Location: National Avenue (US 40) and IN-59, Brazil, (Clay County), Indiana 47834

Installed 2023 Indiana Historical Bureau, Clay County Historical Society, and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters

ID#: 11.2022.1

Text

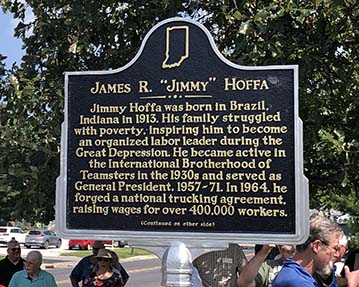

Side One

Jimmy Hoffa was born in Brazil, Indiana in 1913. His family struggled with poverty, inspiring him to become an organized labor leader during the Great Depression. He became active in the International Brotherhood of Teamsters in the 1930s and served as General President, 1957-71. In 1964, he forged a national trucking agreement, raising wages for over 400,000 workers.

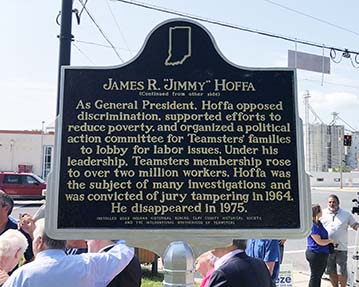

Side Two

As General President, Hoffa opposed discrimination, supported efforts to reduce poverty, and organized a political action committee for Teamsters' families to lobby for labor issues. Under his leadership, Teamsters membership rose to over two million workers. Hoffa was the subject of many investigations and was convicted of jury tampering in 1964. He disappeared in 1975.

Annotated Text

Side One:

Born in Brazil, Indiana in 1913,[1] Jimmy Hoffa became an organized labor leader during the Great Depression, having watched his family struggle in his youth.[2] He became active in the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union in the 1930s[3] and served as general president from 1957-1971.[4] In 1964, he forged a national trucking agreement, raising wages for 400,000 workers.[5]

Side Two:

Hoffa promoted political activism,[6] opposed discrimination,[7] and increased membership within the Teamsters. A subject of many investigations, including extortion, perjury, and racketeering, he was convicted of jury tampering in 1964. President Richard Nixon commuted his sentence in 1971.[8] Hoffa disappeared in 1975 after meeting with organized crime leaders.[9]

[1] “James Riddle Hoffa,” Index to Birth Records, Indiana Works Progress Administration, 1938-1940, Ancestry.com; “James Hoffa,” 1920 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com; “James Hoffa,” 1930 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com; “James Riddle Hoffa,” U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947, Ancestry.com; W. H. Hoffman’s City Directory for Brazil, Indiana, 1921, 152, Submitted by Applicant; “Profile of James Hoffa,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, October 4, 1957, 1, Newspapers.com; “Native of Brazil Remembers Hoffa,” Indianapolis News, December 31, 1971, 1, 4, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa—A Personality Profile,” Traverse City Record-Eagle, August 2, 1975, 5, Newspapers.com; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970), 1-21; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 28 ; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965), 2, 14-15, 23-25, 37; Gordon Englehart, Carolyn Branson, and Anne Carpenter, Jimmy’s Brazil, 2005, 1-13, Submitted by Applicant.

Hoffa’s birth date of February 14, 1913 is confirmed by multiple sources, including the WPA index to birth records, his WWII draft card, and both of his autobiographies, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa and Hoffa: The Real Story. He was born to parents John Hoffa and Viola Riddle Hoffa and his siblings were Jennetta, William, and Nancy Hoffa, as listed in the 1920 United States Federal Census.

His birthplace was their home on North Vandalia Street, “an A-frame house of three rooms,” of which Hoffa was born in the bedroom in the middle, according to Hoffa’s memoir, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa. They later moved to “a slightly more elegant place one block east on Ashley Street,” according to Hoffa’s official biographer, Jim Clay. Their final residence in Brazil was their home at 315 E. Church Street, as noted by the 1921 Brazil City directory and the 1920 United States Federal Census.

John Hoffa’s profession of blacksmithing was greatly buoyed by the coal mines in Clay County and the surrounding counties, according to Hoffa biographer, Jim Clay. As he wrote, “he was a mine blacksmith, meaning that he specialized in serving the metal work needs of coal mines. . . . He followed his work by muleback, making the rounds from one mine pit to another in Owen, Clay, and Putnam Counties.”

[2] “John C. Hoffa,” Indiana Death Certificates, 1899-2011, Ancestry.com; “James Hoffa,” 1930 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com James Hoffa, Detroit, Michigan, City Directory, 1930, Ancestry.com; “All Over Indiana,” Richmond Palladium, November 1, 1922, 12, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Profile of James Hoffa,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, October 4, 1957, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa—A Personality Profile,” Traverse City Record-Eagle, August 2, 1975, 5, Newspapers.com; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970), 10-12, 18; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 28-43; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965), 28-50. Gordon Englehart, Carolyn Branson, and Anne Carpenter, Jimmy’s Brazil, 2005, 1-13 Submitted by Applicant;

His father, John Hoffa, died on October 19, 1920, with his official cause of death listed as “general paralysis of insane” on his death certificate. Hoffa recalls in both of his memoirs that his father died after “four months of prolonged illness” and speculated that he might have died of a “massive stroke.”

This left young Hoffa, his siblings, and his mother Viola with the task of providing for the family. As Hoffa wrote in Trials, “She was never one to mince words. She would now have to be both mother and father to us, she said. She would have to work, she said. And we, she declared, would all have to help.” They moved back to their home on Vandalia street and began to work to make ends meet. As for her jobs during this time, Hoffa recollected in Hoffa: The Real Story, “She knew what hard work was, too, cooking in a restaurant on Main Street and doing housework in the big houses on ‘The Hill.’ My mother also took in washing, Jennetta helping with the ironing while Billy and I did the delivering.” This laundry delivery service was a large part of Hoffa’s assistance to his mother, alongside household chores involving kindling for the kitchen and transporting water for the “big clothes boiler.”

At the age of nine, the young Hoffa badly injured his right hand when “his brother missed the chicken the two were decapitating and hit his hand with the hatchet,” according to the Richmond Palladium. His hand was scarred for the rest of his life.

Regarding his childhood and its influence on his life in organized labor, Hoffa declared in Trials:

The raw courage of my mother, exemplified day in and day out while her children were growing to adulthood, has influenced my thinking, and that of my brother and sisters, perhaps more than anything else in life. Viola Riddle Hoffa's life as a mother has been the personification of the class struggle born of the Industrial Revolution. As a member of the labor movement, I am an extension of that struggle.

As an activist in the labor movement, I have dedicated myself to the creation of jobs for all who wish them and to ensuring the payment of proper compensation so that the worker can live in dignity and self-provided security. And, if there is anything about the background of the boy that influenced the life of the man, it was this.

In 1924, when Hoffa was eleven years old, the family moved to Detroit, Michigan looking for improved job prospects. Their residence in Detroit is shown in the 1930 Detroit city directory as well as the 1930 United State Federal Census.

[3] “James Hoffa,” 1940 United States Federal Census, Ancestry.com; James Hoffa, Detroit, Michigan, City Directory, 1930, Ancestry.com; “Profile of James Hoffa,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, October 4, 1957, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa—A Personality Profile,” Traverse City Record-Eagle, August 2, 1975, 5, Newspapers.com; ; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970), 22-80, ; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 27-43, 59-70; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965), 51-73.

The details of his beginning in the Teamsters union can be found in his two memoirs, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa and Hoffa: The Real Story, alongside his authorized biography by Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing.

Hoffa dropped out of school in the ninth grade and pursued work full time, working at a dry goods store named Frank and Cedar’s. Reflecting in his memoir, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa, he wrote, “My bosses liked me. I liked them. I enjoyed the work. I felt the same excitement that the department heads felt when merchandise moved well, or when a special display produced good results. I felt that I was part of a large commercial family and that each member shared each other's fortunes.” Then the Great Depression began, causing continued issues with his job at Frank and Cedar’s. He left the job and started working at a Kroger’s grocery store warehouse in 1930. It was in this job that he joined the broader labor movement. “I joined the labor movement at Kroger's,” he wrote in Trials, “I joined it out of a need for self-preservation—laced liberally with some honest anger at injustices so blatant they were obscene. ‘Man's inhumanity to man’ was constant and gleefully adhered to in the lower reaches of the economy found amidst the sweat and smells and curses and blisters of Kroger's produce warehouse.”

He and his colleagues began agitating for better pay and working conditions, essentially creating their own union within the Kroger warehouse. This came to a head in April of 1931, when 175 workers went on strike, refusing to process a shipment of strawberries. Hoffa encouraged them to join with the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union, who would provide protection during strikes. Continued conflicts with management led to him quitting his job at Kroger, but Teamsters Joint Council 43 learned of his organizing skill, bringing him in as an unsalaried organizer. In 1935, at the age 21, he became the business agent of Local 299, reorganizing and revitalizing the branch of the union, especially in its courting of truck drivers. According to biographer Jim Clay, Hoffa took the in-debt branch from a paltry 250 members to 4,000 members with money in the bank. For his efforts, he was appointed President of Local 299 in 1937.

[4] “Steel Walkout in Detroit,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, June 4, 1941, 4, Chronicling America; “Detroit Hotels Change Milk Dealers After AFL Threat,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, September 17, 1942, 1, Chronicling America; “Port Huron Milk Drivers Stage Anti-Union Strike,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, March 16, 1943, 1, Chronicling America; “Truck Drivers’ Work Stoppage is Averted,” Wilmington Morning Star, November 18, 1943, 1, 2, Chronicling America; “Union Offer to End Detroit Strike Rejected by Mayor,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, April 2, 1946, 1, Chronicling America; “Detroit Teamsters Must Join Parade or Pay $3 Fine,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, September 5, 1948, 1, Chronicling America; “Trustee’s Firing Stirs Teamsters,” Indianapolis Times, March 16, 1952, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Muscle Doesn’t Extend to the Head,” Detroit Free Press, February 8, 1953, 23, Newspapers.com; “Gang Effort Seen to Rule Trucking,” Detroit Tribune, July 23, 1955, 8, Chronicling America; “Hoffa Bullied Way to Power in Union,” Detroit Free Press, March 14, 1957, 1, 3, Newspapers.com; “17 Arrests, Three Convictions: Hoffa has had Many Brushes with Law in Stormy Career,” Detroit Free Press, March 14, 1957, 3, Newspapers.com; “Inside Washington,” Greencastle Daily Banner, April 15, 1957, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “In Driver’s Seat,” Greencastle Daily Banner, April 22, 1957, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Teamsters Confer with AFL-CIO Leaders,” Greencastle Daily Banner, May 20, 1957, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Will Run Anyway,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 29, 1957, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Vote Ban Reversed by Appeals Court in Limited Ruling,” Cincinnati Inquirer, September 29, 1957, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa’s Election Appears Certain,” Greencastle Daily Banner, October 2, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Profile of James Hoffa,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune, October 4, 1957, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Vote Challenges Congress to Protect Labor, McClellan Says,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 5, 1957, 2, Newspapers.com; “Whoop’er Up for Jimmy,” Greencastle Daily Banner, October 5, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “After a long struggle…,” Caldwell Journal, October 10, 1957, 10, Chronicling America; “On Monday morning…,” Caldwell Journal, October 17, 1957, 11, Chronicling America; “James Hoffa Takes Over Teamster President After Compromise Case,” Bedford Daily Times-Mail, January 24, 1958, 6, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters Re-Elect Hoffa As President,” Richmond Palladium-Item, July 8 1961, 1, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters Re-Elect Hoffa President,” Chicago Tribune, July 8, 1966, 1-2, Newspapers.com; “James R. Hoffa Acceptance Speech,” Teamster.org, accessed June 16, 2019, Submitted by Applicant; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 13; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970), 107-108, 113, 119, 123, 127, 154-155, 159-166, 197-198, ; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 62, 68-70, 143-150, 213; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965), 12, 112-127, 137.

During the 1940s, Hoffa found his work as business agent of the Joint Council 43 increasing dramatically, as indicated by numerous newspaper articles. As examples, in the June 4, 1941 issue of the Washington, D.C. Evening Star, Hoffa was brought in to support a steel workers’ strike in Detroit. In 1946, also chronicled by the Evening Star, he supported striking transit workers in Detroit, who wanted a 15-cent increase in pay.

At the 1952 Teamsters International Convention in Los Angeles, Hoffa was named the ninth vice president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. In his memoir, Hoffa: The Real Story, he referred his selection as vice president as “a nice step forward.”

By 1953, alongside international vice president, Hoffa juggled numerous roles within the Teamsters, including president of Truck Drivers Local 299, president of Teamsters Joint Council 43, president of the Teamsters Michigan Conference, president of the National Truckaway and Driveaway Conference, and vice president and negotiating chairman of the Central States Drivers Council, according to the Detroit Free Press.

On October 4, 1957, James R. Hoffa was elected General President of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, with a vote margin of “almost a 3-to-1 margin over his two rivals,” according to the Greencastle Daily Banner. Reflecting years later in his memoir, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa, the labor leader wrote, “I became General President of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters, the largest independent union in the world, representing a group of people to whom I gladly dedicated my life, my total devotion, my maximum effort and strength.”

As the Caldwell Journal noted, his election was highly controversial, so much so that a federal judge issued a restraining order on October 14, 1957 barring Hoffa from formally assuming the office. They alleged that delegates to the convention had been seated illegally, thereby tainting Hoffa’s election. This led to a protracted legal battle that ended on January 24, 1958, when the courts settled with the Teamsters and Hoffa formally took over as President. He was reelected in 1961 and 1966.

[5] “Auto Workers, Teamsters are Biggest Unions,” St. Louis Globe-Democrat, April 15, 1957, 28, Newspapers.com; “Profile of James Hoffa,” Logansport Pharos Tribune, October 4, 1957, 1, Newspapers.com; “Whoop’er Up for Jimmy,” Greencastle Daily Banner, October 5, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Watch on the Potomac,” Petal Paper, January 2, 1958, 3, Chronicling America; “Believes Priest’s Attack on Meany, Ill-Advised,” Catholic Times, December 5, 1958, 4, Chronicling America; “McClellan Claims Hoffa Juggles Membership Total,” South Bend Tribune, May 31, 1959, 12, Newspapers.com; “Finds Teamster Pay Tops Associate Profs’,” Detroit Tribune, March 12, 1960, 2, Chronicling America; “Teamsters Re-Elect Hoffa as President,” Richmond Palladium-Item July 8, 1961, 1, Newspapers.com;“Expelled by Federation, Teamsters in Kentucky Outgain Other Unions,” Louisville Courier-Journal, November 25, 1962, 81, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters President James R. Hoffa…,” Pascagoula Chronicle, June 24, 1963, 2, Chronicling America; “Hoffa Reported to Have Offered to Quit for End to Prosecution,” St. Louis Post-Dispatch, December 30, 1963, 1, 5, Newspapers.com; “First Master Pact Set by Truckers, Trucking Firms,” Cincinnati Enquirer, January 17, 1964, 37, Newspapers.com; “Teamster Unit to Open Talks,” Spokane Chronicle, January 18, 1964, 5, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters Approve Freight Pact,” San Francisco Examiner, January 25, 1964, 4, Newspapers.com; “Truckers Happy with Hoffa Pact,” Oakland Tribune, January 31, 1964, 18, Newspapers.com, Submitted by Applicant; “Locals Defy Hoffa Orders on Contract,” Indianapolis News, June 23, 1964, 11, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters in Revolt Against Hoffa,” Tipton Daily Tribune, June 23, 1964, 1, 6, Newspapers.com; “Anti-Hoffa Trucker Strike Spreads in East,” Minneapolis Star, June 24, 1964, 5, Newspapers.com, Submitted by Applicant; “Teamsters Re-Elect Hoffa President,” Chicago Tribune, July 8, 1966, 1-2, Newspapers.com; “Would Love Him,” Greencastle Daily Banner, July 8, 1966, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa to Ask 20c Hike for Truckers,” Indianapolis News, October 27, 1966, 34, Newspapers.com; “Pray for Hoffa,” Greencastle Daily Banner, March 8, 1967, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “’Fitz’ Set to Take Teamsters’ Helm,” Marion Star, July 6, 1971, 12, Newspapers.com; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 13; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970), 113, 119, 123, 127, 154-155, 159-166, 197-198, ; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 62, 68-70, 143-150, 213; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965), 12, 112-127, 137.

Hoffa served as general president of the International Brotherhood of Teamsters union from 1957-1971. During that time, the membership did increase, but its exact figures were disputed during his tenure. In April 1957, a few months before he became president, the membership was reported by the St. Louis Globe-Democrat as somewhere between 1,400,000 and 1,500,000, making it one of the two largest unions in the United States (the other was the United Auto Workers). The Logansport Pharos-Tribune noted 1,400,000 upon Hoffa’s election as general president while the Greencastle Daily Banner noted 1,500,000.

During the 1959 hearings of the Senate Rackets Committee, Senator John L. McClellan, Chairman, accused Hoffa and the Teamsters of “juggling figures to make it appear his union’s membership has been growing,” the South Bend Tribune noted. Using figures based on received union dues, McClellan put the membership at 1,295,740 at the end of 1957 and 1,277,000 at the end of 1958. Hoffa dismissed these numbers.

However, an article in the Helena Montana-based People’s Voice noted a membership of 1,633,000 in 1960. In 1961, in a Richmond Palladium-Item article about his reelection as general president, membership stood at 1,700,000. This number stayed the same by Hoffa’s reelection as general president in 1966, according to the Chicago Tribune.

According to Hoffa’s memoir, membership in 1970 was around 1,900,000 and a Marion Star article from July 6, 1971 placed the membership at 2,000,000. It is accurate to say that, during Hoffa’s tenure as General President of the Teamsters, the member went from approximately 1,400,000 to 2,000,000, as indicated by newspaper articles and his two memoirs.

Despite the controversies, Hoffa did receive some accolades for his leadership on behalf of workers. An editorial by Robert G. Spivack in the Petal, Mississippi-based Petal Paper praised his time in the Teamsters, declaring “he’s done more for the American labor movement than he realizes, and that’s no kidding.” In a column for the Catholic Times, a priest who supported Hoffa was quoted as saying:

for the past 12 years you have read and you have heard a many things about a Jimmy Hoffa. Let them say what they want about him, but no one can say he is not imbued with (the) spirit of unionism . . . I [wish] there were more of his qualities in the labor movement, for such alertness would stay us well in the cold battle being waged against organized labor.

Workers also experienced better pay and benefits, as noted by newspapers and Hoffa’s autobiographies. Average Teamster members often earned more than college professors, at $7,200-$7,800 a year as opposed to $7,332, a 1960 article in Detroit Tribune noted. Hoffa echoed this his memoir, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa: “Teamsters' wages continued to grow, too. We had some catching up to do, and wage increases for Teamsters exceeded the rate for all other industries.” In his second memoir, Hoffa: The Real Story, he elaborated on the benefits to Teamster members:

If you want to know how far the Teamsters have brought the nation's truck drivers, consider that in those days the highest-paid drivers were receiving $19 for a seven-day week, sunup to sundown. With our first contract we got them $.48 an hour for a sixty-hour work week, which is $28, but that was only the beginning. As of now they get $7.83 an hour, which is $469.80 for a sixty-hour week. Why sixty hours? Because overall they want to work that many hours. As one guy explained it:

"What the hell do you want me to have to do, sit around the house all the time with the old lady?"

But their benefits don't end there. Under Social Security they get $338 a month at age sixty-two. Under the Teamster pension fund they get $500 a month starting at age fifty-seven.

A 1963 article in the Pascagoula Chronicle noted that Hoffa was “weigh[ing] tax angels carefully before presenting wage demands to trucking firms this fall because union drivers are moving into higher tax brackets.”

In 1964, Hoffa played a central role negotiating the National Master Freight Agreement, which covered 400,000 Teamster members employed over 1,400 companies. The agreement provided a 36.5 to 45 cent-an-hour wage and benefit increase for the three years of the contract. The Oakland Tribune noted that “American truckers feel they struck a good bargain with Jimmy Hoffa’s Teamsters Union in the recently negotiated national master freight agreement.” Despite its largely positive reception, some locals within the Teamsters did revolt against it, citing Hoffa’s overhanded tactics against them, as articles in the Indianapolis News, Tipton Daily Tribune, and the Minneapolis Star indicated.

As his memoir and newspaper articles note, Hoffa resigned as general president on June 22, 1971, with Frank Fitzsimmons becoming interim president. Two days later, he resigned as president of Local 299 in Detroit. Hoffa would never hold another leadership position within the Teamsters.

[6] “Hoffa to Spy on Congress,” Carlsbad Current-Argus, April 10, 1960, 1, 3, Newspapers.com; “Capital Circus,” New York Daily News, September 8, 1960, 4C, Newspapers.com; “Congressional Bloc is Teamsters’ Objective,” Sheboygan Press, April 14, 1960, 5, Newspapers.com; “Union Opposition Said Not Decisive in Congress Contests,” Waterloo Courier, January 5, 1961, 4, Newspapers.com; “Teamster DRIVE Starts Slow Here,” Nashville Tennessean, August 6, 1961, 10, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters Plan Political Action in Carolinas,” Danville Bee, August 9, 1961, 31, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa’s Blonde Bombshell: His Wife Jo,” Binghamton Press and Sun-Bulletin, February 26, 1962, 11, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Tells Women: ‘You Can Control Vote’,” Racine Journal Times, April 4, 1962, 4, Newspapers.com; “A West Texan in Washington,” El Paso Times, August 24, 1963, 4, Newspapers.com; “Washington Bound,” Terre Haute Tribune, September 25, 1963, 8, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters Stress Political Buildup,” Indianapolis News, October 23, 1963, 7, Newspapers.com; “Hoffas Will Be Honored by Teamsters, Sept. 29,” Helena People’s Voice, September 13, 1963, 1, Chronicling America; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970); James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 18, 214; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965); “Teamster History Visual Timeline,” Teamster.org, accessed June 15, 2019, Submitted by Applicant.

Newspaper articles confirm that Hoffa and the Teamsters founded Democratic, Republican, Independent Voter Education (DRIVE) in 1960. It was described in the Carlsbad Current-Argus as “a neighborhood project—a major force from the rank-and-file up, not from the top down.” It’s first director was Teamster’s political action chief, Sidney Zagri. The Teamsters developed a voter outreach strategy that focused on congressional races, reported Victor Riesel in the Sheboygan Press. In the 1960 election, the Waterloo Courier wrote, DRIVE supported 233 congressional candidates, of which 137 were elected.

Jo Hoffa, the wife of James R. Hoffa, became DRIVE’s director in 1962, and “Jo Hoffa banquets” were routinely held at Teamster locals to raise funds for the political organization. As a Racine Journal Times article from April 4, 1962 noted, Jo Hoffa “urged the [5,000] women” in attendance at one of these dinners “to join your husband and fight back through DRIVE.” Female members of DRIVE would lobby their federal and local legislators. For example, the El Paso Times reported in 1963 that 170 wives of Texas Teamsters “put Texas congressmen through an inquisition on current governmental issues.” That same year, a group of five women associated with Teamsters Local 144 in Terre Haute, Indiana lobbied their federal representatives under the DRIVE banner, according to the Terre Haute Tribune.

The Teamster’s website claims that “more than 15,000 women [came] to Washington, D.C. between 1962 and 1968 to lobby for labor-related issues through the DRIVE groups.” Newspaper accounts, Hoffa’s Memoirs, and Clay’s biography do not confirm this claim. However, thousands did involve themselves with DRIVE over the years, as the sources above indicate, but it was not only women. An October 23, 1963 article in the Indianapolis News quotes Teamster associate Sidney Zagri as claiming “23,000 [members] were added in the past month.” Contradicting the claim is an article in the Saint Louis Post-Dispatch from December 30, 1963, which noted, “despite hundreds of thousands of dollars poured into this effort [DRIVE], sources close to the Teamsters operation estimate only a few thousand of the union’s 1,500,000 members are enrolled as active participants.”

[7] James R. Hoffa, “Letter to All Local Unions, Joint Councils, Area Conferences, and General Organizers,” International Brotherhood of Teamsters Archives, accessed via Instagram, June 3, 2020; “Racial Angle Bobs Up in Hoffa Trial,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 20, 1957, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Joe Louis Says He Didn’t Get a Red Cent from Hoffa Trial,” Jackson Advocate, September 7, 1957, 8, Chronicling America; “James Hoffa Charged with Ban on Negro Truck Drivers,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 18, 1959, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Teamsters Lawyer,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 5, 1959, 14, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Notifies Mitchell No Ex-Convicts Hold Offices in Teamsters,” Helena People’s Voice, February 12, 1960, 3, Chronicling America; “Jesse Owens Loses Post After Endorsing Hoffa Aide,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 29, 1961, 11, 13, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Jesse Owens Offered Job by Hoffa After Losing State Post,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 5, 1961, 11, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Calls for Labor March on Washington,” Knoxville News-Sentinel, January 30, 1963, 11, Newspapers.com; “Negroes Plan Mass March on Washington,” Shreveport Journal, May 10, 1963, 1, 6, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Aide Blasts JFK Rights Bill,” Great Falls Tribune, July 25, 1963, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Dashes Through Schedule,” Minneapolis Star, August 22, 1963, 58, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Calls Kennedy Rights Plan Farce,” Minneapolis Star Tribune, August 22, 1963, 1, 11, Newspapers.com; “Negroes March Only Beginning of Freedom Fight,” Cumberland Evening Times, August 29, 1963, 1, Newspapers.com; “March Leaders Meet with Kennedy,” La Crosse Tribune, August 29, 1963, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Suggests Members Spur to Act,” Daily Journal, August 29, 1963, 6, Newspapers.com; “Teamsters Give,” Odessa American, March 31, 1965, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Draws Fire for Aid to King,” Pittsburg Press, March 31, 1965, 5, Newspapers.com; “Wallace Hears Rights Leaders, Stifle-Easing Seen; Dickinson Charges March Marked by Immorality,” Nashville Tennessean, March 31, 1965, 1, 5, Newspaper.com; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970), 146-147; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 60; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965), 169.

James R. Hoffa’s interactions with and involvement in civil rights are complicated. In his 1957 trial for bribery, Hoffa was defended by former boxer Joe Louis, himself an African American, who testified on his behalf. “I have known Hoffa for 10 or 12 years, and in my opinion he’s a good guy,” Louis told to reporters in the Jackson Advocate. The backlash against Louis, including accusations of a payoff from Hoffa, dogged both them for years, especially the latter in the Senate Rackets Committee’s investigations. In 1961, Hoffa offered a job to Jesse Owens, famed African American Olympic runner, after his firing by the Illinois Youth Commission in 1961 for supporting a Hoffa-backed labor leader, as reported in the Indianapolis Recorder.

Within the Teamsters as an organization, Hoffa supported a non-discrimination policy as general president and outlined this policy in an April 16, 1958 letter to the membership. “As Americans, we should be opposed to bigotry and racial discrimination at every turn, and do everything in possible to make the Bill of Rights a reality for every citizen,” he wrote. This policy meant a strict non-discriminatory hiring policy at all locals within the Teamsters. However, a 1959 article in the Indianapolis Recorder noted that the Senate Rackets Committee, then investigating Hoffa, alleged that he discriminated against African Americans at his Local 299 in Detroit. It is unclear whether this claim was substantiated. That same year, the Teamsters hired Augustus G. Parker as the first African American legal counsel for the union. In the Indianapolis Recorder article announcing his hire, it was noted that “a National Bar Association resolution recently praised the union for its nondiscriminatory activities, especially in the South.” Reflecting on this later in his memoirs, Hoffa wrote: “Many inequities continued to exist in trucking circles in various parts of the nation, and I had come to realize that only a strong, solid, large union could end them. I was arguing against racism long before the federal politicians were aware of it as an issue.”

Despite the nondiscrimination policy within the Teamsters and his own declarations against racism, Hoffa did not support the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, organized by such prominent African American leaders as A. Philip Randolph of the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) and civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. Ironically, he did call for a march on Washington in 1963, but for organized labor and without any overt references to civil rights for African Americans, the Knoxville News-Sentinel reported. In an August 22, 1963 interview published by the Minneapolis Star Tribune, Hoffa called pending federal civil rights legislation “a farce and a fake” and called the March on Washington “a futile gesture.” He went on: “I do not believe that picketing will solve the problem. The march is no answer to the question of jobs.” A week later, in an almost contradictory statement, the Vineland Daily Journal quoted Hoffa saying, “Only by pressure our Congress moves . . . .These people couldn’t get anything any other way so they came to Washington to show pressure.”

By 1965, Hoffa became more public about his support for civil rights, particularly the work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. At the March 31, 1965 funeral of slain civil rights activist Viola Liuzzo, Hoffa presented King with a $25,000 check to support his civil rights advocacy, as reported by the Odessa American. Hoffa’s support of King caused a backlash within some of the rank-and-file members of the Teamsters. An article in the Pittsburg Press noted that Local 612 distributed petitions for Hoffa to ask for the check back.

The newspaper, autobiographical, and biographical sources indicate that Hoffa did support Dr. King and efforts to end discrimination within the Teamsters but wasn’t a leading voice during the civil rights movement.

[8] “Nothing Criminal,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, May 11, 1946, 6, Chronicling America; “Unionist Charged with Extortion,” Wilmington Morning Star, May 12, 1946, 2, Chronicling America; “One-Man Grand Jury Will Probe Teamsters,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, May 15, 1946, 3, Chronicling America; “Grand Jury Warrant Accuse 18 Teamsters of Extortion Plot,” Washington, D.C. Evening Star, August 18, 1946, 1, 5, Chronicling America; “Labor ‘Abuses’ are Made Public,” Wilmington Morning Star, March 2, 1947, 26, Chronicling America; “Detroit Teamster Boss Acquitted,” Indianapolis Times, June 26, 1947, 19, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Gang Effort Seen to Rule Trucking,” Detroit Tribune, July 23, 1955, 8, Chronicling America; “17 Arrests, Three Convictions: Hoffa has had Many Brushes with Law in Stormy Career,” Detroit Free Press, March 14, 1957, 3, Newspapers.com; “James Hoffa Indicted on Bribe Charge,” Greencastle Daily Banner, March 20, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Inside Washington,” Greencastle Daily Banner, April 15, 1957, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Charged with Using Funds,” Greencastle Daily Banner, May 13, 1957, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Racial Angle Bobs Up in Hoffa Trial,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 20, 1957, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Wiretap Disputes Hoffa,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 24, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “How Senate Viewed Hoffa,” Detroit Free Press, August 25, 1957, 25, Newspapers.com; “Committee Flails Hoffa for His Actions,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 26, 1957, 6, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Will Run Anyway,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 29, 1957, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Asks for a Postponement,” Greencastle Daily Banner, September 23, 1957, 6, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Indicted by Grand Jury,” Greencastle Daily Banner, September 25, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Vote Challenges Congress to Protect Labor, McClellan Says,” Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, October 5, 1957, 2, Newspapers.com; “Union Faces Senate Probe, Outer Move,” Greencastle Daily Banner, October 5, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “On Monday morning…,” Caldwell Journal, October 17, 1957, 11, Chronicling America; “AFL-CIO Official Says Labor Will Rid Itself of Corruption,” Catholic Times, October 18, 1957, 1, 2, Chronicling America; “AFL-CIO Ousts Teamsters Union,” Arizona Sun, October 31, 1957, 3, Chronicling America; “Union Setting Up a 2 Million Fund for Hoffa,” Detroit Tribune, December 7, 1957; “James Hoffa Takes Over Teamster President After Compromise Case,” Bedford Daily Times-Mail, January 24, 1958, 6, Newspapers.com; “Crime Syndicate Held Threat to Economy,” Jackson Advocate, July 26, 1958; 5, Chronicling America; “Hoffa Recalled by Probe Group,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 14, 1958, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Something Comes Out in the Wash,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 25, 1958, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Money,” Greencastle Daily Banner, September 24, 1958, 5, Hoosier State Chronicle “Not Who, But What,” Caldwell Journal, October 9, 1958, 10, Chronicling America; “Hoffa Notifies Mitchell No Ex-Convicts Hold Offices in Teamsters,” Helena People’s Voice, February 12, 1960, 3, Chronicling America; “Major Legal Victory to Teamsters’ Hoffa,” Detroit Tribune, August 6, 1960, 9, Chronicling America; “A hopelessly deadlocked jury…,” Pascagoula Chronicle, December 24, 1962, 1, Chronicling America; “A federal grand jury…,” Pascagoula Chronicle, June 4, 1963, 1, Chronicling America; “Robert Kennedy Intensifies to Nail Teamsters Boss Hoffa,” Pascagoula Chronicle, June 6, 1963, 3, Chronicling America; “Hoffa Appears in Federal Court,” Greencastle Daily Banner, June 10, 1963, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Indicted Again,” Greencastle Daily Banner, June 12, 1963, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa Assails Bobby Kennedy,” October 7, 1963, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “U.S. Rests Case in Bribery Trial of James Hoffa,” Greencastle Daily Banner, February 15, 1964, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Teamsters Boss Faces 10 Years Imprisonment,” Indianapolis Star, March 5, 1964, 1, 10, Newspapers.com; “Two Negroes Convicted with Hoffa in Jury Fixing Case,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 14, 1964, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “U.S. Examines Hoffa’s Cases,” Hackensack Record, May 12, 1964, 25, 26, Newspapers.com; “Appealing,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 22, 1964, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Court Upholds Hoffa Conviction,” Greencastle Daily Banner, July 30, 1965, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa’s Appeal to Supreme Court Rejected; Faces Prospect of Prison Within 6 Weeks,” Indianapolis Star, December 13, 1966, 2, Newspapers.com; “If Hoffa Goes to Jail, Union Will Desert Him,” Cincinnati Enquirer, December 15, 1966, 40, Newspapers.com, Submitted by Applicant; “Federal Prison Looms for Hoffa,” Greencastle Daily Banner, March 2, 1967, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Hoffa is Angry as He’s Packed Off for Prison,” Muncie Evening Press, March 7, 1967, 1, Newspapers.com; “Prison Life Agrees with Jimmy Hoffa,” Munster Times, April 24, 1967, 2, Newspapers.com; “Former Teamsters Chief Must Avoid All Unions,” South Bend Tribune, December 24, 1971, 1, Newspapers.com; “‘Model Prisoner’ Hoffa’s Friends Busy,” Indianapolis Star, January 9, 1972, 31, Newspaper.com; James R. Hoffa and Donald I. Rogers, The Trials of Jimmy Hoffa (Chicago: Henry Regnery Company, 1970), 156-159, 171-176, 201, 207-208, 297-301 ; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 64-67; 85-98, 144-148, 163-180, 214-215; Jim Clay, Hoffa: Ten Angels Swearing (Beaverdam, VA: Beaverdam Books, Inc., 1965), 1, 6-10, 90-98, 110, 143-144, 160-162.

James R. Hoffa’s interactions with the legal system stared during the 1930s, when we a young labor organizer in Detroit. An article in the Detroit Free Press from March 14, 1957 noted that Hoffa had been arrested 17 times and convicted three times, for crossing picket lines, violating anti-trust laws, and for extortion. The extortion case from 1946, wherein Hoffa allegedly “threatened damage to the property of an independent merchant,” dragged on for over a year before he was acquitted of all charges on June 26, 1947, according to the Wilmington Morning Star and the Indianapolis Times.

In 1957, Hoffa was indicted on charges of bribery. The Senate Rackets Committee, led by Senator John McClellan and Counsel Robert F. Kennedy, accused Hoffa of “bribing a rackets committee investigator to slip him secret committee documents,” the Greencastle Banner noted. Kennedy had begun investigating the labor leader a year before, which led to tense interaction between them that Hoffa recalls in his memoir, Hoffa: The Real Story. Kennedy had come into his office, unannounced, looking for documents, setting off Hoffa’s temper. As Hoffa wrote, “that incident turned out to be the start of what was to become a blood feud. Maybe it didn't seem like much at the time, but I had stepped on a poison snake.”

Hoffa faced long and penetrating investigations by the Rackets Committee. A Detroit Free Press article from August 25, 1957 reported that McClellan the committee laid out a 48-point indictment on the Teamster Vice President, accusing him of conflicts of interest, misappropriation of Teamster funds, improper loans, and questionable relationships. In regards to specific relationships, the Committee grilled Hoffa for his involvement with an ex-convict and alleged labor racketeer named Johnny Dio, who was pursuing control of a New York City taxicab union. Also in the fall of 1957, Hoffa was indicted on five counts of perjury by a federal rackets grand jury, for supposedly “lying during an investigation of wiretapping,” according to the Greencastle Daily Banner. The case was dismissed in May of 1958, with a unanimous acquittal by the jury.

Hoffa and the Teamster’s also faced opposition within the organized labor movement. On October 31, 1957, less than a month after Hoffa was elected General President of the Teamsters, the American Federation of Labor-Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) announced their intention to expel them from the umbrella union for failing to remove Hoffa and “other union officials accused of corruption.” The separation of the Teamsters and the AFL-CIO was finalized on December 6, 1957. In his memoir, Hoffa blamed Robert F. Kennedy and the Senate Rackets Committee for the AFL-CIO’s souring on him and the Teamsters. He wrote:

Then on December 6 the Teamsters were expelled from membership in the AFL-CIO because they elected me president. It really made me red-assed. Because I found out that Kennedy had whispered in a lot of the ears at the top. They sure as hell were scared they would be investigated if they crossed Kennedy. The thing that really bothered me as a lifelong union man was that it caused a split in labors unified ranks. It was back alley politics by the Kennedys. They kept most of labor on their side of the political fence for the presidential drive ahead and the Teamsters still were the patsy that would satisfy those Southern antilabor conservatives.

While Hoffa would attempt in later years to rehabilitate the Teamster’s relationship with the AFL-CIO, it was never successful.

In 1962, a mistrial was called by federal judge William Miller in another case involving Hoffa and alleged corruption. Investigators charged Hoffa “with conspiracy to receive payoff to ensure labor peace for a nationwide automobile transport firm,” as indicated by the Pascagoula Chronicle.

Robert F. Kennedy around this time had been appointed Attorney General, serving for his brother, President John F. Kennedy. Under Kennedy, the Department of Justice escalated its formal investigations on Hoffa, what the Teamster would call the “Get Hoffa Squad.” This led to numerous indictments, including a May 1962 charge of Hoffa and seven other people “fraudulently obtaining $20 million in loans from a Teamsters’ pension fund and using more than $1 million of it for their own benefit.” This action was Kennedy’s seventh legal action against Hoffa since their interactions in the Senate Rackets Committee in the late 1950s. The 55-page indictment included 28 counts of mail and wire fraud, the Pascagoula Chronicle reported. Hoffa always let his feeling about Kennedy public, as an article from the Greencastle Daily Banner illustrated. In the piece, Hoffa said, “Bobby tried to run roughshod over and I stood to up him. He is nothing but a spoiled young brat, never having had to work for a living.”

However, the case that ultimately put Hoffa in prison was a jury tampering case in Nashville, Tennessee. The Greencastle Daily Banner reported on June 10, 1963 that Hoffa and ten others were charged with bribing jurors during the previously mentioned 1962 fraud case. The trial lasted for nearly five weeks, with the government resting their case on February 14, 1964. On March 4, 1964, James R. Hoffa was found guilty on “two counts of jury tampering—crimes punishable by a total of 10 years in prison and $10,000 fine.” The Indianapolis Star reported Hoffa’s reaction to the case: “Hoffa called the verdict ‘a railroad job in my opinion’ and said he pitied ‘those who do not have the funds to go to appeals courts.’” He was sentenced to eight years and a $10,000 fine.

Hoffa appealed his case, which dragged out for another two years. The U.S. Supreme Court, on December 12, 1966, upheld Hoffa’s 1964 conviction. Hoffa began serving his prison term at the federal penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania on March 7, 1967, as noted by the Muncie Evening Press. Upon heading to prison, Hoffa said, “I hope and trust that all those who are part of that conspiracy realize the fact that it isn’t Hoffa. It’s purely a question of an American citizen. If the government can do this to Hoffa, it can do it to any American citizen.” He served a little over four years in prison before his sentence was commuted by President Richard Nixon; he was released on December 23, 1971. One of the stipulations of his release was that he could not involve himself in any union activity until March 6, 1980, the South Bend Tribune reported.

[9] “High Crime Figure Faces Questioning About Disappearance of James Hoffa,” Richmond Palladium-Item, August 1, 1975, 2, Newspapers.com; “Ex-Teamsters Chief Hoffa Disappears,” Sacramento Bee, August 1, 1975, 1, Newspapers.com; “Disappearance Latest Development in Teamster Battle,” Traverse City Record-Eagle, August 2, 1975, 5, Newspapers.com; “FBI Takes Over Now in James Hoffa Case,” Waxahachie Daily Light, August 4, 1975, 1, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa’s Children Think O’Brien Knows Something About Incident,” Jasper Herald, August 7, 1975, 22, Newspapers.com; “James P. Hoffa Now Believes His Father is Dead,” Jasper Herald, September 10, 1975, 9. Newspapers.com; “Decision Expected Today: FBI to Keep Giacalone Car?,” Jasper Herald, September 12, 1975, 21, Newspapers.com; “Hoffa Seen in Car,” Indianapolis News, December 18, 1975, 6, Newspapers.com; “James Hoffa Declared Legally Dead,” Indianapolis Star, September 9, 1982, 10, Newspapers.com; James R. Hoffa and Oscar Fraley, Hoffa: The Real Story (New York: Stein and Day, 1975), 236-242.

James R. Hoffa’s disappearance on July 30, 1975 was covered extensively in newspapers and in the last chapter of his memoir, Hoffa: The Real Story, written by co-author Oscar Fraley.

Hoffa was last seen by witnesses around 1:30 pm in front of the Bloomfield Township restaurant, according to the Sacramento Bee. Hoffa told his wife, Jo, that morning he was expecting to visit with “Tony Jack and a couple of other guys.” As Fraley noted in Hoffa: The Real Story:

“Tony Jack," also known as "Tony J." and "T. J.," is Anthony Giacalone, reputed Detroit Mafia leader who was under indictment on income-tax-evasion and mail-fraud charges. Hoffa had been called before a grand jury to testify in the Giacalone case and—something he never did in his own defense—he had taken the Fifth to keep from discussing someone else's activities.

By 4pm, Hoffa’s family and other colleagues suspected something was awry and began to ask around for help. The next day, at 6pm, he was declared missing. As Fraley wrote, “Jimmy Hoffa became a number again: Missing Person Number 75-3425.” Hoffa’s car was discovered abandoned in a Bloomfield Hills shopping center near the restaurant he was last seen by.

The FBI took over the case on August 4, 1975, according to the Waxahachie Daily Light, when “extortion demands received during the weekend turned it into a federal case.” Additionally, the Daily Light reported that threats were also made to Hoffa’s family and associates. “One FBI source said two notes had been received, one by the family and one by a Hoffa associate saying: ‘You saw what happened to him. You’re Next.’” By the fall of 1975, James P. Hoffa believed that his father was dead. “I don’t think we’ll ever see him again. I think he was assassinated,” he said to reporters in an article published by the Jasper Herald.

On December 8, 1982, over seven years after his disappearance, James Riddle Hoffa was declared legally dead. Despite being declared legally dead, the FBI continued its investigation. The Indianapolis Star reported that “the FBI said it still expects to solve the mystery of the former Teamster’s boss’ disappearance.”

Keywords

Business, Industry, & Labor