PART III: “The Many Lives He has Led”

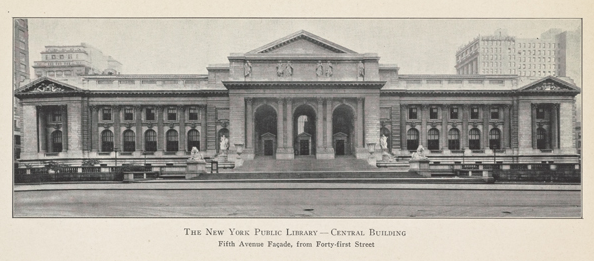

New York Public Library Central Building.

Image courtesy of “A Digitized History of the New York Public Library,” NYPL.org.

See Part II: “A New Era of Hospital Construction” for Billings’s work to establish the Johns Hopkins Hospital and reform the American medical system.

Billings’s hospital designs, which minimized the spread of disease, and his efforts to educate the public about hygiene are more relevant than ever, as the CDC struggles to combat the spread of Ebola and Enterovirus D68. Despite modern technology, educating the public about methods of contagion and effectively quarantining the ill remains an issue. We have, in large part, Billings to thank for many of the basic preventive measures in hospitals, particularly with the establishment of the Johns Hopkins Hospital.

Three decades after the Civil War, Billings lamented the inability of medical establishments to limit the spread of disease. In his 1893 “The Relations of Hospitals to Public Health,” Billings asserted that the “importance of hospitals for certain forms of contagious and infections disease, as a means of preventing the spread of such diseases, would appear to be almost self-evident, yet very few cities in this country are provided with them.” He emphasized the prevention of illness rather than solely its isolation, advocating for the move from “pest houses” that secluded ill patients, to better medical facilities.

Having served as a Civil War surgeon, Billings witnessed the rapid spread of illness and onset of infection among wounded soldiers. His effective medical administration on the battlefield helped convince Johns Hopkins trustees to appoint Billings the designer of a new Baltimore hospital for the indigent sick. Billings designed the Johns Hopkins Hospital specifically with preventative measures in mind, eliminating corners to prevent the buildup of dust and disease. His design also required visitors and staff to go outside to travel from one ward to another, ensuring that “foul air, in any forms, cannot spread from one building to another.” These and other preventative features were modeled by several other hospitals in the period. Billings encouraged hospitals to promote public health by “increasing and diffusing knowledge as to the causes, nature and best methods of prevention or treatment of disease.”

Billings served as director of the University of Pennsylvania Hospital and taught there as a professor of hygiene. He also advocated for sanitation reform by conducting and reporting on systematic sanitary surveys of diseases in the U.S., including yellow fever. According to A. McGehee Harvey’s and Susan L. Abrams’s 1989 “John Shaw Billings: Unsung Hero of Medicine at Johns Hopkins,” each of Billings’s reports represented “pioneer hygienic work, far ahead of its time, undertaken in a day when there were no uniform quarantine regulations in the United States.” Furthermore, Billings advanced public hygienic measures by joining the American Public Health Association in 1872 (becoming president in 1880) to “replace a system of sanitation based on individual opinion and hypothesis with one based on science.” By 1894, The (Washington, D.C.) Evening Star dubbed Billings the “foremost authority in the country in municipal hygiene and medical literature.”

Billings’s accomplishments were so varied and expansive that many remain overlooked today, despite their enduring national significance. For example, in 1896 Billings served as the first director of the New York Public Library (serving until his death in 1913), expanding its collections “without parallel.” He publicly recognized NYPL female employees and at a Women’s University Club meeting lamented that “most of the library work is done by women, and done splendidly, and it is a shame that they are not better paid.” Industrialist and philanthropist Andrew Carnegie solicited Billings’s help with the establishment of a system of branch libraries in New York City and referred to Billings on various educational matters. Additionally, Billings convinced Carnegie to donate millions of dollars to public libraries throughout the United States.

Billings also worked with the U.S. Census from 1880 to 1910 to develop vital statistics. He sought to record census data on cards using a hole punch system, which would allow the data to be counted mechanically. Herman Hollerith applied Billings’s concept, devising “‘electrical counting and integrating machines’” employed by the U.S. Census.

Billings passed away March 11, 1913 and was buried in the Arlington National Cemetery. At a meeting to honor Billings’s life at the Stuart Gallery of the New York Public Library, Andrew Carnegie contended “by his faithful administration of the great tasks committed to him he left the world better than he found it. I never knew a man of whom I could more safely say that.” The Evening Mail summarized the sentiments of many, including the author of this post, stating

“One gasps at the many lives he has led, the many appointments he has filled, and his gigantic work among libraries and hospitals.”

For more about Billings’s pioneering disease prevention work, as well as his many other accomplishments, see the corresponding Historical Marker Review and the National Medical Library’s extensive John Shaw Billings Bibliography.