PART II: “A New Era of Hospital Construction”

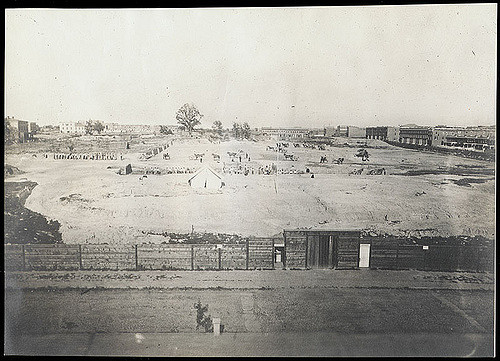

Ground being cleared for Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1877, photo courtesy of

Flickr’s Johns Hopkins Medical Archive’s photostream.

See Part I: “I Could Lie Down and Sleep for Sixteen Hours without Stopping” for biographical information about John Shaw Billings, his experience as a Civil War surgeon, and his innovatory Surgeon-General library’s Index Catalogue.

In his work to reform the post-Civil War medical system, Billings confronted many of the same problems that afflict the modern healthcare system. Whereas the current cost of a hospital stay is often prohibitive for those with fewer resources, hospitals in the mid- to late-1800 existed primarily to treat the poor; the wealthy were afforded house visits by doctors. In an 1893 address, Billings states “Forty years ago the number of hospital beds in our cities was very small in proportion to the population . . . and the demand for such accommodation was also small. People did not go to hospitals as they did in the homes of the people.” In both eras, however, issues of wealth and class influenced medical treatment.

Billings elaborated that after the Civil War people of all classes began to seek treatment in hospitals, as with the

increase of knowledge about hospitals and their capabilities has come an increased demand upon them for accommodation for persons in comfortable circumstances, who are affected with diseases which can be better treated in them than in private houses; in other words, for private rooms for pay patients, especially those requiring surgical, operations of suffering from certain forms of nervous disease.

The war revolutionized the American medical system as it required personnel to treat large numbers of severely wounded soldiers in rapid fashion. In addition to treatment problems, such as preventing infection, personnel struggled with administrative issues like locating and communicating with medical staff and procuring supplies. Adapting to these obstacles informed medical treatment in the post-war public health sphere. Billings contended in his address, “The war of 1861-1865, and the great influx of immigrants . . . taught us how to build and manage hospitals, so as to greatly lessen the evils which has previously been connected with them, and it also made the great mass of the people familiar with the appearance of, and work in, hospitals, as they had never been before.”

Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1889, the year of its opening. Photo courtesy of Flickr’s

Johns Hopkins Medical Archive’s photostream.

Billings’s “novel approach” to hospital administration and his field experience appealed to the trustees of Johns Hopkins’ fund, tasked with establishing a hospital for the “indigent sick.” After inviting five medical professionals to submit plans for the hospital, they selected Billings’s design in 1876. In their article “John Shaw Billings: Unsung Hero of Medicine at Johns Hopkins,” A. McGehee Harvey and Susan L. Abrams contend that it “was Billings the man, rather than his proposal” that convinced the trustees to appoint him to the task, as he was extremely knowledgeable about medical education, hygiene, and the “philosophical underpinnings” of hospital construction.

His essay to the trustees reflects his revolutionary ideas about medical treatment and education, asserting that a hospital should not only treat patients, but educate medical professionals. In that period, requirements to receive one’s medical degree were considerably low and medical education often failed to adequately prepare students to practice medicine. Billings sought to change this by wedding the hospital to the university, providing students with hands-on experience. He also sought to raise standards of medical education, so that a diploma ensured the physician could “learn to think and investigate for himself.”

In order to get ideas for the construction of Johns Hopkins Hospital, Billings inspected England’s hospitals. From 1876-1889, the period in which the hospital was constructed, he served as a medical adviser to the Hopkins trustees.

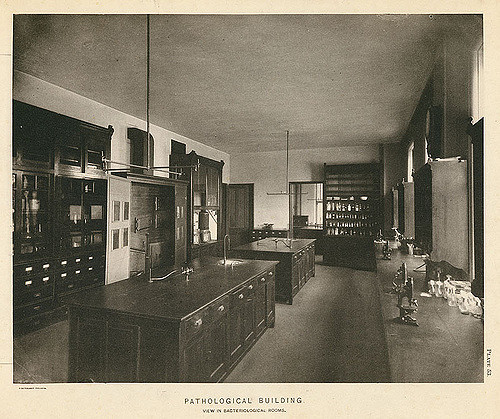

Pathological Building, Johns Hopkins Hospital, 1889. Photo courtesy of Flickr’s

Johns Hopkins Medical Archive’s photostream.

Opened in 1889, the Johns Hopkins Hospital included a training school for nurses, a pathological laboratory for experimental research, and connected to a building with a teaching amphitheater. In an address at the opening of the hospital, Billings stated that with the hospital he hoped to produce “investigators as well as practitioners” by having physicians “issue papers and reports giving accounts of advances in, and of new methods of acquiring knowledge, obtained in its wards and laboratories, and that thus all scientific men and all physicians shall share in the benefits of the work actually down within these walls.” He asserted that the sharing of one’s work through publications, done sporadically at the time, would aid in the education of physicians, help with diagnoses, and improve the medical system as a whole.

The Johns Hopkins Hospital raised the standards of medical education, treatment and sanitation and was modeled by other hospitals. Dr. William H. Welch, colleague and friend of Billings, summarized Billings’s vast contribution, contending that the Johns Hopkins Hospital “marked a new era in hospital construction . . . When one considers the influence of this hospital upon the construction of other hospitals . . . it is evident that Dr. Billings’ services in the field we are now considering were of large and enduring significance.”

In addition to revolutionizing hospital administration and design, Billings was an early advocate of what is referred to today as “bedside manner.” In his 1895 Suggestions to Hospitals and Asylum Visitors, he asked readers to consider “Is a spirit of kindness and gentleness apparent in the place? . . . Is the charitable work of the hospital performed in a charitable way? Do the physicians and nurses display that enthusiasm and esprit due corps which are essential to good hospital work?”

Starting to feel like your resume is a little insubstantial?

For more about Billings’s work to establish the Johns Hopkins Hospital, see the Historical Marker Review. Check back for Part III: “The Many Lives He Has Led” about Billings’s intensive efforts to reform public sanitation, as well as his other accomplishments, such as serving as the first director of the New York Public Library.