The earliest report of African Americans living in what is now Indiana comes from a 1746 report on French settlements which states that forty white men and five black slaves lived in Vincennes on the Wabash River. Frenchmen living in the area continued to keep slaves throughout both the French and English occupations. After the American Revolution, the U.S. Congress adopted the Ordinance of 1787 to govern the new western territory. This Ordinance prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude in the Northwest Territory.

Many of the first white settlers in Indiana brought their slaves with them from slave states in the south. After Indiana Territory was formed in 1800, proslavery political leaders including Governor William Henry Harrison enacted laws evading the slavery prohibition in the Northwest Ordinance and restricting the rights of all blacks in the Territory.

By the time Indiana became a state, the antislavery faction had assumed political leadership. The 1816 Constitution clearly prohibited slavery and involuntary servitude. The effects of the 1816 Constitution and of Indiana Supreme Court rulings in favor of blacks over the next decades slowly eliminated slavery and indentured servitude in Indiana. Nothing was done however to restore civil rights to the growing black population in Indiana.

Blacks were not allowed to vote or to serve in the militia. They could not testify in court cases involving whites. Black children were not allowed to attend public schools. After 1831, black settlers in Indiana were required to register with county authorities and to post a $500 bond as a guarantee of good behavior.

Blacks moving to Indiana belonged to one of three groups: blacks who had been free or whose families had been free for a long time in their home states; recently freed slaves; and fugitive slaves. Increasing restrictions on the liberties of free blacks living in slave states and laws prohibiting recently freed slaves from remaining in slave states provided the motivation for many to make the dangerous trek from south to north. North Carolina, Virginia, and Kentucky provided most of Indiana's black settlers.

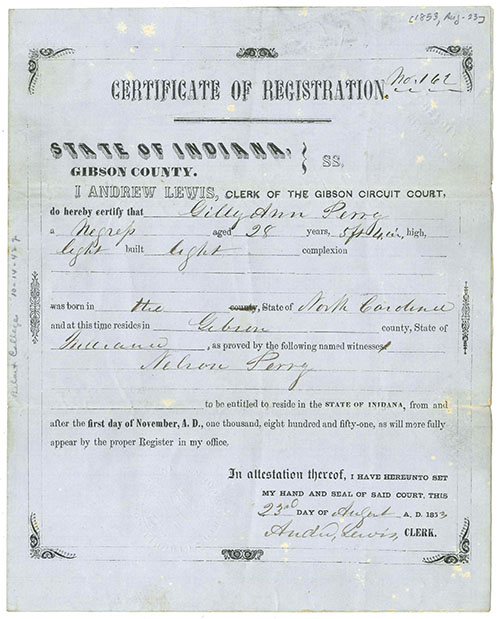

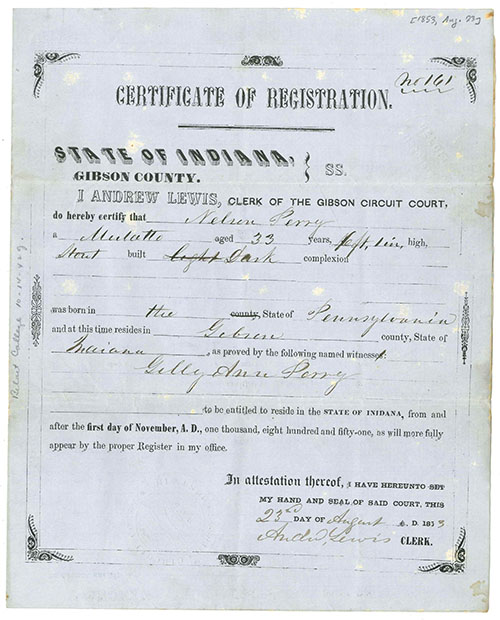

After the adoption of Article XIII of the 1851 Constitution, blacks living in Indiana were required to register themselves and their families with clerks of circuit courts. The document at right is a reproduction of a registration certificate issued in Gibson County, Indiana to Gilly Ann Perry. Some Indiana counties were more diligent than others in the registration of blacks. Many of these so-called Negro Registers are available in the Indiana State Archives.

The images above courtesy:

Indiana State Library, Nelson Perry Collection, S1906

At least thirty black farm communities were established, mostly in central and southern Indiana, between 1820 and 1850. Farming and farm labor were the most common occupations of blacks listed in the 1850 census. Others included barber, blacksmith, carpenter, plasterer, brickmason, whitewasher, shoemaker, cooper, teamster, cook, steward, waiter, and domestic servant. Many blacks moving to Indiana cities settled along the Ohio River where work in the river boat industry was available.

Because blacks were excluded from white society, including publicly funded schools, black settlers in Indiana established their own schools, churches, and social organizations.

Increasing tensions nationally between antislavery and slavery factions beginning in the late 1830s resulted in increasing prejudice against blacks. The culmination of this prejudice in Indiana was Article XIII of the Indiana Constitution of 1851, which stated that "No negro or mulatto shall come into, or settle in the State, after the adoption of this Constitution." Section 2 set fines for violations of the article, and Section 3 provided that money from fines be used to defray costs of sending blacks in Indiana to Liberia. Additional legislation required all blacks already living in Indiana to register with the clerk of the circuit court.

Sources: Thornbrough, Negro, 1, 32, 68, 142, 143, 151, 166-72; Vincent, xii, xiii.