Santa Claus vs. Santa Claus

Above: Cover of Appellate Court Brief

Likely holding the record for the number of times the name “Santa Claus” appears in the title of a legal case, the story of Santa Claus v. Santa Claus started in 1856 when the town of Santa Fe was set to get its first Post Office. Their first application was rejected, as there was already a Santa Fe, Indiana in Miami County. Stories vary on how they settled on the name Santa Claus instead, ranging from magical to mundane, but in any case, the second application was accepted. While the town was still referred to as Santa Fe locally, the post office started receiving mail from across the country, addressed to the office’s namesake.

In 1914 the local postmaster, James Martin, took it upon himself to start answering the letters, encouraging even more correspondence. The post office’s fame exploded in the 1920s, when the Postmaster General declared that there would never be another Santa Claus post office in the U.S. due to the logistical problems caused by its holiday mailing and “re-mailing”; the process of sending packages and letters to Indiana so that they could be forwarded through Santa Claus and receive the coveted Santa Claus postmark. It gained even more notoriety when it and Martin were covered by Ripley’s Believe it or Not! in 1929. So much so that the USPS considered changing the name in the 1930s to avoid the holiday chaos. At its peak, the office managed almost 3 million letters to Santa!

With this level of fame, it wouldn’t be long until people started attempting to monetize the town’s connection to the magical old elf. One of the first of these men was Vincennes entrepreneur Milton Harris, who worked with James Martin to open Santa’s Candy Castle in 1935. Harris’s vision was that Santa Claus would be turned into an ideal Christmas village where toys and candy would be made and given freely, sponsored by various corporations. He followed up the Candy Castle with Santa’s Workshop and Toy Village and secured a lease from the Reinke family on 31 nearby acres for future expansion of Santa-related attractions.

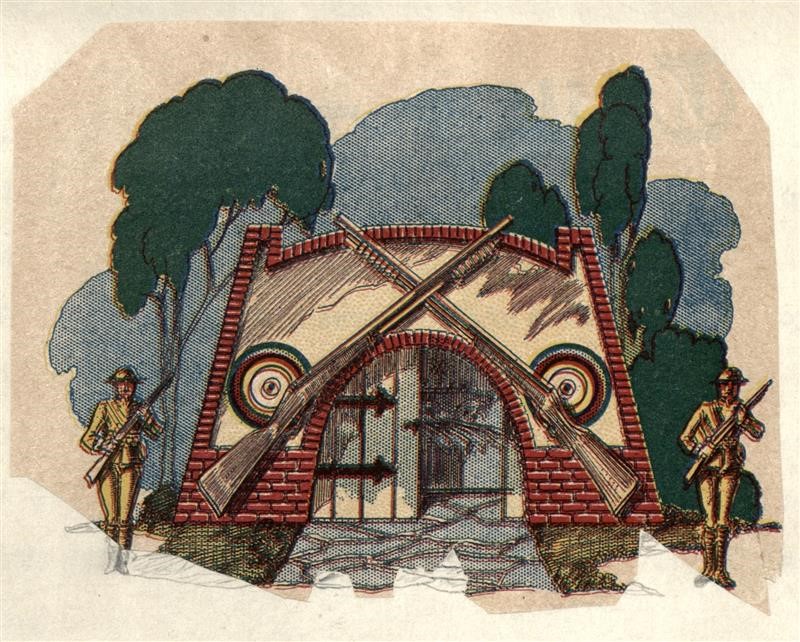

Above: Concept art for Harris’s Lionel Train Depot, Wyandotte Pavilion, and Daisy Air Rifles Barracks.

However, Carl Barrett, President of the Illinois Automobile Club, was hot on his heels. Just 4 months after Harris leased the land from the Reinkes, Barrett came to Santa Claus and purchased the very same land that had been leased to Harris. As Harris had a head start on a full-fledged attraction, Barrett rushed to put up a giant statue of Santa Claus, eventually unveiling the piece on the same day Harris opened the Candy Castle. Barrett insisted that he had come to rescue the town from the materialism of Harris but established himself as unreliable by insisting that his granite statue was blessed by a fallen meteor just before the dedication. In reality, the statue was cement, and degraded quickly, and the crater nearby was just a plain old hole that Barrett threw some metal into to sell the myth. This statue, and further actions by Barrett & Harris’s attempts to stop them would be what eventually landed Santa Claus in front of the Indiana Supreme Court.

Above: December 23, 1935 Unveiling of Santa statue

Milton Harris and Carl Barrett unveiled their competing attractions on December 22, 1935. However, at this point the two men had already been fighting one another in court since November, when Harris filed a complaint in the Spencer County Court. Harris’s primary complaint was that Barrett, and his associates were not honoring the terms of the lease that Harris had signed with the Reinkes. The key passage of the lease reads:

“It is agreed and understood by the parties that the second party (Harris) shall have the exclusive right during the term of this lease to conduct on said real estate any and all business having any relation to the Santa Claus idea”

For his part, Barrett and his associates appear to have never taken the lease seriously, telling the Reinkes when he purchased the land that it “didn’t amount to anything.” However, the Martin Court, where the case was eventually moved to, disagreed with his assessment and upheld Harris’s lease in November of 1936. The court also awarded Harris $5,100 in damages. Most surprisingly, the Martin Court went so far as to quiet Barrett’s title to the land, effectively giving ownership of it to Harris for at least the next 25 years.

In the county court Barret’s primary argument was that Harris’s “Santa Claus of Santa Claus, Inc.” had been incorporated after Barrett’s “Santa Claus, Inc.” and that Harris’ incorporation should not have been accepted and was invalid as it was confusingly similar. However, both the county shot this argument down quickly, stating that the Indiana Secretary of State was given the quasi-legal authority to determine when a corporate entity’s name was too similar to another and that the courts had no ability to alter that decision.

Barret’s team immediately began the appeal process, but the case was denied by that Court in October of 1939 on grounds of both an adequate judgment from the Martin Court and procedural errors on behalf of the team. The Appellate Court was also concerned with what was either gross incompetence or willful obstruction on the part of Barrett’s group stating regarding one point of contention:

“the record has been mutilated, changed, and forged to show that a written praecipe was filed whereas the clerk’s return to the writ of certiorari shows that no such written paecipe was ever given to him”

Either undeterred or desperate, Barret requested a transfer to the Supreme Court, which was granted, finally appearing before the court in May of 1940. In a somewhat surprising reversal, Harris’s damages were significantly reduced and the action to quiet Barrett’s title to the land was overruled. However, Barrett was still forced to honor Harris’s lease and would be subject to future damages if he continued to pursue the business of Santa Claus in Santa Claus.

Carl Barrett had “won” in the Indiana Supreme Court and had his damages reduced. However, he was still worse off than he was before the case. He would face off with Harris in court again after acquiring some of his competitor’s stock and demanding either a promise of profitability or a dissolution of Harris’s leases. He was once again unsuccessful. Barrett would continue to promote his statue, the village, and future attractions such as a 22-story cross and genuine Alaskan totem pole through the 1940s. However, the statue and its surrounding park, featuring a wishing well and small log cabin, were the only things of significance he ever actually completed.

Things started to look up for Barrett in 1938, when oil was discovered in the area. As opposed to Harris’s leases, which gave him no rights to extract oil, Barrett had purchased land outright and had such rights. While Barrett doesn’t appear to have accumulated a huge amount of oil wealth, he did live a comfortable life running the Rush Creek Oil Company out of New Harmony until his retirement. By 1954 newspapers noted that the Santa Claus statue and the park sat in a state of abandonment and disrepair, indicating that Barrett had moved on to more profitable interests. He died in Evansville in 1978.

Above: Santa Claus in Santa Claus Land, Santa Claus, IN, 1950

While Harris was successful in enforcing his lease, it never really paid off for him. He struggled to secure sponsors for his attractions other than Curtiss, and only ever completed a small toy shop and workshop aside from the Candy Castle. With the U.S. entry into the war coming shortly after the resolution of the Supreme Court case, Harris never had an unobstructed chance to make his ambitious dream a reality. After the war he would find himself once again attempting to enforce his position as the controller of Santa Claus business in Santa Claus, this time against Louis J. Koch. Unfortunately, he would not prevail, and died in Vincennes in 1950.

In 1946 Louis Koch of Evansville opened a toy factory on the outskirts of town. Shortly after it was built the USPS opened bids to relocate the overflowing post office, still in the small village of Santa Fe. Koch won the bid over Harris’s protests, relocating the post office outside the town and almost a mile away from Barrett’s statue and Harris’s castle, into the center of his newly built Santa Claus Land. Koch also found that since the town had never officially changed its name, he was free to organize his unincorporated area on the outskirts of the village as the first, 100% official, Santa Claus, IN. With a healthy initial investment and the securing of the all-important name and post office, Santa Claus Land would expand rapidly in the post-war era, and would eventually rebrand as Holiday World in 1984.