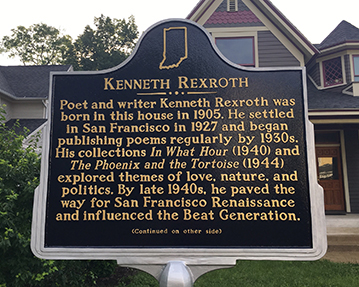

Location: 828 Park Avenue in South Bend (St. Joseph County, Indiana), 46616

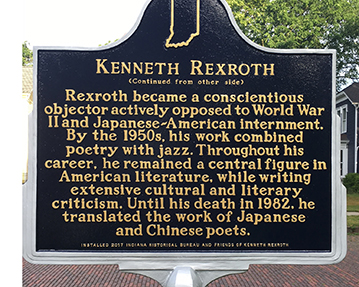

Installed 2017 Indiana Historical Bureau and Friends of Kenneth Rexroth

ID#: 71.2017.1

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog or

Visit the Indiana History Blog or  listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more aboutto learn more about Rexroth's life and work.

listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more aboutto learn more about Rexroth's life and work.

Text

Side One

Poet and writer Kenneth Rexroth was born in this house in 1905. He settled in San Francisco in 1927 and began publishing poems regularly by 1930s. His collections In What Hour (1940) and The Phoenix and the Tortoise (1944) explored themes of love, nature, and politics. By late 1940s, he paved the way for San Francisco Renaissance and influenced the Beat Generation.

Side Two

Rexroth became a conscientious objector actively opposed to World War II and Japanese-American internment. By the 1950s, his work combined poetry with jazz. Throughout his career, he remained a central figure in American literature, while writing extensive cultural and literary criticism. Until his death in 1982, he translated the work of Japanese and Chinese poets.

Annotated Text

Side One:

Poet and writer Kenneth Rexroth was born in house here in 1905.[1] He settled in San Francisco in 1927[2] and began publishing poems regularly by 1930s.[3] His collections In What Hour (1940) and The Phoenix and the Tortoise (1944) explored themes of love, nature, and politics. [4] By late 1940s, he paved the way for San Francisco Renaissance[5] and influenced the Beat Generation.[6]

Side Two:

Rexroth became a conscientious objector actively opposed to World War II[7] and Japanese-American internment.[8] By the 1950s, his work combined poetry with jazz.[9] Throughout his career, he remained a central figure in American literature,[10] while writing extensive cultural and literary criticism.[11] Until his death in 1982,[12] he translated the work of Japanese and Chinese poets.[13]

Note: There are two Kenneth Rexroth autobiographies used here that share a title but contain different content. The first, published in 1966, covers only his early life, ending upon his arrival in San Francisco in 1927: Kenneth Rexroth, An Autobiographical Novel (Garden City, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1966). The second version, published in 1991, expands the story to 1949: Kenneth Rexroth, An Autobiographical Novel (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1991). According to the scholar and translator Ken Knabb, this second volume includes a “Postlude” that Rexroth wrote for a 1978 reprint of the first edition, later chapters from a small volume called Excerpts from a Life published 1981, and previously unpublished material assembled by his biographer Linda Hamalian. The versions will be distinguished in the short cites by using Volume I or II and then the page number.

Several articles and poems by Rexroth were accessed through the website with the seemingly strange title “Bureau of Public Secrets.” While not hosted by a scholarly institution or university, the site’s content has been compiled by the writer and scholar Kenneth Knabb, author of The Relevance of Rexroth (1990), and checked against other sources and editions when possible.

[1] Directory of South Bend, Mishawaka and Rural Route Lists of St. Joseph County, Indiana (South Bend: The Tribune Printing Company, 1905), 65, 311, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Directory of South Bend, Mishawaka and Rural Route Lists of St. Joseph County, Indiana (South Bend: The Tribune Printing Company, 1906), 124, 529, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Moving to Elkhart,” Elkhart Daily Review, June 29, 1908, 1, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; 1910 United States Census, District 13, Elkhart County, Indiana, Roll T624_347, page 4B, Line 87, April 18, 1910, accessed AncestryLibrary.com;

Kenneth Rexroth was born on December 22, 1905 in a house at 828 Park Avenue in South Bend, Indiana. The Rexroth family also lived in Elkhart, Indiana, by 1908.

[2] R. L. Polk & Co.’s San Francisco Directory (San Francisco: R. L. Polk & Co., 1929), 1263, U. S. City Directories, 1822-1996, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Rexroth I: 367; Rexroth, II: 369-371.

Rexroth wrote in the first edition of his autobiography that he arrived in San Francisco in the summer of 1927; He recalled in his autobiography that Sacco and Vanzetti were executed in his third week in San Francisco (which occurred August 22, 1927).

[3] Kenneth Rexroth, “At Lake Desolation,” The New Republic 82, Issue 1056 (May 1, 1935) 336, accessed EbscoHost.com; “First National Anthology,” Oxnard (California) Daily Courier, June 7, 1937, 2, accessed NewspaperArchive.com; “Art Born ‘On the Town,’” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, August 29, 1937, 60, accessed Newspapers.com; “New Books Passed in Review,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, September 7, 1938, 6, accessed Newspapers.com; James Laughlin, ed., New Directions in Prose and Poetry (New York: New Directions Publishing, 1937); Kenneth Rexroth, “Poetry and Society,” The Coast: A Magazine of Western Writing (Federal Writers’ Project of the Federal Works Progress Administration of Northern California, 1937), 33; Rexroth, II: 375-77.

Starting in the 1930s, during the Great Depression, Rexroth was employed by the Work’s Progress Administration (WPA). He was writing poetry and publishing work in journals and small volumes of poetry. His poem “At Lake Desolation” was published in the magazine The New Republic in 1935. Some of Rexroth’s poems were published in volumes of work by WPA writers, American Stuff in 1937 and Poetry in 1938. Rexroth wrote that he was also an editor for the WPA Writer’s Project. The influential editor James Laughlin included Rexroth’s work in the 1937 edition of the annual collection New Directions in Prose and Poetry.

[4] Kenneth Rexroth, In What Hour (New York: The Macmillan Company, 1940); Kenneth Rexroth, The Phoenix and the Tortoise (New York: New Directions Press, 1944); Rexroth, II: 375-7; “’Poet In New Manner’ Puzzles and Pleases,” Oakland (California) Tribune, September 1, 1940, 18, accessed Newspapers.com; Hamalain, 58; American Academy of Poets, “Kenneth Rexroth,” accessed Poets.org; Morgan Gibson quoted in “Kenneth Rexroth,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/kenneth-rexroth; John Palattella, “’The Heart’s Garden:’ The Day that Kenneth Rexroth Died Was Not A Dark, Cold Day,” The Nation, October 31, 2002, accessed www.thenation.com/article/hearts-garden.

After moving to San Francisco, Rexroth was inspired by his natural surroundings. Describing the beauty of the natural landscape, he wrote in his autobiography, “My poetry and philosophy of life became what it’s now fashionable to call ecological. I came to think of myself as a microcosm in a macrocosm, related to chipmunks and bears and pine trees and stars and nebulae and rocks and fossils, as part of an infinitely interrelated complex of being. This I have retained.”

Rexroth biographer Linda Hamalain wrote that in the poems that make up In What Hour “demonstrate his remarkable ability to render plausible the possibility of spiritual presence and a sense of unity in the natural world” despite the threats of the modern age. According to the Academy of American Poets, “Rexroth’s first collection, In What Hour . . . articulated the poet’s ecological sensitivities along with his political convictions.” According to a writer for The Nation, a magazine which Rexroth had contributed to over his career, “In What Hour is the first sustained exploration of the two subjects that dominate Rexroth’s work: politics and nature.”

He further explored the idea that love and nature could serve as spiritual refuge in troubled political times in The Phoenix and the Tortoise. According to Rexroth scholar Morgan Gibson, in this 1944 work, Rexroth wrote from the viewpoint of "the 'integral person' who, through love, discovers his responsibility for all in a world of war, cold war, and nuclear terror." According to Michael Davidson in his monograph on the San Francisco Renaissance, The Phoenix and the Tortoise, was a “meditation on history . . . given focus by reference to an as yet untouched (but threatened) landscape.” According to Nation literary editor John Palattella, Rexroth views the nature as “a sanctuary, a realm of mutability that absorbs and transforms the mutilated world of war.” For more on the themes of The Phoenix and the Tortoise, see footnote 7.

[5] Kenneth Rexroth, “Les Lauriers Sont Coupés,” Circle 3, 1944; Circle 4, 1944; Circle 6, 1945, Verdant Press, accessed verdantpress.com/checklist/circle-magazine; “Noted Poet to Lecture at U.,” Salt Lake Tribune, November 19, 1948, 31, accessed Newspapers.com; Kenneth Rexroth, “The San Francisco Renaissance,” San Francisco Magazine, February 1975, accessed Bureau of Public Secrets; Kenneth Rexroth, “End of a Golden Age,” San Francisco Magazine, July 1975, accessed Bureau of Public Secrets; John Tytell, Naked Angels: The Lives and Literature of the Beat Generation (New York: Grove Press, Inc., 1976), 103-4; Kenneth Rexroth, Excerpts from a Life, ed. Brad Morrow (Santa Barbara California: A Conjunctions Book, 1981), 58; Ann Charters, ed., The Portable Beat Reader (New York: Penguin Books, 1992), 227-9.

Since World War II, a small group of avant garde writers which included Rexroth flourished in San Francisco. Several of these rebellious writers who were exploring anti-establishment and far left politics in their literature along with other cultural critiques were published in the magazine Circle. Rexroth also maintained what Beat scholar John Tytell called “a sort of western salon, a weekly literary gathering,” where Rexroth introduced poets to each other and hosted readings. One newspaper described it in 1948 as “the San Francisco bay area poetry forum.”

Rexroth himself considered the combination of political discussion, poetry, and jazz to be the foundation of the movement. He wrote in an autobiography:

We had the largest meetings of any radical or pseudo-radical group in San Francisco. The place was always crowded and when the topic was sex and anarchy you couldn’t get in the doors. . . In addition to meetings of the Libertarian Circle [an anarchist group Rexroth founded], we had weekly poetry readings. At the dances we always had the best local jazz groups . . . This was the foundation of the San Francisco Renaissance and of the specifically San Francisco intellectual climate…”

Rexroth recalled the movement in a series of columns written in 1975 San Francisco Magazine. He wrote:

Just as London under the buzz bombs enjoyed a literary renaissance and a profound change of social relationships . . . so San Francisco during the War woke up from a long provincial sleep and became culturally a world capital. The reasons were somewhat the same.

These reasons, according to Rexroth, included the arrival of exiles from other places dedicated to pacifism, many of whom were poets and artists, or “highly civilized people pouring into the City.” Out of this meeting of minds came “an entirely new cultural synthesis” which produced new movements in theater, art, and poetry. He concluded his final column on the San Francisco Renaissance thusly: “It was a Golden Age and great fun to have lived through…”

[6] W. G. Rogers, “The Literary Guidepost: New Poetry Anthology Rounds-Up Trends of Present Day Writing,” Denton (Texas) Record-Chronicle, January 5, 1951, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; Kenneth Rexroth, “San Francisco’s Mature Bohemians,” The Nation 184: 8 (February 1957), 159-62, accessed EbscoHost.com; Webster Schott, “Writers Dig the Beat Generation,” Kansas City (Missouri) Times, February 27, 1958, 34, accessed Newspapers.com; Kenneth Rexroth, “The San Francisco Renaissance,” San Francisco Magazine, February 1975, accessed Bureau of Public Secrets; Kenneth Rexroth, “The Beat Era,” San Francisco Magazine, April 1975, accessed Bureau of Public Secrets; Kenneth Rexroth, “Haight-Ashbury and the Sixties,” San Francisco Magazine, May 1975, accessed Bureau of Public Secrets; Charters, 227-232; “A Brief Guide to the Beat Poets,” Academy of American Poets, accessed Poets.org.

According to the Academy of American Poets, “Beat poetry evolved during the 1940s in both New York City and on the west coast, although San Francisco became the heart of the movement in the early 1950s.” The Beat Generation rejected mainstream culture and politics and expressed themselves through new and nonconventional forms of poetry. Beat scholars point to the salon-type meetings organized by Rexroth as essential to bringing the Beats together and Rexroth’s prolific writings on archaism, pacifism, mysticism, and environmentalism as influential to the themes the Beats would explore. Scholar Ann Charters also credits Rexroth’s writings on Asian philosophy as influencing the Beat writers’ interest in “Buddha consciousness.”

Mainly, however, it was his rejection of mainstream culture that aligned him with the Beat movement early on. For example, in 1951, several years before the reading at Six Gallery, Rexroth’s poem “The Dragon and the Unicorn,” was published by influential editor James Laughlin in his New Directions in Prose and Poetry. In a syndicated review the critic W. G. Rogers noted that the writers were reacting to the post-war period with disgust. Rogers wrote, “In disapproving, however, they make their most impressive claims to our attention.” He stated that though in their writing style, they “appear to throw tradition overboard,” their rebellion makes them part of a long tradition of creativity. He calls Rexroth’s poem, “the finest piece in the volume.” These themes influenced and preceded the Beat movement.

On October 7, 1955, at a poetry reading at the Six Gallery in San Francisco, Rexroth introduced Allen Ginsberg who read his revolutionary poem “Howl.” Scholars often point to this as the culminating event of the San Francisco Renaissance and solidification of the Beat movement. Charters described the movement as “awakening a new awareness in the audience (at the Six Gallery) of the large group of talented young poets in the city, and giving the poets themselves a new sense of belonging to a community.”

Rexroth championed many of the new writers in a 1957 article for The Nation, including high praise for Allen Ginsberg. He described the scene at the height of the movement:

Poetry readings to large and enthusiastic audiences are at least weekly occurrences – in small galleries, city museums, community centers, church social halls, pads and joints, apartments and studios, and at the very active Poetry Center at San Francisco State College, which also imports leading poets . . . Poetry out here, more than anywhere else, has a direct, patent, measurable, social effect, immediately grasped by both poet and audience.

In a 1958 United Press article, journalist Fred Danzig described the movement and why it became popular:

How and why did the “Beat Generation” get that way? Most writers who have dug into the subject agree that it took a world war, the Korean conflict, the cold war, hydrogen bombs, missiles and the draft. The combination made it difficult for young men to plan ahead and many of these fellows, ranging in age from 18 to mid-30s, developed a deeply-felt gloom-and-doom attitude about our world . . . While they rebel, they’re not part of a revolution. They’re not out to change the world as much as they’re out to pull away from it, disengage . . .

However, Rexroth argued that the Beat movement started as a radical literary movement, but quickly turned into a hipster lifestyle. Rexroth originally supported the Beats, feeling they shared his disenchantment with mainstream culture. However, he soon distanced himself from the movement because he felt the East Coast Beats, and especially Jack Kerouac were opportunists seeking fame and mainstream acceptance, according to Charters. Rexroth was quoted by a reporter in 1958: “This beat thing, which is a publicity gimmick in the hands of Madison Avenue, will die away…”

Writing for San Francisco Magazine in the 1970s, Rexroth looked back on the movement: “By 1955, a large school of San Francisco poets who had rejected all connections with the pre-War establishment was making its influence felt throughout the world.” He continued, “The next five years or so were known as ‘The Beat Generation,’ which was alleged to be a San Francisco product. It was almost entirely the construction of Time and Life magazines. All the cultural activities of the San Francisco Renaissance were already well under way . . .” In another column for the magazine, he continued: “Whatever the Beats may have thought of their work, it is a scathing portrayal of a society in accelerated disintegration. The next generation would enthusiastically embrace this portrayal as a ‘life style,’ to use their own slang.”

Either way, Rexroth had directly influenced the Beat movement probably more than any one other poet. In 1958, one reporter insightfully wrote that Rexroth “seems to fix the entrance requirements.” Charters states that Rexroth was one of a handful of writers who had “sown the seeds” for the flowering of the Beat movement. She refers to Rexroth as a “mentor” for the younger Beats and “the dominant force in the cultural life of San Francisco for more than half a century.”

[7] Kenneth Rexroth, “Requiem for the Dead in Spain,” New Republic, March 24, 1937, 201, accessed ebscohost.com; Kenneth Rexroth “Fighting Words for Peace,” New Republic, October 4, 1939, 245, accessed ebscohost.com; Kenneth Rexroth, The Phoenix and the Tortoise (New York: New Directions Press, 1944); W. G. Rogers, “The Literary Guidepost: New Poetry Anthology Rounds-Up Trends of Present Day Writing,” Denton (Texas) Record-Chronicle, January 5, 1951, 4, accessed Newspapers.com; Rexroth: II, 487-491, 494-96, 499-507; Linda Hamalian, A Life of Kenneth Rexroth (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991), 84, 115; Michael Davidson, The San Francisco Renaissance: Poetics and Community at Mid-Century (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 43-44; Morgan Gibson quoted in “Kenneth Rexroth,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/kenneth-rexroth; John Palattella, “’The Heart’s Garden:’ The Day that Kenneth Rexroth Died Was Not A Dark, Cold Day,” The Nation, October 31, 2002, (November 18, 2002 Issue), https://www.thenation.com/article/hearts-garden/

Rexroth had long been a pacifist. In 1937, the New Republic journal published Rexroth’s poem “Requiem for the Dead in Spain,” lamenting the horrors of the Spanish Civil War. In 1939, the same journal published a short letter from Rexroth warning of another impending world war and that the United States would be drawn into it. Once World War II began, Rexroth continued to speak out against the war and violence in his writing, but he engaged in active opposition to the war as well.

According to Hamalian, Rexroth applied for Conscientious Objector status February 19, 1943 and during the war worked with pacifist organizations such as the Fellowship of Reconciliation, the American Friends Service Committee, and the local branch of the National Committee for Conscientious Objectors. In his autobiography, Rexroth wrote:

Our organizational activities during the war were intense enough, but they were quite different from those of the earlier thirties. Not only did we belong to the religious pacifist organization the Fellowship of Reconciliation, but we became concerned with other pacifist groups. (I should say that I have never been active as a peacetime pacifist. I think the time to actively oppose war is when war is imminent or in process.) As I mentioned, we worked with but did not join the American Friends Service Committee and often attended the small First Day unprogrammed meeting, which was held in the evacuated YWCA. I became a local representative, along with a couple of other people, of the National Committee for Conscientious Objectors. We also had poetry readings to a small group once a week in our home.

In the same volume, Rexroth described various other organizations and activities in which he was involved, including providing aid to camps of conscientious objectors. He also wrote that at one point he received a notice from his draft board that his status had been changed from 4-E, conscientious objector to 1-A, available for armed service. He wrote, “I immediately appealed. The process dragged on for over a year while the FBI investigated the claim as by law they were required to do . . . There was no question that I was a bona-fide Conscientious Objector.”

Rexroth’s practice of Buddhism, Taoism, and yoga also influenced his pacifist views and actions and he incorporated this worldview along with a belief of the transcendental power of love into his writing. In 1944, New Directions Press published Rexroth’s The Phoenix and the Tortoise. According to Rexroth scholar Morgan Gibson, in this 1944 work, Rexroth wrote from the viewpoint of "the 'integral person' who, through love, discovers his responsibility for all in a world of war, cold war, and nuclear terror." According to Michael Davidson in his monograph on the San Francisco Renaissance, The Phoenix and the Tortoise, was a “meditation on history . . . given focus by reference to an as yet untouched (but threatened) landscape.” The phoenix and tortoise were symbols of “the transcendent and temporal” as Davidson explains, or of “what survives and what perishes,” as Rexroth puts it, in a world defined by “the more spectacular failures” or humanity during the war. However, again according to Davidson, this work holds out hope for of a phoenix-like rising from the ashes through the transcendental power of love, as symbolized by “the appearance of the poet’s wife, emerging from the sea.” According to Nation literary editor John Palattella, Rexroth views the ocean as “a sanctuary, a realm of mutability that absorbs and transforms the mutilated world of war. Nature’s indifference to human death is not a threat but a source of consolation, since the ocean’s one unchanging characteristic is that it changes everything.”

[8] Executive Order 9066, February 19, 1942, General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11, National Archives, accessed https://www.archives.gov/historical-docs/todays-doc/?dod-date=219; Rexroth II: 478-91, 494-96; Hamalian, 112-114; Lisa Jarnot, Robert Duncan: The Ambassador from Venus (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012), 83-84; “Japanese Relocation during World War II,” National Archives, Educator Resources, U.S. National Archives and Records Administration, www.archives.gov/education/lessons/japanese-relocation.

After the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, some Americans began questioning the loyalty of Japanese Americans, a large number of whom lived on the West Coast, then considered the Pacific military zone. In February 1942, President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066 which relocated Japanese Americans, including native born citizens, inland, away from the zone, and confined them to internment camps. Thousands were forced to leave their homes and businesses. However, some Americans, including Rexroth, opposed internment as racist and unconstitutional.

Rexroth’s activities in opposing internment were necessarily underground and so traditional newspaper sources offer no research help. We have to rely on his autobiography and some confirmation by colleagues. Rexroth wrote in his autobiography that even before the U.S. declared war on Japan that he worried Japanese Americans would face persecution. He wrote a letter and sent it to various pacifist groups and religious groups, stating that when war was declared, “the persecution of Japanese and Americans of Japanese ancestry, because they are marked by their color and features, will be worse than that of the German-Americans of the First World War.” In the same work, Rexroth continued: “I managed to persuade them to set up a committee with the absurd title of the American Committee to Protect the Rights of Americans of Oriental Ancestry.” When Rexroth and other members of the Friends Service Committee (see previous note) got word from a “contact in the White House” about the order for internment, they “immediately got on the phones,” and got each person they called to call five more people. He also called university and political contacts and civil liberties organizations. Rexroth credited this work with mobilizing opinion in the Bay Area against internment.

Rexroth also took more direct action. Again according to his autobiography, Rexroth explained a scheme that saved several Japanese-Americans, including a personal friend, from internment. He contacted the Midwest Art Academy in Chicago, which he called a “phony correspondence school” that advertised scholarships “in cheap pulp magazines” for classes on “photo retouching, art, dress design, and knitting.” He convinced the school to sign “registration papers” for Japanese American students for a fee. He then contacted the “colonel in charge” at the “headquarters for the evacuation” in San Francisco who agreed to provide educational passes for such students despite the school’s organization being “kind of a racket.” Rexroth wrote, “We started shoveling people out of the West Coast on educational passes.” He located funding through Jewish residents of San Francisco and worked with Quakers to “set up a student relocation program.” The poet Robert Duncan confirmed the activism of Rexroth and his wife Marie in opposing internment. Duncan wrote: “By the time I came out to San Francisco in 1942 I wanted very much to meet Kenneth Rexroth and . . . wrote to him beforehand and almost the first week I was here . . . Both Marie and Kenneth Rexroth were working sort of underground to get Japanese out of this area [to avoid incarceration in internment camps]…And they were also working in the camps, . . . taking messages back and forth.”

[9] Kenneth Rexroth and Lawrence Ferlingheti, Kenneth Rexroth / Lawrence Ferlingheti with the Cellar Jazz Quintent – Poetry Readings in the Cellar, LP (Fantasy Records Catalog #7002), 1957; Ed Nyberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti, Bruce Lippincott, and Kenneth Rexroth performing at the Cellar,” photograph, 1957, Record #: (DSI-AAA)8518, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, collections.si.edu; Webster Schott, "Writers Dig The Beat Generation," Kansas City Times, February 27, 1958, 34, accessed Newspapers.com; “Kenneth Rexroth, “Jazz Poetry,” The Nation (March 29, 1958), 282 in Bradford Morrow, ed., World Outside the Window: The Selected Essays of Kenneth Rexroth (New York: New Directions, 1987), 68, accessed GoogleBooks; Peter J. Hayes, “San Francisco Is Home for ‘Beat Generation,’” Brownwood (Texas) Bulletin, April 29, 1958, 1, accessed Newspapers.com; Kenneth Rexroth, Poetry and Jazz at the Blackhawk, LP (Fantasy Records Catalog #7008), 1959; Academy of American Poets, “Kenneth Rexroth: Poetry Wedded to Jazz,” https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/text/kenneth-rexroth-poetry-wedded-jazz.

In the 1950s, Rexroth began combining his poetry with the music of local jazz groups. In San Francisco he often performed at the Cellar, which became known for jazz and poetry performances and at the Blackhawk club with jazz bands like the Dave Brubeck Quartet. Two such performances were released on vinyl in 1957 and 1959 by San Francisco record label Fantasy Records. Rexroth also toured the country, performing regularly in New York City. According to the Academy of American Poets:

Rexroth was among the first twentieth-century poets to explore the prospects of poetry and jazz in tandem. He championed jazz and its musicians, publishing appreciations of players like Charles Mingus and Ornette Coleman, defending jazz in print against critics who deemed the music less than serious, and most importantly, he played in a jazz band himself, helping to define a role for the poet in the jazz world and a role for jazz in the poetry world.

In a 1958 article for The Nation, Rexroth wrote:

What is jazz poetry? It isn't anything very complicated to understand. It is the reciting of suitable poetry with the music of a jazz band, usually small and comparatively quiet. Most emphatically, it is not recitation with "background" music. The voice is integrally wedded to the music and, although it does not sing notes, is treated as another instrument, with its own solos and ensemble passages, and with solo and ensemble work by the band alone. It comes and goes, following the logic of the presentation, just like a saxophone or piano.

In February of 1958, journalist Webster Schott wrote:

An admiration for American jazz seems to be essential for qualification in the Beat Generation. In fact, not just an admiration but a conviction that jazz represents the height of beat expression. Thus, the beat writers have begun readings from their works against backgrounds of jazz improvisation. One of the first to do it was Kenneth Rexroth, poet, translator and critic, who is still reading from his poetry with jazz accompaniment in the waterfront cafes of San Francisco . . . There is no doubt about it; music reinforces the power of poetry. Both are written for the ear. When Rexroth announced, ‘At seven tomorrow morning, An Angel of Justice will appear, And . . . he will clean up peoples messes for them” the doom of electronic piano, clarinet and French horn hangs over his words like destiny.

In the liner notes for his 1959 recording Poetry and Jazz at the Blackhawk, Rexroth wrote that jazz poetry “takes the poet out of the bookish, academic world” and returns the poetry to the realm of public entertainment. Rexroth felt that combining music and spoken word connected the audience and poet directly (as opposed to the mediation of the written word) and restored poetry to oral tradition.

[10] “California Tops U.S. with 25 of 112 Guggenheim Awards,” San Bernardino County (California) Sun, April 12, 1948, 2, accessed Newspapers.com; “Guggenheim Fund Lists 144 Awards,” New York Times, April 11, 1949, 42, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “20 Will Get Grants in Arts and Letters,” New York Times, May 5, 1964, accessed nytimes.com; “Receives Honor,” (Valparaiso, Indiana) Vidette-Messenger, April 3, 1975, 7, accessed Newspapers.com; Wolfgang Saxon, “Kenneth Rexroth, 76, Author; Father Figure to Beat Poets,” New York Times, June 8, 1982, D26, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; James Laughlin, “Remembering Kenneth Rexroth,” American Poetry Review 12:1 (January/February 1983): 18-19, accessed JSTOR; Sam Hamill and Elaine Laura Kleiner, “Sacramental Acts: The Love Poems of Kenneth Rexroth,” American Poetry Review 26:6 (November/December 1997): 17-18, accessed JSTOR; John Palattella, “’The Heart’s Garden:’ The day that Kenneth Rexroth Died Was Not A Dark, Cold Day,” The Nation, October 31, 2002, (November 18, 2002 Issue), https://www.thenation.com/article/hearts-garden/; “Kenneth Rexroth,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/kenneth-rexroth; “Kenneth Rexroth,” Academy of American Poets, https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/kenneth-rexroth.

The Poetry Foundation, which publishes Poetry magazine, described Rexroth as “a central yet independent figure in American Literature.” The Academy of American Poets noted that Rexroth “was devoted to world literature and brought public attention to poetry.” In addition to his original contributions, his translations of others’ poetry and his writings on literature such as his “Classics Revisited” column in the Saturday Review increased his importance to the literary world, according to the Academy. Writing for the Antioch Review in 1971, Gordon K. Grisby wrote:

Rexroth’s best poems yield a complex pleasure. In their directness, they give the pleasure of communication, recognition, of a man speaking to be understood. At the same time their images, whether natural or human or both . . . draw us into depths of feeling. For their clarity, beauty and humanity, they make, together, one of the significant poetic achievements of our time.

Writing for the American Poetry Review in 1997, Sam Hamill and Elaine Kleiner wrote about the diversity of his work, reserving special praise for his love poems:

By turns revolutionary and conservative, simultaneously spiritual and worldly, Asian and Western, Kenneth Rexroth created what must surely be regarded as the most original synthesis of transcendent metaphysical and erotic verse ever written by an American poet. A polyglot iconoclast, Rexroth was steeped in the world’s spiritual and literary traditions, absorbing ideas and philosophy into his poetry all his life. The author of nearly sixty books, including translations of poetry . . . and two volumes of Classics Revisited among several volumes of essays, he was one of the most original and universal literary scholars of this century.

John Palattella, the literary editor for weekly journal The Nation, to which Rexroth contributed regularly, wrote in 2002:

The author of more than fifty volumes of poetry, translations and essays, Rexroth was a talented poet and a tireless promoter of the art who reached countless people through readings, magazine columns and radio broadcasts. He instructed, cajoled and insulted some of the best and worst poetic minds of several generations.

Upon Rexroth’s death in 1982, New Directions publisher James Laughlin described him as “an American cultural monument.” The New York Times described this “poet, author, critic and translator of Chinese, Japanese and classic Greek poetry” as influential on later generations of writers. The obituary noted that he received acclaim in more radical literary and political circles and then “honors and awards from more orthodox literary corners.” Among these honors, Rexroth was awarded Guggenheim fellowships in 1948 and 1949. He was awarded a prestigious grant from the National Institute of Arts and Letters in 1964 (and was later voted into the arts organization). In 1975 the Academy of American Poets presented him the Copernicus Award in recognition of his lifetime achievement in poetry.

[11] “KPFA Program Participants: Kenneth Rexroth,” FOLIO: KPFA Program 9:5 (May 25-June 7, 1958): 1, 10, accessed https://archive.org/details/kpfafolio95paci; “Kenneth Rexroth, Classics Revisited (New York: New Directions, 1965); Kenneth Rexroth, The Alternative Society: Essays from the Other World (New York: Herder and Herder, 1970); Kenneth Rexroth, The Elastic Retort: Essays in Literature and Ideas (New York: The Seabury Press, 1973); James Laughlin, “Remembering Kenneth Rexroth,” American Poetry Review 12:1 (January/February 1983): 18-19, accessed JSTOR; Bradford Morrow, ed., World Outside the Window: The Selected Essays of Kenneth Rexroth (New York: New Directions, 1987), accessed GoogleBooks; Kenneth Rexroth, More Classics Revisited (New York: New Directions, 1989); “Review: More Classics Revisited by Kenneth Rexroth,” College Literature 16:3 (Fall 1989): 291, accessed JSTOR; Michael McClure, “Seven Things about Kenneth Rexroth,” Threepenny Review 95 (Autumn 2003): 12-13, accessed JSTOR; Ken Knabb, “Rexroth’s San Francisco Journalism,” Chicago Review 52:2/4, Sixtieth Anniversary Issue, (Autumn 2006): 137-144, accessed JSTOR; Pacific Radio Archives: A Living History, http://pacificaradioarchives.org/.

Writing for the Chicago Review, Rexroth scholar Ken Knabb looked back on the over 800 columns that Rexroth wrote for the San Francisco Examiner, the San Francisco Bay Guardian and San Francisco Magazine during the 1960s and 1970s. Knabb wrote in admiration of the diversity of topics that Rexroth covered: reviews of jazz and classical concerts, operas, films, Chinese theater, performances of Shakespeare; discussions of art, literature, fishing, architecture, drugs, wine, Civil Rights, war, and politics; observations from his world travels; arguments for the women’s liberation and ecological movements; and criticisms of the past cultural movements through which he lived and participated. Knabb concluded that “as an ensemble . . . they add up to a social document and critical commentary of remarkable range.” This range can also be appreciated in Rexroth’s collection The Alternative Society: Essays from the Other World (1970). Essays in the collection range in topic from “Disengagement: The Art of the Beat Generation” to “Community Planning” to “The Heat,” a version of an essay criticizing police that got him fired from the San Francisco Examiner in 1967.

In the 1950s and 1960s, Rexroth would share some of his cultural and literary insights and opinions on the San Francisco radio station KPFA. A regular on the station, Rexroth reviewed books, performed poetry, and participated in panel discussions on current cultural and political events. Writer and Rexroth protégé Michael McClure remembered: “I’ve watched Kenneth sitting in his front room by the window above Scott Street while he spoke his reviews of scholarly and political and religious and scientific works into the microphone of an old tape recorder, preparing them for his KPFA broadcast. He would pick up a book and hem and haw in grand style while flipping the pages and eyeing the front and back material, and then deliver a learned, unrehearsed review into the machine.”

In addition to these diverse columns, Rexroth wrote extensively on literature. In 1969, New Directions gathered several of Rexroth’s essays on literature into the popular book, Classics Revisited. The essays cover sixty works from The Epic of Gilgamesh to Homer, from traditional Japanese poetry to Shakespeare, and Dostoyevsky to Mark Twain. In 1989, he followed this work with More Classics Revisited which included Rexroth’s views on Aristotle, the Bhagavad-Gita, Blake, Yeats, Kafka, and William Carlos Williams. New Directions publisher James Laughlin explained that Rexroth was a voracious reader with a photographic memory who looked up nothing while writing such essays. One reviewer of the 1989 collection noted: “This book has no bibliography, no notes, or specific reference to modern literary critics. The reader visits each classical piece with Rexroth for a little while and learns his perspective of how and where each work fits in literary history.” Of Rexroth’s extensive literary criticism, Laughlin wrote: “His books of essays make up a college course in literature and many related subjects. He had the ability . . . to pinpoint what was seminal in the work of any writer or any field.”

[12] “Kenneth Rexroth,” California Death Index, 1940-1997, State of California Department of Health Services, Center for Health Statistics, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Kenneth Rexroth,” U.S. Social Security Death Index, 1935-2014, Social Security Administration, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Wolfgang Saxon, “Kenneth Rexroth, 76, Author; Father Figure to Beat Poets,” New York Times, June 8, 1982, accessed nytimes.com; James Laughlin, “Remembering Kenneth Rexroth,” American Poetry Review 12:1 (January/February 1983): 18-19, accessed JSTOR; “Kenneth Rexroth,” photograph of grave, Santa Barbara Cemetery, California, accessed Find-A-Grave.

Kenneth Rexroth died June 6, 1982 in Montecito, Santa Barbara County, California.

[13] Kenneth Rexroth, One Hundred Poems from the Japanese (New York: New Directions, 1955); Wallace Fowlie, “An Anthology of the Lyric,” Poetry 88:2 (May 1956), 116-188, accessed JSTOR; Kenneth Rexroth, One Hundred Poems from the Chinese (New York: New Directions Press, 1956); John L. Bishop, “Review: One Hundred Poems from the Chinese by Kenneth Rexroth,” Comparative Literature 10:1 (Winter, 1958), 61-68, accessed JSTOR; Kenneth Rexroth, Love and the Turning Year: One Hundred More Chinese Poems (New York: New Directions, 1970); Kenneth Rexroth and Ling Chung, The Orchid Boat: Women Poets of China (New York: McGraw Hill, 1972); Kenneth Rexroth, New Poems (New York: New Directions Press, 1974); Kenneth Rexroth, One Hundred More Poems from the Japanese (New York: New Directions Press, 1976); Emiko Sakurai, “Review: One Hundred More Poems from the Japanese by Kenneth Rexroth,” World Literature Today 52:1 (Winter 1978), 180-181, accessed JSTOR; Kenneth Rexroth and Ikuko Atsumi, The Burning Heart: The Women Poets of Japan (New York: Seabury Press, 1977); Kenneth Rexroth, The Morning Star (New York: New Directions, 1979); Emiko Sakurai, “Review: The Morning Star by Kenneth Rexroth,” World Literature Today 55:1 (Winter 1981): 106, accessed JSTOR; Kenneth Rexroth, Women Poets of Japan (New York: New Directions, 1982); Sam Hamill and Elaine Laura Kleiner, “Sacramental Acts: The Love Poems of Kenneth Rexroth,” American Poetry Review 26:6 (November/December 1997): 17-18, accessed JSTOR; “By Kenneth Rexroth,” New Directions, http://www.ndbooks.com/author/kenneth-rexroth/; “Kenneth Rexroth,” Poetry Foundation, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poems-and-poets/poets/detail/kenneth-rexroth.

While he did some translating of French, Swedish, and Spanish works, his main focus was translating Japanese and Chinese poetry. In the introduction to One Hundred Poems from the Chinese (1956) he wrote that he worked to create translations that were both “true to the spirit of the originals” and “valid English poems.” This was a delicate balance that reviewer John L. Bishop described in question form as “reliability or readability?” because no translation could be perfect in both respects. Rexroth often ignored the line length and meter of the original in order to preserve meaning, or sacrificed nuanced meaning to create a poem that was readable in English. He has been criticized and praised for both approaches. Either way, he was a prolific and passionate translator. In the same introduction he notes that he considers translations expressions of himself much like his original poetry. In his review of One Hundred Poems from the Japanese, Wallace Fowlie wrote for Poetry magazine, “Kenneth Rexroth’s own skillful combination of delicacy and strength is everywhere evident in this book.” In a 1976 review of One Hundred More Poems from the Japanese, Emiko Sakurai wrote, “Kenneth Rexroth has been trying for decades to accomplish what has been regarded as an impossible task – rendering Japanese and Chinese poems into acceptable English verse without losing the effects of the original. And he comes nearer to achieving the impossible with each volume . . . His success with the present book enforces many critics’ view that only poets can produce acceptable translations in verse.”

Rexroth paid special attention to translating the work of women poets starting in the 1970s in works such as The Orchid Boat: Women Poets of China (1972) and The Burning Heart: The Women Poets of Japan (1977). By this point, his own work incorporated imagery and meter learned through decades of translating Chinese and Japanese poetry and in The Morning Star (1979) he interweaved his skills as a poet and a translator to the extent that they were almost inseparable. In one part of this three-part work, titled “The Love Poems of Marichiko” Rexroth presented several erotic love poems which he explained were translations of the work of a young woman in Kyoto, where he had lived for some time. In his review of The Morning Star, Emiko Sakurai praised these poems especially as “extraordinary poems, rich and sensuous, always immediate, febrile and powerful” and called Rexroth “a poet of the first rank.” However, Sakurai may have been on to Rexroth, as the reviewer noted that “The Love Poems of Marichiko” were “ostensibly” written by a young Japanese woman. Indeed, they were actually written by Rexroth from this imagined perspective. In an article for the American Poetry Review, the writers Sam Hamill and Elaine Laura Kleiner noted the transformative power his work as a translator had on his own original work and his ability to write convincingly from the “feminized” perspective of the “invented Marichiko.” They also praised Rexroth for encouraging young women writers and establishing a scholarship for young women writers in Japan.