Location: Gazebo Park, Whitewater Canal State Historic Site (near lock #25), 19083 Clayborn St., Metamora (Franklin County), Indiana 47030

Installed 2017 Indiana Historical Bureau, Indiana Audubon Society, Indiana Department of Natural Resources, and Indiana State Museum and Historic Sites

ID#: 24.2017.1

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn more about the passenger pigeons' extinction.

Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn more about the passenger pigeons' extinction.

Text

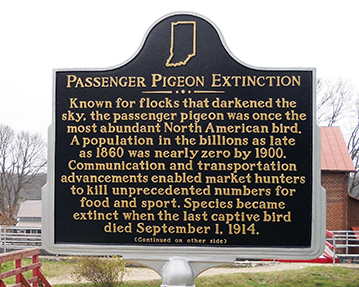

Side One

Known for flocks that darkened the sky, the passenger pigeon was once the most abundant North American bird. A population in the billions as late as 1860 was nearly zero by 1900. Communication and transportation advancements enabled market hunters to kill unprecedented numbers for food and sport. Species became extinct when the last captive bird died September 1, 1914.

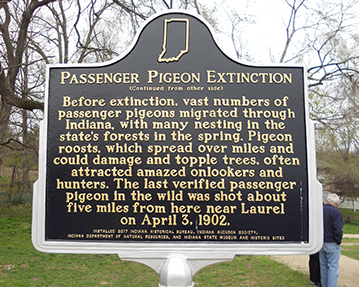

Side Two

Before extinction, vast numbers of passenger pigeons migrated through Indiana, with many nesting in the state’s forests in the spring. Pigeon roosts, which spread over miles and could damage and topple trees, often attracted amazed onlookers and hunters. The last verified passenger pigeon in the wild was shot about five miles from here near Laurel on April 3, 1902.

Annotated Text

Side One

Known for flocks that darkened the sky[1], the passenger pigeon was once the most abundant North American bird.[2] A population in the billions as late as 1860 was nearly zero by 1900.[3] Communication and transportation advancements enabled market hunters to kill unprecedented numbers[4] for food[5] and sport.[6] Species became extinct when the last captive bird died September 1, 1914.[7]

Side Two

Before extinction, vast numbers of passenger pigeons migrated through Indiana, with many nesting in the state’s forests in the spring. [8] Pigeon roosts, which spread over miles and could damage and topple trees, often attracted amazed onlookers and hunters.[9] The last verified passenger pigeon in the wild was shot about five miles from here near Laurel on April 3, 1902. [10]

[1] James J. Audubon, Ornithological Biography or An Account of the Habits of the Birds of the United States of America (Edinburgh: Adam Black, 1831), 321 accessed Biodiversity Heritage Library; W.H. Davenport Adams, The Hunter and the Trapper in North America or Romantic Adventures in Field and Forest From the French of Bénédict Henry Révoil (London: T. Nelson and Sons, Paternoster Row, 1874), 126, accessed Biodiversity Heritage Library; Major W. Ross King, The Sportsman and Naturalist in Canada or Notes on the Natural History of the Game, Game Birds, and Fish of that Country (London: Hurst and Blackett, Publishers, 1866), 121, accessed Biodiversity Heritage Library; “Wild pigeons in multitudinous numbers…” Indianapolis Star 14 September 1864, 3 accessed newspapers.com; “Immense Flock of Pigeons,” Indiana Herald [Huntington, Indiana], 1 March 1854, 3 accessed newspapers.com; Joel Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky: The Passenger Pigeon’s Flight to Extinction (New York: Bloomsbury, 2014), 46-56.

Several writers and ornithologists recorded observations of pigeon flocks so large that they blocked out the sun. James J. Audubon, a prominent ornithologist, observed a large passenger pigeon flock along the Ohio River on his way to Louisville, Kentucky in 1813. He recalled, “The air was literally filled with pigeons; the light of noon-day was observed as by an eclipse.” Bénédict Henry Révoil saw a similar flight of pigeons in 1847 near Hartford, Kentucky. As he walked, he noticed “that the horizon was darkling; and, after having attentively examined what could have caused so sudden a change in the atmosphere, I discovered that the clouds-as I had supposed them to be-were neither more nor less than numerous enormous flocks of pigeons.” Major W. Ross King observed a “grand migration of the Passenger Pigeon” while at Fort Mississauga in Ontario, Canada in 1860. He wrote “I was perfectly amazed to behold the air filled and the sun obscured by millions of pigeons.” Newspaper accounts also attest to large flocks that blockd the sun. In 1854, the Indiana Herald reported on pigeon flights in Franklin County, Indiana that “darken the heavens.” The Indianapolis Star noted in 1864 that near Greensburg, Indiana “wild pigeons in multitudinous numbers are now flying about. The sky yesterday morning was darkened with them, although the glorious sun was rolling himself up in all his pristine and vigorous original effulgence.” For an overview of accounts of massive pigeon flocks, including those that date to the colonial era, see Joel Greenberg’s A Feathered River Across the Sky, pages 46-56.

[2] A.W. Schorger, The Passenger Pigeon: Its Natural History and Extinction (Madison, Wisconsin: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1955), 199-204; Chih-Ming Hung, Pei-Jen L. Shaner, Wei-Chung Liu, Te-Chin Chu, Wen-San Huang, and Shou-Hsien Li, “Drastic population fluctuations explain the rapid extinction of the passenger pigeon,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Science vol. 111, no. 29 (July 22, 2014): 1 accessed http://www.pnas.org; Susan Milius, “Passenger Pigeon had ups, downs,” Science News vol. 186. no. 3 (August 9, 2014), 17 accessed JSTOR; Joel Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, 1; Joshua W. Ellsworth and Brenda C. McComb, “Potential Effects of Passenger Pigeon Flocks on the Structure and Composition of Presettlement Forests of Eastern North America,” Conservation Biology vol. 17 no. 6 (December 29, 2002): 1551; Christal Pollock, “The Passenger Pigeon,” Journal of Avian Medicine and Surgery vol. 17 vo. 2 (June 2003): 97 JSTOR; Sara L. Webb, “Potential Role of Passenger Pigeons and Other Vertebrates in the Rapid Holocene Migrations of Nut Trees,” Quaternary Research vol. 26 no. 3 (November 1986): 370; Alexander Wilson, American Ornithology or The Natural History of the Birds of the United States, Volume V (Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep, 1812), 106-108, accessed Internet Archive; Adams, The Hunter and the Trapper in North America, 126; King, The Sportsman and Naturalist in Canada, 121-122.

A.W. Schorger decided that “it is an insuperable problem to determine the total population of the passenger pigeon at any one time,” since there is no data set available detailing all the passenger pigeon nestings in a given year. However, the wide distribution of nestings recorded in newspapers, journals, and books indicate that the entire continental population of the passenger pigeon was never in one place, but spread out over North America. Schorger cites several recorded sightings of giant flocks numbering over a billion passenger pigeons (see next paragraph) to illustrate that population of the passenger pigeons was 3,000,000,000 to 5,000,000,000 from the 16th to early 19th centuries, making the bird 25-40 percent of the total bird population of the United States. A recent study headed by Chih-Ming Hung published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences that used DNA taken from the toe pads of three museum specimens of passenger pigeons suggests that passenger pigeon population was “persistent at approximately 10^5 throughout the last million years, this species probably experienced frequent and dramatic populations fluctuations following climatic, food-resource, and other ecological variations, thereby increasing in its extinction risk. We suggest that before human settlement the passenger pigeon routinely recovered from population lows.” However, the study charts populations over vast periods of time, not decades. Therefore the study does not dispute huge populations of pigeons recorded during the 19th century and still accepts that “The passenger pigeon was once the most abundant bird in the world, with a population size estimated at 3-5 billion in the 1800s.” Other historians, naturalists, and scientists have accepted Schorger’s calculations, as well as the assessment that it was once the most populous bird. See Joel Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, Joshua W. Ellsworth and Brenda C. McComb, “Potential Effects of Passenger Pigeon Flocks on the Structure and Composition of Presettlement Forests of Eastern North America,” Christal Pollock, “The Passenger Pigeon,” and Sara L. Webb, “Potential Role of Passenger Pigeons and Other Vertebrates in the Rapid Holocene Migrations of Nut Trees.”

Ornithologists and naturalists recorded several observations of massive flocks of passenger pigeons during 19th century. Alexander Wilson estimated a flock of pigeons he witnessed near Frankfort, Kentucky in the early 1800s to include 2,230,272,000 pigeons by calculating the number of pigeons per square yard contained in the entire distance of the flock. W.H. Davenport Adams witnessed a flock in 1847 in Hartford, Kentucky and calculated it to include 1,120,140,000 birds using similar methods to Wilson. Major W. Ross King calculated the flock of pigeons he saw at Fort Mississauga in Ontario in 1860 to be three hundred miles long and a mile wide, flying at sixty miles per hour. Schorger calculated this flight would include 3,717,120,000 pigeons.

[3]A.W. Schorger, The Passenger Pigeon, 199-204, 222-223; Adams, The Hunter and the Trapper in North America, 137; King, The Sportsman and Naturalist in Canada, 121-122; “Natural History: Former Abundance of the Wild Pigeon,” Forest and Stream vol. 17 no. 1 (October 27, 1881), 246 accessed ProQuest; Ruthven Dean “Additional Records of the Passenger Pigeon in Illinois and Indiana,” The Auk vol. 12 no. 3 (July 1895): 298-300, accessed JSTOR; C.F. Hodge “The Passenger Pigeon Investigation,” The Auk vol. 28 no. 1 (January 1911): 49-53 accessed JSTOR; “To Save the Passenger Pigeons,” Forest and Stream 74 (January 29, 1910): 172 accessed ProQuest; C.F. Hodge, “A Last Word on the Passenger Pigeon,” The Auk vol. 29, no. 2 (April 1912): 169-175 accessed JSTOR. Amos Butler, “Further Notes on Indiana Birds,” Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science vol. 22 (1912): 63, accessed https://journals.iupui.edu; Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, xii, 5; Erroll Fuller, The Passenger Pigeon (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2015), 56-60.

A.W. Schorger estimated the passenger pigeon population in North America conservatively from three to five billion pigeons from roughly the 16th century through the early 19th century using historical accounts of pigeon flocks (see footnote 2). Starting in the latter half of the 19th century, pigeon population decreased rapidly. More reports surfaced warning of the bird’s rapid decline, instead of its abundance. Bénédict Henry Révoil predicted, after witnessing a pigeon massacre in Kentucky in 1847, “This variety of game [passenger pigeons] is, in America, threatened with destruction…if the world endure a century longer, I will wager that the amateur of ornithology will find no pigeons except in select Museums of Natural History.” One of the last recorded flight of passenger pigeons in the billions came from Major W. Ross King at Fort Mississauga in Ontario in 1860. In 1881, Forest and Stream reported on the “Former Abundance of the Wild Pigeon,” noting, after reviewing earlier 19th century accounts of flocks in the billions, like Alexander Wilson’s (see footnote 2) that “The time has passed when any such vast bodies of migrating birds as were observed when Wilson and Audubon can be seen. In the Eastern States the Passenger Pigeon is now not a very common bird, and in many sections its nest is regarded as a rare and desirable find.” Likewise, ornithologist Ruthven Deane noted in 1895 in his article on passenger pigeons in Illinois and Indiana that “the occurrence of the Wild Pigeon (Ecopistes migratorius) in this section of the country, and in fact throughout the west generally, is becoming rarer every year” and that “large flocks of Passenger Pigeons are a thing of the past.” Ornithologists worried the bird was on its way to extinction during the early 1900s. In 1910, Forest and Stream published a list of cash awards upwards of $500 from ornithologists to the individual that could bring them to a passenger pigeon nest or colony. C.F. Hodge reported on the progress of the “search for this lost species” in The Auk in 1911, noting that as of yet no confirmed passenger pigeons had been seen, but many mourning doves, who had a similar appearance. In 1912, C.F. Hodge issued a final report on the search in 1912, and reported that “the final result is: no nestings reported, and there are no undecided cases and no disputes.” Ornithologist Amos Butler concluded in 1912 that “The Passenger Pigeon is probably now extinct,” since the rewards had gone unfulfilled.

Several secondary sources note that after 1860, the population of the passenger pigeon began to decline with dramatic reductions during the 1870s. Joel Greenberg accepts the 1860 flight of at least a billion pigeons seen by Major W. Ross King in Ontario as one of the last of such flights to occur. Erroll Fuller notes that commentary on decline of the passenger pigeon began in the 1850s, but during the 1860s it became more apparent the bird could be in danger, and after 1870, the passenger’s pigeon’s numbers decreased dramatically.

[4]Jennifer Price, Flight Maps: Adventures with Nature in Modern America (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 4, 18; Schorger, Passenger Pigeon, 144-156; Greensberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, 80-81, 192-193; H.B. Roney, “Among the Pigeons,” Chicago Field vol.10 (January 11, 1879): 271; E.T. Martin, “The Pigeon Butcher’s Defense: A Reply to Professor Roney’s Account of the Michigan Nestings of 1878,” Chicago Field vol. 10 (January 25, 1879): 385-386; William Brewster, “The Present Status of the Wild Pigeon (Ectopistes migratorius) as a Bird of the United States, with Some Notes on Its Habits,” The Auk vol 6. no. 4 (October 1889): 285-291, accessed JSTOR; “Game Bag and Gun: Netting Wild Pigeons,” Forest and Stream vol. 43 no. 2 (July 14, 1894): 2 accessed ProQuest; “Several tons of Railroad Pigeons…” State Indiana Sentinel 8 May 1851, 3 accessed newspapers.com; Lisa Mighetto, Wild Animals and American Environmental Ethics (Tucson, Arizona: University of Arizona Press, 1991), 28-29; Stanley E. Hedeen, “From Billions to None: Destruction of the Passenger Pigeon in the Ohio Valley,” Ohio Valley History vol. 10 no. 3 (Fall 2010): 27-28.

A.W. Schorger and Jennifer Price, historians of passenger pigeon extinction tie transportation advancements made in the 18th and 19th centuries to the demise of the bird. Price traces various transportation advances and how each affected the pigeon trade in Flight Maps. Price observes, “As early as the 1750s, pigeons already had become scarce on the eastern seaboard. New and improved roads, canals, and eventually railroad lines rapidly expanded the markets west. Game depletions followed in the wake of new transport routes.” However, the railroad really expanded the pigeon trade because it could get the birds from rural locations to large eastern markets fast. Price emphasizes, “Since the 1860s, as the rapid westward expansion of rail lines linked the still-rich game hunts of the rural Midwest to the fast-burgeoning eastern cities, market hunters had been harvesting game in unprecedented numbers.” Schorger also emphasizes railroads, noting that “the trade in pigeons did not become important until the railroads offered rapid transportation to the city markets.” Expanded rail lines meant buyers and trappers from large commission houses could follow pigeons year round.

Joel Greenberg links both transportation, as well as communication advancements, namely the railroad and telegraph, to passenger pigeon extinction. Before the railroad, game dealers could bring pigeons to local markets, but had no way of shipping their goods to large, eastern markets. National markets rose as the railroad expanded westward into pigeon range and linked major markets to rural areas where pigeons could still be found. Greenberg states “Birds from the most remote reaches of pigeon range could be transported to rail lines…The expanding coverage of telegraph wires made pigeons even more vulnerable, since a large gathering of birds not only would draw attention of the locals, but would soon bring people from far and wide. The agents who staffed the rails made it their business to spread the word.”

Two accounts of market pigeon hunting at the same vast pigeon nesting in Petoskey, Michigan in 1878 published in the Chicago Field reveal how damaging market hunting fueled by faster transportation and communication was to the passenger pigeon population. Since Edward T. Martin, a known pigeon game dealer wrote one account and Professor H.B. Roney, a game protectionist, wrote another, the two accounts balance one another out. Roney attested that “large numbers of professional ‘pigeoners,’ as they term themselves, devote their whole time to the business of following up and netting wild pigeons for gain and profit.” Hunters used nets six feet wide and thirty feet long to capture large numbers of pigeons at a time. Roney noted that each pigeoner caught on average sixty to ninety dozen pigeons a day per net used. Prices ranged from thirty-five cents to forty cents per dozen dead birds at the nesting site and rose to sixty cents at city markets. Live birds could be bought for $1-2 per dozen, making pigeon hunting a rather lucrative business. Roney reported that wagon loads of dead and live birds were hauled to the train station or steam ships from the nesting site. Regular shipments by rail amounted to sixty barrels of dead pigeons per day. Roney reviewed hotel registries that indicated hunters came from New York, Wisconsin, Pennsylvania, Michigan, Maryland, Iowa, Virginia, Ohio, Texas, Illinois, Maine, Minnesota, and Missouri, many of whom arrived via train to the site. In total, Roney estimated 1,000,000,000 birds were “sacrificed” (either accidentally killed or shipped either dead or alive to market). Market hunter E.T. Martin disputed the numbers Roney came up with. Martin estimated that the average catch was fifty dozen pigeons per day, as opposed to sixty. Martin provided a table noting the numbers of shipments from Petoskey and nearby Boyne Falls and Cheboygan, which detailed the amounts of birds shipped dead or alive by express and by boat. Martin estimated only 1,500,000-2,250,000 birds were caught or killed.

Other sources support the importance of rail and communication advancements. William Brewster reported on the nature of market pigeon hunting after interviewing with veteran pigeon hunters, namely S.S. Stevens of Cadillac, Michigan in 1888 in an article in The Auk. Stevens said that forty to fifty dozen birds caught per net was considered a good catching, but sometimes only ten or twelve dozen per net were caught. During another vast nesting near Petoskey in 1881, Stevens witnessed five hundred men netting pigeons, each capturing an average of 20,000 pigeons. He testified that two car loads of birds were shipped south by rail each day at that nesting over a five week span. Though Stevens did not mention communication, Brewster indicated the importance of communication methods for hunters to find pigeon nestings nationwide; when Brewster and his party failed to find a large nesting colony, they worried it was because the birds had flown “beyond the reach of mail and telegraphic communication.” Forest and Stream also commented on the importance of a communication network for the hunters. In 1894, an article noted “A very good system has been established for keeping track of them [the pigeons], which is specially looked after by the different express companies and the shippers and handlers of live and dead birds…When the body of the birds leaves the South, the local superintendents of the express companies are instructed to keep their eyes out for indications of a nesting and the messengers generally are to report on their route.”

Newspapers contain abundant notes regarding the number of passenger pigeons shipped by rail. For example, the State Indiana Sentinel reported May 8, 1851 that seven tons of wild pigeons had arrived in New York City via the Erie Railroad, from Steuben and Alleghany [sic] counties in Pennsylvania and sixty-five tons had been brought since the first of April. Schorger built tables from data in newspaper articles from the Grand Rapids, Michigan Eagle, the Portage, Wisconsin Register, La Crosse, Wisconsin Chronicle, the Milwaukee Evening Wisconsin, and others note that the amount of pigeons shipped and the value from various large nestings in those states that highlight the importance of the rail road toward facilitating the pigeon game market.

Several other scholars attribute rapid deforestation in North America during the 19th century to passenger pigeon extinction (see Lisa Mighetto, Wild Animals and American Environmental Ethics, Stanley E. Hedeen, “From Billions to None: Destruction of the Passenger Pigeon in the Ohio Valley). However, Greenberg asserts that there were more than enough nut trees that contained mass the pigeons preferred to eat and nest in during the 1880s since the first trees to be cut in the north were pine, not oak, birch, and aspen (prime pigeon forage). Pigeons were also known to eat from other food sources, including wild plants, earthworms, snails, and insects. Greenberg admits that the accelerated loss of forests that occurred into the 20th century certainly would have reduced passenger pigeon population beyond sustainability eventually, but the pigeon did not survive long enough for this to take place because of killing pigeons for profit.

[5]“Pigeon Shooting,” State Indiana Sentinel 21 March 1850, 2 accessed newspapers.com; Roney, “Among the Pigeons,” 345; Advertisement: St. Charles Restaurant, Louisville Daily Courier 28 March 1860, 2 accessed newspapers.com; Charles Ranhofer, The Epicurean: A complete treatise of analytical and practical studies on the culinary art, including table and wine service, how to prepare and cook dishes, etc. and a selection of interesting bills of fare from Delmonico’s from 1862-1894 (New York: R. Ranhofer, 1920), vii-viii, 615-619, 626-629, 654, 688-689, 712, 714, accessed HathiTrust; Price, Flight Maps, 8-16 35-41; Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, 31-35, 68-73.

Nineteenth century market hunters shipped passenger pigeons to markets, where they were often sold to restaurants. Though archaeological remains and historical accounts indicate Native American tribes ate passenger pigeons for food, as well as early European explorers, colonists, and settlers, transportation advancements allowed pigeon meat to be shipped across country and sold at large markets in Chicago, New York, and other cities (see footnote 4). An article in the State Indiana Sentinel attests to the palatability of passenger pigeons during the 19th century. After reporting on a shooting at a large pigeon roost outside of Lafayette, Indiana, at which hunters returned to town with 598 pigeons, the article encouraged readers to head to the pigeon roost to get their own pigeons because “the pigeons are unusually fat, and most excellent eating.” An 1860 advertisement in the Louisville Daily Courier for St. Charles Restaurant on Fifth Street noted that Wild Pigeons, along with an assortment of other game, arrived daily at the restaurant. HB Roney remarked in the Chicago Field in 1879 that “in fashionable restaurants they [pigeons] are served as delicious tid-bits at fancy prices.” Charles Ranhofer, former chef of the high society New York City restaurant Delmonico’s and honorary president of the Société Culinaire Philanthropique of New York, included thirty-nine recipes for pigeons in the Epicurean, his book on the culinary arts. The book contains hundreds of recipes “now followed by the principal chefs of France and the United States,” that upper class Americans ate in the late Victorian era. For broader accounts of passenger pigeons as food, as well as further information how the pigeon fit into expanded 19th century markets, see Jennifer Price’s Flight Maps and Joel Greenberg’s A Feathered River Across the Sky.

[6] George Shiras III, Hunting Wild Life With Camera and Flashlight: A Record of Sixty-five Years’ Visits to the Woods and Waters of North America, Volume I (Washington, DC: National Geographic Society, 1935), 123; Price, Flight Maps, 24-26; “Near Tahlequah, Indian Territory,” The Daily Republican [Monogahela, Pennsylvania] 3 December 1886, 2 accessed newspapers.com; “Protecting Wild Pigeons,” Forest and Stream vol. 7 no. 12 (October 26, 1876), 184 accessed ProQuest; “Sporting Notes,” Democrat and Chronicle [Rochester, New York] 28 April 1876, 4 accessed newspapers.com; “Pigeon Roost,” Indiana American [Brookville, Indiana] 3 February 1854, 2 accessed newspapers.com.

George Shiras wrote in his recollections as a field naturalist, nature writer and photographer, and hunter for over sixty-five years that he “witnessed the disappearance of this once countless species,” the passenger pigeon in northern Michigan, Wisconsin, and western Ontario. He wrote that hunting attributed to much of the slaughter of the passenger pigeon as they formed huge nests to breed in this area. Though he had never participated in wholesale hunting of the pigeon, Shiras had seen evidence at pigeon nesting sites, since hunters often built a fire around the nests to smoke out the birds to hunt them easily. Shiras wrote, “In addition to the local hunters, professional trappers from places outside the district were quickly notified of any gathering place, and were soon on hand netting or killing the birds by the hundreds of thousands for the eastern market, besides shipping them alive in vast numbers in crates for trap shooting tournaments at Chicago and other large centers of population.”

According to Jennifer Price, the sport of trapshooting, during which contestants shoot at targets, namely live passenger pigeons launched into the air from traps, contributed to passenger pigeon extinction. The sport began in England in the late 1700s and arrived in the United States by the 1830s. Trapshooting popularized as a pastime for the wealthy during the 1870s and 1880s. Passenger pigeons, which were easily captured by market hunters and shipped by rail to sporting associations, became the preferred target. The Daily Republican reported that numerous people came to a pigeon roost in Tahlequah, Oklahoma that contained “millions of birds,” to engage in “trapping, netting, and killing them for shipment, which they are doing by the thousands.” Trappers from New York, Philadelphia, Chicago, St. Louis and other areas arrived at the roost and sent many live birds East “for shooting matches by sporting clubs.” Forest and Stream reported in “Protecting Wild Pigeons,” in 1876 that nearly a hundred thousand pigeons were shot in New York state alone each year; 12,000 birds had been used in the last state sportsman’s convention, 7,000 had been shot at a Syracuse club a week later. In the same year, the Democrat and Chronicle reported that the Livingston, New York Sportsmen’s associated secured 10,000 live pigeons for their trapshooting event. Other Sportsmen’s associations used similar amounts of birds. For example, an advertisement for the Texas Sportsmen’s association called for 5,000 live pigeons. In addition to trapshooting, local hunters and sportsmen as Shiras mentioned also contributed, albeit in smaller numbers, to the extinction of the passenger pigeon. For example, in 1854 a large pigeon roost formed three miles northwest of Brookville, Indiana. The Indiana American noted that sportsmen from miles around were flocking to Brookville to hunt pigeons. They left the roost with all the pigeons they could carry, “yet they leave hundreds of the dead wounded on the ground.”

[7] D.H. Eaton, “The Last Surviving Passenger Pigeon: One Solitary Specimen Living Out of Countless Millions that Once Darkened the Skies in their Migration,” Forest and Stream vol. 82 no. 6 (February 7, 1914): 165 accessed ProQuest; Albert Hazen Wright, “Martha the Last Passenger Pigeon Dead: The Passenger Pigeon early Historical Records, 1534-1860,” Forest and Stream vol. 83 no. 11 (September 12, 1914): 336 accessed ProQuest; “Martha, the Last Passenger Pigeon, Dead,” New York Times 13 September 1914, D6 accessed ProQuest; Smithsonian Institution, National Museum of Natural History, Division of Birds, Ectopistes migratorius, USNM 223979, 1 September 1914, accessed http://collections.nmnh.si.edu/; Smithsonian Institution, “Martha, a Passenger Pigeon” Photograph, Historic Images of the Smithsonian, Record Unit 7410, Box 1, Folder 4, Smithsonian Institution Archives, Washington, D.C. accessed https://siarchives.si.edu/.

On February 7, 1914, Forest and Stream reported on the “last surviving passenger pigeon” named Martha, who lived at the Cincinnati Zoo. According to the magazine, in 1877 three pairs of passenger pigeons arrived at the zoo, for $2.50 per pair. Beginning in 1878, the birds “continued to breed, until the usual result of close inbreeding became manifest.” By 1910, a male passenger pigeon and Martha were the only ones left. For several years, the Zoo had a reward of $1,500 for a live Passenger Pigeon, but it had gone unfulfilled. On September 12, 1914 Forest and Stream reported that Martha died on September 1, 1914 and her body had been sent to the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. On September 13, 1914, the New York Times likewise reported that Martha, “the only known survivor of that species of pigeon known as the passenger,” had died recently and sent to the Smithsonian. Records documenting specimen USNM 223979, passenger pigeon, at the Smithsonian indicate this specimen is Martha and was collected on September 1, 1914 after donation to the United States National Museum, now the National Museum of Natural History. Though records indicate Martha is not currently on display, a plaque on the case reads “Martha, last of her species, died at 1pm 1 September 1914, age 29, in the Cincinnati Zoological Garden. Extinct.”

[8] William Herbert, A Visit to the Colony of New Harmony in Indiana…recently purchased by Mr. Owen for the establishment of a society of mutual co-operation and community of property:…to which are added, some observations on that mode of society, and on political society at large, also, a sketch for the formation of a co-operative society (London: Printed for G. Mann, 1825), 10; “Pigeons,” Wabash Courier 17 March 1849, 2 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Wild Pigeons are becoming very…” Weekly Republican [Plymouth, Indiana] 10 September 1857, 3 accessed newspapers.com; “During the past week numberless…” Richmond Weekly Palladium 15 September 1868, 3 accessed newspapers.com; “Wild Pigeons are still passing…” Indianapolis News 23 March 1872, 4 accessed newspapers.com; “The Pigeon’s [sic] have, after an…” Weekly Republican [Plymouth, Indiana] 20 May 1858, 2 accessed newspapers.com; Amos W. Butler, The Birds of Indiana: A Descriptive Catalogue of the Birds That Have Been Observed Within the State, With an Account of Their Habits (Indianapolis, Indiana: Department of Geology and Natural Resources, 1898), 761-763.

William Herbert recorded one of the earliest accounts of passenger pigeons migrating through Indiana in September 1823 at Harmony. He wrote “we witnessed some very astonishing flights of pigeons. Such were their numbers, that the literally formed clouds, and floated through the air in a frequent succession of these as far as the eye could reach.” Indiana newspapers reported on presence of the pigeons throughout the state, often in the fall or spring. In March 1848, the Wabash Courier announced that the woods around Evansville, Indiana were full of wild pigeons and that “flock after flock flying across the country each one containing steamboat loads of these birds,” was seen. The Weekly Republican of Plymouth, Indiana indicated in September 1857 that wild pigeons were “becoming very plenty hereabouts” and the Richmond Weekly Palladium noted that in September 1868 “numberless” wild pigeons had flown through the area over the past week. In March 1872, the Indianapolis News noted that “wild pigeons are still passing over in large numbers. We counted nine flocks in less than an hour the other day.”

Ornithologist Amos Butler noted that large flocks of passenger pigeons typically began arriving in southern Indiana during September from the north and appeared again in February and March. Though most went to northern states, like Michigan to nest in large colonies for breeding, some bred in Indiana singly or in colonies. Butler included numerous recollections from individuals in his book The Birds of Indiana (1898) of passenger pigeon nestings. H.D. Johnson, of Franklin County told Butler that during the 1820s he went to a large pigeon nesting to catch squabs (young pigeons that cannot yet fly) in Springfield or Bath Township. Mr. W.W. Pfrimmer of Newton County noted pigeons formerly nested there along the Kankakee River. The Weekly Republican of Plymouth, Indiana reported on a pigeon nesting in Decatur County in 1858 that was approximately twenty eight miles in length and fourteen miles wide. The article noted “every tree has from ten to fifteen nests and every nest at least one bird.”

On extinction, see footnotes 3 and 7.

[9] Herbert, A Visit to the Colony of New Harmony in Indiana, 10; “Immense Flock of Pigeons,” Indiana Herald 1 March 1854, 3 accessed newspapers.com; “Pigeon Roost,” Indiana American [Brookville, Indiana] 3 February 1854, 2, accessed newspapers.com; “There is a pigeon roost…” Weekly Reveille [Vevay, Indiana] 11 April 1855, 3 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Pigeon Shooting,” Crawfordsville Weekly Journal 10 March 1866; 1 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “There is an enormous pigeon…” Fort Wayne Daily Gazette 3 March 1866, 2 accessed newspapers.com; Price, Flight Maps, 8-24; Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, 46-67.

Vast passenger pigeon roosts, or resting sites for the birds, formed throughout the year in North America, including in Indiana. William Herbert observed large flocks of passenger pigeons at his visit to Harmony, Indiana in September 1823. He noted “At that time of the year these birds congregate in the woods of this part of America by millions. Parties are sometimes formed to go to their roosts by night, when by knocking them off the trees with poles, any quantity of them may be taken.” In 1854, a pigeon roost ten miles long by five miles wide formed in Franklin county near Brookville. The Indiana Herald noted that there were so many pigeons roosting in the trees that the ground beneath was “covered to the depth of several inches with their manure.” Additionally, thousands of the birds were “killed by casualties from breaking limbs of trees.” The Indiana American reported that “sportsmen and sportsboys go out about dark with their old fusees, and return in a few hours with all they can carry.” The articled noted “persons are coming many miles to enjoy the sport. Come on.—There are pigeons enough for all.” In 1855, the Weekly Reveille of Vevay announced there was a pigeon roost five miles long and a mile and a half wide on Otter Creek in Ripley county. Two citizens of Lawrenceburg went to the roost and returned with 995 pigeons. Similarly, in 1866 the Crawfordsville Weekly Journal noted that a large pigeon roost in Bedford, Indiana ten miles long and two miles wide caused the trees the birds roosted in to be “literally broken down by the weight of the birds.” The Fort Wayne Daily Gazette reported that this group of pigeons, in nearby Martin county, Indiana that “hunters are having rare time among them…It is a mystery where they all find food enough to keep them in good condition.”

For a broader discussion of massive passenger pigeon roosts, the awe they inspired, and the vast numbers of individuals that hunted pigeons at the roosts in places in United States other than Indiana, including Native American and colonial accounts, see Price, Flight Maps, 8-24 and Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, 46-67.

[10]Greenberg, A Feathered River Across the Sky, 161, 168-173; Schorger, Passenger Pigeon, 286; Amos Butler Dies: Welfare Authority,” Indianapolis Star 6 August 1937, 1, 11 accessed newspapers.com; Amos W. Butler, “Some Rare Indiana Birds,” Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science (1902): 98-99; Amos Butler, “Further Notes on Indiana Birds,” Proceedings of the Indiana Academy of Science (1912): 63-64 accessed https://journals.iupui.edu; “Chas K. Muchmore to Mr. A.W. Butler,” 19 September 1932, Indiana Audubon Society; “Chas K. Muchmore to Mr. Amos W. Butler,” 30 August 1932, Indiana Audubon Society; 1900 United State Federal Census, Laurel, Franklin County, Indiana, roll 372, page 6A, line 4 accessed AncestryLibrary.

Joel Greenberg admits that it is impossible to locate the exact date the last passenger pigeon died in the wild. For historical purposes, Greenberg, the latest historian of the passenger pigeon, advocates that the record of the last passenger pigeon needs to be verified with credible data. In that case, a collected specimen of the passenger pigeon is favorable, however, the endorsement of a “local expert of known repute” who inspected the specimen is also acceptable. This evidence is needed because the passenger pigeon closely resembles the common mourning dove. Before, Greenberg, A.W. Schorger determined the last verified wild pigeon according to such historical records and determined that the last specimen was taken at Sargents, Pike County, Ohio on March 24, 1900. Greenberg uncovered records unknown to Schorger (detailed below) and decided that the last verified passenger pigeon in the wild was from Laurel, Franklin County, Indiana on April 3, 1902.

Amos Butler, prominent ornithologist, founder of the Indiana Audubon Society and author of Birds of Indiana (1898), obtained a record of passenger pigeons in the state in 1902. He reported in the Indiana Academy of Sciences that Mr. Chas K. Muchmore of Laurel, Indiana had obtained a specimen taken near Laurel April 3, 1902 that could be a passenger pigeon. Butler reported in the same journal in 1912 that the passenger pigeon was probably now extinct and declared that the last verified record of the bird in Indiana was the specimen shot by Muchmore of Laurel. Butler confirmed he had seen the specimen and found it to be a passenger pigeon. Muchmore wrote “The specimen taken was submitted to the writer for verification and was returned to Mr. C.K. Muchmore, the owner, at Laurel.” Letters at the Indiana Audubon Society from Charles K. Muchmore to Butler verify the story. Muchmore, which the 1900 US Federal Census shows as living in Laurel, Franklin County Indiana, working as a taxidermist, confirmed Butler’s story in the letters written in 1932. He wrote “Two specimens were seen April 3, 1902 by a Mr. Crowell, now living in Nebraska. He took one of them and brought it in to me for identification. I recognized it at once….My recollection is that I notified you of the specimen and later you drove to Laurel and identified it. I had it mounted myself, in the meantime. I know that you saw it here, personally.” Unfortunately, Muchmore reported that the specimen had been destroyed about seventeen years ago. Muchmore had moved and left his specimens behind with a friend. The friend’s wife put them in a woodshed attic and winter rains ruined the passenger pigeon specimen, and it had been thrown away. However, since Butler, an ornithologist had seen and verified the specimen, Greenberg counts this as the last verified passenger pigeon shot in the wild, even though the specimen has been destroyed.

Keywords

Science, Nature