Location: Near 600 Jackson St., Columbus, (Bartholomew County, Indiana) 47203

Installed 2013 Indiana Historical Bureau and Joseph Hart Chapter, National Society Daughters of the American Revolution

ID#: 03.2013.1

Text

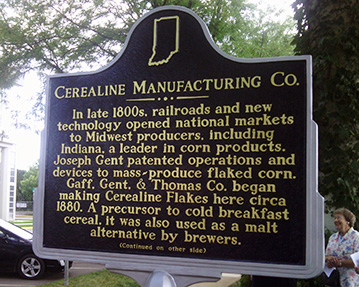

Side One:

In late 1800s, railroads and new technology opened national markets to Midwest producers, including Indiana, a leader in corn products. Joseph Gent patented operations and devices to mass-produce flaked corn. Gaff, Gent, & Thomas Co. began making Cerealine Flakes here circa 1880. A precursor to cold breakfast cereal, it was also used as a malt alternative by brewers.

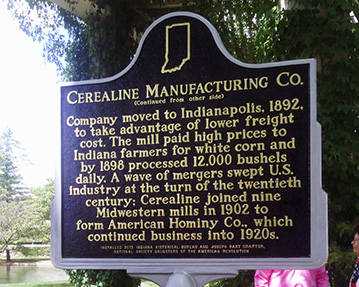

Side Two:

Company moved to Indianapolis, 1892, to take advantage of lower freight cost. The mill paid high prices to Indiana farmers for white corn and by 1898 processed 12,000 bushels daily. A wave of mergers swept U.S. industry at the turn of the twentieth century; Cerealine joined nine Midwestern mills in 1902 to form American Hominy Co., which continued business into 1920s.

Annotated Text

Side One

In late 1800s, railroads and new technology opened national markets to Midwest producers,[1] including Indiana, a leader in corn products.[2] Joseph Gent patented operations and devices to mass-produce flaked corn.[3] Gaff, Gent, & Thomas Co.[4] began making Cerealine Flakes here circa 1880.[5]. A precursor to cold breakfast cereal,[6] it was also used as a malt alternative by brewers.[7]

Side Two

Company moved to Indianapolis, 1892, to take advantage of lower freight cost.[8] The mill paid high prices to Indiana farmers for white corn and by 1898 processed 12,000 bushels daily.[9] A wave of mergers swept U.S. industry at the turn of the twentieth century;[10] Cerealine joined nine Midwestern mills in 1902 to form American Hominy Co.,[11] which continued business into 1920s.[12]

[1] Annual Report of the Commissioner of Patents (Washington, DC.: Government Printing Office, 1893), v, accessed Archive.org; U. S. Patent Activity, Calendar Years 1790 to the Present, U.S. Patent and Trademark Office accessed www.uspto.gov/web; Clifton J. Phillips, Indiana in Transition, The Emergence of an Industrial Commonwealth 1880-1920 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau and Indiana Historical Society, 1968), 137-44, 271-74, 279-83; James H. Madison, ed., Heartland (Indiana University Press: Indianapolis, 1988), 5,138-40, 211, 270-72, 286-88; Naomi R. Lamoreaux and Kenneth L. Sokoloff, “Long-Term Change in the Organization of Inventive Activity,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 93:23 (November 12, 1996): 12686-12692 accessed Jstor.org/stable/40682 ; Nancy Koehn, “Henry Heinz and Brand Creation in the Late Nineteenth Century: Making Markets for Processed Food,” The Business History Review 73:3 (Autumn 1999): 349, 351, 364, accessed JSTOR.org, doi: 3116181; Cerealine Manufacturing Company, Cereal Foods (Cincinnati, Ohio: McDonald & Eick, 1886), [3, 4, 6, 16]; Harvey Levenstein, “The New England Kitchen and the Origins of Modern American Eating Habits,” American Quarterly 32:4 (Autumn 1980): 369-386, accessed JSTOR doi: 2712458.

The U.S. Commissioner of Patents, in 1892, bragged that “America has become known to the world as the home of invention.” At the turn of the century, invention was at an all-time high, growing from less than 4,500 patents issued per year in the 1850s to more than 23,000 in the 1890s. This inventive boom revolutionized business and communication, journalism and photography, transportation, science, and the American diet. Innovations in refrigeration and transportation made it possible to transport foods with a very short shelf-life cross-country, and innovations in food processing and sanitation allowed new convenience foods into the market.

According to Clifton Phillips, Indiana’s industries began to grow rapidly in the 1880s due to four factors: large quantities of agricultural and forest resources; available coal and natural gas; excellent railroads; and location near the center of the country. Phillips classes processed foods in the late 1800s as meatpacking, flour milling, and the production of corn grits and hominy. In the Midwest, the number of U.S. patents issued per capita grew at the same time as industrialization expanded beginning in the early nineteenth century. Authors Lamoreaux and Sokoloff chart the numbers of patents for specific decades and geographic locations from 1840 to 1911. In the region that includes Indiana, the greatest increase in patents corresponds to growth of railroad transportation and market expansion in the region.

Historian of business, Nancy Koehn, suggests that the growing availability of processed foods eventually changed the eating habits of millions of consumers in the U.S. Food producers began marketing the “purity and quality” of these products as well as the time-saving benefits for the homemaker. New scientific technologies especially helped to open new markets, legitimizing manufacturers’ marketing of processed foods as nutritionally-superior. Food historian Harvey Levenstein explains that nutritional science began to be popular in the U.S. in the 1880s and by the 1890s was being used by reformers to change the way America ate. “Scientific eating” proponents believed that the most healthful foods were those with the most ideal balance of nutrients, determined by laboratory analysis. They intended to reform the lower classes and improve the economy by spreading the word that the carbohydrates, fats, and proteins in a cheap food product were no different than those in a top-of-the line variety. By minimizing food expense and cost of living, they might then maximize lower class spending on goods and services and keep labor costs low for maximum industrial growth. This early analysis was ignorant of vitamins and minerals. Though ineffective as a reform for the poor, the movement eventually got through to the middle classes via home economics classrooms and community lunch rooms.

Like many turn-of-the-century brands, Cerealine Manufacturing Company used scientific inquiry popularized by proponents of “scientific eating” to demonstrate the superior nutritional profile of their foods, sharing expert chemical analysis of Cerealine Flakes and common “whole” foods like oatmeal and rice in advertising. Published in 1886 by Cerealine Manufacturing Co., Cereal Foods made this claim: “Cerealine Flakes, made from pure white Maize, contains, by the exactest chemical analysis, more actual nourishment than any other preparation of the cereals, and this nourishment is, by the exactest test, more digestible than that of any other farinaceous [i.e., starchy] food known.”

[2] Clifton J. Phillips, Indiana in Transition, The Emergence of an Industrial Commonwealth, 1880-1920 (Indianapolis, IN: Indiana Historical Bureau & Indiana Historical Society, 1968), 279, 282-83; U.S. Department of the Interior, Census Office, Report on the Productions of Agriculture, Tenth Census (Washington, DC: GPO, 1883), xvii; U.S. Department of the Interior, Census Office, Census Reports, VI, Agriculture, Part II, Crops and Irrigation 1900 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1902), Section I, Cereals, 22-23; U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Vol. 5, Agriculture, General Report and Analytical Tables, 1920, (Washington, DC: GPO, 1922), Chapter XII, Table 9, 736, accessed www.agcensus.usda.gov/Publications/Historical_Publications;

U.S. Department of Commerce and Labor, Bureau of the Census, Vol. IX, Manufactures, 1909 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1912), 304, 317, 318; U.S. Department of Commerce, Bureau of the Census, Vol. X, Reports for Selected Industries, 1920 (Washington, DC: GPO, 192?), Flour-Mill and Gristmill Products, Table 3, 105, Table 15, 113.

Indiana historian, Phillips cites the state’s production of cereal grains as an important element in the growth of manufacturing in Indiana from 1880 to 1920. In fact, the milling of cereal grains, primarily wheat and corn, became Indiana’s leading industry in the 1880s and 1890s. And as Indiana’s production of wheat and wheat flour declined, the state “remained the leading producer [of hominy and grits] in the country through nearly the whole of this period [1880-1920].”

U.S. Census of Agriculture reports confirm Phillip’s statements. In 1880, Indiana ranked 4th in the country in bushels of “Indian corn” produced. In 1900, Indiana ranked 6th in corn production; in 1909, the state ranked 3rd in corn production. And in 1919, the state was the 4th largest corn producer in the United States.

The various reports of the U.S. Census of Manufactures are more complicated to interpret because of changes in terminology and in reporting. In 1880, Indiana ranked 10th in the number of bushels of processed “flouring and gristmill products.” By 1899, the state was ranked 6th, (but dropped back to 8th in 1909 where it remained in 1919. However, by 1909, Indiana’s production of corn hominy and grits had increased 200% in quantity and 400% in value. By 1919, the state ranked 2nd in the U.S. in the quantity and value of its processed hominy and grits.

[3] A Biographical History of Eminent and Self-Made Men of the State of Indiana I (Cincinnati, OH: Western Biographical Publishing Company, 1880), 15; See also US Patents 223847, 262761, 302200, 302199, 302198, 304722, 312265, 372065, 388962, 395893, 581908, 707058, 727345, 731106, 735664, 735662, 379377, and 379378, accessible via digital download from the United States Patent and Trademark Office.

According to a contemporary biography, Gent was “considered the most successful mill builder and remodeler in the United States,” and had even traveled abroad to redesign European mills. Joseph F. Gent was a prolific inventor and successfully patented at least sixteen milling and brewing apparatuses and processes.

[4] Cerealine Manufacturing Company Sales Invoice, private collection of "R.E.R.," December 7, 1886, accessed http://columbusin.proboards.com/thread/57/cerealine?page=2 ; Richard Thomas to Thomas Gaff, Esq. (letter), February 12, 1872, Gaff Mss., Lilly Library, IU Bloomington; Notice of dissolution of Thos. Gent & Co., Jan. 16, 1871, Gaff Mss. , Lilly Library, IU Bloomington; Letter fragment, Gaff, Rush & Thomas to Germania Savings Bank (Charleston, SC), private collection of “R.E.R.,” October 27, 1877, accessed 10/26/12, columbusin.proboards.com; Cline & McHaffie, The People’s Guide. . . A Business, Political and Religious Directory of Bartholomew Co., Ind. (Indianapolis, Ind.: 1874), 157, 177; Haddock & Brown's General & Business Directory of Madison, Columbus, and Vevay, IN for 1879, p. 143; Edmundson, Columbus City Directory 1875, p. 21; J. H. DeBeers & Co., Atlas of Bartholomew County (Chicago, Ill.: J. H. DeBeers & Co., 1879), 8-9, Indiana State Library microfilm.

An 1886 Cerealine Manufacturing Company invoice notes that the company is a “Successor to Gaff, Gent & Thomas.” Surviving letters and city directories indicate that Thomas Gent, Thomas Gaff, and James W. Gaff formed a milling operation in Columbus, IN prior to 1871, but dissolved the enterprise in that year. Members of the Gaff family, by 1875, were involved in at least two partnerships: Gaff, Rush & Thomas and Gaff & Thomas. The principal business of Gaff, Rush & Thomas was Haw Patch Hominy Mills on Franklin St. in Columbus, IN, which produced steam-dried hominy products. Lowell Mills [wheat] Flour was produced under the auspices of a separate company, Gaff & Thomas. The Gent family also appears in city directories as early as 1879, milling flour. How Joseph Gent (son of Thomas) became involved with the Gaff and Thomas corn milling endeavors, and how Rush left the enterprise, is unclear.

[5] "Columbus, Ind., Jan. 1886," Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 2; "Columbus, Ind., Dec. 1892," Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps, 2. Leading Industries of the Principal Places in Decatur, Bartholomew, Jackson, and Lawrence Counties, Indiana, 1885, p. 71; Joseph F. Gent, Prepared Cereal, US Patent 223847, filed September 1, 1879, issued January 27, 1880; Joseph F. Gent, Art of Making A Product from Indian Corn Known as Cerealine, US Patent 304722, filed November 17, 1883, issued September 9, 1884; Certificate of Incorporation, October 16, 1886, Indiana State Archives, Indiana Commission on Public Records, 746-72, copy; J. H. DeBeers & Co., Atlas of Bartholomew County (Chicago, Ill.: J. H. DeBeers & Co., 1879), 8-9, Indiana State Library microfilm.

The Cerealine and Pearl Meal Mill of Gaff, Gent & Thomas was located between 7th St. and 6th St. on Jackson St. in Columbus, IN. An 1885 profile of the company dates the debut of Cerealine Flakes to 1881, but Joseph F. Gent, on behalf of Gaff, Gent & Thomas, filed a patent, number 223847, in 1880 for a new corn product that could be kept "in any climate" and consisted of "dry flakes made from clipped and purified kernels of corn." The ground meal was flash-steamed so as to remain uncooked but softened, and the granules were rolled into flakes while warm, then dried. Though many adjustments (including an increase in refining to include only the starchy part of the corn kernel in the finished product) to the manufacturing process were patented by Gent in subsequent years, the shelf-stable flakes referenced in this patent appear to be an early form of the trademarked product. Gent’s later patent, number 304722, references this early product and explains that it is now known in the market as “Cerealine.” While it is evident the company marketed Cerealine and owned a milling site as early as 1880, Cerealine Manufacturing Company did not officially incorporate until 1886.

[6] Cereal Foods, pp. [9, 11, 13]; “Cerealine,” What’s On the Menu, New York Public Library, accessed Aug. 30, 2012; US Patent 223847, 1880; Joseph F. Gent, Art of Brewing Malt Liquors, Specification forming part of Patent 262761, filed January 26, 1882, issued August 15, 1882; US Patent 304722, 1884; US Patent 372065, 1887; Advertisement, Logansport (Ind.) Journal, December 25, 1906, 4.

Cerealine publications, like Cereal Foods, reference “over 200” ways to prepare the flakes. Cerealine appears on numerous historic restaurant, hotel, and ship menus in the New York Public Library’s collection, alongside oatmeal and other hot cereal preparations, in addition to appearing as the main ingredient in cakes, fritters, puddings, and other recipes. Cerealine Flakes predates the processed and flaked breakfast cereals modern American consumers might be familiar with, Kellog’s Corn Flakes (1894) and Post Toasties (1904). The flakes were easily soluble in liquid, a selling point for the brewing industry and home cooks looking for quick meal solutions. No modern version of Cerealine exists in the U.S., but patent descriptions and the menus and recipes published at the turn of the century suggest that this early version of prepared Cerealine flakes was soft in texture, more similar to porridge than to the crunchy breakfast cereals consumed today.

[7] Cereal Foods, p. 6; US Patent 223847, 1880; Art of Brewing Malt Liquors, Specification forming part of Patent 262761, filed January 26, 1882, issued August 15, 1882; Advertisement 6, Harper’s Bazaar, Jul. 16, 1887, 20, 29 American Periodicals p. 511, accessed Proquest; Advertisement 8, Harper’s Bazaar, Sep. 17, 1887, 20, 38 American Periodicals p. 655, accessed Proquest.

Cerealine was marketed to consumers as a food product with more nutrition, digestibility, value (“costing twenty cents, a cook in a private family of six persons, made puddings five times, waffles twice, muffins three times, griddle-cakes fived times; used “Cerealine Flakes” in soups…added some to six bakings of bread”), and ease of use (“it needs to be placed only in the tureen and have the hot soup poured over it before serving”) than any other grain product on the market for the duration of the product’s manufacture. Cerealine advertisements appeared in popular periodicals at that time.

Additionally, according to Gent’s patent for "new and useful improvements in the art of brewing malt liquors," Cerealine Flakes were intended to be marketed in bulk to brewing establishments as a replacement for boiled cornmeal that was mixed with malt and hops. The solubility of the flakes eliminated time-consuming boiling of cornmeal, a major step in the manufacture of beer and other alcoholic beverages.

[8] "May Take Their Plant to Chicago," Logansport Pharos Tribune, March 2, 1892, 1, Newspaper Archive; The Indiana Farmer, March 5, 1892, 8, col. 1; Cambridge City [IN] Tribune, March 24, 1892, 1, col. 1; Indianapolis of To-day (Indianapolis: Consolidated Illustrating Co., 1896), n.p.; Indianapolis Sanborn Map #61, 1898 and Indianapolis Sanborn Map #378, 1898 accessed Indianapolis Sanborn Map and Baist Atlas Collection; “New Machinery Purchased for Cummins Plant,” [Columbus, IN] Evening Republican, January 7, 1926, 1.

In 1892, Cerealine ended its Columbus milling operation and moved to Indianapolis. Some newspapers reported the move as a means to reduce costs by taking advantage of lower freight pricing available in the capital city. According to the contemporary factbook, Indianapolis of To-day, the new mill was located off North Indiana Avenue with offices located on-site along Gent Ave. and W. 18th. Sanborn maps corroborate the locations.

The Cerealine Mill in Columbus remained in operation under Benjamin C. Thomas (son of Richard Thomas, original partner). An image of Ben C. Thomas Grain can be found in Henry R. Fish’s Illustrated Columbus Indiana 1915. Cummins Engine Company, Inc. did business at the mill site after Thomas’s operations ceased.[9] "Running on Sunday, Too," Weekly Indiana State Journal, August 3, 1898, 8, 19th C. US Newspapers; Thirty-sixth Annual Report of the Indiana State Board of Agriculture, 1886 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1887), 322; Cerealine Manufacturing Company Sales Invoice, private collection of "R.E.R.," Dec. 7, 1886, accessed http://columbusin.proboards.com/thread/57/cerealine?page=2; "High Prices for Corn in Indiana," Elkhart Weekly Truth, March 36, 1891), 8, Newspaper Archive; Indianapolis of To-day (Indianapolis: Consolidated Illustrating Co., 1896), n.p.

By 1891, the company was processing up to 7,000 bushels of corn daily and paying the highest prices offered in the state for the commodity, according to contemporary newspaper articles. In 1886, Indiana produced 108,217,209 bushels of corn according to the Indiana State Board of Agriculture. Cerealine reported a 6,000 bushel/day capacity in that year on its sales invoices and in advertisements. By 1896, the company’s annual sales were reported by Indianapolis of To-day to be over $2 million, and by 1898, the Weekly Indiana State Journal reported the Cerealine mill was processing 12,000 bushels per day.

[10] Ralph L. Nelson, ed., “The First Merger Wave,” Merger Movements in American Industry, 1895-1956 (National Bureau of Economic Research, 1959): 71-105, accessed October 30, 2012, http://www.nber.org/chapters/c2527; Naomi R. Lamoreaux, “Industrial Organization and Market Behavior: The Great Merger Movement in American Industry,” Journal of Economic History 40, no. 1 (March 1980): 169-171, accessed JSTOR doi: 2120441; Philip Scranton, “Diversity in Diversity: Flexible Production and American Industrialization, 1880-1930,” The Business History Review 65, no. 1 (Spring 1991): 27-90, accessed JSTOR doi: 3116904.

Scholars disagree on the causes and effects of the first and second merger waves, but acknowledge the phenomenon of increased mergers following recessions. (See Nelson above.) The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression that took hold when two major railroads went bankrupt and affected industrial cities especially hard. For more information about the Panic of 1893, watch this Foundation for Economic Education lecture, or see Sean Cashman, America in the Gilded Age (New York: NYU Press, 1993).

[11] Indianapolis Sanborn Map #61, 1898 and Indianapolis Sanborn Map #378, 1898 accessed Indianapolis Sanborn Map and Baist Atlas Collection; "Form Big Trust," The Decatur [IL] Semi-Weekly Herald, Apr. 18, 1902, 3; “A Hominy Trust Formed,” New York Times, April 13, 1902, 1; “The Hominy Trust,” Indianapolis News, April 14, 1902; “Big Mortgage is Filed,” The Indianapolis Journal, April 25, 1902.

In 1902, the “heaviest manufacturers of corn goods” formed a conglomerate, American Hominy Company; the Cerealine Manufacturing Company plant in Indianapolis joined this company. Contemporary articles hint that Cerealine and the other mills that merged to form the company were the region’s largest, and suggest that the reason for the merger may have been financial—reducing overhead to each individual mill by consolidating administration and shipping. The New York Times, April 13, 1902, listed the ten “plants” involved: “Indianapolis Hominy Mills, Indianapolis; Cereal Manufacturing Company [Cerealine], Indianapolis; Hamburg Mills, Hamburg, Iowa; St Joseph Mills, St Joseph, Mo.; Shellabarger Mill and Elevator Company, Decatur Ill.; Pratt Cereal Mill Co., Decatur Ill.; Danville Mills, Danville, Ill.; Miami Maize Mills, Toledo, Ohio; Mount Vernon Mills, Mount Vernon, Ind.; Hudnut Mills, Terre Haute, Ind.” The Cerealine milling complex on Gent Ave. showed up as “American Hominy Mills” on Sanborn maps of Indianapolis as early as 1898.

[12] "Try a Good Thing at Our Risk," The Fort Wayne Daily News, Feb. 12, 1907, 8; Advertisement, Logansport Journal, February 26, 1907, 6; “Petitions for Closing of Columbus Firm's Business," Indianapolis Star, Dec. 7, 1910), 6; “To Retire $1,250,000 of Preferred Stock,” Indianapolis News, December 19, 1913, 29; “Hominy Plant Addditions,” Indianapolis News, August 5, 1920; “Buys Shelbyville Mills,” Indianapolis Star, May 18, 1923, 3; “Hominy Co. asks Receiver,” Indianapolis News, January 4, 1924, 5; “American Hominy Co. is Declared Bankrupt,” Indianapolis News, January 8, 1924, 3; “For Sale: Mills—Elevators—Equipment,” Indianapolis Star, February 17, 1924, 19; “Hominy Plant is Sold to New York Concern,” Indianapolis News, September 13, 1924, 1; Madison, Tradition and Change, 40-44.

In 1907, American Hominy Co. in Indianapolis was marketing “Toasted Cerealine Flakes” via Indiana newspapers. The company appeared to be prospering. In December 1918, the Indianapolis News reported that the American Hominy board of directors had voted to retire $1,250,000 of the company’s preferred stock and opined that this action “speaks of the growth of an industry started in Indiana.” In August 1920, the Indianapolis News described American Hominy Co. plans to spend $83,000 on additions to the Indianapolis plant on Gent Avenue. As late as 1923, the Indianapolis Star reported American Hominy’s purchase of two grain elevators in Shelbyville, Indiana.

But by January 1924, the Indianapolis News reported that the American Hominy Company was bankrupt. Company president George A. Chapman said that prohibition was responsible for the company’s demise: “Sixty per cent of our output formerly was sold to brewers. Thus far the company has been unable to replace the orders of the brewers.” An advertisement in the February 17, 1924 Indianapolis Star offered for sale “the properties and good will of the American Hominy Co.” in Iowa, Illinois, and Indiana. The Indianapolis plant was reported sold by the Indianapolis News, September 13, 1924.

Keywords

Business and Industry