Location: Allen Temple AME Church, 3440 S. Washington St., Marion (Grant County, Indiana), 46953

Installed 2022 Indiana Historical Bureau, Indiana Landmarks, and Friends and Family of Allen Temple

ID#: 27.2022.1

*Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn more about "Marion's Allen Temple and the Importance of Black Spaces"

Text

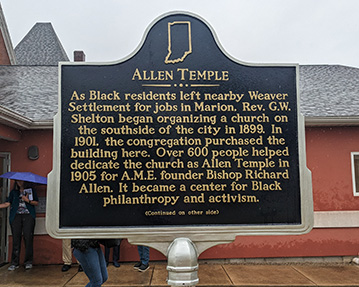

Side One

As Black residents left nearby Weaver Settlement for jobs in Marion, Rev. G. W. Shelton began organizing a church on the southside of the city in 1899. In 1901, the congregation purchased the building here. Over 600 people helped dedicate the church as Allen Temple in 1905 for A.M.E. founder Bishop Richard Allen. It became a center for Black philanthropy and activism.

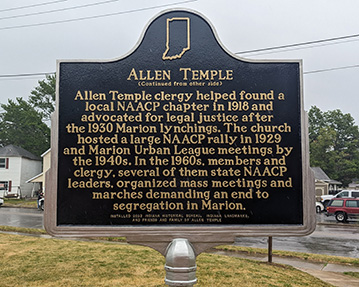

Side Two

Allen Temple clergy helped found a local NAACP chapter in 1918 and advocated for legal justice after the 1930 Marion lynchings. The church hosted a large NAACP rally in 1929 and Marion Urban League meetings by the 1940s. In the 1960s, members and clergy, several of them state NAACP leaders, organized mass meetings and marches demanding an end to segregation in Marion.

Annotated Text

Side One

As Black residents left nearby Weaver Settlement for jobs in Marion,[1] Rev. G. W. Shelton began organizing a church on the southside of the city in 1899.[2] In 1901, the congregation purchased the building here.[3] Over 600 people helped dedicate the church as Allen Temple in 1905 for A.M.E. founder Bishop Richard Allen.[4] It became a center for Black philanthropy and activism.[5]

Side Two

Allen Temple clergy helped found a local NAACP chapter in 1918 and advocated for legal justice after the 1930 Marion lynchings.[6] The church hosted a large NAACP rally in 1929 and Marion Urban League meetings by the 1940s.[7] In the 1960s, members and clergy, several of them state NAACP leaders, organized mass meetings and marches demanding an end to segregation in Marion.[8]

Newspapers accessed Hoosier State Chronicles, Indiana State Library, unless otherwise noted.

[1] “State Enumeration for Legislative and Congressional Apportionment – 1889,” Indianapolis Journal, October 3, 1889, 3; 1900 United States Census, Center Township, Grant County, Indiana, Enumeration District: 0031, FHL microfilm: 1240373, Ancestry.com; “State Enumeration of Voters for the Legislative Apportionment of 1903,” Indianapolis Journal, October 26, 1901, 9; Asenath Peters Artis, “The Negro in Grant County,” 1909, in Centennial History of Grant County, 1812-1912, edited by Ronald L. Whitson (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1914), 354-55 Archive.org. See also state historical marker 27.2020.1 Weaver Settlement.

[2] “Weaver,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 1, 1899, 1; “Weaver,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 4, 1899, 1; “Weaver,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 25, 1899, 1; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, September 15, 1900, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 4, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 15, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 6, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 16, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 16, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 16, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 23, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 23, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 23, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 4, 1902, 1; “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 15, 1902, 3; “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 15, 1902, 3; “South Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, December 27, 1902, 3; “South Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 7, 1903, 3; “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 14, 1903, 2; “South Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 20, 1903, 3; “South Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 20, 1903, 3; Asenath Peters Artis, “The Negro in Grant County,” 1909, in Centennial History of Grant County, 1812-1912, edited by Ronald L. Whitson (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1914), 348-57, Archive.org.

In January 1899, the Indianapolis Recorder reported that Rev. G. W. Shelton of Hill’s Chapel at Weaver Settlement was growing attendance at that congregation. In February of 1899, the same newspaper reported, “G. W. Shelton is soon to begin work on the mission in South Marion.” Secondary sources state that the congregation first gathered at a private home; IHB was unable to confirm this claim with primary evidence. The Marion correspondent for the Indianapolis Recorder reported September 15, 1900, “There has been organized in South Marion an M. E. church and the pastor is here.” A 1909 article stated that the southside Marion A.M.E. congregation purchased the church building at 35th and Washington Streets from a Protestant congregation in 1901.

The newspaper referred to this church as “the South Marion Mission,” “the Methodist South Marion Mission,” “the South Marion Mission Church” from 1899-1902. In 1902, the newspaper began calling the church the “thirty-fifth (or 35th) street A. M. E. church.” These descriptions distinguished it from the A. M. E. church on 5th Street in Marion.

[3] “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 16, 1901, 5; Asenath Peters Artis, “The Negro in Grant County,” 1909, in Centennial History of Grant County, 1812-1912, edited by Ronald L. Whitson (Chicago: Lewis Publishing Co., 1914), 348-57, Archive.org.

Noted local historian Aseneth Peters Artis reported in 1909 that the congregation purchased the current building at Washington and Thirty-Fifth Streets from a Protestant congregation in 1901. Her claim is supported by the Indianapolis Recorder which reported in November 1901 that "the South Marion Mission held services in the Methodist Protestant Church on 35 street."

[4] “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 8, 1905, 3; “Conference Meets,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 22, 1905, 1; “Pastor of the 35th Street Church,” Marion News-Tribune, July 23, 1905, 7, microfilm, Marion Public Library; “Great Event,” Marion News-Tribune, July 24, 1905, 2, Marion and Grant County File, Marion Public Library.

By July 1905, the South Marion Mission, as it was still called (see footnote 2), was represented at the Indiana Conference of A.M.E. Churches and the congregation completed a remodel of the building. The Marion News-Tribune reported that on July 23, 1905, “more than six hundred colored people,” leading Indiana clergy, “the colored Masons,” and the Marion mayor were among those who attended a “grand rally” at the church. During this ceremonial celebration, the congregation dedicated the church as Allen Temple, named for Bishop Richard Allen, founder of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

[5] “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 16, 1901, 5; “Marion Flashes,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 4, 1902, 1; “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 15, 1902, 3; “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 13, 1907, 3; “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 7, 1908, 3; “$400, Piano Free,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 28, 1908, 1; Margaret F. Gulliford, “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, May 22, 1915, 2; Margaret F. Gulliford, “Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 26, 1915, 2; Joe Wells, “Marion, Indiana,” Indianapolis Recorder, December 24, 1938, 7; Joe Wells, “Marion, Indiana,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 29, 1939, 15; “Marion, Indiana,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 25, 1939, 15; Joe Wells, “Marion, Ind.,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 20, 1940, 13; Joe Wells, “Marion, Ind.,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 27, 1940, 13; Joe Wells, “Marion, Ind.,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 24, 1940, 15; “Marion Group Aids Red Cross,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 31, 1942, 14; Lillian Ward, “Marion, Ind.,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 29, 1944, 5; “A. C. E. League,” in R. R. Wright, Jr., Doctrines and Discipline of the A. M. E. Church (Philadelphia: A. M. E. Book Concern, 1916), 385, Google Books.

After growing the congregation, creating a choir, raising funds, and establishing itself in the community through social events, Allen Temple leaders and members turned to improving that community. Several women’s groups, including the Busy Bee Club and the Women’s Mite Missionary, were active by 1915. By the 1930s, Allen Temple hosted a local Welfare League, Boy Scout Troop No. 4, and the A. C. E. League, which dedicated to being “an uplifting force in all departments of life” for the congregation’s younger members. Other clubs included the Willing Workers, the Townsend Club, and the Anchor Club. During WWII, the church hosted a “coal rally” and longtime member Pearl Bassett and others raised money for the Red Cross to support the war effort. For information on activism see footnotes for side two.

[6] Marion Indiana Branch National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Application for Charter, November 28, 1918 (organization date), NAACP Founding Documents, Library of Congress, copy in IHB marker file; “A. M. E. Church Appointments Made Public,” Indianapolis Times, October 1, 1929, 16; “Soldiers Stand Guard at Graves While Victims of Lynching Mob Are Buried,” Indianapolis Times, August 11, 1930, 1; “Grant Sherriff’s Ousting Is Asked,” Indianapolis Star, August 21, 1930, 9, Newspapers.com; James Madison, A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 5-11; Nicole Poletika, “From Strange Fruit to Seeds of Change? The Aftermath of the Marion Lynching,” Indiana History Blog, July 13, 2020, blog.history.in.gov.

Rev. W. C. Irvin of Allen Temple was among the charter members of the Marion chapter of the NAACP in 1918. In the subsequent years and decades, Allen Temple clergy continued to serve as active NAACP leaders at the local and state level.

After the lynching of Thomas Shipp and Abram Smith in Marion on August 7, 1930, Marion ministers and civic leaders called for peace and organized to pursue justice. Rev. Hillard D. Saunders (appointed to Allen Temple in 1929) was among those who signed a petition demanding the governor remove the sheriff for failing to protect Shipp and Smith from the mob.

[7] “Marion Group to Escort DePriest,” Kokomo Tribune, September 7, 1929, 11, Newspapers.com; Merle L. Thruston, “Marion, Ind.,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 24, 1945, 15; “Urban League Guild Votes to Buy Drapes,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 23, 1954, 4; “Marion Urban League Sets Date for Membership Drive in June,” Indianapolis Recorder, March 27, 1954, 14; “Marion Women Sponsor Party,” Indianapolis Recorder, April 10, 1954, 5; “150 Attend Annual Board Meeting Held Monday Night,” Indianapolis Recorder, November 26, 1955, 9; James Madison, A Lynching in the Heartland: Race and Memory in America (New York: Palgrave, 2001), 60; Nicole Poletika, “Strange Fruit: The 1930 Marion Lynching and the Woman Who Tried to Prevent It,” Indiana History Blog, May 15, 2018, blog.history.in.gov.

In September 1929, Indiana NAACP leader Katherine “Flossie” Bailey brought African American U.S. Representative Oscar DePriest to Allen Temple. Speaking to a large crowd of Black congregants and residents, DePriest called on the audience to vote and “to stand together,” according to historian James Madison. The Kokomo Tribune reported that the congressman spoke first in Kokomo and was then escorted to Allen Temple by the Marion NAACP.

In 1945, “John C. Dancy, executive secretary of Detroit Urban league . . . spoke at the Allen Temple,” according to the Indianapolis Recorder. In 1947, the annual meeting of the Marion Urban League was held at Allen Temple. In 1949, the Marion Urban League based its membership campaign there and Rev. W. T. Alexander of Allen Temple gave the benediction at the Ninth Annual Meeting of the Marion Urban League. By the 1950s, prominent Allen Temple member Pearl Bassett also served as an active member of the Marion Urban League and the Marion Urban League Guild, which was organized “to assist in activities of cultural, civic and social nature which will further the Urban League movement,” according to the Indianapolis Recorder.

[8] “Negro’s Job Dilemma Stymies Economy, Beckwith Asserts,” Indianapolis Recorder, February 3, 1962, 3; “Marion Hotel Owner Under ‘Bias Fire:’ Ind. Postmaster Party to Charge of Jimcrowism,” Indianapolis Recorder, June 30, 1962, 1; “AME Minister Scores Racial Bias at Marion, Ind,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 7, 1962, 1; “NAACP Protests Racial Atrocities at Marion,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 5, 1969, 1; Annette L. Anderson, “NAACP Victorious Then and Now,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 10, 1993, 11; Pearl Bassett, Oral History Interview, 2009, University of Southern Indiana, University Archives and Special Collections, David L. Rice Library, University of Southern Indiana; Madison, 140.

In 1962, Allen Temple hosted “prominent Indianapolis attorney and civil rights leader” Frank R. Beckwith who spoke on employment equality. Also in 1962, Rev. B. A. Foley of Bethel AME and Rev. Ford Gibson of Allen Temple led a campaign demanding an “immediate investigation and the removal” of Marion Postmaster Charles R. Kilgour. The pastors charged that Kilgour, as president of the Francis Marion Hotel, which “allegedly refused to accommodate Negroes,” should be removed from his position as postmaster. Foley and Gibson publicly called on Attorney General Robert Kennedy to act. Rev. Gibson, who had also served as president of the Indiana chapter of the NAACP, addressed a crowd of 300 people at a mass meeting. According to the Indianapolis Recorder, the pastor stated that the Black residents of Marion “will not stop until segregation is dead and buried and never to rise again.”

In July of 1969 the NAACP responded to reports from the Marion branch of daily “racial atrocities in the city, including police brutality against Black residents, unprovoked attacks by whites on Black youth, and unjust and illegal arrests and incarceration of young Black Marion residents. The NAACP called for action and organized a march. According to historian James Madison, “The march leaders presented the city with a manifesto. It called for equal employment and educational opportunities, equal housing, more black teachers. And more black history programs in schools.” They called for local businesses and unions to cease racist activity and for desegregation of the local roller rink. Allen Temple member and NAACP leader Pearl Bassett recalled that the marchers demanded desegregation of Marion businesses and equal hiring practices. She recalled: “We first had the walk from 26th Street to the courthouse for discrimination and equal opportunities for people and jobs. And it was a wonderful thing.” She told the Indianapolis Recorder: “It was so well organized and we accomplished what we set out to do.”

Keywords

African American, Religion