Location: Corner of N. Elmer St. and Keller St., near 1702 N. Elmer St., South Bend (St. Joseph County, IN)

Installed 2017 Indiana Historical Bureau, City of South Bend, and Far Northwest Neighborhood Association

ID#: 71.2017.2

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog or

Visit the Indiana History Blog or  listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about fighting housing discrimination in South Bend.

listen to the Talking Hoosier History podcast to learn more about fighting housing discrimination in South Bend.

Text

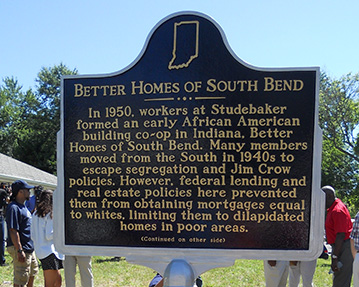

Side One

In 1950, workers at Studebaker formed an early African American building co-op in Indiana, Better Homes of South Bend. Many members moved from the South in 1940s to escape segregation and Jim Crow policies. However, federal lending and real estate policies here prevented them from obtaining mortgages equal to whites, limiting members to dilapidated homes in poor areas.

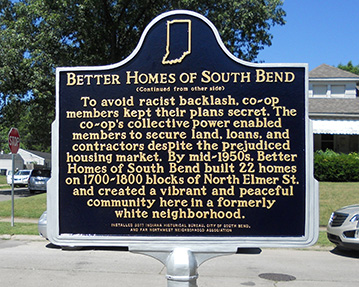

Side Two

To avoid racist backlash, co-op members kept their plans secret. The co-op’s collective power enabled members to secure land, loans, and contractors despite the prejudiced housing market. By mid 1950s, Better Homes of South Bend built 22 homes on 1700-1800 blocks of North Elmer St. and created a vibrant and peaceful community here in a formerly all white neighborhood.

Annotated Text

Side One

In 1950, workers at Studebaker formed an early African American building co-op in Indiana, Better Homes of South Bend.[1] Many members moved from the South in 1940s to escape segregation and Jim Crow policies.[2] However, federal lending and real estate policies here prevented them from obtaining mortgages equal to whites,[3] limiting members to dilapidated homes in poor areas.[4]

Side Two

To avoid racist backlash, co-op members kept their plans secret.[5] The co-op’s collective power enabled members to secure land, loans, and contractors despite the prejudiced housing market.[6] By mid 1950s, Better Homes of South Bend built 22 homes on 1700-1800 blocks of North Elmer St.[7] and created a vibrant and peaceful community here in a formerly all white neighborhood.[8]

[1] “People’s Co-Op Opens Store on N. West Street,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 1, 1944, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1949), 133, 383, 722; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1950), 782; Better Homes of South Bend. Meeting Minutes, May 21, 1950, Leroy Cobb Papers, personal collection, submitted by applicant; Better Homes of South Bend, Meeting Minutes, September 29, 1950, Leroy Cobb Papers; Advertisement: Colored Co-Op, Indianapolis Recorder, November 18, 1950, 14 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Better Homes of South Bend, Meeting Minutes, March 10, 1951 Leroy Cobb Papers; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1951-1952), 28, 31, 32, 37, 83, 123, 138, 155, 157, 248, 261, 361, 373, 595, 780, 781, 828, 832, 854, 860; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1953), 123; Document Name DB0524-0571 (Better Homes of South Bend to William H Wilson Jr.), February 11, 1954, St. Joseph County Recorder, South Bend, IN, accessed Land Records Search. Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1956), 644, 706, 782; “The Avenoo: No. 28 in a Series,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 21, 1957, 12, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), 77-78; Leroy Cobb and Margaret Cobb, “Leroy and Margaret Cobb on Better Homes pt. 1,” interview by Adrienne Collier and David Healey, December 11, 2001, transcript, Oral History Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, South Bend, Indiana, 3-5, accessed Michiana Memory; Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Collective Courage: A History of African American Cooperative Economic Thought and Practice (University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2014), 133, 139; Gabrielle Robinson, Better Homes of South Bend: An American Story of Courage (Charleston, SC: The History Press, 2015), 76; Email correspondence from Gabrielle Robinson, marker applicant to IHB Staff, April 27, 2017.

The first page of meeting minutes for Better Homes of South Bend, described as a “non-profit organization” is dated May 21, 1950. The group formed to find “a beautiful site for building,” homes for members. Member Leroy Cobb explained, “In 1950, in the spring, a group of us blacks formed Better Homes of South Bend, Incorporated.” He noted the purpose of the organization was to “secure homes, better homes, of South Bend…We had these homes built, because at the time we encountered so much problem about having a home built, blacks, and financed.”

At a meeting on September 29, 1950, all current male members were listed in the minutes, when the group assigned lot numbers to each family: Wade Fuller, Marcus Cecil, Leroy Cobb, Bland Jackson, Clint Taylor, Gus Watkins, Robert Taylor, Earl Thompson, John Fleming, Arnold Allen, Robert Allen, Schuyler Braboy, Orbry Chambers, Joseph Roberson, FD Coker, Bozzie Williams, Alfred Warfield, James Adams, WC Bingham, Eugene Northern, Sherman Paige, Willie Gillespie, Robert Graham, Donald Howell, Walter Hubbard, Herschell Collier. Several members ended up dropping out, including Schuyler Braboy, Joseph Roberson, Eugene Northern, Robert Graham, Donald Howell, and Herschell Collier. According to Gabrielle Robinson, Frank Anderson and Louis Stanford joined later. Deed records from the St. Joseph County Recorder indicate William H. Wilson Jr also received land from Better Homes of South Bend and his name appears in City Directories at 1825 N Elmer Street in 1954, when only 12 other Better Homes of South Bend families were listed as well. It is unclear if he was an original member. According Gabrielle Robinson, who contacted former member Leroy Cobb, “Wilson was not a part of that original group, but moved in very soon after.” Also, Wilson’s name never appears in the Better Homes of South Bend meeting minutes. Therefore, Wilson is not counted in the final 22 homes built. The 1956 Polk’s South Bend City Directory shows the last names of all members once all houses were built (see footnote 7).

Polk’s South Bend City Directory from 1949, 1950, 1951-1952, and 1953 indicate that eighteen of the twenty two final male members of Better Homes of South Bend were employed at Studebaker factory in South Bend. The 1951-1952 directory lists Leroy Cobb, Bland Jackson, Gus Watkins, Robert Allen, John Fleming, Walter Hubbard, James Adams, Robert Taylor, Wade Fuller, Arnold Allen, Frank Anderson, Willie Gillespie, Clint Taylor, Marcus Cecil, Albert Warfield, and Sherman Paige as Studebaker employees. Though not listed in the 1951 directory, Earl Thompson was described as a Studebaker employee in the 1949 directory. The last five members’ employment was listed as follows: John Stanford was listed as “jan Paris Dry Clng” in the 1950 city directory, Frederick D. Coker “collr City Water Works,” Bozzie Williams “lab Christman constn” and Orbry Chambers as “jan Tel Co.” in the 1953 city directory.

Spouses of the men were also members: Beutha Fuller, Lelar Cecil, Margaret Cobb, Rosa Jackson, Cleopatra Taylor, Josie Watkins, Louise Taylor, Viro Thompson, Millie Fleming, Lureatha Allen, Rose Allen, Ruth Chambers, Geraldine Coker, Lila Williams, Rose Warfield, Florence Adams, Katherine Bingham, Ruby Paige, Marie Gillespie, Jeanetta Hubbard, Virgie Anderson, Daisy Stanford, and Katherine Wilson. All of the women could be identified as spouses of the above stated members in the city directories listed above, except for Viro Thompson, who is identified as a spouse in a 1956 South Bend City Directory. The only female members who had a listed occupation included Geraldine Coker, who was employed as a chairwoman, Ruby Paige, as an aide for St. Joseph Hospital, and Lureatha Allen as “fnshr Crystal Clns & Laundry.”

Meeting minutes from March 10, 1951 note that DeHart Hubbard, a race relations Federal Housing Administration (FHA) employee, visited the group to advise them on obtaining loans from FHA and told members that the group would “go down in History as the first co-op in Indiana to sponsor such a successful adventure.” Considering the secrecy with which this group operated (see footnote 5) it would be hard to prove Better Homes of South Bend was the first African American housing co-op in the state, however evidence shows it was likely an early successful example. Jessica Gordon Nembhard, a scholar of African American cooperatives, notes the first large African American housing cooperatives began in Harlem, New York in the late 1920s and several more had been established in the area in the 1930s. Emma Lou Thornbrough wrote that African American cooperatives in Indiana began in the 1930s, though few ever got beyond the planning stage and many survived only a short time. Many early African American cooperatives appear to have been markets and grocery stores, such as the Gary Consumer Trading Company, formed in 1932 in Gary, Indiana, or the Peoples Cooperative Association in Indianapolis, established 1944. In the 1930s, Dr. Benjamin Osbourne started the Homestead Project with the aims of building homes in Wayne Township in Indianapolis for low income workers, including African Americans, but the venture did not succeed after the Indianapolis Real Estate Board voiced opposition. The Indianapolis Recorder, Indiana’s most prominent African American newspaper at the time, was searched using the Hoosier State Chronicles database for evidence of other African American building and housing co-ops before Better Homes of South Bend. Only one, an apartment co-op, was found. According to the Indianapolis Recorder, M.W. Jones, Sr., formed the “first Negro co-op Apartments in the city and the state, the Lexington, 1116 N Capitol Ave, the Pasadena, 11th and Illinois Streets, and the Pierson in the 2400 block on Pierson Street.” Advertisements for Jones’s “Colored Co-Op” first appeared in the Indianapolis Recorder in the fall of 1950.

[2] All death certificates, birth certificates, marriage records, social security claims, and census records were accessed in Ancestry Library, unless otherwise noted. Sources are listed alphabetically by Better Homes of South Bend members’ last name.

Death Certificate for Florence Adams, October 5, 1971, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, Indiana Archives and Records Administration (IARA), Indianapolis, IN; Marriage License for Arnold Algion Allen and Lureatha Beryl Scott, September 12, 1931, 515, Elkhart County, IN, Indiana Marriages, 1810-2001 FamilySearch, 2013; 1940 US Federal Census, South Bend, St. Joseph County, Indiana, roll T627_1133, page 2B, line 68 (Robert Allen Jr); Marriage License for Frank Anderson and Virgie Lee McCullum, July 14, 1951, 506, Elkhart County, IN, Indiana, Marriages, 1810-2001, Salt Lake City, Utah, FamilySearch, 2013; Death Certificate for William C. Bingham, October 11, 2004, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Marriage License for Willie C. Bingham and Katherine Berens, September 9, 1947, 128, Madison County, TN, Tennessee State Marriages, 1780-2002, Microfilm, Tennessee State Library and Archives, Nashville, TN; Birth Certificate for Marcus Cecil Jr, May 25, 1924, Indiana State Board of Health, Birth Certificates, 1907-1940, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; 1940 US Federal Census, Sandusky, Alexander County, Illinois, roll T627_758, page 9B, lines 74-75 (Orbry and Ruth Chambers); Birth Certificate for Leroy Cobb, April 30, 1930, Indiana State Board of Health, Birth Certificates, 1907-1940, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Margaret Jean Cobb, March 7, 2007, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Frederick D. Coker, March 27, 1969, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificates for Geraldine Anita Coker, April 3, 1988, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Gabrielle Robinson, Better Homes of South Bend, 64; 1930 US Federal Census, Christian County, Kentucky, roll 740, page 7B, line 88 (John E Fleming); Millie Lois Driver, US Social Security Applications and Claims Index, 1936-2007, Provo, UT, USA; Death Certificate for Wade Fuller, July 24, 1987, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Beautha L. Fuller, February 26, 1993, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Jeanetta Hubbard, August 28, 2010, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Walter Theodric Hubbard Jr., February 26, 1989, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Record of Marriage for Michael Ray Jackson and Elizabeth Ann Bramlett, July 26, 1997, Book 269, Page 404, St. Joseph County, IN Indiana, Marriage Certificates, 1958-2005, Provo, UT; 1940 US Federal Census, South Bend, St. Joseph County, Indiana, roll T627_1133, page 14A, lines 13 (Sherman Paige); Death Certificate for Daisy Marie Stanford, December 7, 1998, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Daisy Marie Stanford, December 7, 1998, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for John Louis Stanford, March 9, 1997, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Louise Taylor, February 21, 1997, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; 1940 US Federal Census, Noxubee County, Mississippi, roll T627_2054, page 5B, lines 49 (Robert E Taylor); 1940 US Federal Census, Oakdale City, Allen County, Louisiana, roll T627_1379, page 23A, lines 10-11 (Clint and Cleopatra Taylor); Death Certificate for Earl W. Thompson Sr., April 1, 2006, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Viro Martha Thompson, June 26, 1996, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Albert Napoleon Warfield, August 12, 1976, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Rosie Lee Warfield, July 21, 1999, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificate for Josie Watkins, September 2, 2000, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; Death Certificates for Bozzie Williams, January 6, 2010, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN; 1940 US Federal Census, Dover, Craven County, North Carolina, roll T627_2894, page 1B, lines 59 (Lila B Oates); Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press, 2000), 34, 101-103; Sarah-Jane (Saje) Mathieu, “The African American Great Migration Reconsidered,” OAH Magazine of History Vol. 23 No. 4 (October 2009): 19-20; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1940), 27, 259; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1949), 28, 31, 32, 131, 133, 238, 251, 346, 358, 573, 722, 754, 759, 800, 803; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1950), 85, 706, 912. Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1951), 37, 276, 780.

Birth certificates, marriage certificates, death certificates, and US federal census records were used to verify many members lived in the South before coming to South Bend. Records indicated that twenty-eight of forty-four members previously lived in the Southern United States, including Arnold Allen, Lureatha (Scott) Allen, Robert Allen, Jr., Frank Anderson, Katherine (Berens) Bingham, Willie C. Bingham, Marcus Cecil, Ruth Chambers, John Fleming, Millie (Driver) Fleming, Wade Fuller, Walter T. Hubbard, Bland Jackson, Rosa Jackson, Sherman Paige, Daisy Stanford, Clint Taylor, Louise Taylor, Robert Taylor, Earl Thompson, Viro Thompson, Albert Warfield, Rose Warfield, Gus Watkins, Josie Watkins, Bozzie Williams, and Lila (Oates) Williams. Gabrielle Robbinson notes member Leroy Cobb recalled that Willie Gillespie, his best friend, had come from the South as well in her book Better Homes of South Bend. Twelve of the remaining sixteen members came from the North or West, including five from Indiana: Leroy and Margaret Cobb, Frederick and Geraldine Coker, and Daisy Stanford. Those that could not be identified with available records include Millie Fleming, James Adams, Ruby Paige, and Marie Gillespie. South Bend, Indiana city directories from 1940 and 1949 were compared to demonstrate many members, who were not originally from Indiana, arrived in the 1940s. Only two members’ names, James E Adams and Walter Hubbard (spouse names not present) were listed in the 1940 city directory. However, neither Adams nor Hubbard appeared in the 1939 directory. All members, except Frank Anderson, William and Katherine Bingham, Willie and Marie Gillespie, Clint and Cleopatra Taylor, and Bozzie and Lila Williams were present in the 1949 city directory. The Binghams and the Williams appeared first in 1950. Frank Adnerson, the Gillespies, and the Taylors first appeared in 1951.

Emma Lou Thornbrough describes the Great Migration in her book Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century as a movement of millions of African Americans from the South to Northern states, starting primarily during WWI and from WWII until 1970. She observes African Americans left the South in “hopes of better jobs, higher wages, improved standards of living” but also because they wanted to “escape oppressive racial systems of the South---that they envisioned a North where there was no racial segregation, but could enjoy full citizenship, and where their children could have educational opportunities equal to whites.” Sarah-Jane (Saje) Mathieu agrees, asserting that “racialized violence served as an unyielding push factor for African American migration” from the South to the North, in addition to “labor needs, food crisis, political persecution, urbanization, natural disaster, and of course free choice.” She further explains that during the Jim Crow Era (1877-1954), African Americans left the South to escape “rising racial terrorism,” brought on by white supremacist violence and state and local laws that enforced racial segregation in public spaces, resulting in inferior facilities, including schools, libraries, and public transportation for African Americans in the South.

[3] United States, Underwriting Manual: Underwriting Analysis Under Title II, Section 203 of the National Housing Act (Washington, DC: 1936), 228, 233, 284, accessed HathiTrust; “Security Maps for Analysis of Mortgage Lending Areas,” Federal Home Loan Bank Review vol. 2 no. 11 (August 1936): 389-391, accessed FRASER; U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Banking and Currency, Housing Amendments of 1949: Hearing Before the Committee on Banking and Currency, 81st Cong., 1st sess., 1949, 520, accessed HathiTrust; United States Commission on Civil Rights, Report of the United States Commission on Civil Rights v. 4 (Washington, D.C.: US Government Printing Office, 1961), 1-3, 6, 25, accessed HathiTrust; David MP Freund, Colored Property: State Policy and White Racial Politics in Suburban America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), 99-180; Louis Lee Woods II, “The Federal Home Loan Bank Board, Redlining, and the National Proliferation of Racial Lending Discrimination, 1921-1950” Journal of Urban History vol. 38 no. 6 (2012): 1037-1059, accessed JSTOR.

The 1961 United States Commission on Civil Rights Report on Housing admitted that at the time “housing…seems to be the one commodity in the American market that is not freely available on equal terms to everyone who can afford to pay.” It emphasized that such a gap began “with the prejudice of private persons, but they involve large segments of the organized business world. In addition, Government on all levels bears a measure of responsibility—for it supports and indeed to a great extent it created the machinery through which housing discrimination operates.” The United States federal government became deeply involved in lending and real estate policies following the 1929 stock market collapse and the ensuing Great Depression of the 1930s. The federal government enacted legislation and created regulatory agencies in an attempt to stem the collapse of regional housing markets and bolster the failing economy, and thus began insuring mortgages and educating lenders on risk assessment. In all, it created a new home finance market, which made it safer for lenders to issue mortgage loans and opened home ownership to more Americans (mostly white and middle class), by making it more economically feasible for people to borrow money.

New federal agencies to strengthen the housing and construction market included the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC), the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB), and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). HOLC refinanced home loans for distressed homeowners who could no longer keep up with payments. It became the direct lending and real estate appraisal arm of the FHLB, which supervised all federal savings and loan associations. HOLC introduced appraisal schemes and techniques that analyzed residential neighborhoods to help lenders and real estate agents gauge the risk banks would take on for loans in particular neighborhoods. HOLC policy demonstrated that the agency believed giving mortgages to people of color, especially for homes in all-white neighborhoods, was risky. For example, between 1935 and 1940, HOLC created security maps of neighborhoods in 239 cities that color coded risk. Many neighborhoods were deemed “hazardous” for lending when “undesirable residents” inhabited them. Neighborhoods were coded into four groups, A-D. Awarding an “A” rating meant the neighborhood was the “best” or incurred the lowest risk for the bank, “B” neighborhoods as “still desirable,” “C” neighborhoods “definitely declining” and “D” neighborhoods “hazardous.” When deciding between a “B” neighborhood and a “C” neighborhood, the FHLB asked appraisers to consider if an “encroachment of business or infiltration of a less desirable class of people,” had occurred. If so, according to the FHLB Review “the area is definitely declining in desirability and should be classified as a ‘C’ area.” Only in the ‘B’ areas and above, or those neighborhoods that were all-white, would a mortgage man “make a substantial long-term loan.” The government backing behind these security maps quickly enabled them to become part of standard appraisal practice across the nation. The FHLB corroborated HOLC’s standards by insisting that home finance institutions adopt this appraisal methodology.

The FHA introduced long-term, low-interest, self-amortizing mortgages, which David Freund notes were easier for individuals to pay off. Before, most home mortgages were spread over three to five years and thus required a large “balloon payment” at the end. Furthermore, these FHA loans were insured by the federal government, making them a very low risk for a bank to take on, which allowed many white, middle class Americans to receive a loan in the postwar era and become homeowners. The FHA created standardized, detailed terms and conditions for FHA loans and adopted the appraisal standards HOLC and FHLB had formulated that excluded many racial minorities from receiving these loans. Freund notes their Underwriting Manual (1936), set up “standardized appraisal practices nationwide” and helped lenders and real estate agents determine eligibility of mortgages for federal backing. The manual encouraged appraisers to “investigate areas surrounding the location to determine whether or not incompatible racial and social groups are present,” because “if a neighborhood is to retain stability it is necessary that properties shall continue to be occupied by the same social and racial classes. A change in social or racial occupancy generally leads to instability and a reduction in value.” The manual encouraged the use of municipal zoning and deed restrictions to keep neighborhoods racially homogenous. One of the recommended restrictions home owners could enact over their property included “prohibition of the occupancy of properties except by the race for which they are intended.” It recommended these restrictions should remain valid for all ensuing homeowners for at least twenty years to keep out “adverse influences” to preserve the neighborhood’s homogeneity, both in “type and use of structures and racial occupancy.”

According to Louis Lee Woods, 1 in 3 mortgages for newly constructed homes came from the FHA in 1949. Even though 2 of 3 were outside the FHA, federal government appraisal policies permeated the entire housing market, preventing many African Americans from obtaining mortgages. In 1949, Walter H. Aiken, President of the National Builders Association, testified to the US House of Representatives on behalf of that organization and the National Association of Real Estate Brokers, the National Technical Association, and the National Negro Business League that chief obstacles African Americans encountered included their exclusion from total housing supply and open building sites, reluctance of private lending institutions to finance housing “to the same extent warranted on identical terms and conditions as for others,” and restrictive policies of governmental housing agencies. Freund notes that though the Supreme Court ruled race-based restrictive covenants unconstitutional in Shelly v. Kraemer in 1948, the FHA did not stop publicly endorsing them until 1950. In reality, the FHA only removed explicit references to race from their Underwriting Manual and problems continued. Also, any restrictive covenants recorded before February 15, 1950 continued to receive mortgage insurance from FHA. Though the FHA announced it would not consider racial composition of a neighborhood as an eligibility factor, it remained policy that builders and lenders were free to make their own decisions on who could buy homes built with federal mortgage insurance and discriminatory practices in real estate and home building continued when Better Homes of South Bend was established in 1950.

[4] Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1949), 133, 759; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1950), 379, 782; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1951), 28, 31, 32, 37, 83, 123, 138, 155, 157, 248, 261, 373, 595, 780, 781, 828, 832, 854, 860; “Fact Sheet on Housing,” 1952, Streets Family Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, accessed Michiana Memory; “Testimony on Fair Housing,” 1963, Small Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, 18, accessed Michiana Memory; Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century, 102-103; Leroy Cobb and Margaret Cobb, “Leroy and Margaret Cobb on Better Homes pt. 1,” interview by Adrienne Collier and David Healey, December 11, 2001, transcript, Oral History Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, South Bend, Indiana, 10-12, accessed Michiana Memory; Alan Pinado, “Civil Rights Pioneer Alan Pinado,” interview by Dr. Les Lamon, September 10, 2002, transcript, Oral History Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, South Bend, Indiana, 9-13, accessed Michiana Memory.

Thornbrough notes that African Americans in Indiana, even those with sufficient finances to make down payments, found virtually no homes available to them and no banks willing to loan them money. The housing situation in South Bend was so dire for African Americans, many black families were forced to crowd into one or two room units in substandard buildings. Oral histories attest to the difficulty African American residents had attaining decent housing in the 1950s. Better Homes of South Bend member Leroy Cobb noted, “As far as housing, at the time, you couldn’t move anywhere or buy anywhere in the city.” Alan Pinado, who became one of the only black real estate agents in South Bend in 1960, noted that

There were no first quality homes being built for middle class, middle income blacks in South Bend….The federal government was part and parcel of the segregated housing pattern. It was legally mandated that new communities be kept segregated. The appraisal and underwriting regulations were written in such a way that you must keep neighborhoods homogenous, with the same ethnic group. It was a no-no to introduce any other racial group into an area where it would disturb the values and put the federal government at risk for the FHA program. That was the theory.

The forward to a transcript of a public hearing concerning discrimination in the sale, rental and financing of public housing in South Bend and Mishawaka held on March 19, 1963 at the Notre Dame Law School Auditorium similarly notes that there were only certain “areas a Negro can purchase any home his heart desires and his pocketbook can afford, provided a Negro family is already living on the block. As additional areas that are previously all-white begin to deteriorate, such areas will usually become open to Negro occupancy. These are the only areas, generally speaking, in which Negroes can live.” According to the document, these areas were north of Western Avenue and west of Olive Street, along West Washington Avenue, between Western Avenue and Sample Street west of Prairie Avenue, between Ohio and Keasey Streets, and in northeast South Bend along South Bend Avenue. Reference to an earlier document from 1952, “Fact Sheet on Housing,” shows that many of these areas are within or near three of the four slum areas in South Bend, where all of the Better Homes of South Bend members lived before moving to Elmer Street on the West and South sides of South Bend. Twenty-two of the forty-six members lived along or near Prairie Avenue and six near Western Avenue, both known slum areas. The rest lived north of Western Avenue, between Western Avenue and Lincoln Way West.

[5] Better Homes of South Bend. Meeting Minutes, May 21, 1950, Leroy Cobb Papers, private collection, submitted by applicant; “Testimony on Fair Housing,” ca. 1963, Small Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, accessed Michiana Memory; Leroy Cobb and Margaret Cobb, “Leroy and Margaret Cobb on Better Homes pt. 1,” interview by Adrienne Collier and David Healey, December 11, 2001, transcript, Oral History Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, South Bend, Indiana, 6-8, Michiana Memory.

The first Better Homes of South Bend meeting minute records indicate that the co-op’s lawyer, J. Chester Allen, stressed keeping the group’s activities secret for it to succeed. Secretary Mrs. Louise Taylor defined secrecy as “no information to be given out” in the minutes. Member Leroy Cobb explained the importance of keeping the co-op’s activities out of the public eye in an oral history, explaining right before members moved into their new neighborhood, “We got threatening letters.” Member Margaret Cobb noted that J. Chester Allen would read the letters “to us and it was very, very derogatory, ugly….We had meetings every month, and he [Allen] brought the letter. He said he was going to read the letter because we are having problems. He said this is the letter from the community out there. It wasn’t signed…It just said, ‘You n------ better stay in your place.’ That’s exactly what it said.”

Eighteen South Bend residents testified at a public hearing on housing in South Bend in 1963, either in person or by submitting a written statement, some of which detail racism in the local housing market. For example, a white woman, identified as Mrs. Winona Egendoerfer testified she tried to sell her home in 1961 in South Bend on a “non-discriminatory basis” and listed with a well-known black real estate agent, Will Morris. She said, “I told my husband that it would be put up for anyone that could afford it.” However, once neighbors found out she had enlisted an African American real estate agent, they waited until her husband had left the house and “threw bricks and rocks through the house, through the windows, tore up the aluminum siding.” A week later, she reported that seven teenage girls in the neighborhood beat up her seven year old son in an alley “until he was hemorrhaging.” He had to be admitted to St. Joseph Hospital in South Bend for two weeks. She noted that the neighbors tried to raise enough money to buy the property together, “so it wouldn’t be sold to colored” but they never succeeded. The family had to move because of the violence and ultimately listed with a white realtor to get it sold.

[6]U.S. Congress, House of Representatives, Committee on Banking and Currency. Housing Amendments of 1949: Hearing Before the Committee on Banking and Currency, 81st Cong., 1st sess., 1949, 489; Better Homes of South Bend. Meeting Minutes, May 21, 1950, Leroy Cobb Papers; Better Homes of South Bend. Meeting Minutes, June 18, 1950, Leroy Cobb Papers; Better homes of South Bend, Meeting Minutes, October 19, 1950, Leroy Cobb Papers; Better Homes of South Bend, March 1952, Leroy Cobb Papers; Better Homes of South Bend, Meeting Minutes, April 25, 1952, Leroy Cobb papers; “Testimony on Fair Housing,” 1963, Small Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, 43-46, 48, accessed Michiana Memory; Leroy Cobb and Margaret Cobb, “Leroy and Margaret Cobb on Better Homes pt. 1,” interview by Adrienne Collier and David Healey, December 11, 2001, transcript, Oral History Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, South Bend, Indiana, 4-5, 8, accessed Michiana Memory; Jessica Gordon Nembhard, Collective Courage, 2-13.

Jessica Gordon Nembhard describes a cooperative as “companies owned by people who use their services.” She wrote co-ops are established to “satisfy an economic or social need, to provide a quality good or service (one that the market is not adequately providing) at an affordable price, or to create an economic structure to engage in needed production or facilitate more equal distribution to compensate for a market failure.” There are many types of co-ops, including housing or building co-ops which “expand home or apartment ownership to more people, addressing both financing and maintenance.” Co-ops work by pooling resources to increase benefits and solve economic problems. Nembhard notes African Americans have long established co-ops to address economic racial discrimination. The National Council of Negro Women, Inc. even testified on July 28, 1949 to the House of Representatives at a Housing Amendments of 1949 hearing before the Committee of Banking and Currency that “the highest hope for literally millions of these families [low and middle income racial minorities] is to have access to cooperative or other types of non-profit housing in order to gain a reasonable degree of balance between public and private families to meet their total housing needs.”

According to Better Homes of South Bend meeting minutes, the co-op was able to place an option on land lawyer J. Chester Allen located in South Bend at June 18, 1950, owned by colleague George Sands, to build their community. The group worked with DeHart Hubbard, a new race relations advisor for the FHA in Cleveland and got the FHA to agree to handle their permanent mortgages on October 19, 1950. By November 1951, President Lureatha Allen announced that Better Homes of South Bend had secured permanent financing under the HUD Basic Home Mortgage Loan 203(b). In March 1953, the co-op had secured financing from four local banks for all members. On April 25, 1952, they agreed on two final contractors to handle construction, Hubert Wood Cook and John Skiles. Leroy and Margaret Cobb describe how difficult this process was. Leroy noted “We had a heck of a time trying to find a contractor to build for us.” Margaret noted that many contractors they met with “wanted to give us substandard materials.” Leroy also said, “We ran into opposition for financing. We could not get one bank to finance twenty-six of us. We had to divide it up between, I think there was about six banks.” Leroy notes, “Our credit was nice, so there was no problem about the credit.” Only when Hubbard promised the federal government was backing the loans through FHA could Better Homes in special meetings with local banking representatives could members get local banks to cooperate.

The eighteen testimonies in the document “Testimony on Fair Housing,” demonstrate the prejudiced housing market in South Bend in the 1950s and early 1960s. Mrs. Audrey Vagner, an African American and wife of an African American physician in the city, testified to the difficulty their family had finding a house in 1948 and 1949. She recalls working with several real estate agencies, “in every instance when I asked about a house I was always offered to be shown a house in an all-Negro neighborhood. Usually either the house or the location or both left very much to be desired.” They gave up on purchasing a home and tried to buy land to build their own house. Once they located a potential lot, the seller, once she found out the Vagners were African American “started retreating from her former position of wanting to sell and started making excuses. She blamed the neighbors, she thought the neighbors might object strenuously even though she was willing to sell.” Eventually, the seller’s husband refused to sign the deed. It took the Vagners until 1955 to find a house to purchase. In another instance, from November 1960-August 1963, Mrs. G.L. Ivory, a social worker for the South Bend Urban Renewal Authority, consulted listings in the South Bend newspaper for rentals and house sales that would be within means of both white and black families she worked with. She made an estimated seventy-five calls a week inquiring about these properties. The last question she always asked was if the house or unit was open to “non-white” residents. She testified that about 90% of the people she called responded, “No.”

[7] All documents (deeds) are from Better Homes of South Bend or Better Homes of So Bend Inc to the member(s) name in parentheses after the document number.

Document Name DB0504-0532 (John L. Stanford), DB0504-0533 (Frank Anderson), DB0504-0534 (Robert Allen), DB0504-0535 (Bland Jackson), DB0504-0536 (Albert Warfield), DB0504-0537 (Robert Taylor), DB0504-0538 (Orbry Chambers), DB0504-0539 (Wade Fuller), DB0504-0540 (WC Bingham), DB0507-0405 (John Fleming, Mille Fleming), DB0507-0406 (Gus Watkins, Josie Watkins), DB0507-0407 (Arnold Allen, Lureatha Allen), DB0509-0366 (Willie Gillespie, Marie E Gillespie), DB0512-0498 (Earl Thompson, Viro Thompson), DB0512-0499 (Clint Taylor, Cleopatra Taylor), DB0512-0500 (Frederick D. Coker0, DB0512-0501 (Bozzie Williams, Lila William), DB0512-0502 (James Adams, Florence Adams), DB0512-0503 (Marcus Cecil, Lelar Cecil), DB0512-0504 (Leroy Cobb, Margaret Cobb), DB0513-0564 (Walter Hubbard Jr, Jeanetta Hubbard), DB0513-0565(Sherman Paige, Ruby Paige), St. Joseph County Recorder, South Bend, IN, accessed Land Records Search; Polk’s South Bend City Directory (Detroit, Michigan: R.L. Polk & Co., Publishers, 1956), 782; Leroy Cobb and Margaret Cobb, “Leroy and Margaret Cobb on Better Homes pt. 1,” interview by Adrienne Collier and David Healey, December 11, 2001, transcript, Oral History Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, South Bend, Indiana, 5, accessed Michiana Memory.

Deeds from the St. Joseph County Recorder’s office, accessed online, list twenty-two lots granted from Better Homes of South Bend to members from September 20, 1952 to February 11, 1954. Better Homes of South Bend member Leroy Cobb notes in an oral history that Bland Jackson became the first member to move into his new home on North Elmer Street in 1952. Leroy and his wife Margaret moved in in 1953 and Ruby Paige told him she did not move in until 1954. All the members’ names do not appear in the South Bend City Directory in their residences between 1702-1841 North Elmer Street until 1956.

[8] 1930 US Federal Census, South Bend, St. Joseph County, Indiana, roll 625, page 7B, line 59, accessed AncestryLibrary; Birth Certificate for Raymond Arlen Johnson, September 9, 1937, Indiana State Board of Health. Birth Certificates, 1907-1940. Microfilm. IARA, Indianapolis, IN, accessed AncestryLibrary; 1940 US Federal Census, South Bend, St. Joseph County, Indiana, roll T627_1133, page 2A, line 28 (Clarence Hagedorn), accessed AncestryLibrary; United States Census of Housing, “Block Statistics: South Bend, Indiana,” in 1950 Housing Census Report by Howard G. Brunsman, Volume V, Part 182, (United States Government Printing Office, 1951), 3, 24-25 accessed census.gov; Record of Marriage for Timothy Joseph Eslava, May 23, 1989, Indiana State Board of Health. Marriage Certificates, 1958–2005. Microfilm. IARA, Indianapolis, IN, accessed AncestryLibrary; Death Certificate for Clinton Earl Carson Jr, April 29, 1993, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN, accessed AncestryLibrary; Death Certificate for Theodore Hagedorn, March 26, 1998, Indiana State Board of Health, Death Certificates, 1900-2011, Microfilm, IARA, Indianapolis, IN, accessed AncestryLibrary; Leroy Cobb and Margaret Cobb, “Leroy and Margaret Cobb on Better Homes pt. 1,” interview by Adrienne Collier and David Healey, December 11, 2001, transcript, Oral History Collection of the Civil Rights Heritage Center, Indiana University South Bend Archives, South Bend, Indiana, 7, accessed Michiana Memory; Kathy Bingham to Gabrielle Robinson, email, June 27, 2016, submitted by applicant; Nola Allen to Gabrielle Robinson, letter, June 22, 2016, submitted by applicant; Brenda Williams Wright to Gabrielle Robinson, email, July 1, 2016, submitted by applicant.

Leroy Cobb notes that before Better Homes of South Bend members moved to North Elmer Street, “Everything else was white,” and affirmed that the group lived on two blocks in the middle of a white neighborhood. Leroy Cobb said that once everyone moved in “You know, we didn’t have any problems with our neighbors now, as far as physical or anything like that. I mean everyone was nice. They were nice.” Margaret Cobb clarified, saying “They were nice off a distance, we didn’t say anything to them and they didn’t say anything to us. That’s why they were nice.” Only six households lived in the 1700 and 1800 block of N Elmer Street before Better Homes of South Bend members moved in. According to the 1951 South Bend City Directory, the following households, listed under the following names Clarence Hagedorn at 1705, Clinton E Carson at 1721, Leon Eslava at 1727, Raymond Miller at 1741, Theo Hagedorn at 1742, and Clotiel Johnson at 1838. Death certificates, census records, and marriage certificates indicate all of these households were white. On a broader scope, US Census of Housing Data for 1950 for South Bend divides South Bend into 6 wards and indicates how many non-white households occupied each ward. 1700-1800 blocks of North Elmer Street is located within Ward 1 of South Bend. In 1950, census data indicates that only 7 non-white households occupied Ward 1. In contrast, all Better Homes of South Bend members lived in Ward 2 or Ward 6 before moving to North Elmer Street, each of which contained 530 non-white households and 835 non-white households, respectively.

Emails and letters from member’s children who grew up in the Better Homes of South Bend neighborhood attest to the vibrant community life and how the neighborhood positively impacted their future. Brenda Williams Wright, noted there were lots of family cookouts, outdoor activities like baseball, kickball, and building snowmen, and an annual Elmer Street Parade. Nola Allen wrote that Better Homes allowed her parents to become homeowners, as well as pay for college and law school education for her “while circumventing the impediments of racial discrimination in obtaining land and financing.” Kathy Bingham likewise wrote “Growing up in the Better Homes ‘village’ gave me many advantages that have served me well in my adult life…I don’t think any of us [children in the neighborhood] were fully aware of what our parents accomplished in order to provide that environment for us. We took a lot of it for granted and really didn’t know how unique our neighborhood was until later in life when we saw how some others lived right here in the same city. We never thought of ourselves as above others. What had had wasn’t just better, it was the best.”

Keywords

African American, Historic District