Location: West 21st Street and North Boulevard Place, Indianapolis (Marion County, Indiana) 46202

Installed 2019 Indiana Historical Bureau, The American Legion, The Association for the Study of African American Life and History, and those dedicated to the memory of Joseph H. Ward, M.D.

ID#:49.2019.3

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn "How Indianapolis Surgeon Dr. Joseph Ward Challenged the Jim Crow South"

Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn "How Indianapolis Surgeon Dr. Joseph Ward Challenged the Jim Crow South"

Text

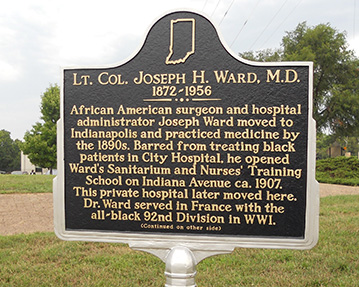

Side One

African American surgeon and hospital administrator Joseph Ward moved to Indianapolis and practiced medicine by the 1890s. Barred from treating black patients in City Hospital, he opened Ward’s Sanitarium and Nurses’ Training School on Indiana Avenue ca. 1907. This private hospital later moved here. Dr. Ward served in France with the all-black 92nd Division in WWI.

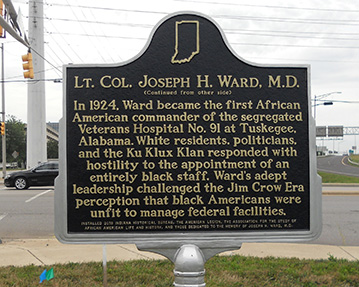

Side Two

In 1924, Ward became the first African American commander of the segregated Veterans Hospital No. 91 at Tuskegee, Alabama. White residents, politicians, and the Ku Klux Klan responded with hostility to the appointment of an entirely black staff. Ward’s adept leadership challenged the Jim Crow Era perception that black Americans were unfit to manage federal facilities.

Summary

Dr. Ward is as foundational to Indianapolis's rich African American history as The Freeman publisher Dr. George Knox and entrepreneur Madam C.J. Walker, whom he helped her start in her adopted city. Born in Wilson, North Carolina to impoverished parents, young Ward traveled to Indianapolis in search of better opportunities. He attended Shortridge High School and worked as the personal driver of white physician George Hasty. According to The Freeman, Dr. Hasty "'said there was something unusual in the green looking country boy, and to the delight of Joe as he called him, he offered to send him to school.'" By the 1890s, Ward had earned his degree from the Indiana Medical College and practiced medicine in Indianapolis. Barred from treating Black patients in city hospitals, he opened Ward’s Sanitarium and Nurses’ Training School on Indiana Avenue around 1907. He also convinced administrators at the segregated City Hospital to allow Black nurses to take courses alongside white students. This opened professional opportunities to African American women in an era in which they were often relegated to domestic service and manual labor. Ward also gave back to his city by helping found the African American Senate Avenue YMCA.

Dr. Ward temporarily left his practice to serve in the Medical Corps in France with the 92nd Division Medical Corps. He became one of two African Americans to achieve the rank of Major in World War I. During Ward’s absence, his brother-in-law, Dr. M.D. Batties, temporarily took over the sanitarium. In 1924, Dr. Ward became the first African American commander of the segregated Veterans Hospital No. 91 at Tuskegee, Alabama. With his appointment, the hospital's staff was composed entirely of Black personnel. These pioneering practitioners treated Southern Black veterans, many suffering from PTSD following WWI service. Ward's decision to accept the position was itself an act of bravery, coming on the heels of hostility from white residents, politicians, and the Ku Klux Klan.

Under Ward's leadership, the Buffalo American reported, patients "are happy, content and enjoying the best of care at the hands of members of their own race who are inheritently [sic] interested in their welfare." The Journal of the National Medical Association noted in 1962 that Ward "amassed an enviable reputation in the Tuskegee community. His legendary inspection tours on horseback and his manly fearlessness in dealing with community groups at a time when there was a fixed subordinate attitude in Negro-white relations." Dr. Ward proved so adept as a leader that the War Department promoted him to Lieutenant Colonel. A 1929 editorial for the JNMA praised Ward for his ability "to win over to your cause the White South" and noted "'Those who led the opposition to the organization of a Negro personnel openly and frankly acknowledge their mistake and their regret for the earlier unfortunate occurrences.'" President Calvin Coolidge concurred with these characterizations in an address to Congress. In 1937, Ward pled guilty to "conspiracy to defraud the Government through diversion of hospital supplies." African American newspapers contended that the “trumped up charges” were an attempt by the Democratic administration to replace Black personnel with white. Ward quietly returned home to Indianapolis and resumed his private practice, which had moved to Boulevard Avenue. At a time when African Americans were often excluded from medical treatment, Dr. Ward made care accessible to those in Indianapolis and, on a much larger scale, to Southern veterans.

Annotated Text

Side One

Lt. Col. Joseph Ward, M.D. (ca. 1872-1956) [1]

African American surgeon and hospital administrator Joseph Ward moved to Indianapolis and practiced medicine by the 1890s.[2] Barred from treating Black patients in city hospitals,[3] he opened Ward’s Sanitarium and Nurses’ Training School on Indiana Avenue ca. 1907.[4] This private hospital later moved here.[5] Dr. Ward served in France with the 92nd Division Medical Corps in WWI.[6]

Side Two

In 1924, Ward became the first African American commander of the segregated Veterans Hospital No. 91 at Tuskegee, Alabama.[7] White residents and the Ku Klux Klan responded with hostility to the appointment of an entirely Black staff.[8] Despite this, Ward’s adept leadership challenged the Jim Crow Era perception that Black Americans were unfit to manage federal facilities.[9]

[1] “Dr. Joseph H. Ward,” The Freeman (Indianapolis), July 22, 1899, 1, 4, accessed Google News; “Joseph H Ward,” 1900 United States Federal Census, Indianapolis, Marion County, Indiana, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Joseph H. Ward,” Indiana, Select Marriages Index, 1748-1993, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Joseph Ward,” Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York (including Castle Garden and Ellis Island), 1820-1957, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; “Ward, Joseph Henry,” U.S. Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, applied for on April 8, 1957 by Susan Knox Ward, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Dr. Joseph Ward Rites Saturday,” The Indianapolis News, December 13, 1956, accessed Newspapers.com.

Sources conflict regarding the year Ward was born. Some newspaper articles state that he was born in 1870, as do the 1900 U.S. Federal Census and Indiana Select Marriage Index. However, the U.S. Headstone Applications for Military Veterans and Passenger Lists of Vessels Arriving at New York note he was born in 1872. Census records report that he was born anywhere between 1870 and 1875. To err on the side of caution, the marker text lists his date of birth as circa 1872.

[2] “Dr. J. H. Ward Honored,” The Freeman (Indianapolis), October 23, 1897, 4, accessed Google News; Advertisement, “Joseph H. Ward, Physician and Surgeon,” The Freeman (Indianapolis), December 18, 1897, 8, accessed Google News; “Dr. Joseph H. Ward,” The Freeman (Indianapolis), July 22, 1899, 1, 4, accessed Google News; “Joseph H. Ward,” 1898, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, accessed AncestryLibrary.

[3] Wm. H. Walsh, The Hospitals of Indianapolis: A Survey (Indianapolis Foundation, 1930), Chapter “Hospitals for the Colored,” submitted by applicant; “A Negro Hospital,” Indianapolis Recorder, July 17, 1909, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Lincoln Hospital,” Indianapolis Recorder, October 2, 1909, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Emma Lou Thornbrough, Indiana Blacks in the Twentieth Century (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000), 27; Norma B. Erickson, “African-American Hospitals and Health Care in Early Twentieth Century Indianapolis, Indiana, 1894-1917,” master’s thesis, Indiana University, 2016, 4, 8, 27, 32, accessed IUPUI ScholarWorks Repository.

[4] “Sensation,” The Freeman (Indianapolis), December 28, 1907, 8, accessed Google News; “New Sanitarium: Operated by Dr. J. H. Ward With Training School for Nurses at the Hoosier Capital,” The Freeman (Indianapolis), June 19, 1909, 3, accessed Google News; “Dr. Ward’s Sanitarium and Hospital,” Indianapolis Recorder, August 7, 1909, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Advertisement, “Dr. Ward’s Sanitarium and Training School for Colored Nurses,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 8, 1910, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; S. Ethel? Clark, Inspector, to Mr. Amos W. Butler, Secretary, January 17, 1910, Indiana State Archives?, submitted by applicant; Erickson, 30, 59, 64-65.

Although Ward had been practicing medicine by the 1890s, it is unclear when he officially opened Ward’s Sanitarium and Nurses’ Training School on Indiana Avenue. City directories note that he had already been practicing on Indiana Avenue, possibly out of his residence, before the Indianapolis Recorder reported in 1907 that his “new” sanitarium opened. His brother-in-law temporarily took over the sanitarium when Ward left for service in the Medical Corps during World War I. The 1922 city directory notes that his practice moved to 2116 Boulevard Place and records show that he operated there until at least 1949.

See this spreadsheet for a comprehensive list of addresses for Ward’s residences and offices.

[5] “Ward, Joseph H.,” 1922, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Ward’s Sanitarium,” 1924, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, accessed AncestryLibrary; Advertisement, “Dr. M. D. Batties’ Sanatarium,” Indianapolis Recorder, January 2, 1926, 7, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Wm. H. Walsh, The Hospitals of Indianapolis: A Survey (Indianapolis Foundation, 1930), Chapter “Hospitals for the Colored,” submitted by applicant; Study, Leona Massoth, Child Welfare Worker, Visited Ward Sanitarium (Colored) (Formerly Community Hospital), June 17, 1938, Indiana State Archives?, submitted by applicant; F.E. Hall, Ward’s Sanitarium, to Miss Leona Massoth, Children’s Division, Dept. of Public Welfare, April 10th 1939, submitted by applicant; “Ward, Joseph H.,” 1940, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Ward, Jos, H,” 1949, U.S. City Directories, 1822-1995, accessed AncestryLibrary.

[6] “Medical Officer Promoted,” The Indianapolis Star, January 2, 1919, accessed Newspapers.com; “Joseph H Ward,” Departure Date, February 2, 1919, U.S., Army Transport Service, Passenger Lists, 1910-1939, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Maj. Ward Back from U.S. Work,” The Indianapolis Star, June 29, 1919, accessed Newspapers.com; “Major Ward Appointed,” The Buffalo American, October 30, 1924, accessed Newspapers.com; “Ward, Joseph Henry,” U.S. Headstone Applications for Military Veterans, 1925-1963, applied for on April 8, 1957 by Susan Knox Ward, accessed AncestryLibrary; Darlene Richardson, Historian, Veterans Health Administration, “Tuskegee Hospital,” VA History Highlights, VA Pittsburgh Healthcare System, accessed U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs.

[7] “Negro Head Tuskegee Hospital,” The Times (Montgomery, AL), July 9, 1924, accessed Newspapers.com; “Tuskegee Hospital in Negro Control,” The Baltimore Sun, July 14, 1924, accessed Newspapers.com; “Tuskegee Hospital,” Baltimore Afro American, July 11, 1925, A9, accessed Newspaper Archive; Col. J. H. Ward, M.D., Medical Officer-in-Charge, “U.S. Veterans’ Hospital, Tuskegee, Alabama,” Journal of the National Medical Association 22, no. 3 (July-September, 1929): 133-134, accessed U.S. National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health; “Joseph H Ward,” 1930 United States Federal Census, Tuskegee, Macon County, Alabama, accessed AncestryLibrary; “Dr. Joseph Ward Rites Saturday,” The Indianapolis News, December 13, 1956, accessed Newspapers.com; Richardson, “Tuskegee Hospital.”

[8] State Senator R. H. Powell, “How U.S. Government Broke Faith with Whites and Blacks of Tuskegee, Ala.,” The Montgomery Advertiser, June 23, 1923, accessed Newspapers.com; Atticus Mullin, “Negro Dentists Reach Tuskegee is Report Sunday,” The Montgomery Advertiser, June 25, 1923, accessed Newspapers.com; “The Tuskegee Hospital,” The Crisis 26, no. 3 (July 1923), accessed Google Books; “Tuskegee Hospital in Negro Control,” The Baltimore Sun, July 14, 1924, accessed Newspapers.com; Editorial, “The U. S. Veterans’ Hospital, Tuskegee, Ala., Colonel Joseph Henry Ward,” Journal of the National Medical Association 21, no. 2 (1929): 65-67, submitted by applicant; Vanessa Northington Gamble, Making a Place for Ourselves: The Black Hospital Movement, 1920-1945, (New York: Oxford University Press, 1995), Chapter 3 “’Where Shall We Work and Whom Are We to Serve?’ The Battle for the Tuskegee Veterans Hospital;” Richardson, “Tuskegee Hospital.”

[9] “Ward Wants Vet’s Hospital to Unite With Tuskegee,” The Pittsburgh Courier, July 4, 1925, accessed Newspapers.com; “Tuskegee Institute Carries on Program…,” The Montgomery Advertiser, March 15, 1928, accessed Newspapers.com; Editorial, “The U. S. Veterans’ Hospital, Tuskegee, Ala., Colonel Joseph Henry Ward,” Journal of the National Medical Association 21, no. 2 (1929): 65-67, submitted by applicant; “Col. Ward,” Baltimore Afro American, June 13, 1931, accessed Newspaper Archive; Clifton O. Dimmitt, D.D.S. and Eugene H. Dribble, M.D., “Historical Notes on the Tuskegee Veterans Hospital,” Journal of the National Medical Association 54, no. 2 (March 1962): 134-135; Northington, Chapter 3.