Location: 2 W. Main St., Jamestown, Indiana 46147 (Boone Co.)

Installed 2020 Indiana Historical Bureau, Friends Lebanon Library, Boone, Sugar Creek, & Sheridan Hist. Societies, Home National, Huntington, & Farmers Banks, Jamestown, IU Alumni Assoc., & Friends

ID#: 06.2020.1

Text

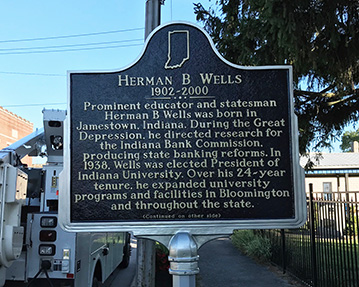

Side One:

Prominent educator and statesman Herman B Wells was born in Jamestown, Indiana. During the Great Depression, he directed research for the Indiana Bank Commission, producing state banking reforms. In 1938, Wells was elected President of Indiana University. Over his 24-year tenure, he expanded university programs and facilities in Bloomington and throughout the state.

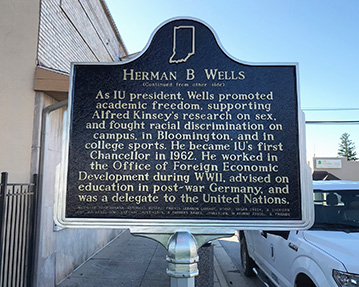

Side Two:

As IU president, Wells promoted academic freedom, supporting Alfred Kinsey’s research on sex, and fought racial discrimination on campus, in Bloomington, and in college sports. He became IU’s first Chancellor in 1962. He worked in the Office of Foreign Economic Development during WWII, advised on education in post-war Germany, and was a delegate to the United Nations.

Annotated Text

Side One

Prominent educator and statesman Herman B Wells was born in Jamestown, Indiana.[1] During the Great Depression, he directed research for the Indiana Bank Commission, producing state banking reforms.[2] In 1938, Wells was elected President of Indiana University.[3] Over his 24-year tenure, he expanded university programs and facilities in Bloomington[4] and throughout the state.[5]

Side Two

As IU president, Wells promoted academic freedom, supporting Alfred Kinsey’s research on sex, [6] and fought racial discrimination on campus, in Bloomington, and in college sports.[7] He became IU’s first Chancellor in 1962.[8] He worked in the Office of Foreign Economic Development during WWII,[9] advised on education in post-war Germany,[10] and was a delegate to the United Nations.[11]

The Minutes of the Indiana University Board of Trustees are accessible via IU Board of Trustees in collaboration with the Indiana University Archives & Indiana University Libraries Digital Collections Services, https://trustees.iu.edu/meetings-minutes/minutes.html.

[1] Death Certificate of Herman B. Wells, Indiana Death Certificates, 1899-2011, Ancestry.com; U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947 for Herman B Wells, U.S. WWII Draft Cards Young Men, 1940-1947, Ancestry.com; “Herman B Wells: 1902-2000: ‘An Indiana Treasure’,” Indianapolis Star, March 20, 2000, 1, Newspapers.com; Herman B Wells, Being Lucky: Reminiscences and Reflections (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1980), 447; James H. Capshew, “Making Herman B Wells: Moral Development and Emotional Trauma in a Boone County Boyhood,” Indiana Magazine of History, 107 (Spring 2011), 361-376.

June 7, 1902 is the generally agreed-upon date of the birth of Herman B Wells. This is on his death certificate, in his official obituary in the Indianapolis Star, and in the appendix to his memoir, Being Lucky. However, there are some discrepancies in the historical record. For example, on his WWII draft card from February 16, 1942, his birthday is listed as “June 2, 1902.” This draft card is also signed by him, making the date more complicated. However, it is safe to assume that June 7 is likely the correct date, as it is what is listed in the three sources listed above. His birthplace of Jamestown is not up for dispute, as all four sources list that. He died of congestive heart failure on March 18, 2000, at the age of 97.

His early life is chronicled well by Wells’ biographer and IU professor of history, James H. Capshew. His parents were Granville and Bernice Wells. Granville, a local banker whose profession greatly influenced young Herman, trained his son in banking procedures and delegated odd jobs to Herman at his bank. After his father’s profession took the family away from Jamestown, Herman B Wells graduated from Lebanon High School in 1920. Originally starting college in Champaign, Illinois, Wells returned to Indiana in 1921 and enrolled in Indiana University. Wells would be involved in one degree or another with IU for the rest of his life.

[2] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 6-10, 1930; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” May 16-17, 1935; “I.U. School of Commerce has 41 for Graduation,” Indianapolis Times, April 21, 1924, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Largest Class in History of I.U. Listed for Diplomas Tomorrow,” Indianapolis Star, June 5, 1927, 20, Newspapers.com; “I.U. Arranges Institute for State Bankers,” Indianapolis Times, February 1, 1930, 2, Chronicling America; “Joins Faculty,” Indianapolis Times, July 12, 1930, 2, Chronicling America, “Indiana to Strengthen Banks,” Hammond Lake County Times, December 15, 1932, 3, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “To Discuss Banking Laws,” Greencastle Daily Banner, January 10, 1933, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “M’Nutt Signs Bank Bill,” Indianapolis Times, “H.B. Wells Gets State Bank Post,” Indianapolis Star, June 14, 1933, 12, Newspapers.com; “Bankers Invite Holdup Men, Feeney Says,” Indianapolis Times, June 14, 1933, 22, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Changes Bank Jobs,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 15, 1933, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Fowler Banker is Dist. Group Head,” Greencastle Daily Banner, October 13, 1933, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles, “Lower Interest Rate Proposed to Help Banks,” Indianapolis Times, October 13, 1933, 36, Chronicling America; “Economists Set to Dissect New Deal,” Indianapolis Times, October 16, 1934, 5, Chronicling America; “M’Nutt Trains Guns on Auto Loan Sharks,” Indianapolis Times, November 26, 1934, 1, Chronicling America; “Banking Laws Discussed,” Indianapolis Times, January 15, 1935, 5, Chronicling America; “Society to Hear Wells,” Indianapolis Times, April 19, 1935, 22, Chronicling America; “Banks Advised to Loosen Up Loan Services,” Indianapolis Times, June 6, 1935, 1, Chronicling America; “Banking Code Strict,” Indianapolis Times, July 12, 1935, 20, Chronicling America; “Group to Hear State Bankers,” Indianapolis Times, March 19, 1936, 24, Chronicling America; Wells, Being Lucky, 50-67, 447; James H. Capshew, “Making Herman B Wells: Moral Development and Emotional Trauma in a Boone County Boyhood,” Indiana Magazine of History, 107 (Spring 2011), 361-376.

While administrator and statesman were professions that Herman B Wells later undertook, his first vocation was as a banker. As historian and Wells biographer James H. Capshew notes, young Herman would learn about banking and all its intricacies from his father, local banker Granville Wells. He graduated from Indiana University in 1924 with a bachelor’s degree in commerce and finance and then earned a master’s degree in economics, also from Indiana University. His master’s thesis focused on “service charges for so-called country banks.”

According to the minutes of the IU board of trustees and the Indianapolis Times, Wells joined the Indiana University faculty in 1930, as an instructor in economics and sociology. The Great Depression, begun with the stock market crash of 1929, facilitated a need for banking reform, at the federal as well as state and local levels. As Wells would later write in his memoir, Being Lucky, “the large number of [bank] failures then occurring made the subject one of urgent public concern.” Based on his experience with local banking and academic training in economics, Wells was chosen by Governor Harry Leslie to head the research department of the Indiana Banking Commission, a department created in 1931 by statute.

By the end of 1932, the commission’s work, guided by Wells’ research department, presented the Indiana General Assembly with recommendations in a 174-page report. Wells later described the broad strokes of his team’s research and recommendations:

Taking into consideration the impact of the desperate rural economic conditions, the members of the research staff and the members of the Study Commission nevertheless came to the unanimous conclusion that these failures could in large measure be eliminated by a more adequate system of state supervision and control.

This proposed system included non-partisan chartering of banks, expansion of the office of state financial institutions, both in regulatory authority as well as permanent staff and executive discretion, handling of failed banks by said office, and more incentives for banks to police themselves, as guided by the state. These recommendations resulted in a 500-page bill the General Assembly would consider in December of 1932, according to the Hammond Times.

A redraft of the bill, with Wells and his team’s assistance, continued into the early weeks of 1933, which new Governor Paul V. McNutt signed into law on February 24, 1933. As the Indianapolis Times reported, “the bill provides for a new commission of five members, but pending appointment by the Governor.” Wells was then appointed as director of research for this new commission, which was charged with implementing many of the new reforms of the 1933 banking law. As the Indianapolis Star wrote, “the new division will conduct extensive researches into banks and all allied fields with a view toward developing better banking methods in Indiana.” His role then changed in August of 1933 to “supervisor of the division of banks and trust companies,” according to the Greencastle Daily Banner.

This appointment led to continued research and further banking reforms passed in 1935, which regulated pawnbrokers, short-term lenders, and retail consumer credit, which Wells wrote was “the first comprehensive legislative regulation of time-sales financing [“finance charges in retail installment contracts”] in the nation.” As with 1933, Governor McNutt was an enthusiastic supporter of Wells’ team and their research, actively lobbying for these reforms. With this second wave of reforms, Wells’ time as research director came to an end and he resumed his duties at Indiana University, becoming Dean of the School of Business Administration in 1935.

Looking back on his banking regulation days, Wells wrote:

The creation of an effective, modern system of supervision and control for financial institutions in Indiana was not the only important result of those years. One of the happy by-products of the Study Commission’s work and of the two years invested in the rehabilitation of the financial institutions in the state was the opportunity that they provided for a group of very capable young men to get started in the field of financial institutions and later to achieve considerable success in it.

These connections and experiences would influence Wells’ life-long involvement with banking in the state as well as his later position as President of Indiana University.

[3] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 10-14, 1937; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” March 22, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” November 30-December 1, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” January 21-22, 1955; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” March 26, 1960; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” April 27, 1962; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” May 31-June 4, 1962; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 5, 1968; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” November 15, 1968; “Bryan Ends Work as I.U. President,” Greencastle Daily Banner, July 1, 1937, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Wells Takes I. U. Presidency,” Indianapolis Times, March 22, 1938, 1, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Indiana’s New President,” Muncie Post-Democrat, April 1, 1938, 4, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “To Inaugurate Dr. Wells I.U. President,” Greencastle Daily Banner, November 8, 1938, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Dr. Herman B. [Sic] Wells,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 16, 1960, 10, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Confer Title of Chancellor on Herman B Wells,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune June 18, 1962, 8, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “Indiana U. Inaugurates New President Monday,” Terre Haute Tribune Star, November 18, 1962, p. 35, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “Hail! The New Chief at I. U.,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 24, 1962, p. 10, Hoosier State Chronicles; “I.U. Trustees Begin Search for President,” Greencastle Daily Banner, July 9, 1968, 5, Hoosier State Chronicles; “J. L. Sutton Named 13th I.U. President,” Indianapolis News, November 15, 1968, 1, Newapapers.com; “The Inaugural Address, Delivered by President Herman B Wells at His Inauguration on December 1, 1938,” in, Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer, Volume IV: Historical Documents Since 1816, Thomas D. Clark, Ed. (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1977), 384; “Inaugural Address of President Elvis J. Stahr, Jr.,” in, Indiana University: Midwestern Pioneer, Volume IV: Historical Documents Since 1816, 739; Wells, Being Lucky, 94, 105.

The exact duration of Herman B Wells’ term as president of Indiana University is complicated. On May 27, 1937, the Board of Trustees unanimously chose Wells for the title of acting president, temporarily replacing outgoing President Dr. William Lowe Bryan, who had resigned. Wells’ term as acting president would begin on July 1, 1937. Bryan was enthusiastic about Wells taking the helm, saying to the Daily Banner, “I gladly resign the responsibilities of office to a man who is an unexcelled executive and a right-hearted man.” At the time, according to the Greencastle Daily Banner, Wells’ appointment was regarded as temporary, as “the board of trustees is taking immediate steps to select a permanent president of Indiana University at the earliest possible moment.” Wells himself originally saw his role as temporary, writing in his memoir, Being Lucky, “I told Judge [Ora] Wildermuth [Chairman of the I.U. Board of Trustees] that I would undertake the acting presidency if he would promise not to consider me for the position of president.”

One candidate under consideration for the permanent position was Indiana Governor Paul V. McNutt, former Dean of the university’s law school, but he would withdraw his consideration for the post. The board of trustees then interviewed many candidates for the position but found none of them to match the standard that Wells had set. As IU Board of Trustees Chairman Ora Wildermuth said to the Indianapolis Times, “as we interviewed these men, before we knew what we were doing we found ourselves using Herman as a yardstick and we soon found he had no peers.” As indicated in his memoir, Wells was reluctant to take on the role in a permanent capacity but eventually opened to it, out of a desire to benefit the university. Wells wrote, “I was persuaded finally to accept because it seemed to me further delay would be detrimental to the university.”

On March 22, 1938, the Board of Trustees unanimously elected Herman B Wells as the 11th president of Indiana University. His term began on July 1, 1938. His statement to the Trustees underscored the importance of the position and his desire to fulfill the role adequately:

I deeply appreciate the compliment you have paid me. I think I am more impressed, however, by a realization of the responsibility of the position than by any other feeling. In fact, to be altogether frank, I feel wholly inadequate to undertake this important task. I told Dr. Bryan as much when I talked with him in my office this morning. He assured me, however, that he was frightened by the responsibility when he was called upon thirty-five years ago to accept the office. I hope the decision made here today will prove in the years to come to be at least in a small part as wise as was the decision made by that earlier Board. There is a great opportunity here. To meet it, I shall need your cooperation very much. I shall do my best--I shall give all of my thought and energy to this work. And I pray that that will be enough.

His formal inauguration as president took place on December 1, 1938 in the men’s gymnasium on the Bloomington campus. In his inaugural address, President Wells stressed the values of education, democracy, and progress and emphasized the value of expanding the university’s resources and offerings. He closed with a meditation on community building and cooperation:

Though the problems be many and grave, they need not discourage us. The resources available for their solution are vast. Not the least of these are the friendship of community and state as evidenced by the presence here today of high state officials and friends from every walk of life, and the co-operative spirit of the institutions of higher learning as indicated by the presence here of so many of their leaders. Within the institution itself, elements of incalculable strength are to be found: the competence and loyalty of the student body; the generous devotion and keen foresight of the Board of Trustees.

Cognizant of the rich resources which are ours to command, heartened by the achievements already won in more than a century of distinguished service to state and nation, we face the future with confidence.

Wells would hold this position for the next twenty-four years, retiring as president on July 1, 1962. The board of trustees planned for his retirement as early as 1955, when a retirement plan was developed and implemented. Wells had also brought to the board his intention to retire as president at the March 26, 1960 trustee meeting, but action on the item was deferred to another date. Nevertheless, the Indianapolis Recorder ran an editorial on April 16, 1960 about Wells’ impending retirement, stating “the recently announced decision of Dr. Herman B Wells to step down in two years as president of Indiana University comes as a distinct shock to those of us who have watched the work of this capable educator and administrator over the last quarter-century.”

For nearly two years, the university searched for Wells’ replacement, finally choosing Dr. Elvis J. Stahr, then Secretary of the Army, Department of Defense, on April 27, 1962. Wells’ final day as President of Indiana University was July 1, 1962, when Stahr assumed the office. During his formal inauguration on November 19, 1962, Stahr laid out the immense charge he had as the new president while paying homage to his predecessor, who he called “one of the great educational statesmen of the twentieth century.” However, Wells would serve as acting president again after Stahr’s resignation on July 5, 1968, an appointment he took “with regret,” according to the Greencastle Daily Banner. He maintained this role alongside his position as Chancellor until November 30, 1968, when newly chosen President Joseph Lee Sutton took over the role.

Therefore, while it would be accurate to say that he served as president from 1938-1962, this does not account for his time as acting president in 1937 and 1968.

[4] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” May 9-10, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 9, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 30, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” September 9-10, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” October 10, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 30-July 1, 1940; “Six-Ton, $20,000 Mural History of State Decaying at Fair Grounds Awaiting Home Big Enough to Hold It,” Indianapolis Times, February 8, 1938, 1, 5, “Benton in Indiana,” Hammond Times, October 30, 1938, 4, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “I.U. Dedicates $1,170,000 Auditorium,” Indianapolis Star, March 23, 1941, 1, 10, Newspapers.com; “Indiana University Dedicates New Auditorium,” Muncie Star Press, March 23, 1941, 4, Newspapers.com; Wells, Being Lucky, 100, 105-106.

Thomas Hart Benton, noted Indiana artist, pained a series of murals showing the history of Indiana for the 1933-34 World’s Fair in Chicago. When the fair closed, the $20,000, six-ton murals were stored in the Manufacturer’s Building at the Indiana State Fair Grounds, according to the February 8, 1938 issue of the Indianapolis Times. The Times quoted Wilber D. Peat, Director of the John Herron Art Institute, saying, “certainly art patrons would like to have this history where it could be seen.” A permanent home was also considered in the Times article. Ross Teckemeyer, examiner of the State Board of Accounts, said, “I’ll turn them over to any responsible party. All they need is a building to put them in.”

Herman B Wells, newly appointed IU President, believed that the university would be a good home for the murals. He brought a proposal for the university to take possession and display of them in the Assembly Hall, which had been slated for demolition. The board approved this action in May of 1938. A month later, the board implemented a plan to renovate Assembly Hall at a cost of $3,500-$4,000 and to gain approval from Governor M. Clifford Townsend.

The trustees and President Wells quickly abandoned the Assembly Hall plan when, during a special session of the Indiana General Assembly, funding for special projects in coordination with the federal Public Works Administration (PWA) was being debated. Wells and Purdue President Edward Elliot used this opportunity to lobby for the funding of new auditoriums for each university, which was successfully earmarked by the legislature. The new auditorium project was approved by the IU board of trustees on July 30, 1938, with architect A. M. Strauss charged with developing “preliminary plans and outline specifications” for the PWA grant. Indiana University received the federal PWA funding and approved its use for the completion of the new auditorium in September of 1938. A month later, President Wells confirmed to the board that Governor Townsend approved the moving of the murals to Indiana University for installation in the new auditorium. Confirmation of the plan was published by the Hammond Times on October 30, 1938.

At a final cost of $1,170,000, the new auditorium, with the Benton murals installed, was dedicated on March 22, 1941, according to the Indianapolis Star. Panels were placed in the appropriately named “hall of murals” as well as in the 400-seat auditorium theater, the Muncie Star Press reported. In his speech that day, President Wells spoke of the murals, noting that they are “one of the most outstanding features’ of the building.”

[5] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 30, 1938; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 30-July 1, 1940; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 24-25, 1941; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” April 1, 1944; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 26, 1945; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” November 5, 1947; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 15, 1951; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” May 17, 1955; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” January 20-21, 1961; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” September 10-11, 1961; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 29, 1962; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” April 19, 1968; “County’s 32 Pupils at I.U. Looking to Annual Christmas Season,” Rushville Republican, December 15, 1937, 3, Newspapers.com; “I.U. Extension to Expand Business Curriculum,” Indianapolis Star, January 16, 1938, 8, Newspapers.com; “I.U. to Erect East Chicago Building Soon,” Munster Times, August 5, 1938, 1, Newspapers.com; “Fort Wayne Building Leased by I.U. Center,” Indianapolis Star, November 15, 1940, 13, Newspapers.com; “Kokomo to Get I.U. Extension Center School,” Kokomo Tribune, August 20, 1945, 1, Newspapers.com; “I.U. Courses Attract Nearly 100 Students,” Kokomo Tribune, September 29, 1945, 1, Newspapers.com; “New Earlham-Indiana Extension Center Opens Here January 28,” Richmond Palladium-Item, January 15, 1946, 2, Newspapers.com; “Extension School Will Start Here,” Seymour Tribune, January 30, 1946, 3, Newspapers.com; “I.U. and Gary College Unite,” Indianapolis News, June 11, 1948, 31, Newspapers.com; “New Name for Gary Extension,” Munster Times, May 16, 1949, 9, Newspapers.com; “Gary I.U. Center to Get Under Way,” Indianapolis News, August 26, 1957, 6, Newspapers.com; “I.U. to Build New $1,500,000 South Bend Extension Center,” Indianapolis Star, October 5, 1957, 11, Newspapers.com; “Wells to Speak at New I.U. Gary Center,” Indianapolis News, October 26, 1959, 6, Newspapers.com; “Wells Proposes Calumet Area Form Higher Education Council,” Munster Times, November 2, 1959, 30, Newspapers.com; “IU to Build New Kokomo Center,” Kokomo Tribune, March 22, 1961, 1, Newspapers.com; “I.U. Center Strives to Fill Need,” South Bend Tribune, March 26, 1962, 15, Newspapers.com; “I.U. Regional Centers Enroll in 11,106 Students,” Indianapolis Star, October 8, 1962, 4, Newspapers.com; “Dedicate Purdue-IU Campus at Fort Wayne,” Vidette-Messenger of Porter County, November 9, 1964, 1, Newspapers.com; “IU’s Kokomo Campus is formally Dedicated,” Kokomo Morning Times, November 13, 1965, 1, IHB File; “Goodbye IPFW, hello Purdue Fort Wayne,” Lafayette Journal & Courier, April 21, 2017, jconline.com; Robert E. Cavanaugh, Indiana University Extension: Its Origin, Progress, Pitfalls, and Personalities (1960), 28; Wells, Being Lucky, 195-211, 230-235, 459.

During his roughly 25 years as president and acting president of Indiana University, Herman B Wells oversaw a substantial expansion of the Bloomington campus as well as the extension schools around the state. As a 1962 Time magazine article notes, “Indiana’s plant has quadrupled under Wells, enrollment has quintupled to 25,000, the university’s vast research program spans everything from nuclear cloud chambers to training teachers in Thailand.” IU administrator Robert E. Cavanaugh, in his pamphlet Indiana University Extension, provides insight into Wells’ involvement of the extension schools. He writes, “since President Wells became President, the number of Centers has increased from three to 10; [and] six Centers have been enlarged and strengthened. . . .” Additionally, “the staff, small at first, larger later, and now made up of approximately 325 people (plus 508 part-time extension class teachers) has necessarily worked as a team.” Complementing Cavanaugh’s insights are enrollment statistics from newspapers. At the end of 1937, during Wells’ time as acting president, enrollment at IU extensions totaled 5,414 students, according to the Rushville Republican. By the fall of 1962, as Wells was starting his retirement from the presidency, the extensions (now called “regional campuses”) boasted an enrollment of 11,106 students, a doubling over 25 years, as reported in the Indianapolis Star.

As early as July 30, 1938, Wells was involved in a committee for the “planning of a permanent facility for the IU extension in Lake County,” today known as IU Northwest. These plans were reported in detail in the Munster Times on August 5, 1938. “Construction of the $127,000 Indiana university extension building will be started some time next month on the 2.3-acre Tod park site in East Chicago,” the Times noted. That same year he also instituted additional curriculum in business administration, which led to more faculty as well as coursework, according to the Indianapolis Star.

On July 1, 1940, President Wells presented to the IU board of trustees a plan to purchase the building then housing the Fort Wayne extension from the Lutheran School Association, which was approved pending authorization from the Governor. A “lease-purchase” agreement was finally completed on November 14, 1940, the Indianapolis Star noted. A year later, on July 24, 1941, Wells and the IU board of trustees approved the establishment of the Charlestown-Jeffersonville-New Albany Extension Center, known today as IU Southeast.

Looking to the future, President Wells presented a plan to the board of trustees on April 1, 1944 for an expansion of the IU extension schools into areas not adequately served, such as “Evansville, Vincennes, Terre Haute, Anderson-Muncie, and Richmond.” This plan of action was also approved by the trustees. In conjunction with Earlham College, the IU Richmond extension was established on January 15, 1946, as reported in the Richmond Palladium-Item. Today, it is known as IU East. Additionally, the Seymour Tribune reported on January 30, 1946 that classes would start in the university’s southwestern extension there.

One area not originally considered that eventually became a site of an extension school was Kokomo, established by the IU board of trustees on July 26, 1945. This extension would take over the Kokomo Junior College, whose finances were not adequate to continue operation. The Kokomo Tribune published a formal announcement of the extension’s founding on August 20, 1945, which quoted Wells’ view of the project. “Indiana university welcomes the opportunity to meet more directly the educational needs of Kokomo and surrounding areas,” he said. Within a little over a month, nearly 100 students had enrolled in classes at the Kokomo extension.

In the fall of 1947, Wells led discussions around expanding the Gary extension that culminated in a plan for leasing the commercial wing of the Methodist Church, approved by the board of trustees on November 5, 1947. Eight months later, on June 11, 1948, the Indianapolis News reported Wells’ announcement of the merging of the I.U. Gary extension and Gary College, with the new institution named “Indiana University Gary College.” The name was changed again to “Indiana University and Gary College Center” on May 16, 1949.

During the 1950s, President Wells continued his pursuit of permanent facilities for IU extension centers. On June 15, 1951, Wells reported to the board of trustees his intentions to make such permanent facilities a reality for the centers in Fort Wayne and South Bend. Regarding the Fort Wayne center, Purdue University also attempted to establish a center as well, which made matters complicated for Wells and the IU board of trustees. The idea of a combined campus was floated at the May 17, 1955 meeting of the board, but ultimately decided against. The merging of the two universities would happen in 1964, with a dedication of the shared campus on November 9 (that formally divided again in 2018). As for South Bend, the local Tribune reported that President Wells dedicated the new $2.5 million center on March 25, 1962, where he remarked on how the campus “is particularly response to local education needs” and thanked its director of 10 years, Jack Detzler.

Wells, along with Mayor Peter Mandich, broke ground on a new Gary center building on August 26, 1957, whose estimated cost was $2 million, as chronicled by the Indianapolis News. The facility officially opened on October 30, 1959 and was dedicated with a three-day slate of events. President Wells spoke on Sunday, November 1, on a need for a future council of higher education for the Calumet region.

In January 1961 the IU board of trustees approved purchase of 24 acres in Kokomo for the building of a new center building, at a cost of $70,000. In March of that year, the purchase was finalized and announced in the Kokomo Tribune, with Wells quoted saying “the decision of the university to relocate facilities recognizes Kokomo’s strategic position in an important area of the state.” The building was completed four years later and dedicated by Wells’ successor, Dr. Elvis J. Stahr, on November 13, 1965.

The last major decision recommended by Wells as President and approved by the board of trustees was the changing of extension center names on June 29, 1962. The extension centers would now be known as “campuses.” As an example, instead of “Indiana University Kokomo Extension Center,” it would be the “Kokomo Campus of Indiana University.” These names would stay in effect until a reorganization plan was implemented in 1968.

Reflecting on his work in expanding the university’s services across the state, Wells wrote in Being Lucky:

I think that, all in all, the system as it evolved offers to the state of Indiana the best possible program for the benefit of the students and all citizens of the state. It not only gives them a widespread coverage of academic opportunities, but does so with the least possible duplication and with the greatest efficiency involving the least cost per credit hour delivered.

[6] “Marian Anderson Sings at Concert,” Greencastle Daily Banner, April 10, 1939, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “IU President Will Discuss Education in a Democracy at YM Monster Meeting Sunday,” Indianapolis Recorder, December 2, 1939, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Of Three to Address A.M.E. Meet,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 4, 1940, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Marian Anderson Honored at Reception by A.K.A.’s,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 24, 1942, 6, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Rights Ignored—Form NAACP Branch to Gain Equal Advantage,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 10, 1945, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “At Bloomington: Student NAACP Aims for Campus Fair Play,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 6, 1945, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Strange Charge of Race Bias Made at I.U.,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 6, 1946, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “I.U. Students Approve Negro Athletes on Basketball Team,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 14, 1947, 9, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Mr. Basketball’ of 46-47 Bill Garrett, Enters I.U.,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 4, 1947, 11, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Two Way Attack Made on Segregation at I.U.,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 3, 1948, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “An Earned Recognition,” Indianapolis Star, November 22, 1948, 14, Newspapers.com; “Indiana Opens Dormitories to Colored Women,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 14, 1949, 7, Hoosier State Chronicles; “I.U. Students Plan Drive on Jim Crow,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 18, 1950; “I.U. Students Stage Drive on Jim Crow Eating Houses,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 25, 1950, 4, Hoosier State Chronicles; “State Universities Nix Sports Jimcrow,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 31, 1956, 10, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “Hoosier Big 4 Bans Segregated Games,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 31, 1956, 11, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Dr. Herman Wells, Ind. U. Joins Howard U. Board,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 2, 1956, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Martin Luther King, Integration Leader To Speak Friday at Fall Creek YMCA,” Indianapolis Recorder, December 12, 1959, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; Rachel Graham Cody, “Interview with Dorothy Collins, Long-Time Assistant/Secretary to IU President Herman Wells,” July 30, 2000, IHB File; Rachel Graham Cody, “Interview with Albert Spurlock, Former Teacher and Coach at Indianapolis Crispus Attucks High School” July 2, 2001, IHB File; Faburn DeFrantz, Unpublished Autobiography of Faburn DeFrantz, Executive Director of Indianapolis Senate Avenue YMCA, 1918-1963, 1, 95, IHB File; Letter from Elmer O’Banion to Dr. Herman B Wells, October 12, 1947, IHB File; Herman B Wells, “Speech Accepting Induction Into the IU Athletic Hall of Fame,” December 13, 1984, IHB File; Wells, Being Lucky, 214-221.

Herman Wells’ involvement in civil rights and the African American community during his time as President of Indiana University began as early as 1939, when he gave a speech in Indianapolis at the Senate Avenue YMCA’s “Monster Meeting” about “Education in a Democracy.” The Senate Avenue YMCA was an influential African American civic organization, whose “Monster Meeting” also hosted civil rights leader Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1959. In 1940, Wells co-sponsored an event at Indiana University that brought “three national leaders of the negro race . . . for a conference on community inter-racial relations,” as indicated by the Indianapolis Recorder. He also co-hosted African American singer Marian Anderson, known for her performance in front of the Lincoln Memorial in 1939, at Indiana University in 1942.

As he writes in Being Lucky, Wells understood the intense situation regarding race relations in Bloomington broadly and at Indiana University in particular:

. . . when I became President, Black students had been barred from the use of the university swimming pools. Also, the university physician using the device of a medically certified handicap to exclude them, automatically exempted Black make students from the compulsory R O T C program on the pretext that they all had flat feet. There were segregated tables for Black students in the Commons dining room of the Memorial Union Building. Black Students were not admitted to university residence halls.

To counteract these barriers, African American students on the Indiana University campus organized their own branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) on February 8, 1945. As the Indianapolis Recorder reported, “the first thing on the agenda for the newly-formed NAACP was the admittance of Negro students to state-owned dormitories on the campus.” The article also highlighted that in September of 1944, the University did provide on-campus dorms for some of its African American female students but still needed to expand this service to all African American students. Wells was quoted as saying, “there was no race issue involved, as many white students had also been denied admission.” According to Wells’ recollections, the situation was more complicated than the Recorder reported. “The administrators of our housing units,” Wells recalled, “were apprehensive that, if we admitted Black students, there would be objection, not necessarily from white students, but from their parents to the extent of seeking other housing for their sons and daughters. This fear did not prove to be justified in the case of male students, but with women students it was another matter.” These complicated matters resulted in a gradual desegregation of the dormitories, starting with women in 1949 and then applying to all students by 1952.

While housing was something Wells’ addressed in a more delayed fashion, the desegregation of the university commons and swimming pools he handled head on and quickly. As his assistant and secretary, Dorothy Collins, described in a July 3, 2000 interview:

Wells was very committed to integration. He had Rooster Crow jump in the pool. He and the Director of the Union sat in the “black section of the Union cafeteria thereby integrating it. When Bloomington taverns said they wouldn’t allow blacks, Wells said, “well then he would arrange it do IU people wouldn’t got [sic] there either.” Same with local barbershops. “They [blacks] were students, that was the most important thing and Wells wanted to see them get the same rights and opportunities as any other students.”

Wells’ memoir corroborates much of this passage, with the notable point that the student’s name was “Rooster Coffee” and not “Rooster Crow.” Regarding the commons in the Union, Wells asked its manager, James Patrick, to “unobtrusively” remove the “reserved” cards on tables for the African American students and allow people to sit wherever they wanted. “It was two weeks before anyone discovered the fact that the signs were gone and then, of course, the absurdity of the previous situation was apparent,” he wrote. As for Rooster Coffee and the swimming pool, Wells asked Athletic Director Zora Clevenger to encourage the “known football player with a wonderful personality who had won the heart of the campus” to get into the pool and swim without any concern for past policies. “He was so cordially greeted,” Wells recollects, “I doubt that anyone realized a policy had been changed. That was the last of discrimination against Blacks in the use of the pool.” The barbershops followed the same path. Wells directed that the union barbershop on campus only be leased to a proprietor who would not discriminate. Such a proprietor was found in Ed Correll, who “offered to undertake the operation of the shop on that basis with the promise that, if he could not hire barbers who would follow the policy, then he would serve the Black students himself.” The university “accepted Ed’s offer, and later the other barbershops one by one began to accept Black patrons,” Wells wrote.

The situation regarding restaurants in Bloomington was a much more complicated affair. Despite local laws that prohibited discrimination based on race, “practically none of the downtown restaurants would serve Black students,” wrote Wells. By March 1950, the local NAACP and an interracial group of students protested this de-facto segregation and attempted being served at downtown restaurants. As the Indianapolis Recorder reported, “every time they went in, the restaurants closed.” Wells, who the Recorder praised for his “democratic stand in interracial matters, reportedly pledged to use his influence against the eating-place discrimination.” His used his influence against the local restaurant association, noting that its action was “immoral but also illegal” and providing it with an ultimatum: either open up the restaurants to all or Wells would advise all faculty and students to stay on campus and eat at the Union. Wells received support from the university and Union director Harold Jordan for this action, which “resulted in the evaporation of the whole issue, and most restaurants began to serve Black customers as well as white,” as he recorded in Being Lucky.

One area in which Wells’ arguably left his most enduring impact involved IU’s athletics. Up until the mid-1940s, Indiana University participated in an “informal understanding among the basketball coaches that they would not recruit Black basketball players, a practice that now seems incredible,” he recalled. The student body also agreed that this practice was problematic, as “nine out of ten Indiana University students would approve Negro athletes playing on the university’s baseball and basketball teams,” the Indianapolis Recorder reported on June 14, 1947. This changed with the recruitment of Shelbyville High School’s “great all-state center,” Bill Garrett, to the IU basketball team in the fall of 1947. The decision to bring Garrett to the campus involved four important leaders, according to the Recorder: Faburn E. DeFrantz, executive secretary of the Senate Avenue YMCA in Indianapolis, Shelbyville businessman and former high school basketball player Nate Kaufman, Branch McCracken, I.U.’s basketball coach, and Wells.

His memoir as well as his secretary Dorothy Collins’ remarks in a 2000 interview confirm Wells’ role in the decision. As Wells discusses in Being Lucky, “some of my black friends from Indianapolis” came to see him and said that if McCracken would support recruiting Garrett, they would convince the young star to come to IU. Wells then spoke with McCracken, who was “enthusiastic” about Garrett but worried about not getting treated fairly by other Big 10 teams. Wells replied, “Let’s take him, and if there’s any conference backlash against it, then I’ll take the responsibility for handling it.” He added that if McCracken received any trouble from the other Big 10 coaches, Wells would coordinate he and the other nine college presidents to “bring the pressure” on them. The other coaches “capitulated and began to scramble for good Black players” while Garrett “made a great record as a basketball player and student.” The Senate Avenue Y.M.C.A. of Indianapolis awarded Herman B Wells the 1948 Emblem Club award, “in recognition of his concern for Negro students at the nation’s ninth largest institution of higher learning.” DeFrantz would later say in a 2000 interview that, “in Indiana University’s President Herman B Wells democracy found an ally. No overhaul of policy such as that accomplished at Indiana University could have been possible without the cooperation he gave.”

Garrett’s recruitment paved the way for Indiana University as well as the other big 10 schools to end their informal agreement against African Americans for all sports in 1956. According to the Indianapolis Recorder, the decision came as a result of the treatment of IU baseball player Eddie Whitehead, who was not allowed to play against rival teams in Florida and Georgia. In his statement, Wells “called the indignities suffered by Whitehead ‘outrageous’ and noted that ‘I.U. is the leader in the nation against segregation as well as in athletics.”

In all, Herman B Wells’ leadership, along with students, the local NAACP, African American community leaders, and members of the IU faculty and staff, led to racial barriers being dissolved and increased inclusion for African Americans on the IU campus and in Bloomington.

[7] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” September 11-12, 1943; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” August 19, 1953; Greencastle Daily Banner, August 21, 1953, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles. Wells, Being Lucky, 177-187.

A few years before Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey began his sex research in 1938, President Herman B Wells actively championed academic freedom at Indiana University. In 1943, he advised the IU Board of Trustees to adopt a formal statement on academic freedom, approved on September 11, 1943. It read:

No restraint shall be placed upon the teacher's freedom in investigation, unless restriction upon the amount of time devoted to it becomes necessary in order to prevent undue interference with other duties. No limitation shall be placed upon the teacher's freedom in the exposition of his own subject in the classroom or in addresses and publications outside the classroom so long as the statements are not definitely anti-social. No teacher shall claim as his right the privilege of discussing in his classroom controversial topics obviously and clearly outside of his own field of study. The teacher is morally bound not to take advantage of his position by introduction into the classroom of provocative discussions of completely irrelevant subjects admittedly not within the field of his study. The University recognizes that the teacher, in speaking and writing outside of the institution upon subjects beyond the scope of his own field of study, is entitled to precisely the same freedom, but is subject to the same responsibility, as attaches to all other citizens.

This balance between freedom and responsibility remained the guidepost of Wells’ tenure as President, especially regarding Dr. Kinsey. The “respected biologist and Starred Man of Science” as Wells described him, Kinsey’s research focused on documenting the sexual histories of 100,000 individuals. Early on, the IU president understood how controversial this work would be but stayed committed to the project. “For me,” Wells later wrote in Being Lucky, “there was really no question about support of Kinsey’s research. I had early made up my mind that a university that bows to the wishes of a person, group, or segment is not free.” Despite the mounting pressures against the university from outside forces, including alumni, members of the legislature, and members of the religious community, the Board of Trustees were steadfast in their protection of Kinsey and his research. As Wells boasted later, “I am proud to record the fact that, although the individual members of the board and the board as whole were harassed and subjected to all manner of pressure, they never once wavered in their support of our policy toward the Kinsey institute.”

When Kinsey prepared for the publication of his 1953 book, Sexual Behavior in the Human Female, the IU board of trustees discussed their university position on the work. The board then agreed at its August 19, 1953 meeting that “position of the University will be that, before the research leading to this and a prior publication was undertaken, the University administration and the Board of Trustees had approved the project and had pledged to defend the right of our scientists to engage in this and other research projects, inasmuch as research is the function of a university and the right to conduct research must be upheld.” A formal statement by President Wells and the board was adopted, which read:

Indiana University stands today, as it has for fifteen years, firmly in support of the scientific research project that has been undertaken and is being carried on by one of its eminent biological scientists, Dr. Alfred C. Kinsey.

The University believes that the human race has been able to make progress because individuals have been free to investigate all aspects of life. It further believes that only through scientific knowledge so gained can we find the cures for the emotional and social maladies in our society.

In support of Dr. previous hit Kinsey's research the University is proud to have as co-sponsor the National Research Council and its distinguished committee of scientists and physicians in charge of studies of this nature. With the chairman of that committee I agree in saying that we have large faith in the values of knowledge, little faith in ignorance.

This statement was published on August 21, 1953 in the Greencastle Daily Banner. Reflecting on this challenge, Wells believed that “time had proved the defense [of Dr. Kinsey] was important, not only for the understanding of sexual activity, but also for the welfare of the university.” Additionally, “it reinforced the faculty’s sense of freedom to carry on their work without fear of interference.”

[8] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” May 31-June 4, 1962; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” April 23, 1972; “Confer Title of Chancellor on Herman B Wells,” Logansport Pharos-Tribune June 18, 1962, 8, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “Indiana U. Inaugurates New President Monday,” Terre Haute Tribune Star, November 18, 1962, p. 35, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; Wells, Being Lucky, 431-445.

The Board of Trustees of Indiana University appointed Herman B Wells Chancellor of Indiana University in the summer of 1962. He would begin this appointment on July 1, 1962, his final day as president. The Board of Trustees also approved “teaching services to be performed by Dr. Wells in the School of Business under his Professorship of Business Administration.” He also expanded his role as president of the IU Foundation, a position he held since the beginning of his university presidency, “which administers gifts, grants, and bequests to the university for scholarship and research,” according to the Terre Haute Tribune Star.

As he discusses in Being Lucky, Wells received the position of Chancellor without a set course, as the Board of Trustees wanted him to develop the position in his own way. Alongside his primary duties with the IU Foundation, which were related to donor relationships and fundraising, Wells took on “ad hoc assignments as they arose,” such as chairman of the board of Education and World Affairs in New York, surveys of higher education sponsored by programs out of New York state and Michigan, consultant to Columbia University, and serving on White House Committees, including the Special Committee on U.S. Trade Relations with East European Countries, the President’s Committee on Overseas Voluntary Activities, and the Commission on the Humanities.

On July 1, 1972, Herman B Wells retired in an official capacity from Indiana University, maintaining title of Chancellor and Professor Emeritus of Business Administration until his death in 2000. In a wide-reaching interview with the Indianapolis News published on July 24, 1972, Wells expressed a desire to take a step back from duties and to continue his role as a “volunteer.” “I have many things I want to accomplish yet,” Wells declared, “but I wanted to make sure it was understood that I was not in any official line relationship. All my responsibilities from now on in will be assigned by either the president of the university or the foundation.”

[9] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 17, 1943; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” July 31, 1943; “Gets Appointment,” Greencastle Daily Banner, August 13, 1943, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Indiana University Head Named OFEC Director,” Van Wert Times Bulletin, August 14, 1943, 4, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “Wells Asks Release at Washington; Will Devote Full Time to I.U. Duties,” Indianapolis Star, January 10, 1944, 1, Newspapers.com; “Advisers Named,” Richmond Palladium-Item, November 10, 1943, 2, Newspapers.com; Wells, Being Lucky, 320-327, 449.

Wells served as Deputy Director of the federal Office of Foreign Economic Coordination (OFEC) and Special Advisor on Liberated Areas for the Office of Foreign Economic Administration (OFEA) from 1943-1944. On July 17, 1943, he requested approval for the position by the IU board of trustees. After insistence from the U.S. State Department that Wells accept the position, the IU board of trustees approved his request on July 31, 1943. The State Department then formally announced his appoint to the OFEC on August 13, 1943. In an article from the Greencastle Daily Banner, Wells’ role was to be “in charge of planning economic activities in areas liberated from the Axis.” The Van Wert Times Bulletin, in its article on the appointment, added the Wells would also “coordinate the activities of other civilian agencies in this field.” The Richmond Palladium-Item reported on November 10, 1943 that the OFEC had “been abolished” and replaced by the Office of Foreign Economic Administration. Wells would stay involved in this new organization but as Special Advisor on Liberated Areas.

Arguably Wells’ most important role during this period was as a delegate to an international conference on November 10, 1943 to organize the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, or UNRRA. As Wells wrote of the conference in Being Lucky, “we were in Atlantic City three weeks, and the resulting organization was widely hailed as an important step in planning for the future and for the rehabilitation of areas devastated by the war.”

On January 10, 1944, Wells asked the State Department to relieve him of his duties, effectively resigning from his post with OFEA, according to the Indianapolis Star. In his announcement, Wells said that “the emergency portion of the work, for which he was called to Washington last August by Secretary of State Hull, has been completed. He added that he therefore felt that university matters now should have complete priority of his time.”

[10] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 30, 1947; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” September 12-13, 1947; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” October 17-18, 1947; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 10, 1948; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” May 16-19, 1960; “I.U. President on Way to Berlin,” Indianapolis Star, July 30, 1947, 5, Newspapers.com; “I.U. Head Sought by War Department” Jeffersonville Evening News, August 13, 1947, 1, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “War Department Asks I.U. to Release Wells,” Indianapolis Star, August 17, 1947, 1, Newspapers.com; “Key Civilians Quit Posts on Reich Occupation Team,” Middletown News Herald, September 8, 1947, 5, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “Wells Receives Leave from I.U.,” Indianapolis News, October 18, 1947, 1, Newspapers.com; “Wells Takes Over as Aide to Clay,” Indianapolis Star, November 24, 1947, 1, Newspapers.com; “I.U. President Held 3 Hours by Russians,” Indianapolis Star, January 13, 1948, 1, Newspapers.com; “Wells Plan is Ready,” Indianapolis Star, February 7, 1948, 4, Newspapers.com; “Gen. Clay Charges Russ Violate Pact,” Indianapolis News, February 16, 1948; Wells, Being Lucky, 301-318.

On June 30, 1947, Herman B Wells received approval from the IU board of trustees “to make a trip to Germany . . . for the purpose of consulting with General Lucius D. Clay, United States Military Governor on matters of education in the American occupation zone of Germany.” This approval was also reported in the Indianapolis Star, who noted that this was Wells’ second visit to Europe, his first being Greece in 1946 to help oversee their elections. According to an August 14, 1947 letter from Secretary of War Kenneth C. Royal to IU Chairman of the Board of Trustees Ora Wildermuth, General Clay was impressed with Wells and wanted him to return to Germany to “participate in the formulation of internal policy in Germany concerning educational and cultural affairs.” The Jeffersonville Evening News reported that “the War Department has offered Dr. Wells, now aboard the Queen Elizabeth en route from Europe, a position on the staff of Gen. Lucius D. Clay, U. S. Military Governor of occupied Germany.”

On October 17, 1947, the IU board of trustees approved Wells’ appointment to the mission in Germany but only for a period of six months. Wells accepted the board’s decision on October 18, 1947 and agreed to embark on the mission. A governing Administrative Committee was created to take on Wells’ duties while he was in Germany. The Indianapolis News also noted Wells’ new appointment, saying “the board granted the leave provided Dr. Wells wished to accept the invitation of Gen. Lucius D. Clay, United States military governor. Dr. Wells indicated he would accept the post.”

Wells left for Germany on November 13, 1947, as indicated by the board of trustee minutes and formally accepted his post on November 23. His official title, according to the Indianapolis News, was “special adviser on cultural affairs to Gen. Lucius D. Clay, American military governor.” He would stay in Germany until May 27, 1948, only coming home twice for “necessary visits.”

Wells reflects on his experiences in Germany in a chapter in his memoir, Being Lucky. On his temporary residence, Wells wrote that “the people were sullen, disappointed, dispirited. Germany was a beaten nation.” His position coincided with three other advisors who constituted an “informal cabinet that reported directly to Clay in the Berlin headquarters.” Knowing that his appointment would be short, Wells spent the bulk of his time developing a plan for a permanent cultural advisor. His overall philosophy was to work directly with the Germans but not dictate exact policy. As Wells stated, “my point of view was that the Germans had to be responsible for their own reforms and that the best we could do was to aid the reform by suggestion and persuasion rather than by order and decree.”

His first action was to create the Education and Cultural Affairs Division (ECAD), a streamlined, unitary body that would develop policy, which until then had been decentralized and disorganized. His second task was an “attempt to create an agency in the United States to serve as a cultural liaison between the American people and the new Education and Cultural Affairs Division,” as he wrote in Being Lucky. Third, Wells worked with other divisions with the military government to supplement the cultural “reorientation work” done by the ECAD. Lastly, recruitment of personnel to the ECAD for “key positions” in the ECAD and its American counterpart.

After consulting with students as well as American journalist Kendall Floss, Wells also advised General Clay on the creation of a “free university of Berlin, free in the sense that students might have the freedom to study that a true university accords” that would be run with American support. This would eventually be developed as the Free University in Berlin, an educational counterweight to the Soviet-run university in East Berlin that “insist[ed] on a Marxist orientation for all scholarship.”

Regarding the Soviets, Wells and colleague Peter Fraenkel were arrested by “Soviet occupation authorities” in their controlled sector on January 12, 1948. They were held for three hours before being released to the United States Army police, the Indianapolis Star reported on January 13, 1948. Wells recounted the intense encounter in his memoirs:

We asked repeatedly why we were being held—as we sat in the car, while we were guarded in a building to which we were led, and after we had been taken to headquarters by a young Russian captain. The soldier accused us of driving round and round Potsdamer Platz taking pictures in a manner unfriendly to the Soviet Union. Though it was evident that the charge against us was fabricated because we had no camera, it was two hours before we were released into the custody of an American Military Police Captain. We were never in real danger, I suppose, but the detention was discomfiting and unpleasant.

While sources suggest a time discrepancy in how long they were held, the action by the Soviets was deemed so problematic by American authorities that they expected an apology, which they eventually received. As Wells remarked later, “although I was not the only staff member of the American military government ever arrested up to that time, the subsequent apology from the Russians was certainly a rarity.”

By February 1948, much of what Wells was required to implement had been completed and he was looking to finally return home to the United States, according to the Indianapolis Star. His father, Granville Wells, was also in poor health, which required Herman Wells to briefly return to the US for assistance. Unfortunately for Wells, his father died shortly after he resumed his post in Berlin. May 1948 finally saw the completion of Wells’ duties and returned home for good on June 8, 1948. Wells thanked the board of trustees for providing him with the leave to complete his assignment as well as for “kindnesses shown in connection with the recent death of his father.” As for his contributions, Wells received kind congratulations from General Clay, who wrote that his “contribution was of high order and, even more important, of lasting effect.”

In 1960, “in recognition of services in reorganization of the educational and cultural life of West Germany after World War II,” Herman B Wells received the Commanders Cross of the Order of Merit, West Germany, according to the trustee minutes.

Therefore, it is accurate to state, “after WWII, Wells served as educational advisor to General Lucius Clay in occupied Germany.”

[11] “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” April 18, 1952; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 13, 1952; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” September 29, 1953; “Minutes of the Board of Trustees of Indiana University,” June 10-13, 1955; “Wells Will Go to Frisco Session,” Indianapolis News, April 23, 1945, 7, Newspapers.com; “Herman B Wells at Parley in Interest in Education,” Indianapolis Star, April 30, 1945, 13, Newspapers.com; “Wells Predicts Frisco Success,” Indianapolis News, May 18, 1945, 23, Newspapers.com; “Wells to Attend UN Unit Session in Paris,” Indianapolis News, July 28, 1950, 2, Newspapers.com; “I.U. President Leaves for Paris UN Meeting,” July 29, 1950, 14, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “I.U. Prexy Named to UNESCO Body,” Indianapolis Star, June 27, 1951, 18, Newspapers.com; “Dr. Wells Appointed,” Valparaiso Vidette Messenger, June 27, 1951, 6, Newspaper Archive, Submitted by Applicant; “2d Term on UNESCO,” Indianapolis News, January 19, 1953, 7, Newspapers.com; “Wells Likely U.N. Delegate,” Indianapolis News, July 26, 1957, 21, Newspapers.com; “Endorse Wells,” Greencastle Daily Banner, July 27, 1957, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Wells is Delegate,” Greencastle Daily Banner, September 12, 1957, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Six Take Oath as U.N. Members,” Greencastle Daily Banner, September 13, 1957, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “I.U. Prexy Finds Jobs with U.N. a Busy One,” Indianapolis Star, September 22, 1957, 29, Newspapers.com; “Wells Asks Satellite ‘Controls,” Indianapolis Star, October 13, 1957, 1, 8, Newspapers.com; “Wells Outlines Race Problems to U.N.,” Indianapolis Star, November 1, 1957, 2, Newspapers.com; “Sputnik Victory is Brainwash, Dr. Wells Avers,” Indianapolis News, November 11, 1957, 22, Newspapers.com; “Wells to Report Work at U.N.,” Indianapolis News, January 27, 1958, 10, Newspapers.com; “State Educators Join Protest Against UNESCO Israel Ban,” Jewish Post, January 24, 1975, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; Wells, Being Lucky, 310-311, 320-339, 381-384, 450-456.

Herman B Wells’ involvement with the United Nations begins during WWII, when he served as a delegate to an international conference on November 10, 1943 to organize the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration, or UNRRA. Two years later, on April 23, 1945, Wells announced via the Indianapolis News that Secretary of State Edward R. Stettinius appointed him as a consultant representing the American Council on Education at the United Nations conference in San Francisco. During this conference, Wells’ stressed the importance of international education efforts to secure peace. “It is our belief,” he was quoted as saying in the Indianapolis Star, “that much can be accomplished toward maintaining world peace through international education.” That conference also culminated in the drafting of the UN charter, which Wells’ believed would “provide for the machinery by which the United Nations can win the final victory against war.”

In 1946, while on assignment in Germany he met with Julian Huxley, the biologist who served as the director-general of the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization, or UNESCO. As Wells’ reflected in Being Lucky, “We felt it desirable to have UNESCO’s understanding of what we were attempting to do in Germany and to secure its cooperation if possible. I had a satisfactory visit with Huxley about our problems and received his pledge of cooperation.”

From 1951-1955, Wells served on the US national commission of UNESCO, again as a representative for the American Council on Education. His pending appointment to the body was announced in the June 27, 1951 issue of the Indianapolis Star and Wells announced his acceptance of the position on April 18, 1952 to the IU board of trustees. He originally accepted the chairmanship on this body but chose to serve as a member, declining the chairmanship in the July 13, 1952 meeting of the board of trustees. Wells was reappointed to the national committee on January 19, 1953, as noted by the Indianapolis News. The minutes also note that, as a member of the national committee, Wells’ advised on a report presented to President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953, assuring the new commander-in-chief that UNESCO was “complimentary in nature” to U.S. interests and lacked any “subversive or anti-religious activity.”

As Well’s described in his memoir, “UNESCO’s program was to be carried out under seven broad headings: education, natural sciences, social sciences, cultural activities, exchange of persons, mass communications, and relief services.” Due to his experiences with General Clay in Germany, Wells’ advised UNESCO on establishing the country’s commission from 1949-50, before his formal appointment. This led to the creation of the International Institute for Education in Gauting, near Munich. Wells’ then served as a board member for the institute from 1951-1957. In this capacity, Wells attended governing board meetings for the institute in 1955, as indicated by the trustee minutes.

In the summer of 1957, at the height of the Cold War, Secretary of State John Foster Dulles asked Wells if he would like to attend the 12th session of the United Nations’ General Assembly as a member of the American delegation. Wells recalled, “I found the idea exciting, but I told him that I would have to consult with the Indiana University Board of Trustees. The trustees generously granted me permission to undertake this assignment, so from early September until nearly the end of December I served as a member of the U.S. delegation.” His membership was also endorsed by Indiana Senators Homer F. Capehart and William E. Jenner. Another Indiana native, former actor Irene Dunn, was also nominated for the position and accepted, as mentioned in the Indianapolis News. Wells took the oath of office on September 12, 1957, the Greencastle Daily Banner wrote, along with Dunne and AFL-CIO President George Meany. The delegation was led by Henry Cabot Lodge, the United States ambassador and the permanent representative to the United Nations.

In an interview with the Indianapolis Star, Wells shared how demanding the job was, saying “we’re going to be working here until 10 p.m. every night, with very few evenings off for plays and socializing. From what I’ve seen thus far of this job, I wouldn’t recommend it as a way to see New York.” However, he was enthusiastic about the work, noting “the United Nations is unquestionably the world’s greatest forum. Perhaps the greatest the world has ever had. I think it serves us a country, and has had frequent success in preserving the peace of the world.”

Wells routinely gave speeches on a variety of subjects during his time as a delegate. On October 12, 1957, Wells spoke on the “potential danger created by our space missile and satellites, [which] necessitates their international control,” the Star reported. However, Wells used the speech to also discuss the long-term goal of disarmament, which he believed was “the most significant problem facing the United Nations this year—a problem which affects every American and which is just as important here in Indiana as it is at the U.N. in New York.”

Two weeks later, on October 31, Wells spoke to delegates on the issue of race relations, both in the United States and abroad. Mentioning his home country, Wells said that “enormous progress’ had been made in gaining equality for all races in the United States since the Civil War” but much was left to be done, as indicated by the Star. He indirectly mentioned the U.S. Supreme Court decision of Brown v Board of Education, the desegregated public schools in the U.S., through approving of President Eisenhower’s decision to send the National Guard to Arkansas to support the integrating students at Little Rock school. He also criticized the apartheid government of South Africa, who had boycotted the assembly after the U.N. opened a debate about the regime.

In one of his last interviews as a U.N. delegate, Herman Wells scoffed at the Soviet Union’s launch of its space satellite, Sputnik, earlier that year. “I’ve become bored with their sputniks,” quipped Wells to the Indianapolis News. He said that the United States would not be far from behind and that Americans should stay vigilant against the USSR’s “cynical” propaganda efforts.

After his work with the American delegation, Wells stayed involved with the United Nations, working with its Secretary-General Dag Hammarskjöld on the Committee of Experts on the Review of the Activities and Organization of the Secretariat from May 17, 1960-February 1961.