of what would later be the Indiana Medical History Museum, the Indianapolis Star noted that the building would continue to facilitate the Indiana Neuromuscular Research Laboratory, “making it the oldest existing building still used for medical classrooms in Indiana.” When this research ended in 1988, the building served solely to educate visitors about the vital role played by the Old Pathology Building in advancing knowledge about mental health.

For more information about the pathology lab’s extensive history, see:

- Lucy Jane King, M.D.’s and Alan D. Schmetzer, M.D.’s Dr. Edenharter’s Dream: How Science Improved the Humane Care of the Mentally Ill in Indiana.

- Laura M. Bachelder’s “Inaugurating a Scientific Era:” The Pathological Department, Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane (1896-1996).

Annotated Text

Side one

Dr. George F. Edenharter established a teaching[1] and research laboratory for Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane in 1896.[2] Among the earliest facilities to use scientific methods to study the causes of mental diseases, it represented a shift from mere custodial care to the development of useful treatments.[3] Architect Adolph Scherrer designed the 19-room structure.

Side Two

Pathologists and neurologists at the facility used autopsy and chemical analyses to study mental illness.[4] The lab received national attention for new technologies and work space design.[5] In 1925, staff were among the first to study and use malarial treatment for neurosyphilis and by 1944 conducted trials for penicillin.[6] The building was saved as a museum in 1969.[7]

[1] “Fifty-Second Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane for the Fiscal Year Ending October 31st, 1900,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractors for State Printing and Binding, 1901): 24-26, accessed Indiana State Library (ISL); “Report from the Pathological Department, Central Indiana Hospital for Insane, 1903-1906,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1908): 7, 11, ISL; “Course of Lectures to be Given at the Pathological Department of the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane, Located at Indianapolis, Indiana, 1908-1909,” 2, ISL; “Sixty-Third Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1911,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1912): 15-16, ISL; “Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1912,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1913): 17,21, 24, 29, 31-32, ISL; Lucy Jane King, M.D. and Alan D. Schmetzer, M.D., Dr. Edenharter’s Dream: How Science Improved the Humane Care of the Mentally Ill in Indiana, 1896-2012 (Carmel, IN: Hawthorne Publishing, 2012), 12-13.

[2] “Forty-Eighth Annual Report of the Board of Control and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane, for the Fiscal Year Ending October 31, 1896,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1897): 8, 14, ISL; “A Great Accomplishment,” Indianapolis Sun, December 19, 1896, submitted by applicant; “The Dedication of the Pathological Institute,” Indianapolis Sentinel, December 19, 1896, submitted by applicant; Ludwig Hertoen, M.D., “An Historical Outline of the Methods of Anatomical and Pathological Investigation of the Nervous System,” Indiana Medical Journal 15 (January 1897): 264, accessed Google Books; Albert E. Sterne, M.D., “The New Pathological Institute of the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane,” American Psychiatry (1897): 58, submitted by applicant; Maurice Early, “Indiana Alienist of National Renown Through Efforts to Reduce Insanity,” Indianapolis Star, April 29, 1923, accessed Newspapers.com; Dr. Edenharter’s Dream, 7, 10.

[3] “The New Pathological Institute of the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane,” American Psychiatry (1897): 60, submitted by applicant; “Report from the Pathological Department, Central Indiana Hospital for Insane, 1903-1906,” 10, 13, 27; “Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1912,” 17,21, 24, 29, 31-32, ISL; “Eightieth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1928,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford Printing Co., Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1928): 26, ISL; “Eighty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1932,” (Indianapolis, Wm. B. Burford Printing Co., Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1932): 16, ISL; “Eighty-Ninth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1937,” 27, 28, ISL; Dr. Edenharter’s Dream, 2, 3, 8.

[4] “The Dedication of the Pathological Institute,” Indianapolis Sentinel, December 19, 1896, submitted by applicant; “Forty-Ninth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane for the Fiscal Year Ending October 31, 1897 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1898): 13, ISL; “Report from the Pathological Department, Central Indiana Hospital for Insane, 1903-1906,” 10, 11, 30, 31; Dr. Edenharter’s Dream, 14-15.

[5] “A Great Accomplishment,” Indianapolis Sun, December 19, 1896, submitted by applicant; “The New Pathological Institute of the Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane,” American Psychiatry (1897): 58, 61, submitted by applicant; “Sixty-Third Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1911,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1912): 15; “Sixty-Fourth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1912,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1913): 16, 18, 24, 26, ISL; Dr. Edenharter’s Dream, 4, 13-14, 31, 33.

[6] “Seventy-Seventh Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central Indiana Hospital for Insane at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending September 30, 1925,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1925): 23; Max A. Bahr, M.D. and W. L. Bruetsch, M.D., “Two Years’ Experience with the Malarial Treatment of General Paralysis in a State Institution: Clinical, Serological and Autopsy Observations in 100 Cases,” (1928): 715-727, submitted by applicant; “Eighty-Fifth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1933,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford Printing Co., Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1933): 25, ISL; “Eighty-Ninth Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1937,” 20-21, 25; “Ninety-First Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1939,” (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford Printing Co., Contractor for State Printing and Binding, 1939): 28, 30, ISL; “Ninety-Third Annual Report of the Board of Trustees and Superintendent of the Central State Hospital at Indianapolis, Indiana for the Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 1941,” (Indianapolis: C. E. Pauley & Co., Inc.): 21, ISL; Reprint, Walter L. Bruetsch, M.D., “Penicillin or Malaria Therapy in the Treatment of General Paralysis? (A Clinico-Anatomic Study),” Diseases of the Nervous System (December 1949), submitted by applicant; Philip M. Coons, M.D., and Elizabeth S. Bowman, M.D., Psychiatry in Indiana: The First 175 Years (Bloomington, IN: iUniverse, Inc., 2010), 14; Dr. Edenharter’s Dream, 26-27.

[7] Certificate of Incorporation, Indiana Medical History, Inc., (Secretary of State, State of Indiana), December 29, 1969, submitted by applicant; Charles A. Bonsett, M.D., “The Old Pathology Building—Hoosier Medicine’s ‘Little Red Schoolhouse,’” Journal of the Indiana State Medical Association 64, no. 9 (September 1971): n.p.; “Rededication Set for State’s First Medical Center,” Indianapolis Star, October 3, 1971, accessed Newspapers.com; “The Mystery Artist of Indianapolis,” Indianapolis Star, October 7, 1971, accessed Newspapers.com; “124th Annual Report, Central State Hospital, July 1, 1971 to June 30, 1972,” iii, ISL; Laura M. Bachelder, Oren S. Cooley, ed.,“Inaugurating a Scientific Era,” The Pathological Department, Central Indiana Hospital for the Insane (1896-1996), accessed imhm.org; Dr. Edenharter’s Dream, 33.

Keywords

Science, Medicine, and Technology