Location: Albany Community Library, 105 Broadway St., Albany (Delaware County), Indiana 47320

Installed 2022 Indiana Historical Bureau, Indiana Jewish Historical Society, Jewish American Society for Historic Preservation, and The Delaware County Historical Society

ID#: 18.2022.1

Learn more about James G. McDonald's warnings to world leaders about the Nazi threat and his work to rescue the persecuted Jews of Europe in a multi-part series for the Indiana History Blog.

Text

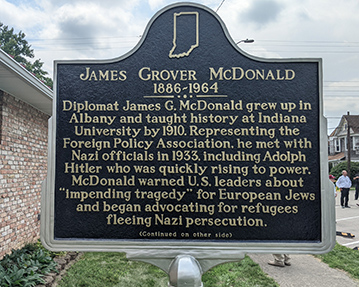

Side One

Diplomat James G. McDonald grew up in Albany and taught history at Indiana University by 1910. Representing the Foreign Policy Association, he met with Nazi officials in 1933, including Adolf Hitler who was quickly rising to power. McDonald warned U.S. leaders about “impending tragedy” for European Jews and began advocating for refugees fleeing Nazi persecution.

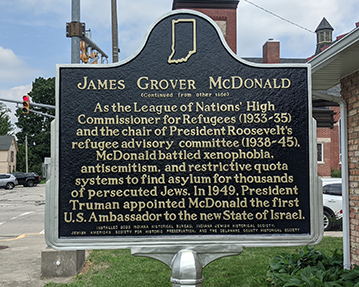

Side Two

As the League of Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees (1933-35) and the chair of President Roosevelt’s refugee advisory committee (1938-45) McDonald battled xenophobia, antisemitism, and restrictive quota systems to find asylum for thousands of persecuted Jews. In 1949, President Truman appointed McDonald the first U.S. Ambassador to the new State of Israel.

Annotated Text

James Grover McDonald, (1886-1964)[1]

Side One

Diplomat and humanitarian James Grover McDonald grew up in Albany.[2] He joined the Indiana University faculty by 1911[3] and served as chairman of the Foreign Policy Association.[4] After 1933 meetings with Nazi leaders, including Adolf Hitler,[5] McDonald warned U.S. leaders about an “impending tragedy” for European Jews[6] and began advocating for refugees from Nazi persecution.[7]

Side Two

As the League of Nations’ High Commissioner for Refugees, 1933-35,[8] and the chair of President Roosevelt’s refugee advisory committee, 1938-45,[9] McDonald battled xenophobia, antisemitism, and restrictive quota systems to find asylum for thousands of persecuted Jews.[10] In 1949, President Truman appointed McDonald the first U.S. Ambassador to the new State of Israel.[11]

[1] Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, Albany, Delaware County, Indiana, p. 8, Enumeration District: 0042, FHL microfilm: 1240368, National Archives and Records Administration, AncestryLibrary.com; “James Grover McDonald,” Passport Application, Approved August 2, 1915, Certificate: 4756, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, Ancestry Library.com; “James Grover McDonald,” Death Date: September 26, 1964, Certificate Number: 70701, New York State, U.S. Death Index, 1957-1970, AncestryLibrary.com; “James McDonald, Ex-Ambassador to Israel, Dies,” New York Times, September 27, 1964, 86, timesmachine.nytimes.com.

James Grover McDonald was born in Coldwater, Ohio, on November 29, 1886, to Kenneth and Anna McDonald. He died in New York on September 26, 1964 at age seventy-seven.

[2] Twelfth Census of the United States, 1900, Albany, Delaware County, Indiana, p. 8, Enumeration District: 0042, FHL microfilm: 1240368, National Archives and Records Administration, AncestryLibrary.com; “Albany Commencement,” Star Press (Muncie), May 6, 1905, 3, Newspapers.com; “Commencement at Albany,” Muncie Evening Press, May 5, 1905, 8, Newspapers.com; New York Department of Health, Death Certificate for James G. McDonald, Certificate Number 70701, Death Date: September 26, 1964, New York State Death Index, 1957-1970, AncestryLibrary.com; Richard Breitman, Barbara McDonald Stewart, and Severin Hochberg, eds., Advocate for the Doomed: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1932-1935 (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007), 3.

In 1898, the McDonald family moved to Albany, Delaware County, Indiana, and opened a small hotel. He worked in the hotel and attended Albany High School.

[3] “History Club,” Arbutus (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1908), 94-95, U.S. School Yearbooks, 1880-2012, AncestryLibrary.com; “Seniors,” Arbutus (Bloomington: Indiana University, 1909), 42, U.S. School Yearbooks, 1880-2012, AncestryLibrary.com; “Teaching Fellows and Assistants, 1909-10,” Indiana University Bulletin, Catalogue Number 1909, Vol. 7, No. 3 (May 1, 1909), 23-24, GoogleBooks; “Eightieth Annual Commencement,” Bloomington Evening World, June 23, 1909, 1, Newspapers.com; Thirteenth Census of the United States: 1910, Bloomington, Monroe County, Indiana (April 25, 1910), 10A, Roll: T624_371, Enumeration District: 0129, FHL microfilm: 1374384, National Archives, AncestryLibrary.com; “Department of History and Political Science,” Indiana University Bulletin, Catalogue Number 1910, Vol. 8, No. 5 (June 1, 1910), 159, GoogleBooks; “Faculty of the College of Liberal Arts,” Indiana University Bulletin, Catalogue Number 1911, Vol. 9, No. 3 (May 1, 1911), 159, GoogleBooks; “New Men Occupy Chairs,” Jackson County Banner (Brownstown), July 17, 1912, 6, Newspapers.com; “Harvard University,” Boston Evening Transcript, February 15, 1913, 9, Newspapers.com; Harvard University Gazette 9 (Cambridge: Harvard University, 1914), 216, GoogleBooks; “The Summer Session,” Indiana University Bulletin 12, No. 16 (February 1, 1915), 5, 14; “I.U. Professor,” Bedford Daily Democrat, February 23, 1915, 1, Newspapers.com; “Where They Will Spend Their Vacations,” Bloomington Evening World, June 8, 1918, 3, Newspapers.com; “Indiana University,” Bloomington Evening World, August 14, 1915, 1, Newspapers.com.

McDonald graduated from Indiana University with a B.A. in history in 1909. While pursuing his M.A. during the 1909-10 academic year, he worked as a “Teaching Fellow in History,” according to the Indiana University Course Catalogue. In 1910, he received his M.A. and continued as a Teaching Fellow. In 1911, McDonald joined the IU faculty as an “Instructor in History” for the 1911-12 academic year.

According to his daughter, McDonald went to Harvard to pursue “further doctoral work.” Newspaper articles and the Harvard Gazette show that, by 1912, he was teaching classes at Harvard during the academic year and Indiana University during the summer terms. During the 1913-14 and 1914-15 academic years he served as an Assistant Professor of History at Harvard, returning for the 1915 summer sessions at Indiana University. In February 1915, Harvard University awarded McDonald the Woodbury Lowe Traveling Fellowship “to have a year of graduate study abroad,” during the 1915-16 academic year. He studied in Spain for that year and, by fall 1916, he was serving as Professor of Greek and Roman History at Indiana University.

[4] League of Free Nations Association, “Statement of Principles,” pamphlet, November 27, 1918, 1-2, HathiTrust; League of Free Nations Association, “Do We Really Want to Prevent Future War?” broadside in Evening Star (Washington, D.C.), December 2, 1918, 13, Newspapers.com; “Urges That League Include Germany,” New York Herald, March 16, 1919, 6, Newspapers.com; “L.F.N.A.: The League of Free Nations Association,” New Republic, April 12, 1919, 357, HathiTrust; U.S. Secretary of State Alvey A. Adee to Chairman of the League of Free Nations Association James G. McDonald, September 9, 1919, Papers Relating to the Foreign Relations of the United States, 1919, Vol. 2, Office of the Historian, United States Department of State, history.state.gov; James Grover McDonald, U.S. Passport Application, Issued August 30, 1920, Certificate 85974, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1925, Roll 1345, National Archives and Records Administration, AncestryLibrary.com; League of Free Nations Association, Bulletin 2, No. 1 (March, 1921), 1, HathiTrust; Foreign Policy Association, Bulletin 2, No. 2 (June 1921), 1, HathiTrust; Foreign Policy Association, Twenty-Five Years of the Foreign Policy Association, 1918-1943, pamphlet (New York, 1943), 4, HathiTrust.

In 1918, McDonald joined the Executive Committee of the League of Free Nations Association, an organization advocating for the U.S. to join the League of Nations by influencing public opinion through lecture and educational publications. In 1919, McDonald became the Chairman of the Executive Committee of the League of Free Nations Association. In April 1921, the organization changed its name to the Foreign Policy Association, reflecting it’s broader aim to educate the public on and advocate for foreign policies to affect peace, such as global reduction of armaments. According to the FPA, “In 1922 a fundamental change took place in the work of the Association . . . placing its emphasis on education and research rather than on action . . . to act as an independent source of information on international affairs . . . emphasizing the prime importance of the study and discussion of factors entering into the character of the peace and plans for postwar reconstruction.” McDonald continued as Chairman of the FPA until 1933, when he accepted a job with the League of Nations (see note 8).

[5] James G. McDonald, [diary], April 3, 1933, April 8, 1933, in Richard Breitman, Barbara McDonald Stewart, and Severin Hochberg, eds., Advocate for the Doomed: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1932-1935 (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, Published in Association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2007), 26-28, 47-48.

As chairman of the Foreign Policy Association, McDonald met with high-ranking Nazi leaders under the assumption that there was still room for diplomacy and with the intention to advocate for the civil rights of German Jews. On April 3, 1933, McDonald met with Ernst Hanfstaengl, Hitler’s Foreign Press Chief, at the home he shared with Hermann Göring across from the Reichstag, and addressed the Nazi boycott of Jewish businesses among other civil rights violations. McDonald recorded in his diary:

Eventually we reached the subject of the Jews, especially the decree announced for Monday’s boycott. He [Hanfstaengl] defended it unqualifiedly, saying, “When I told Hitler of the agitation and boycott abroad, Hitler beat his fists and exclaimed, ‘Now we shall show them that we are not afraid of international Jewry. The Jews must be crushed.’”

McDonald continued to describe this conversation with Hanfstaengl:

He then launched into a terrifying account of Nazi plans: “The boycott is only a beginning. It can be made to strangle all Jewish business. Slowly, implacably it can be extended with ruthless and unshakeable discipline. Our plans go much further. During the war [WWI] we had 1,500,000 prisoners. 600,000 Jews would be simple. Each Jew has his SA [storm trooper]. In a single night it could be finished.

Underlining just how unthinkable a largescale genocide in a modern European country was to McDonald and most other U.S. leaders at the time, McDonald wrote in response to Hanfstaengl’s comments: “He did not explain, but I assume he meant nothing more than wholesale arrests and imprisonments.” McDonald would quickly revise this position in no small part because of his April 8, 1933 meeting with Adolf Hitler, at that time Chancellor of the German Reich. McDonald recorded in his diary that Hitler argued against criticisms of the actions taken again Jews in Germany, including boycotts of Jewish businesses and removal of Jewish professionals and government workers, under various false pretenses. McDonald recorded:

I had intended to talk about certain aspects of foreign policy first, but Hanfstaengl thought that It would be better to discuss the Jewish question directly. This I did. Immediately, Hitler replied, “We are not primarily attacking the Jews, rather the Socialists and Communists. The United States has already shut out such people. We did not do so. Therefore, we cannot be blamed if we now take measures against them. Besides, as to Jews, why should there be such a fuss when they are thrown out of places, when hundreds of thousands of Aryan Germans are on the streets? No, the world has no just ground for the complaint. Germany is not merely fighting the battle of Germany. It is fighting the battle of the world, etc.”

This battle, of course, was largely one to oppress, displace, and eventually exterminate the Jews of Germany and later Europe. McDonald expounded on these meetings when he returned to the U.S. to warn U.S. leaders. [See footnote 6.]

[6] McDonald, [diary], April 8, 1933, editor’s note in Advocate for the Doomed, 48; McDonald, [diary], May 1, 1933 in Advocate for the Doomed, 59-64; McDonald, [diary], May 2, 1933 in Advocate for the Doomed, 65, fn23; James Grover McDonald to Eleanor Roosevelt, July 24, 1933, in Advocate for the Doomed, 76-77.

After his 1933 meetings with Nazi officials (see footnote 5), McDonald returned to warn important U.S. religious and political leaders, as well as influential economic and academic leaders of Hitler’s power and planned persecution of Jews. McDonald told the influential Rabbi Stephen Wise: “His [Hitler’s] word to me [McDonald] was, ‘I will do the thing the rest of the world would like to do. It doesn’t know how to get rid of the Jews. I will show them.’” McDonald also quoted Hitler to banker and financial advisor James Warbug as stating: “I’ve got my heel on the necks of the Jews and will soon have them so they can’t move.” On May 1, 1933, McDonald had a long meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt, impressing on him the dire need for a diplomatic attempt to moderate Hitler’s extremism. In a July 24 letter to his friend Eleanor Roosevelt he wrote:

Not since my visit to Germany in March and April 1933 – about which I told you and the President on my return home – have I had as deep a sense of impeding tragedy as now. Unless present tendencies are sharply reversed, the world will be faced in the near future with the problem of another great exodus of refugees from Germany . . . It is mu conviction that the party leaders in the Reich have set for themselves a program of gradually forcing the Jews from Germany by creating conditions which make life unbearable . . . The news of the last few weeks brings confirmation . . . Under these circumstances I wonder how long the governments of the world can continue to act on the assumption that everything which is taking place in Germany and the threat implicit in such developments, are matters purely of domestic concern? . . . And is not the refusal to face it now, giving aid and encouragement to the extremist forces within the Reich? In short . . . the American government should take the initiative in protesting against the prevailing violations of elementary civil and religious rights in Germany.

McDonald also met with several State Department officials, religious leaders, Jewish organizations, politicians (at the state and federal level), and diplomats. He pressed upon them that Hitler’s power was growing, despite rumors to the contrary. He also gave public speeches, attempted to organize Jewish and Christian groups to help German Jews, and called for leaders to prepare to help refugees from Nazi persecution. For examples of these meetings and talks, see McDonald’s diary entries in Chapters 3 and 4 of Advocate for the Doomed.

[7] James G. McDonald to M. G. W. [Mildred Wertheimer] August 22, 1933, in Advocate for the Doomed, 85-89; “Governor Lehman Opens New York Joint Distribution Committee Drive for German Jews,” Modern View (Saint Louis, MO), June 22, 1933, 10, Newspapers.com; “Gov. Lehman Opens New York Drive for German Jews,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle (Milwaukee), June 23, 1933, 1, Newspapers.com; “What Lies Behind Hitlerism? What Lies Behind War?” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle (Milwaukee), August 4, 1933, 3, Newspapers.com.

As the number of refugees fleeing Nazi persecution increased in 1933, McDonald began to advocate for governments (U.S. and European) and the League of Nations to act in offering asylum. Not content with meetings and petitions, he also helped organize religious and charitable groups to meet the rising needs of asylums seekers and made public appeals for aid. His work intensified once he took the refugee commissioner position with the League of Nations later that year. [See footnote 8.]

[8] Consul at Geneva to the Secretary of State, October 26, 1933, in Foreign Relations of the United States Diplomatic Papers 1933, Vol. II (Washington: United States Government Printing Office, 1949), 373; “Jewish Refugee Commissioner,” Boston Globe, October 26, 1933, 1, Newspapers.com; “U.S. to Aid Reich Refugee Relief; J.G. McDonald Heads World Move,” New York Times, October 27, 1933, 1, accessed timesmachine.nytimes.com; “M’Donald Named as Refugee Chief,” New York Times, October 27, 1933, 10, accessed timesmachine.nytimes.com; “J. G. McDonald in Geneva,” New York Times, November 12, 1933, 2, accessed timesmachine.nytimes.com; “McDonald Organizes Body to Aid Refugees,” New York Times, November 14, 1933, 14, accessed timesmachine.nytimes.com; “James G. McDonald Poses on the Deck of the SS Paris,” photograph, 1933, Number: 58568, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed collections.ushmm.org/search/catalogue/pa1151941; “Photo Clipping from the New York Times, Photogravure Picture Section,” October 21, 1934, Number: 64428, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed collections.ushmm.org/search/catalogue/pa1154435; “Mobilizing American Jewry to Aid Jews in Germany,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, May 25, 1934, 6, Newspapers.com; “United Jewish Appeal in Hazleton,” (Hazleton, Pennsylvania) Standard-Sentinel, June 11, 1934, 8, Newspapers.com; Robert Stone, “The Voice of Hope,” (St. Louis) Modern View, September 6, 1934, 9, Newspapers.com; “McDonald Reports 40,000 Refugees Still Homeless” and “Week in Review,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, September 21, 1934, 1, Newspapers.com; “McDonald Talk on WTMJ – WISN This Saturday” and “German Refugees in Terrible Plight Says McDonald,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, November 9, 1934, 1, Newspapers.com; High Commissioner for Refugees (Jewish and Other) Coming from Germany (McDonald) to the Assistant Secretary of State (Carr),” January 2, 1935, “Under Secretary of State (Phillips) to the American Representative on the Committee for Refugees from Germany (Chamberlain),” January 21, 1935, “American Representative on the Committee for Refugees from Germany (Chamberlain) to the Under Secretary of State (Phillips),” January 23, 1935, “Secretary of State to the Secretary General of the High Commission for Refugees (Jewish and Other) Coming from Germany (Wurfbain),” January 24, 1935, “Secretary of State to American Diplomatic Representatives in South America,” February 12, 1935, “Under Secretary of State (Phillips) to the American Representative on the Committee for Refugees from Germany (Chamberlain),” February 21, 1935, “Chargé in the United Kingdom (Atherton) to the Secretary of State,” March 4, 1935, “Memorandum by the Chief of the Division of Western European Affairs (Moffat),” April 10, 1935, in Foreign Relations of the United States Diplomatic Papers 1935, Vol. II (Washington: United States Government Press, 1952), 412-413; “Jews, Driven from Germany Rebuild Lives in Other Lands,” Muncie Evening Press, July 17, 1935, 12, Newspapers.com; League is Urged to Aid Refugees,” New York Times, July 18, 1935, 1, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “League Care of German Emigres Proposed,” Fort Worth Star-Telegraph, July 18, 1935, 7, Newspapers.com; “McDonald Demands League Help for German Refugees,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, July 19, 1935, Newspapers.com; “Week in Review,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, July 26, 1935, 1, Newspapers.com; “Form $10,000,000 Company to Aid German Refugees,” Wisconsin Jewish Chronicle, July 26, 1935, 1, Newspapers.com; “Jewish Refugees Plight,” (London) Observer, July 28, 1935, 6, Newspapers.com; Breitman, Stewart, and Hochberg, Advocate for the Doomed, passim; Greg Burgess, The League of Nations and the Refugees from Nazi Germany: James G. McDonald and Hitler’s Victims (New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), Chapters 5 and 6.

In October 1933, a designated consulate of the League of Nations voted unanimously to offer McDonald the position of High Commissioner for Refugees (Jewish and Other) Coming from Germany. He arrived in Geneva November 11, 1933. McDonald was tasked with negotiating with Germany to allow a Jewish exodus, convincing countries to accept asylum seekers, coordinating the efforts of philanthropic organizations, and raising funds for all of his work.

Attempting to appease Germany, the League offered no support (diplomatic or financial) to the High Commission. While McDonald had some success raising funds and coordinating private rescue efforts, he could not find nations to accept the large numbers of asylum seekers – including the U.S. where anti-Semitism and xenophobia shaped immigration policy.

The best source for more information on McDonald’s work for the League is his journal entries reprinted in: Richard Breitman, Barbara McDonald Stewart, and Severin Hochberg, eds., Advocate for the Doomed: The Diaries and Papers of James G. McDonald, 1932-1935 (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2007).

[9] “Map Help for Refugees,” New York Times, May 17, 1938, 7, timesmachine.nytimes.com; “Committee on Refugees Elects J. G. McDonald,” Indianapolis Star, May 17, 1938, 1, Newspapers.com; “German Immigration Far Under the Quota,” New York Times, June 26, 1938, 23, timesmachine.nytimes.com; “Members of the President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees Pose with Under Secretary of State Sumner Welles After Their Meeting at the White House with Roosevelt,” photograph, 1938, Number: 06268, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, accessed collections.ushmm.org/search/catalogue/pa1032361; “May Settle Refugees in British Guiana,” Brooklyn Daily Eagle, February 1, 1939, 4, Newspapers.com; James G. McDonald, “Memorandum Recommending that the Conference of Officers of the Intergovernmental Committee on October 16-17 Be Postponed or Cancelled,” September 26, 1939, in Foreign Relations of the United States Diplomatic Papers 1939, Vol. 2 (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1956), 147-48, GoogleBooks; Drew Pearson and Robert S. Allen, “Merry-Go-Round,” Detroit Free Press, October 28, 1940, 6, Newspapers.com; “U.S. Acts to Bar 5th Columnists Among Refugees,” Chicago Tribune, December 14, 1940, 7, Newspapers.com; James G. McDonald to Sumner Welles, August 8, 1941, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 71, Folder 3, Office Correspondence, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; James G. McDonald and George L. Warren to Sumner Welles, September 30, 1942, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 80, Folder 14, Office Correspondence, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; Sumner Welles to James G. McDonald, October 2, 1942, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 80, Folder 14, Office Correspondence, Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum.

In 1938, President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed McDonald chairman of the President’s Advisory Committee on Political Refugees. In this role McDonald battled the entrenched quota system, an anti-immigrant Congress, and an obstructionist State Department to secure visas (to the U.S. and other countries) to help rescue the persecuted Jews of Europe.

[10] “War Refugees Held on Vessell,” (New Philadelphia, OH) Daily Times, September 14, 1940, 10, Newspapers.com; Stephen Wise to James G. McDonald, September 30, 1940, McDonald Papers, Columbia University, D361 (Stephen Wise Special File), Item 165, in Refugees and Rescue: The Diaries and Papers of James G. Mcdonald, 1935-1945, edited by Richard Breitman, Barbara Mcdonald Stewart, and Severin Hochberg (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2009, Published in Association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum), 208; James G. McDonald to Stephen Wise, September 10, 1940, McDonald Papers, Columbia University, D361 (Stephen Wise Special File), Item 165, in Refugees and Rescue, 209; Samuel Breckinridge Long Memo, September 12, 1940, Franklin D. Roosevelt Library, Official File 3186, in Refugees and Rescue, 209; President’s Advisory Committee Minutes, September 12, 1940, Stephen Wise Papers, Box 65, Center for Jewish History, in Refugees and Rescue, 211; McDonald to Dorothy Thompson, September 18, 1940, McDonald Papers, Columbia University, General Correspondence (Dorothy Thompson), Folder 383, in Refugees and Rescue; James G. McDonald and George L. Warren to Cordell Hull, September 23, 1940, McDonald Papers, Columbia University, D367 (PACPR), P21, in Refugees and Rescue, 212-213; James G. McDonald to Sumner Welles, January 24, 1941, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 71, Folder 3, Office Correspondence (McDonald, James G. 1941), Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; James G. McDonald to Sumner Welles, August 8, 1941, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 71, Folder 3, Office Correspondence (McDonald, James G. 1941), Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; James G. McDonald to Sumner Welles, September 22, 1942, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 80, Folder 14, Office Correspondence (McDonald, James G. 1942), Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; Sumner Welles to James G. McDonald, October 2, 1942, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 80, Folder 14, Office Correspondence (McDonald, James G. 1942), Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; James G. McDonald and George L. Warren to Sumner Welles, December 1, 1942, Sumner Welles Papers, Box 80, Folder 14, Office Correspondence (McDonald, James G. 1942), Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum; Fifty-Sixth Meeting of the President’s Advisory Committee for Political Refugees, December 1, 1942, McDonald Papers, Columbia University, D367 (PACPR), P66, in Refugees and Rescue, 337; Richard Breitman, “Conclusion,” in Refugees and Rescue, 329-338.

McDonald met with major failures throughout his career (for the reasons detailed in footnote 9), yet he helped to rescue thousands of Jews from occupied Europe. McDonald won several victories. For example, leaning on his friendship with Eleanor Roosevelt, McDonald was able to push the U.S. State Department to admit 81 Jewish refugees aboard the S.S. Quanza into the U.S. in 1940. He also pushed for the admittance of prominent rabbis, rabbinical students and academics, saving the lives of over one hundred important Talmudic scholars and Jewish thinkers. McDonald was passionate about this effort. He had much respect for the cultural contributions of the Jewish people and looked at this effort as a small way of helping to preserve that culture. He also played a major role in securing visas for 5,000 Jewish children in Vichy France. This rescue effort was thwarted to some extent, but several hundred of these children made it to the U.S., partially through the efforts of the committee. Notably, McDonald was influential in the decision of the Bolivian government to accept 20,000 refugees by working with a South American business magnate who provided much of the funding. Between 1940 and 1942 alone, (not counting the refugees just mentioned here) McDonald and the Advisory Committee secured visas for 2,133 refugees who would not otherwise have found safe haven.

[11] James G. McDonald [diary], December 13-15, 1945, in To the Gates of Jerusalem, edited by Norman J. W. Goda, Barbara McDonald Stewart, Severin Hochberg, and Richard Breitman (Indianapolis and Bloomington: Indiana University, 2014, Published in Association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum), 22; Military Entry Permit to James G. McDonald Giving Him Permission to Travel Freely throughout Germany as a Member of the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry on Palestine, January 20, 1946, Photograph Number 63518A, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Digital Collections, collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1153127; James G. McDonald [diary], March 11, 1946, in To the Gates of Jerusalem, 143; James G. McDonald [diary], April 3, 1946, in To the Gates of Jerusalem, 200; Report of the Anglo-American Committee of Enquiry Regarding the Problems of European Jewry and Palestine, 1946 in To the Gates of Jerusalem, 224-27; Memorandum of Telephone Conversation, by the Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett, June 22, 1948, in Foreign Relations of the United States 1948, Vol. 5 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1976), 1131-32; Memorandum of Telephone Conversation, by the Under Secretary of State Robert A. Lovett, June 28, 1948, Foreign Relations of the United States 1948, Vol. 5 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1976), 1151-52; James G McDonald to Secretary of State, August 19, 1948, Restricted No. 38, in Foreign Relations of the United States 1948, Vol. 5 (Washington, D.C.: United States Government Printing Office, 1976), 1326-27; James G. McDonald to Harry S. Truman, July 21, 1948, in Envoy to the Promised Land, edited by Norman J. W. Goda, Barbara McDonald Stewart, Severin Hochberg, and Richard Breitman (Indianapolis and Bloomington: Indiana University, 2017, Published in Association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum), 29; Harry S. Truman to James G. McDonald, July 21, 1948, in Envoy to the Promised Land, edited by Norman J. W. Goda, Barbara McDonald Stewart, Severin Hochberg, and Richard Breitman (Indianapolis and Bloomington: Indiana University, 2017, Published in Association with the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum), 31; “U.S. to Establish Embassy in Israel,” New York Times, February 5, 1949, 6, timesmachine.nytimes.com; “Israel Approves of McDonald as U.S. Envoy,” New York Times, February 12, 1949, 2, timesmachine.nytimes.com; “Name McDonald Israel Envoy,” Lancaster (PA) New Era, February 25, 1949, 24, Newspapers.com; “Truman Selects McDonald as Israel Envoy,” (Baltimore, MD) Evening Sun, February 25, 1949, 1, Newspapers.com; “M’Donald Is Named as Envoy to Israel, New York Times, February 26, 1949, 7, timesmachine.nytimes.com; U.S. Ambassador to Israel, James G. McDonald, Poses with a Group of Israeli Children, photograph, circa 1949-1952, Photograph Number 58572, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Digital Collections, collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/pa1152119.

In 1946, President Harry S. Truman appointed McDonald to serve on the Anglo-American Commmittee of Inquiry on Palestine. McDonald was a major voice for the creation of the state of Israel. In 1948, President Truman asked McDonald to serve as U.S. Representative to Israel and the following year, on February 25, 1949, President Truman appointed McDonald the first U.S. Ambassador to Israel.

Keywords

Political, Religion, Immigration