George W. Geib

Butler University

|

John Hunt Morgan’s 1863 cavalry raid was the largest military campaign conducted in Indiana during the Civil War. The raid was ordered by General Braxton Bragg, commanding the Confederate Army of Tennessee, to draw Union cavalry north into Kentucky; the intent was to impede an anticipated advance toward Chattanooga by the Union Army of the Cumberland commanded by Major General William S. Rosecrans. Morgan was a natural choice to command this raid, having conducted two similar cavalry operations in Kentucky in the past year. Without making his specific plans clear to his superiors, Morgan soon expanded both the size of his force and the target of its raid. Crossing the Cumberland River in Kentucky on July 2, and the Ohio River on July 8 and 9, he spent three weeks in Indiana and Ohio. One of his subordinates, Colonel Basil W. Duke, author of the postwar A History of Morgan’s Cavalry, provided much information about the Morgan’s motives and methods.

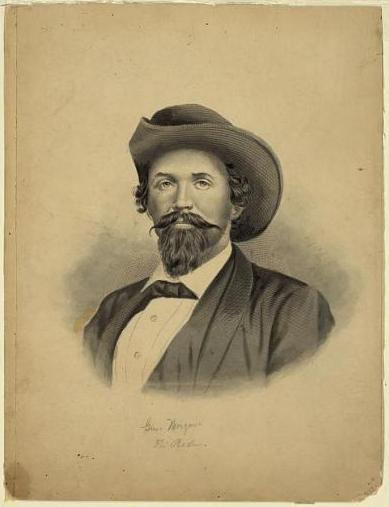

Confederate General John Hunt Morgan, 1825-1864 Source: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Online Catalog

The Confederates used two captured steamboats to cross the Ohio River, west of Louisville, from Brandenburg, Kentucky, to Mauckport, Indiana. Opposition from Indiana home guard units and two Union gunboats slowed, but did not stop, them. Once in Indiana, the raiders spent five days riding east to the Ohio border. Morgan, and his midwestern victims, often exaggerated the size of the raiding force; modern estimates suggest about 2,100 effectives. The force included eight regiments of Kentucky cavalry, one of Tennessee cavalry, two howitzers, and two Parrott guns. Morgan’s colorful reputation had attracted youthful recruits from states as far away as Texas; many were drawn from family groups and tightly knit small communities. Four of Morgan’s brothers joined him; one died in an early skirmish.

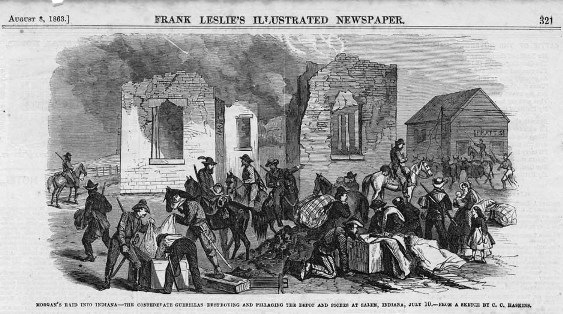

Small groups of Morgan’s scouts and raiding parties rode through a number of southern Indiana counties. The main body of Morgan’s force followed a route through eight of those counties passing through such towns as Corydon, Salem, Lexington, Vernon, and Versailles on the way to Harrison, Ohio. When sufferers later filed claims for the destruction and looting from the raid, the bills suggested Morgan focused upon four targets: railway offices, bridges and other properties; merchandise from local stores; ransoms paid to avoid the burning of mills and other industrial properties; and horses to replace his exhausted mounts. Civilians complained most frequently about food requisitioning. Civilian killings and home burnings did occur, the most remembered of those was possibly the death of the Reverend Peter Glenn south of Corydon who was slain in retaliation for shots allegedly fired from his home.

Morgan’s Raid into Indiana, July 10, 1863 at Salem, in Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. Source: Indiana Historical Society, P0455.

Responsibility for the defense of Indiana rested upon three military forces: the Federal Army’s Department of the Ohio, Union naval gunboats on the Ohio River, and the Indiana Legion, or state militia. The Department of the Ohio commander was Major General Ambrose E. Burnside; he was based in Cincinnati but was under War Department orders to carry the war down into eastern Tennessee. Naval forces, under Lieutenant Commander Leroy Fitch, were expected to patrol the Ohio River and prevent crossings. Governor Oliver P. Morton commanded the Indiana Legion; coordination—much of it by telegraph and staff rider—proved difficult, and Morgan sought to increase that difficulty by misinformation and misdirection.

Federal forces made their main contribution with a large cavalry force led by General Edward Henry Hobson, who conducted an aggressive pursuit. In addition to the Union gunboats that shelled Morgan’s initial crossing, other gunboats later helped to prevent him from returning across the Ohio River to West Virginia. General Burnside initially sought to defend larger cities, such as Cincinnati, and to protect camps and supplies. He eventually assembled a field force that engaged Morgan in southeastern Ohio at Buffington Island, dispersing and ultimately capturing the raiding force.

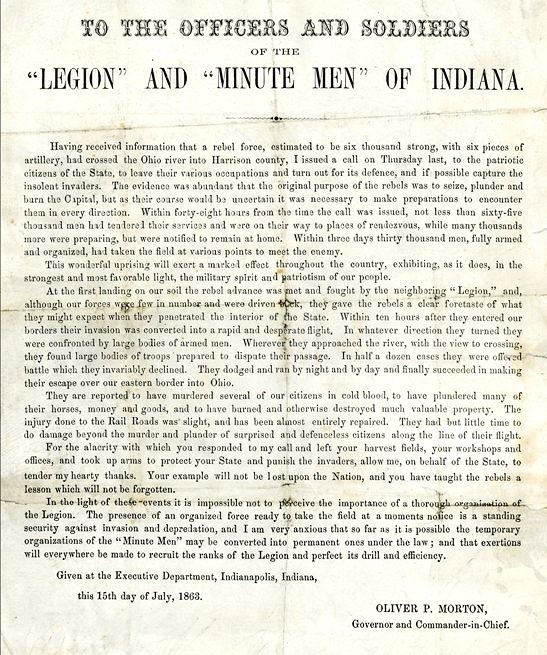

Governor Morton and state military commanders contributed to the defense by raising many companies of men throughout the southern half of the state, and by hurrying them, often by rail, to Morgan’s likely targets. Estimates of militia turnouts range as high as 65,000 during the raid. Far better organized than at the time of Johnson’s Newburgh Raid in 1862, the Indiana militia showed a willingness to fight if not always a high level of training. Generally, the militia commanders sought to place their men in defensible positions; Colonel H. T. Williams was especially adept while defending Vernon, Jennings County. Other, often smaller, forces were less successful. Morgan captured and paroled several units; the largest was approximately 300 poorly deployed men at Versailles, Ripley County. Small numbers of militia often contributed by cutting trees and creating roadblocks and other defenses. One actual battle occurred on July 9 at Corydon, Harrison County. There approximately 400 Indiana infantry sought to defend a hastily constructed line of abates—formed by felled trees with sharpened branches—south of the town. The force initially delayed the Confederate advance, but it was eventually flanked; the soldiers were captured and paroled.

Morgan brought the manners and style of a romantic cavalier to his actions, attracting much attention to himself then and now. His effectiveness may, however, be questioned. He was not as successful as some other raiders of 1863, such as Union Colonel Benjamin Grierson in Mississippi, in severing lines of communication. No major Indiana city was occupied, despite the temptations presented by New Albany, Floyd County supply depots or Indianapolis’ prisoner of war camps. No railroad was closed for more than a short time, and little evidence exists to suggest Morgan’s destruction caused more than inconvenience in the movement of Union soldiers or military shipments. The raid did produce initial civilian fears, but those fears were usually expressed in outpourings of Union sentiment. No Copperhead uprising took place, and no recruits flocked to Morgan. Despite the initial urging of General Burnside, it did not prove necessary for Union authorities to impose martial law and suspend habeas corpus. General Burnside’s army did move slowly in those weeks, but such caution was characteristic of his 1863 command style. In the end, two brigades of good Confederate cavalry were captured or dispersed, and Union movements in Kentucky were less hindered thereafter. Morgan’s raid was a dramatic campaign and a Confederate defeat.

On July 15, 1863, Governor Oliver P. Morgan issued a statement to the citizens of Indiana thanking them for their response to the defense of the state during the recent raid by Confederate John Hunt Morgan. Source: Broadside, Manuscripts and Rare Books, Indiana State Library.

Bibliography:

Duke , Basil W. A History of Morgan’s Cavalry. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1960. Reprint of the original printed by the Miami Printing and Publishing Company, Cincinnati, Ohio.

Horwitz, Lester V. The Longest Raid of the Civil War: Little-Known & Untold Stories of Morgan’s Raid into Kentucky, Indiana & Ohio. Cincinnati, Ohio: Farmcourt Publishing, Inc., 1999, rev. ed. 2001.

Mackey, Robert R. The Uncivil War, Irregular Warfare in the Upper South, 1861-1865. Norman, Okla.: University of Oklahoma Press, 2004.

Resources for Educators

Morgan's Raid game, produced by Ball State University. Java-based game for 4th grade, appropriate for all audiences.