Location: SR 250 and Allensville Rd., northwest corner, Allensville (Switzerland County, Indiana) 47043

Installed 2018 Indiana Historical Bureau and Switzerland County Junior Historical Society

ID#: 78.2018.1

This marker replaces the Birthplace John Shaw Billings marker (78.1966.1) installed in 1966.

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn about Billings's Civil War experience, medical library work, and design of Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn about Billings's Civil War experience, medical library work, and design of Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Text

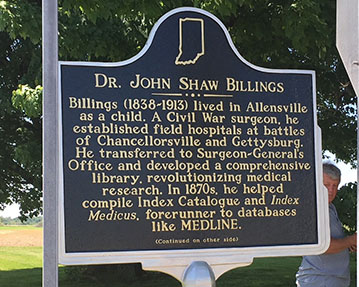

Side One:

Billings (1838-1913) lived in Allensville as a child. A Civil War surgeon, he established field hospitals at battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. He transferred to Surgeon-General’s Office and developed a comprehensive library, revolutionizing medical research. In 1870s, he helped compile Index Catalogue and Index Medicus, forerunner to databases like MEDLINE.

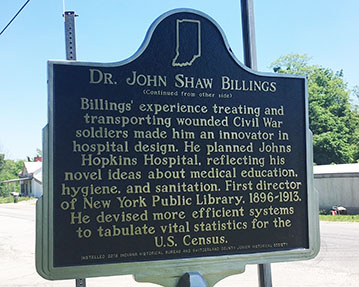

Side Two:

Billings’ experience treating and transporting wounded Civil War soldiers made him an innovator in hospital design. He planned Johns Hopkins Hospital, reflecting his novel ideas about medical education, hygiene, and sanitation. First director of New York Public Library, 1896-1913. He devised more efficient systems to tabulate vital statistics for the U.S. Census.

Annotated Text

Billings (1838-1913) lived in Allensville as a child.[1] A Civil War surgeon, he established field hospitals at battles of Chancellorsville and Gettysburg.[2] He transferred to Surgeon-General’s Office and developed a comprehensive library, revolutionizing medical research.[3] In 1870s, he helped compile Index Catalogue and Index Medicus, forerunner to databases like MEDLINE.[4]

Billings’ experience treating and transporting wounded Civil War soldiers made him an innovator in hospital design.[5] He planned Johns Hopkins Hospital, reflecting his novel ideas about medical education, hygiene, and sanitation.[6] First director of New York Public Library, 1896-1913.[7] He devised more efficient systems to tabulate vital statistics for the U.S. Census.[8]

[1] John Shaw Billings, “An Autobiographical Fragment 1905: A Facsimile Copy of the Original Manuscript (1965),” 1, accessed Archive.org; “John Shaw Billings,” accessed Find A Grave; “1850 United States Federal Census About John S Billings,” accessed Ancestry.com; Thomas Jefferson Griffith, “High Points in the Life of Dr. John Shaw Billings,” Indiana Magazine of History 30, no. 3 (September 1934): 325-328, accessed Indiana Magazine of History Online, Indiana University ScholarWorks; A. McGehee Harvey and Susan L. Abrams, “John Shaw Billings: Unsung Hero of Medicine at Johns Hopkins,” Maryland Historical Magazine 84, no. 2 (Summer 1989): 121; Carleton B. Chapman, Order Out of Chaos: John Shaw Billings and America’s Coming of Age (Boston: The Boston Medical Library, 1994), 10-11, Chapter 3; Fielding H. Garrison, John Shaw Billings: A Memoir (New York: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, The Knickerbocker Press, 1915), 15-16, accessed Google Books. Garrison quotes Billings from an 1888 newspaper article in the Cincinnati Lancet-Clinic. Garrison’s book is authoritative and contains several facsimiles of Billings’ letters and journals. However, its title is misleading, as the book is not a memoir written by Billings himself, but rather a detailed account of his life written by a colleague.

Billings was born April 12, 1838. Secondary sources note that he was born in Allensville, Indiana, but primary sources could not be located to confirm this. In 1841, the family moved to various parts of the East Coast-including New York, Connecticut, and Rhode Island- before reportedly returning to Allensville around 1848. At the age of fourteen, Billings passed the entrance exam for Miami University at Oxford, Ohio, earning his B.A., and in 1858 entered the Medical College of Ohio at Cincinnati. He graduated with his medical degree in 1860, after completing his thesis “The Surgical Treatment of Epilepsy.” Billings’ struggle to obtain sources for his thesis informed his bibliographical work and the composition of the Index Catalogue, expounded upon later in the review (See footnote 3 and 4).

[2] J.S. Billings, “Extract from a Narrative of his Services in the Medical Staff,” in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 1, pt. 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870), 135-136, accessed Archive.org; “The Doctors of America,” Logansport Journal, October 21, 1888, 2, accessed Newspaper Archive; “An Autobiographical Fragment 1905,” [2]; Memorial Meeting in Honor of the Late Dr. John Shaw Billings, April 25, 1913 (New York: The New York Public Library, 1913): 6-9, accessed Google Books; John Shaw Billings: A Memoir, 61-62, 64-65; “High Points,” 326-327; “John Shaw Billings: Unsung Hero of Medicine at Johns Hopkins.”

The American Civil War commenced shortly after Billings graduated, providing him with opportunities to apply his medical knowledge. In 1861, he traveled to Washington, D.C. and became a contract-surgeon with the military. He was then appointed assistant surgeon in the U.S. Army, working at Union Hospital in Georgetown. While there, his “extraordinary manual skill and boldness in dealing with difficult cases attracted the attention of the surgeon-general” and he was put in charge of Cliffburne Hospital near Georgetown. He was then assigned to work with the 11th Infantry, Fifth Corps, establishing a hospital for soldiers in anticipation of the Chancellorsville fight. During the Battle of Chancellorsville, Billings experienced the “terrible problem of moving again and again the wounded of a retreating army,” due to the proximity of the fighting to the field hospital. He was later assigned to the Second Division of the Fifth Army Corps, establishing a hospital at Gettysburg. Billings wrote to his wife about the Battle of Gettysburg, lamenting:

I am utterly exhausted, mentally and physically. I have been operating night and day, and am still hard at work. I have been left in charge of 700 wounded, and have got my hands full. Our division lost terribly, over 30 per cent were killed and wounded. I had my left ear just touched with a ball . . . I am covered with blood, and am tired out almost completely, and can only say that I could lie down and sleep for sixteen hours without stopping. I have been operating all day long, and have got the chief part of the work done in a satisfactory manner.

Billings also treated soldiers during the Battles of the Wilderness, Cold Harbor and Petersburg. Billings took a brief respite from active duty due to “nervous tension and physical exhaustion,” returning to the field March 1864. He later transferred to the Washington, D.C. office of the medical director of the Army of the Potomac, where he edited field reports that became the comprehensive The Medical and Surgical History of the War. He also built up the library of the Surgeon-General’s Office, where he remained until retirement in 1895 (see footnote 3 and 4).

[3] “Secretary’s Report [Kaaterskill Conference],” Bulletin of the American Library Association 7, no. 4, accessed JSTOR; Memorial Meeting in Honor of the Late Dr. John Shaw Billings, 6-9; John Shaw Billings: A Memoir, 15-16; “John Shaw Billings, 1838-1913,” The British Medical Journal 1, no. 4031 (April 9, 1938): 796, accessed JSTOR; “John Shaw Billings: Unsung Hero of Medicine at Johns Hopkins,” 125; “A Brief History of NLM,” last modified December 11, 2015, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

As the war concluded, Civil War hospitals submitted approximately $85,000 in savings to the Surgeon-General’s Office, which was allotted to Billings to cultivate the Office’s medical library (which later became the National Library of Medicine). He recalled the “intense drudgery” of his thesis research, which required him to visit libraries in Cincinnati and Philadelphia, a process that involved intensive labor and time. This experience prompted him to establish a complete medical library for physicians and an accompanying index that “would spare medical teachers and writers the drudgery of consulting ten thousand or more different indexes or of turning over the leaves of as many volumes to find the dozen or so references of which they might be in search.” According to the U.S. National Library of Medicine, Billings built up the collection by writing to editors, librarians, physicians, and State Department officials asking for donations of books.

[4] J.S. Billings (Bvt. Lt. Col. and Surgeon) to General Joseph K. Barnes (Surgeon-General, U.S. Army), June 1, 1880, in Library of the Surgeon-General’s Office, Index-Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon-General’s Office, United States Army, Authors and Subjects, series 1, vol. 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1880): iii-v, accessed U.S. National Library of Medicine, Digital Collections; Memorial Meeting in Honor of the Late Dr. John Shaw Billings, 9; “Dr. Billings Selected: Named for Superintendent of the New York Public Library,” New York Times, January 9, 1896, 9, accessed ProQuest Historical Newspapers: The New York Times; “Meet to Do Honor to Late Dr. Billings,” New York Times, April 26, 1913, 8, accessed Historical Newspapers: The New York Times; Stephen J. Greenberg and Patricia E. Gallagher, “The Great Contribution: Index Medicus, Index-Catalogue, and IndexCat,” J Med Libr Assoc 97, no. 2 (April 2009): 108-109, 111, 113, accessed National Center for Biotechnology Information.

Billings began work on the index in 1873 and, with the assistance of Dr. Robert Fletcher, published the first volume of the Surgeon General’s Medical Index Catalogue in 1880. The Index Catalogue served as an invaluable reference tool for medical professionals. According to the New York Times, Sir William Osler, Oxford University medical professor and friend of Billings, contended that “no undertaking in bibliography of the same magnitude dealing with a special subject had ever been issued, and its extraordinary value was at once appreciated all over the world.” Dr. Osler elaborated that the Index Catalogue was an “exhaustive index of all medical literature, in all its departments and subjects, dealing with all its authors from the most ancient to the most recent times.” As new medical materials were published it became a struggle to keep the Catalogue current, so Billings devised the Index Medicus, a monthly supplement that was “far narrower in scope [than the Catalogue], focusing on new articles from selected journals, selected new books, and theses.” Dr. Stephen J. Greenberg and Patricia E. Gallagher succinctly describe the differences between the Catalogue and Medicus, stating that the “Index Medicus was the newsletter of the medical publishing world, while the Index-Catalogue was the research guide to a particular medical library that would grow to become the world’s largest.”

The Index Medicus was the forerunner to the digital medical databases MEDLINE and PubMed. Greenberg and Gallagher summarized Billings’ bibliographical contributions, contending that “with only ink and index cards, they [Billings and Fletcher] tamed an enormous and complex technical literature in virtually every written language on the planet” and that the indices “paved the way for the great databases that now are the primary underpinnings for the medical research of the future.” An abundance of sources demonstrate how prolific Billings’ Index Catalogue was. The New York Times asserted “His great work on which his fame as a bibliographer rests is the ‘Index-Catalogue of the Library of the Surgeon General’s Office . . . This catalogue is said to be the best and most complete of its kind in the world.”

[5] J.S. Billings, “Report on the Treatment of Diseases and Injuries in the Army of the Potomac during 1864,” in The Medical and Surgical History of the War of the Rebellion, vol. 1, pt. 1 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870): 199, accessed Archive.org; John S. Billings, M.D., Address as Chairman of the Section, “The Relations of Hospitals to Public Health,” Section 1: General Session in Hospitals, Dispensaries and Nursing: Papers and Discussions in the International Congress of Charities, Correction and Philanthropy, Section III, Chicago, June 12th to 17th, 1893, eds. John S. Billings, M.D. and Henry M. Hurd, M.D. (Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins Press, 1894), 4, accessed Google Books; Memorial Meeting in Honor of the Late Dr. John Shaw Billings, 6-11; “John Shaw Billings: Unsung Hero of Medicine at Johns Hopkins,” 121.

Billings’ accomplishments extended beyond medical bibliography and into hospital planning, as he became a “leading authority and acquired international reputation” in the construction and organization of hospitals. Billings’ interest in hospital design and management began during the Civil War, where he experienced the struggle of treating and transporting large numbers of wounded soldiers. Dr. Welch asserted that Billings’ interest “can be traced to his experiences as a surgeon in our Civil war, in the course of which there was developed a new style of building hospitals.”

[6] John Shaw Billings, A Report on Barracks and Hospitals with Descriptions of Military Posts, Circular No. 4 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870), accessed Google Books; John Shaw Billings, ed., A Report on the Hygiene of the United States Army, with Descriptions of Military Posts, Circular No. 8 (Washington: Government Printing Office, 1870), accessed Google Books; “John Shaw Billings,” Science 37, no. 953, 512, accessed Archive.org; John S. Billings (Bvt. Lt.-Col. And Asst. Surg., U.S.A.), ”Hospital Construction and Organization,” in Hospital Plans: Five Essays Relating to the Construction, Organization & Management of Hospitals, Contributed by their Authors For the Use of the Johns Hopkins Hospital of Baltimore (New York: William Wood & Co., 1875), 15, accessed Google Books; John M. Woodworth and John S. Billings, Cholera Epidemic of 1873 in the United States (Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office, 1875), accessed U.S. National Library of Medicine, Digital Collections; Francis T. King (President of Board of Trustees), “Letter Addressed to the Authors of the Essays,” in Hospital Plans: Five Essays Relating to the Construction, Organization & Management of Hospitals, Contributed by their Authors For the Use of the Johns Hopkins Hospital of Baltimore (New York: William Wood & Co., 1875), accessed Google Books; John S. Billings, “The Plans and Purposes of the Johns Hopkins Hospital: An Address Delivered at the Opening of the Hospital, May 7, 1889,” The Medical News, May 11, 1889, 9-10, 12, 17, accessed Google Books; “The Relations of Hospitals to Public Health,” 4; “An Astronomical Founder,” The (Washington D.C.) Evening Star, May 26, 1894, n.p., accessed Chronicling America; John S. Billings, M.D. (Director of the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania) and Henry M. Hurd, M.D. (Superintendent of the Johns Hopkins Hospital), Suggestions to Hospital and Asylum Visitors (Philadelphia: J. B. Lippincott Company, 1895): 19, accessed Google Books; Memorial Meeting in Honor of the Late Dr. John Shaw Billings, 11-12; “High Points,” 328; “John Shaw Billings: Unsung Hero of Medicine at Johns Hopkins,” 120, 123, 127.

Billings’ “novel approach” to hospital administration appealed to the trustees of Johns Hopkins’ fund, who, after inviting five medical professionals to submit plans for the establishment of a hospital, selected Billings’ design in 1876. Billings’ revolutionary ideas about medical education and treatment are apparent in his essay to the trustees, and reflect his belief that a hospital should not only treat patients, but educate medical professionals. In his proposal, Billings emphasized the importance of the hospital to the university, the publication of “original investigations,” and raising the standards of medical education, so that a diploma ensured the physician could “learn to think and investigate for himself.” He also contended that “by ventilation and through scientific cleanliness this danger may be almost wholly averted, and this is the theory of good hospital management as usually taught.”

These principles were incorporated into Johns Hopkins Hospital, opened in 1889, and designed to be a “great laboratory for teaching the practical applications of the laws of hygiene to heating, ventilation, house drainage, and other sanitary matters” and “to increase our knowledge of the causes, symptoms, results, and treatment of disease.” The hospital included a training school for nurses, a pathological laboratory for experimental research, and connected to a building with a teaching amphitheatre. Dr. Welch summarized Billings’ colossal impact on hospital planning, stating that Johns Hopkins Hospital:

marked a new era in hospital construction . . . When one considers the influence of this hospital upon the construction of other hospitals and the valuable contributions made by Dr. Billings to the solution of various hospital problems, when one also regards the uses which have been made of this hospital in the care and treatment of the sick, in the training of students and physicians and the promotion of knowledge, it is evident that Dr. Billings’ services in the field we are now considering were of large and enduring significance.

In addition to establishing the Johns Hopkins Hospital, Billings served as director of the University of Pennsylvania Hospital and taught there as a professor of hygiene. An early advocate of preventative medicine, he taught about the importance of sanitation and hygiene in hospitals, designing them to minimize the spread of disease. In his 1893 “The Relations of Hospitals to Public Health,” Billings asserted that the “importance of hospitals for certain forms of contagious and infectious disease, as a means of preventing the spread of such diseases, would appear to be almost self-evident, yet very few cities in this country are provided with them.” He emphasized the prevention of illness rather than solely its isolation, advocating for the move from “pest houses,” that secluded ill patients, to better medical facilities. Billings eliminated corners from the Johns Hopkins Hospital to prevent the buildup of dust and disease and designed it so that visitors and staff had to go outside to travel from one ward to another, ensuring that “foul air, in any forms, cannot spread from one building to another.” According to A. McGehee Harvey and Susan L. Abrams, Billings’ emphasis on prevention through hospital design “helped to stimulate the revolution in medical practice” in the late 1880s.

An 1894 article in The (Washington, D.C.) Evening Star proclaimed Billings the “foremost authority in this country in municipal hygiene and medical literature.” In addition to advocating for preventative and hygienic measures in hospitals, Billings tried to implement prevention in the public sphere. He spearheaded the “national public hygiene movement,” joining the American Public Health Association in 1872 (becoming president in 1880) to “replace a system of sanitation based on individual opinion and hypothesis with one based on science.” He also conducted major surveys and statistics to improve sanitary efforts that could impede the spread of disease.

In an 1893 address, Billings also emphasized the importance of disease prevention in the military, stating:

As it is to the interest of a medical officer of the army and navy to prevent, as far as possible, the occurrence of disease among the command to which he is assigned, in order that he may have as little as possible to do in the way of treatment, so it is supposed that these other medical officials will be active, zealous and efficient agents in prescribing and enforcing state and municipal sanitation.

Harvey and Abrams assert that when Billings retired from the Army in 1895 he was “regarded as the leading authority on public hygiene in the country, and his services and advice were in demand everywhere.” Billings attempted this sanitary reform by conducting and reporting on systematic sanitary surveys of the U.S., including for the yellow fever. Each report represented “pioneer hygienic work, far ahead of its time, undertaken in a day when there were no uniform quarantine regulations in the United States.”

[7] The Buffalo Commercial, January 10, 1896, 6, accessed Newspapers.com; “John Shaw Billings,” Science, 512; “Meet To Do Honor To Late Dr. Billings,” New York Times, 8; Order Out of Chaos, 302-316, Chapter 15; “John Shaw Billings Records, 1885-1915,” The New York Public Library, Archives and Manuscripts, accessed nypl.org.

In 1896 Billings served as the first director of the New York Public Library (serving until his death in 1913), expanding its collections “without parallel.” According to the library’s description of John Shaw Billings’s records, he “helped create NYPL by combining the Astor and Lenox Libraries into a public research library and building a branch library system for three of the boroughs of New York City (Manhattan, Staten Island and the Bronx).” Additionally, he “planned and oversaw the construction of the NYPL Central Building which was opened to the public in 1911.” Industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie solicited his help in establishing a system of branch libraries in New York City and referred to Billings on various educational matters. Additionally, Billings convinced Carnegie to donate millions of dollars to public libraries throughout the United States.

[8] “Hollerith Cards,” excerpted from “On Some Forms of Tables of Vital Statistics, with Special Reference to the Needs of the Health Department of a City,” Public Health Papers and Reports, American Public Health Association 13 (1887), 204-205 in Medical Library Association, Selected Papers of John Shaw Billings (Baltimore: Waverly Press, 1965), accessed U.S.National Library of Medicine; (London) Times, July 22, 1915 in Biographical Memoir of John Shaw Billings, 400; National Library of Medicine, John Shaw Billings Centennial (U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, National Library of Medicine, ca. 1965): [4-5], accessed U.S. National Library of Medicine; Order Out of Chaos, 239.

Billings worked with the U.S. Census from 1880 to 1910 to develop vital statistics. He sought to record census data on cards using a hole punch system, which would allow the data to be counted mechanically. In an 1887 publication, Billings recommended that for cities with a population of 200,000 or more and states with a sufficient registration system, “each individual death be recorded, as fast as reported, upon cards by punching holes.” He noted that in 1880 he was convinced of the efficiency of mechanical data collection and “advised Mr. Hollerith, who was then engaged on census work, to take the matter up and devise such a machine as is needed for counting various combinations of large numbers of data.” Herman Hollerith applied Billings’ concept, devising “‘electrical counting and integrating machines’” employed by the U.S. Census. According to a 1915 London Times article, before Billings revised the collection of vital statistics “they were worse than worthless” and that “from a state of chaos he brought the vital statistics of the United States to their present satisfactory condition.”

For Further Information

Dr. Fielding H. Garrison provides access to some of Billings’ letters and journal entries in his 1915 John Shaw Billings: A Memoir.

For a comprehensive scholarly analysis of Billings’ contributions, see Carleton B. Chapman’s 1994 Order Out of Chaos: John Shaw Billings and America’s Coming of Age.

The Alan Mason Chesney Medical Archives of the Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions: “The John Shaw Billings Collection consists mostly of historical articles and correspondence about Billings and his role in developing the Johns Hopkins Hospital and School of Medicine. Material by Billings includes one folder of correspondence (1871-1902) and some of Billings' articles on hospital construction and medical education.”

Milton S. Eisenhower Library of the Johns Hopkins University: contains Billings’ correspondence, located in the Daniel Coit Gilman papers.

New York Public Library Archives and Manuscripts: contains the John Shaw Billings Papers, 1862-1913, consisting of documents related to Billings’ work with the U.S. Army Medical Department, Johns Hopkins Hospital, the 10th and 11th census, New York Public Library and the Carnegie Institute. The collection also contains family correspondence, diaries and scrapbooks related to his experiences in the Civil War.

U.S. National Library of Medicine, John Shaw Billings Papers, 1841-1975: consists of “Billings' correspondence during his time as head of the Library of the Surgeon General (1868-1895). Also includes some biographical information, a collection of Billings' reprints, speech texts, scrapbooks, and clippings.”

Keywords

Science, Medicine, & Invention; Education & Library; Buildings & Architecture