Location: Shirley James Gateway Plaza, located at 298 S. 7th Ave., Evansville (Vanderburgh County), Indiana 47708.

Installed 2022 Indiana Historical Bureau, Mother Jones Heritage Project, Bil & Kim Musgrave, Labor Day Association, IBEW LU 16, Teamsters 215, USW 104, and Indiana PSO

ID#: 82.2022.1

Text

Side One

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones

Irish-born activist Mary “Mother” Jones organized workers across the U.S., demanding fair wages and safe working conditions. In Evansville, she rallied striking textile workers in 1901. She returned to Indiana often to speak on behalf of laborers and their families into the 1920s, including at the annual conventions of the United Mine Workers of America in Indianapolis.

Side Two

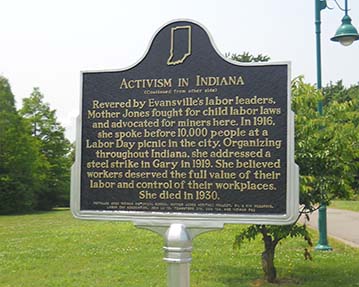

Activism in Indiana

Revered by Evansville’s labor leaders, Mother Jones fought for child labor laws and advocated for miners here. In 1916, she spoke before 10,000 people at a Labor Day picnic in the city. Organizing throughout Indiana, she addressed a steel strike in Gary in 1919. She believed workers deserved the full value of their labor and control of their workplaces. She died in 1930.

Annotated Text

Side One

Mary Harris "Mother" Jones

Irish-born activist Mary “Mother” Jones[1] organized workers across the U.S., demanding fair wages and safe working conditions.[2] In Evansville, she rallied striking textile workers in 1901.[3] She returned to Indiana often to speak on behalf of laborers and their families into the 1920s, including at the annual conventions of the United Mine Workers of America in Indianapolis.[4]

Side Two

Activism in Indiana

Revered by Evansville’s labor leaders, Mother Jones fought for child labor laws and advocated for miners here.[5] In 1916, she spoke before 10,000 people at a Labor Day picnic in the city.[6] Organizing throughout Indiana, she addressed a steel strike in Gary in 1919. She believed workers deserved the full value of their labor and control of their workplaces.[7] She died in 1930.[8]

[1] Mother Jones, The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005), 11-23; “Talk with Mother Jones,” Indianapolis News, January 25, 1901, 10, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones Fights Her First Foe; Yellow Fever,” Evansville Press, August 24, 1925, 4, Newspapers.com; “Reign of Terror in Chicago Witnessed by Mother Jones,” Evansville Press, August 25, 1925, 4, Newspapers.com; Elliott J. Gorn, Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 7-9, 22, 29, 34; Lois C. McLean, “Mother Jones,” West Virginia Encyclopedia, last updated January 14, 2021, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1053.

Details are Mother Jones’s birth and childhood are scant. “I was born in the city of Cork, Ireland, in 1830,” Mother Jones wrote in Autobiography, “My people were poor. For generations they had fought for Ireland 's freedom. Many of my folks have died in that struggle.” However, primary sources to verify this could not be found. Additionally, she said her birthday was May 1, which is International Workers’ Day, started in 1886 as a revolt of labor fighting for an eight-hour workday. It is possible that she chose this date as a symbolic gesture towards the working class, who she fought for her entire adult life.

Historian Elliott J. Gorn wrote in his authoritative biography, Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America, that she was likely born in 1837, as that is when she received her baptism, according to official church documents. As he wrote, “Richard and Ellen baptized their second-born child, Mary, at St. Mary's Cathedral in Cork on August 1, 1837.”

She and her family emigrated to Canada when she was a teenager. As she wrote in her Autobiography, “His [Richard Harris] work as a laborer with railway construction crews took him to Toronto, Canada. Here I was brought up but always as the child of an American citizen. Of that citizenship I have ever been proud.” The exact date of their departure to America is unclear, but as Gorn writes, “by the early 1850s, they had saved

enough for Ellen and the children to set sail for North America. The family was soon established in Toronto, with Richard Harris, approaching fifty, working on the rapidly growing Canadian railroads.”

She writes of her education and early vocations in her autobiography: “After finishing the common schools, I at

tended the Normal school with the intention of becoming a teacher. Dress-making too, I learned proficiently. My first position was teaching in a convent in Monroe, Michigan. Later, I came to Chicago and opened a dressmaking

establishment. I preferred sewing to bossing little children.” Biographer Elliott J. Gorn corroborates most of this, writing, “Mary learned the skills of dressmaking, but she was intent on another career. Late in 1857, at age twenty, she obtained a certificate from the priest at St. Michael's Cathedral attesting to her good moral character. With this credential, she took the examinations for admission to the Toronto Normal School, passed, and enrolled in November 1857. She never graduated, but she attended classes through the spring of 1858, getting more than enough training to secure a teaching position.”

She eventually made her way to Memphis, Tennessee, resuming her career as a teacher. It was here that she met and married her husband, George Jones, in 1861. She described him in her autobiography as “an iron moulder and a staunch member of the Iron Moulders' Union.” Gorn’s research confirms her description in her autobiography, writing, “Before the year [1860] was out, her wanderlust took her south to Memphis, Tennessee, where she began teaching again. Within a few short months, she met and married George Jones.”

Tragedy would forever reshape her life and work. In 1867, her husband and four children died in a yellow fever epidemic. She shared in perspective on this in an August 24, 1925 article for the Evansville Press, which was subsequently published in her autobiography:

In 1867, a yellow fever epidemic swept Memphis. Its victims were mainly among the poor and the workers. . . . One by one, my four little children sickened and died. I washed their little bodies and got them ready for burial. My husband caught the fever and died. I sat alone through nights of grief. No one came to me. No one could. Other homes were as stricken as was mine. All day long, all night long, I heard the grating of the wheels of the death cart.

After their deaths, she returned to Chicago and set up a clothing business, which was lost in the Great Fire of 1871. “The fire made thousands homeless,” Jones wrote in the Evansville Press, “We stayed all night and the next day without food on the lake front, often going into the lake to keep cool. Old St. Mary's church at Wabash Avenue and Peck Court was thrown open to the refugees and there I camped until I could find a place to go.”

All these events pushed her focus towards the cause of labor and the consequential role she would play in labor struggles for the rest of her life. “From the time of the Chicago fire,” she wrote in the Press, “I became more and more engrossed in the labor struggle[,] and I decided to take an active part in the efforts of the working people to better the conditions under which they worked and lived.”

[2] Mother Jones, The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005), 248-249; “Has Marched with the Strikers for Years,” Evansville Courier, November 5, 1897, 2, Newspapers.com; “The ‘Queen of the Mines’,” Monroeville Breeze, September 20, 1900, 6, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones . . .,” Indianapolis Journal, October 8, 1900, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Move on West Virginia,” Indianapolis News, November 29, 1900, 10, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Socialism’s Sun Shines,” Indianapolis News, February 23, 1901, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Socialism Advocated,” Indianapolis Journal, February 24, 1901, 7, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Servant Girls’ Union,” Indianapolis News, July 6, 1901, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Socialists are Lively,” Indianapolis Journal, July 30, 1901, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother’ Jones Talks of Future,” Evansville Journal, August 31, 1901, 3, Newspapers.com; “All Miners Know Her,” Indianapolis News, January 20, 1902, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Meeting of Socialists,” Indianapolis Journal, February 3, 1902, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Not So Large as Expected,” Indianapolis Journal, March 23, 1902, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother Jones’ Spoke,” Evansville Courier, March 24, 1902, 1, Newspapers.com; “To Show Power of Labor,” Indianapolis News, April 20, 1902, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones: Why the Miners Look Upon Her as the Noblest of all Women in the World,” Evansville Journal, July 19, 1902, 5, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Attacks Women of High Society,” Indianapolis News, March 26, 1903, 7, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Rotten to the Core,” Evansville Press, April 21, 1913, 1, Newspapers.com; “Society Women of New York All Parasites—Mother Jones,” Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram, February 4, 1915, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones Will Speak Here July 15,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, June 25, 1915, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “The ‘Queen of the Mines’”, “‘Mother’ Jones in Henderson Labor Day,” Evansville Courier, May 7, 1917, 5, Newspapers.com; “Will Hear ‘Mother’ Jones,” Terre Haute Daily Tribune, May 20, 1917, 7, Hoosier State Chronicles.

The above quote comes from an article in the Courier’s May 7, 1917 issue, in reference to her accepting an invitation to speech at the annual Labor Day event in Henderson, Kentucky, which is across the river from Evansville, Indiana. The full quote reads: “Local union men are in high glee over the fact that ‘Mother’ Jones [,] probably the most widely known woman labor leader in the United States, has accepted an invitation to make an address in this city on next Labor day.”

There are numerous other written attestations to her reputation within the labor movement. On one of her earliest visits to Evansville in 1897, the Evansville Courier did a write-up on said visit. “Mary Jones,” the Courier wrote, “better known to thousands of laboring men of the country as ‘Mother’ Jones, was in Evansville Thursday night. She is an exponent of social democracy and has devoted her life to the task of bettering the conditions of laboring men.”

In its September 20, 1900 issue, the Monroeville Breeze referred to Jones as the “Queen of the Mines” and “the Idol of the Miners.” The article elaborated: “This kind-hearted, philanthropic woman is so loved by the rough delvers of the coal mines in the anthracite regions that with them her word is law.”

The Indianapolis Journal printed on October 8, 1900, that “‘Mother Jones,’ of the anthracite coal district, seems to be more of a statesman and leader than Chairman Jones, of the Democratic national committee.” The Indianapolis News, writing about coal miners in West Virginia in 1900, stated Mother Jones had “more influence with the men and their families than any other person.”

Eugene V. Debs, Terre Haute native, labor activist and perennial Socialist Party candidate for President, wrote of Mother Jones in 1907, “She has won her way into the hearts of the nation's toilers and her name is revered at the altars of their humble firesides and will be lovingly remembered by their children and their children's children forever.”

The Terre Haute Tribune noted in its June 25, 1915, edition that “Mother Jones has a nation-wide reputation for her speeches in [sic] behalf of the miners.” Two years later, they published a short piece wherein they call her “the ‘guardian angel’ of the miners.”

[3] Mother Jones, The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005), 114-132, 267-268; “Miners Conclude Work,” Indianapolis Journal, January 31, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones, with Child Army, Moving on to New York City,” Indianapolis News, July 15, 1903, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Roosevelt Will Not Receive Them,” Evansville Courier, July 17, 1903, 2, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Marched,” Indianapolis Journal, July 24, 1903, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “One of Labor’s Women Agitators,” Indianapolis Journal, July 26, 1903, 28, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Child Army Led by Mother Jones,” Indianapolis Times, August 26, 1925, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “East is Stirred by ‘Army’ of Children,” Evansville Press, August 28, 1925, 10, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Toils with Children of Cotton Mills,” Evansville Press, September 1, 1925, 5, Newspapers.com.

In her Autobiography, she described the conditions that children working in a textile mill experienced in Cottondale, Alabama:

Little girls and boys, barefooted, walked up and down between the endless rows of spindles, reaching thin little hands into the machinery to repair snapped threads. They crawled under machinery to oil it. They replaced spindles all day long, all day long; night through, night through. Tiny babies of six years old with faces of sixty did an eight-hour shift for ten cents a day. If they fell asleep, cold water was dashed in their faces, and the voice of the manager yelled above the ceaseless racket and whir of the machines.

These experiences, among many others, motivated Mother Jones to help both child and adult textile workers organize around the country. In 1901, after the annual meeting of the United Mine Workers of America in Indianapolis, she traveled to Evansville “where the women textile workers are on strike. She will do what she can to adjust matters,” wrote the Indianapolis Journal. The strike was settled on January 31, 1902; the Louis H. Meier & Company “agreed to pay the union scale and reinstate all the strikers,” the Journal reported. It also noted that “‘Mother’ Jones, an organizer for the United Mine Workers, assisted in bring about a settlement.”

In 1903, she led a march of textile workers to confront President Theodore Roosevelt on the conditions they suffered in the industry. As the Indianapolis Journal reported on July 26, 1903, Mother Jones “has not blossomed forth as the leader of a wonderful pilgrimage. At the head of a band of men and boys from the textile mills she marched on foot from Philadelphia to New York in an endeavor to stir up popular sympathy in favor of a shorter workday for the mill workers.”

In one her speeches during the march, as printed by the Indianapolis News, she declared, “I have seen some children killed by slow starvation and others maimed and torn . . . . What is to become of the next generation when this generation is being torn from the cradles to thrown into the factories.”

While President Roosevelt did not receive her or the textile workers, their efforts did culminate in the passage of a child labor law in Pennsylvania. The bill’s enactment, as Mother Jones wrote in the Evansville Press, “sent thousands of children home from the mills, and kept thousands of other from entering the factory until they were fourteen years of age.”

[4] Mother Jones, The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005), 3, 228-229; Mother Jones, Speeches and Writings of Mother Jones, Edward M. Steel, ed. (Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg Press, 1988), 3-14, 254-259; Mother Jones, Mother Jones Speaks: Collected Speeches and Writings, Philip Foner, ed. (New York: Monad Press, 1983), 77, 83-90, 120-135, 138-139, 329, 462-464, 489-490, 528-530; “Mine Workers are Here,” Indianapolis Journal, January 21, 1901, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Miners Convened,” Indianapolis News, January 21, 1901, 1-2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother Jones’ Here,” Indianapolis Journal, January 24, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones to Speak,” Indianapolis News, January 24, 1901, 10, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Labor Speeches Made,” Indianapolis Journal, January 25, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Action of the Miners,” Indianapolis Journal, January 26, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Working on the Scale,” Indianapolis News, January 26, 1901, 13, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Popular with Miners,” Indianapolis Journal, January 29, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Anthracite Miners Win,” Indianapolis News, January 29, 1901, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Miners Conclude Work,” Indianapolis Journal, January 31, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “To Mine Workers,” Indianapolis News, December 23, 1901, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “All Miners Know Her,” Indianapolis News, January 20, 1902, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones Talked,” Indianapolis News, January 21, 1902, 11, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Down to Business,” Muncie Times, January 21, 1902, 3, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Indignant,” Indianapolis News, January 22, 1902, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother’ Jones’s Address,” Indianapolis Journal, January 27, 1902, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Tampering with Miners’ Mail,” Indianapolis News, January 27, 1902, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones is Against Big Strike,” Evansville Journal, July 19, 1902, 1, Newspapers.com; “Action of Convention,” Indianapolis Journal, July 20, 1902, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Bitter Struggle Among Leaders Comes to End,” Evansville Press, January 20, 1916, 1, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Ends Squabble,” Indianapolis News, January 20, 1916, 1, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones Quiets Her Fussing Boys in a Speech that Stampedes Miners Toward Burial of Hatchet,” Princeton Daily Clarion, January 20, 1916, 1, Newspapers.com; “Fight Over Mine Wage Agreement,” Indianapolis News, January 18, 1918, 1, 20, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Still with Miners,” Indianapolis Times, September 27, 1921, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Would be Aid to Both,” Evansville Press, October 4, 1921, 1, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Quells Disorder in Union Miners’ Convention,” Evansville Journal, February 18, 1922, 1, 2, Newspapers.com.

Mother Jones’s appearances at the UMWA conventions often served two purposes—as a morale boost or as a conflict resolver. For example, at her first convention in 1901, Mother Jones directly encouraged the growth of organizing, especially among women:

My friends, I am not the only woman who is going to take up the battle of the miners. We propose to organize every mining camp in this country, we propose to get our women together and keep them together. We were with you in your battles, we were with you in your darkest hour, we were with you in your prosperity, and I believe we should be with you in your organization.

The Indianapolis Journal noted of her speech that, “Her pointed and witty expressions caused many outbursts of laughter and her ability to appeal to the deeper feelings was equally as effective with the delegates.”

Her final appearance at the UWMA convention in 1922 served as an example of her ability resolve conflicts. As the leaders and delegates of the convention were torn on the issue of whether to call for a strike, the level of cantankerousness rose. As she wrote in her Autobiography, “Everyone was howling and bellowing and jumping on his feet and yelling to speak. They sounded like a lot of lunatics instead of sane men with the destiny of thousands of workers in their hands.” She rose to speak and encouraged them to settle the issue calmly by vote:

Some one called “Speech !”

“This is not the time for me to speak,” I said. “It is time for you to act. Trust your president. If he fails we can go out and I will be with you and raise Hell all over the nation!”

After that the Convention got down to business and voted to leave the matter of striking to those who had to do the sacrificing: the rank and file.

The Evansville Journal echoed her own recollections, writing, “The roll call, that had ceased during the noise, could not be resumed and then Mother Jones made her dramatic appearance. The howls and hoots changed almost instantly to cheers and she began addressing the delegates.”

[5] Mother Jones, The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005), 2, 30, 258-262; “Crushed to Death,” Evansville Courier, June 8, 1888, 4, Newspapers.com; “A Coal Miner Injured,” Evansville Courier, March 11, 1897, 8, Newspapers.com; “By a Premature Blast,” Evansville Journal, March 11, 1897, 8, Newspapers.com; “Burned by Gas Explosion,” Evansville Courier, April 14, 1898, 6, Newspapers.com; “Miners Demand the Old Scale,” Evansville Courier, August 13, 1898, 5, Newspapers.com; “Down in the Coal Mines,” Indianapolis Journal, January 29, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones Here,” Indianapolis News, June 13, 1901, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother’ Jones in the City,” Indianapolis Journal, June 14, 1901, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother’ Jones Here,” Indianapolis Journal,August 30, 1901, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “A Coal Miners’ Meeting,” Indianapolis Journal, October 30, 1901, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother’ Jones in Town,” Indianapolis Journal, January 19, 1902, 10, Hoosier State Chronicles; “The Great Banquet,” Indianapolis Journal, January 31, 1902, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “The Strike Settled,” Indianapolis Journal, January 31, 1902, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones in the City,” Indianapolis News, June 28, 1902, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “ ‘Mother’ Jones to be in City To-day,” Evansville Journal, June 29, 1902, 16, Newspapers.com; “‘Mother Jones’ Predicts That Coal Strike Will Be General,” Evansville Courier, June 30, 1902, 1, Newspapers.com; “‘Mother’ Jones Spoke,” Indianapolis Journal, June 30, 1902, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones is Against Big Strike,” Evansville Journal, July 19, 1902, 1, Newspapers.com; “‘Mother Jones’ the Labor Agitator,” Evansville Courier, July 20, 1902, 20, Newspapers.com; “Miners Declared Guilty,” Indianapolis News, July 24, 1902, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Wilson is Wanted,” Indianapolis Journal, July 25, 1902, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “No Arrest of the Miner’s Secretary,” Indianapolis News, July 25, 1902, 11, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Remarks of ‘Mother Jones,’” Plymouth Tribune, July 31, 1902, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones, the picturesque figure. . .,” Muncie Evening Press, August 22, 1902, 3, Newspapers.com; “‘Mother’ Jones Arrives,” Indianapolis Journal, September 25, 1902, 7, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Misery is Depicted in Eastern Coal Region,” Evansville Journal, September 28, 1902, 3, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones in Town,” Indianapolis News, December 13, 1902, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Miner Dies from Burns,” Richmond Palladium, November 9, 1921, 6, Newspapers.com.

Injuries and deaths of coal miners in Evansville over decades were chronicled in the papers of its local newspapers. Frank Hudson, a 19-year-old miner who worked at the Diamond Coal Company’s mines in Evansville, was “crushed to death” by “a heavy piece of soapstone” near a worksite entrance in 1888, as reported by the Evansville Courier. In 1897, another miner named William Delgeman was nearly killed at the Diamond coal mine by a likely premature blast explosion, leaving him with a broken arm and severe burns, the locals Courier and Journal noted. The Courier reported a massive explosion in 1898 “hurled backward” worker Daniel Breidenbach and “burned both arms from the elbows to the tips of his fingers and also burned his face and the back of his neck.” In 1902 the Journal reported that when Mother Jones was attending the annual UMWA convention in Indianapolis, one coal worker, William Cox, died of injuries sustained when slate fell on him. Three other workers were injured in similar circumstances. Over 20 years later, on November 9, 1921, miner Ben Harper died in the hospital after severe burns from an explosion, as noted by the Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram.

Due to these horrific circumstances, workers began to organize, and the United Mine Workers of America was founded in 1890. Mother Jones described this organizing work in her Autobiography: “The United Mine Workers decided to organize these fields and work for human conditions for human beings. Organizers were put to work. Whenever the spirit of the men in the mines grew strong enough a strike was called.”

Her title as “organizer” for the UMWA is confirmed by many newspaper articles. As examples, she was reappointed as an organizer in 1901 at the UMWA annual convention, the Indianapolis Journal wrote, and the Indianapolis News referred to her as “an official organizer of the United Mine Workers” on August 30, 1901. The Indianapolis Journal referred to Jones as “the most successful organizer in the United Mine Workers’ organization” when she was in town for the UMWA convention in 1902.

On June 29, 1902, Mother Jones gave a speech to 2,000 miners in Evansville, who subsequently called for a general strike. In excerpts from her speech in the Evansville Courier, she elaborated on the causes of the strike and possible solutions. “As long as conditions are allowed to remain as they are in this country, there will be continued strike between labor and capital. The only real solution is for governmental control. That can only be accomplished at the ballot box.” While she initially supported a general strike, by July of 1902, she agreed with the delegates at the national UMWA convention in Indianapolis that “to avoid such a movement was the wisest course,” the Evansville Journal reported.

[6] Mother Jones, The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005), 3, 163-167, 275, 278; Mother Jones, Mother Jones Speaks: Collected Speeches and Writings, Philip Foner, ed. (New York: Monad Press, 1983), 612-613; Speeches and Writings of Mother Jones, Edward M. Steel, ed. (Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg Press, 1988), 276; “Stone Throwing May Kill Kern’s Peonage Inquiry,” Indianapolis Star, May 10, 1913, 1-2, Newspapers.com;“West Virginia as Seen by Non-Socialists,” Indiana Socialist, May 24, 1913, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Broad Investigation Ordered by Senate,” Indianapolis News, May 28, 1913, 3, Newspapers.com; “The Paper that Does Things,” Appeal to Reason, November 1, 1913, 1, Newspapers.com; “Want ‘Mother’ Jones for Labor Day Talk,” Evansville Journal, May 14, 1916, 11, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones is Coming,” Evansville Press, May 29, 1916, 1, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Coming,” Evansville Courier, July 9, 1916, 13, Newspapers.com; “White Horses to Haul Bosse and Mother Jones,” Evansville Journal, August 27, 1916, 1, Newspapers.com; “Evansville…,” Indianapolis News, August 28, 1916, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Labor Day Parade and Line of March,” Evansville Courier, September 1, 1916, 3, Newspapers.com; “Hale as a Girl at Age of 86,” Evansville Courier, September 4, 1916, 1, Newspapers.com; “‘Mother’ in Search of Quiet,” Evansville Journal, September 4, 1916, 1, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Demands 6-Hour Day; Wants Wilson,” Evansville Press, September 4, 1916, 1, Newspapers.com; “Celebrations Elsewhere in Indiana,” Indianapolis News, September 4, 1916, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Wilson and Kern Labor’s Friends,” Evansville Courier, September 5, 1916, 1, 4, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Makes Speech,” Indianapolis News, September 27, 1916, 22, Hoosier State Chronicles; “‘Mother Jones’ Proud of the Local Labor Day,” Evansville Courier, October 7, 1916, 11, Newspapers.com; “Official Labor Day Celebration,” Evansville Press, August 29, 1917, 2, Newspapers.com; “Boats Take Local Crowd to Hear ‘Mother’ Jones,” Evansville Press, September 1, 1917, 4, Newspapers.com; “Parade Features Celebration at Henderson,” Evansville Journal, September 4, 1917, 2, Newspapers.com; Elliott J. Gorn, Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 238.

Senator John W. Kern of Indiana intervened on Mother Jones’s behalf when she was imprisoned in West Virginia during a strike action while organizing in 1912. As the Indiana Socialist reported on May 24, 1913, “the climax of this new form of government came the dastardly arrest of ‘Mother’ Jones on the charge of murder. The mockery of it was sickening. She has fought the good fight against the murder of little children in the mines of enlightened States [sic].” Learning of the condition that she and others imprisoned experienced, Senator Kern opened an inquiry into said conditions and read a telegram from Mother Jones on the Senate floor. Jones recounted this telegram in her Autobiography:

From out the military prison walls of Pratt, West Virginia, where I have walked over my eighty-fourth milestone in history, I send you the groans and tears and heartaches of men, women and children as I have heard them in this state. From out these prison walls, I plead with you for the honor of the nation, to push that investigation, and the children yet unborn will rise and call you blessed.

On May 27, 1913, the Senate adopted Kern’s resolution and a “broad investigation” was opened in the Senate on the conditions of the coal mines in West Virginia, the Indianapolis News reported. Three days earlier, on May 24, Mother Jones was released from jail, according to the Appeal to Reason.

Three years after the events in West Virginia, at her speech at the UMWA convention on January 20, 1916, she applauded Kern for his efforts to help her get out of jail. “I presume I would still be in jail in West Virginia if Senator Kern had not taken the matter up,” she declared to the delegates, “I want to say to you that every working man in the nation owes a debt to Senator Kern.”

As historian Elliott J. Gorn wrote of her 1916 speech in Evansville, “At the annual Labor Day picnic in Evansville, Indiana, for example, she declared her socialist beliefs but endorsed Woodrow Wilson for reelection, saying, "Socialism is a long way off; I want something right now!’” In her calls for a 6-hour workday, Mother Jones said, “With modern machinery all the work of the world could be done in six hours a day. . . . The worker would have time to improve his mind and body.” Regarding Kern and his efforts to get her out of jail in 1913, Jones said “the miners owe Senator Kern a debt which they can never repay.” He lost his reelection in 1916 and died shortly after his loss on August 17, 1917.

Reflecting years later in her Autobiography, Mother Jones said of Kern (who she mistakenly refers to as “Kearns”):

The working men had much to thank Senator Kearns [sic] for. He was a great man, standing for justice and the square deal. Yet, to the shame of the workers of Indiana, when he came up for re-election [sic] they elected a man named Watson, a deadly foe of progress. [The man who defeated Kern was Republican Harry New, not a man named Watson.] I felt his defeat keenly, felt the ingratitude of the workers. It was through his influence that prison doors had opened, that unspeakable conditions were brought to light. I have felt that the disappointment of his defeat brought on his illness and ended the brave, heroic life of one of labor's few friends.

[7] Mother Jones, The Autobiography of Mother Jones (Chicago: Charles H. Kerr Publishing Company, 2005), 209-226; Mother Jones, Mother Jones Speaks: Collected Speeches and Writings, Philip Foner, ed. (New York: Monad Press, 1983), 316-319; 477-480; “South Bend. . .,” Indianapolis Star, January 9, 1915, 5, Newspapers.com; Mother Jones, “‘Mother’ Jones to Tell John D. Jr., Trend of Times,” Evansville Press, January 28, 1915, 1, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Says She is Bolshevik,” Evansville Journal-News, October 24, 1919, 2, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones, at 90, Joins Battle of Steel Strikers,” Evansville Press, September 9, 1925, 7, Newspapers.com.

The steel workers strike of 1919 centered around worker’s rights and protections, which had been hampered by armament efforts during World War I. Writing in her Autobiography, Mother Jones notes:

So believing, the steel workers, 300,000 of them, rose en masse against Kaiser Gary, the President of the American Steel Corporation. The slaves asked their czar for the abolition of the twelve-hour day, for a crumb from the huge loaf of profits made in the great war, and for the right to organize.

As such, she joined other organizers and made her way across the country, advocating for steel workers. In one instance, she was arrested for her efforts, which angered many protesters. As she recalled in the Evansville Press, “we were taken to jail. A great mob of people collected outside the prison. There was angry talk. The jailer got scared. He came to me and asked me to speak to the boys outside and ask them to go home. I got them in a good human and pretty soon they went away.” She was arrested “frequently” during the strike, according to her recollections in the Press.

In her speech in Gary, Indiana on October 24, 1919, she called for the nationalization of the steel mills, with the intention of turning them into worker cooperatives. As she said, “we’re going to change the name and we’re going to take over the steel works and we’re going to run them for Uncle Sam. It’s the damned gang of robbers and their political thieves that will start the American revolution and it won’t stop until every last one of them is gone.” She also allied herself with the emerging Bolshevik revolutionaries in Russia. “If Bolshevist is what I understand it to be,” she declared, “then I’m a Bolshevist from the bottom of my feet to the top of my head. All the world’s history never produced a more brutal and savage time than this and Mr. Soldier, I’m ready to prove my statement that we’ve got to change or this nation will perish. This is the century of the worker.”

She had called for establishing worker cooperatives before. She came to South Bend, Indiana on January 9, 1915, where she was “urging labor men to open co-operative department stores” in cities across northern Indiana and southern Michigan, according to the Indianapolis Star. She was also an advocate for revolution. In an editorial published in the Evansville Press on January 28, 1915, she called for revolution in a blistering editorial directed as industrialist John D. Rockefeller, Jr. “There is a time for law and a time for revolution,” she wrote, “Abraham Lincoln entered the white house a radical, but he became a revolutionist when he emancipated the slaves.”

[8] Mother Jones, Mother Jones Speaks: Collected Speeches and Writings, Philip Foner, ed. (New York: Monad Press, 1983), 695; Mother Jones, Correspondence of Mother Jones, Edward M. Steel, ed. (Pittsburg: University of Pittsburg Press, 1985), 344-345; “Mother Jones is Now 96; Fighting Days are Over,” Evansville Press, August 22, 1925, 1, Newspapers.com; “Peace Dawns for Labor as Mother Jones’ Years Fade,” Evansville Press, September 10, 1925, 14, Newspapers.com; Herbert Plummer, “‘Mother Jones’ Nearing Century Mark; Very Ill,” Evansville Journal, April 2, 1930, 6, Newspapers.com; Sue McNamara, “‘Mother’ Jones, Near Century Mark, is Still Militant for Labor Cause,” Evansville Journal, April 27, 1930, 31, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Gets Century Cake,” Evansville Press, May 6, 1930, 3, Newspapers.com; Lawrence Sullivan, “Mother Jones Joins Rebel Miner Ranks,” Evansville Press, September 6, 1930, 1, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones Destroys Will,” Muncie Post-Democrat, September 12, 1930, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; Ronald Van Tine, “Mother Jones Awaits Death,” Muncie Evening Press, September 13, 1930, 1, Newspapers.com; “Fighter for a Century, ‘Mother’ Jones Battles Again as Death Nears,” Evansville Journal, September 25, 1930, 1, 10, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones is Near Death,” Indianapolis Times, October 2, 1930, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones Safe,” Indianapolis Times, October 21, 1930, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Labor Today Owes Many Rights To Mother Jones’ Lifelong Fight,” Evansville Press, December 1, 1930, 8, Newspapers.com; “‘Mother’ Jones, Labor Crusader, Succumbs at 100,” Indianapolis Star, December 1, 1930, 1-2, Newspapers.com; “Mother Jones, Century-Old Labor Crusader, Is Dead,” Indianapolis Times, December 1, 1930, 1, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mother Jones ‘Home’; Burial to be Monday,” Indianapolis Times, December 5, 1930, 10, Hoosier State Chronicles; Elliott J. Gorn, Mother Jones: The Most Dangerous Woman in America (New York: Hill and Wang, 2001), 7-9; Lois C. McLean, “Mother Jones,” West Virginia Encyclopedia, last updated January 14, 2021, accessed May 9, 2022, https://www.wvencyclopedia.org/articles/1053.

By 1925, Mother Jones’s days of traveling the country on behalf of workers came to end, largely as a result of her advancing age and health issues, specifically rheumatism, the Evansville Press reported. She blamed her imprisonment in Walsenburg, Colorado in 1913 for the disease, saying, “it was a cold, dark, dank hole unfit for a dog to live in.” She did not take her retirement from organizing lightly. “I hate to be idle,” she said to the Press, “when there is so much work to be done.” Weeks later, on September 10, 1925, she wrote in the Press, “the last years of my life have seen fewer and fewer strikes. Both employer and employe [sic] have become wiser.”

In 1928, she picked where she wanted to be buried— Mt. Olive, Illinois, the site of brutal strike breakings from 1898-1907 that left 14 miners killed. She wrote to the local miners there on November 12, 1928, asking that “I get a resting place in the same clay that shelters the miners who gave up their lives on the hills of Virden, Illinois, on the morning of October 12, 1907.”

Newspaper articles routinely cited her condition as “near death” in 1929 and 1930, including the Franklin Evening Star, Muncie Evening Press, Indianapolis Times, and the Evansville Journal. She celebrated her “100th birthday” on May 1, 1930, with a big, 100-candle cake, “hundreds of telegrams from labor unions all across the country, and masses of floral tributes,” according to the Evansville Press.

Her last major action on behalf of workers was joining the fight against the nomination of John L. Lewis to lead the United Mine Workers. The September 6, 1930 issue of the Evansville Press reported that she “decided to throw her meager life’s savings into the fight against John L. Lewis; domination of the United Mine Workers of America.” She loathed Lewis, writing in a letter to John H. Walker that “that fellow Lewis was a crook the day he was born.” Walker lead the Reorganized United Mine Workers of America (RUMWA), a rival faction of mine workers who took on Lewis. Mother Jones gave Walker and the RUMWA $1,000 in the fight against Lewis. On September 25, 1930, she said to the Evansville Journal, “I only hope I may live long enough to see John L. Lewis licked.” She saw Lewis as more interested in his own success than the success of the miners. Unfortunately for Mother Jones, Lewis won the fight and continued to lead the UMWA until 1960.

On November 30, 1930, Mary “Mother” Jones died at the age of either 92 or 93 (claimed as 100) at her home in Silver Springs, Maryland. Numerous obituaries are tributes were published in Indiana newspapers. William Green, the head of the American Federation of Labor, said in the Indianapolis Times, “in the death of Mother Jones a unique and picturesque figure has been removed from the ranks of labor . . . . The loss sustained can not be measured and the services rendered will never be surpassed or excelled.” As Bruce Catton wrote for the Evansville Press, “the workingman these days get a far better break than he did when Mother Jones first entered the arena; and a part of this improvement, at least, is due to Mother Jones herself.”

In her will, she left $10,000, her entire life savings, “to the cause of labor,” the Times wrote. Specifically, she testified in her will: “I hereby devise and bequeath all cash in the First National Bank of Hyattsville, Md., Bonds, Real, Personal and mixed property, which I now have and which I may hereafter acquire to, Edward N. Nockels and John Fitzpatrick, of Chicago, as Trustees, to dispose of as they deem best, after my death.” Fitzpatick and Nockels were known labor leaders and trusted confidants of Mother Jones.

As she requested in 1928, Mother Jones was buried at the United Miners Cemetery in Mt. Olive, Illinois, next to miners who gave their lives to the cause of labor. The Indianapolis Times described her funeral train’s procession into Mt. Olive: “A crowd of almost five thousand persons, many of them miners, stood silently Thursday night as the body of Mother Jones was taken from a train which had brought it from Washington. . . . All along the route from the east homage was paid at every stop to the memory of Mother Jones. Miners in many towns placed wreaths upon her coffin.”

Keywords

Business, Industry, & Labor