Graves et al v Indiana

Location: Memorial Park, Corner of SR 15 and SR 120, Bristol (Elkhart County, Indiana)

Installed: 2007 Indiana Historical Bureau Division of Historic Preservation Archaeology IDNR Elkhart County Historical Society and Robert Weed Plywood Corporation

ID# : 20.2007.1

Text

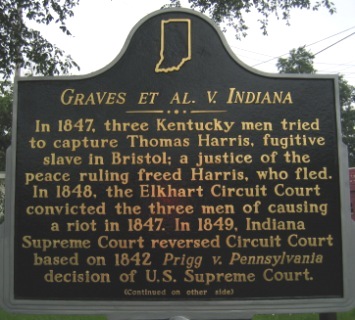

Side one:

In 1847, three Kentucky men tried to capture Thomas Harris, fugitive slave in Bristol; a justice of the peace ruling freed Harris, who fled. In 1848, the Elkhart Circuit Court convicted the three men of causing a riot in 1847. In 1849, Indiana Supreme Court reversed Circuit Court based on 1842 Prigg v. Pennsylvania decision of U.S. Supreme Court.

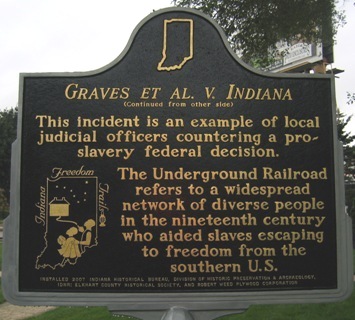

Side two:

This incident is an example of local judicial officers countering a pro-slavery federal decision. The Underground Railroad refers to a widespread network of diverse people in the nineteenth century who aided slaves escaping to freedom from the southern U.S.

Keywords

African American, Underground Railroad

Annotated Text

Side one:

In 1847, three Kentucky men tried to capture Thomas Harris, fugitive slave in Bristol; (2) a justice of the peace ruling freed Harris, who fled. (3) In 1848, the Elkhart Circuit Court convicted the three men of causing a riot in 1847. (4) In 1849, Indiana Supreme Court reversed Circuit Court based on 1842 Prigg v. Pennsylvania decision of U.S. Supreme Court. (5)

Side two:

This incident is an example of local judicial officers countering a pro-slavery federal decision. (6) The Underground Railroad refers to a widespread network of diverse people in the nineteenth century who aided slaves escaping to freedom from the southern U.S.

Notes

(1) The full name of this appeal to the Indiana Supreme Court was Joseph A. Graves, Elisha W. Coleman, Hugh P. Longmore v. the State of Indiana [1 Indiana 258 (1850)], Indiana Supreme Court, June Term 1849, Indiana State Archives, photocopy of handwritten transcript of the proceedings and judgment of Indiana v. Graves et al. in Elkhart Circuit Court, April Term 1848. Hereafter cited as Transcript in the notes that follow (B050635).

(2) Transcript, pp. [2, 5, 10-11] (B050635).

In an unpublished paper [Jeanne S. Miller, "The Slave Catcher Trial in Elkhart County, Indiana" (December 1997), pp. 1-2, 31 (B050634).] sent by the applicant, the author provided some information about Graves, Coleman, Longmore, and Judson. Miller's information has not been verified. Graves was from Boone Co., Kentucky, and, in 1846, he owned 10 slaves over the age of 16. In 1847, Graves owned 6 slaves over the age of 16. Miller cited Kentucky Tax Lists for 1846 and 47 for this information. Coleman and Longmore were from Kenton County, adjacent to Boone County Kentucky. Miller, pp. 1-2, 31 (B050634).

S. P. Judson is listed in the 1840 census in St. Joseph County Indiana. His large family included a free, black woman between the ages of 10 and 24. U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1840, Schedule 1, Population, St. Joseph County Indiana, p. 76, http://ancestrylibrary.com/ (accessed October 23, 2006) (B051009).

Judson hired Thomas Harris, a black man, in November 1846 to work for him for $10 per month. Harris had escaped from his Kentucky master in September 1846. Transcript, pp. [6, 10] (B050635). Harris was recommended to Judson by Wright Modlin, Cass County, Michigan. Modlin (also Maudlin) was also involved in Norris v. Newton, an 1849 fugitive slave case in South Bend. Miller, p. 27 (B050634).

Judson died of cholera June 16, 1849 near Ft. Laramie, Indian Territory, on his way to California as president of the Bristol California Mining and Trading Association. His obituary stated that Judson was the "proprietor of the Town" and had been associated with Bristol since 1841. Goshen Democrat, August 15, 1849, p. 2, c. 5 (B050828).

(3) Transcript, pp. [11-12] (B050635).

Indiana law specified that persons having claims to fugitives from labor must make an affidavit before the clerk of any circuit court in the state. The clerk would issue a warrant authorizing the arrest of the fugitive, and the presentation of the fugitive before some justice of the peace or judge of circuit court etc. to determine the case. Indiana Laws, 1843, pp. 1032-33 (B051011). In this case, justice of the peace David W. Gray dismissed the claim of Kentuckian Joseph A. Graves as "insufficient" because the warrant was signed by a justice of the peace rather than the clerk of the circuit court.

St. Joseph Valley Register, August 27, 1847 stated the following about the "runaway" found at Judson's in Bristol: "the negro was released, and departed for some other region." (B050017).

(4) Transcript, pp. [3-5] (B050635).

The judge instructed the jury that the warrant for Harris's arrest from the justice of the peace was "without authority." He stated that the defendants could not lawfully take Thomas without a valid Indiana warrant unless they did so "peaceably." The question for the jury was did the defendants cause a "riot" in taking Thomas Harris. The defense attorney argued that federal law regarding fugitive slaves superseded state laws based on an 1842 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Prigg v. Pennsylvania.

The Prigg decision was the first interpretation of the fugitive slave clause of the U.S. Constitution by the U.S. Supreme Court. The court ruled that slavery was protected by the U.S. Constitution; that the Fugitive Slave Act of 1793 was constitutional; that state laws interfering with the return of fugitive slaves were unconstitutional (null and void); and that slave owners or their agents could return alleged fugitives to slavery without any oral testimony or written affidavit, thus exposing any African American to kidnapping without legal recourse. The court decision also gave states the right to refuse to enforce the federal fugitive slave law. Interpretations of the decision provided other widely used avenues for anti-slavery and pro-slavery advocates. Paul Finkelman, "Prigg v. Pennsylvania and Northern State Courts: Anti-Slavery Use of a Pro-Slavery Decision, " Civil War History, 25, no. 1 (March 1979): 5-6, 8-10, 13-15, 21, 25-27 (B050633).

Indiana laws regarding fugitive slaves at first were concerned with the prevention of "manstealing, " the kidnapping of free African-American residents. As the issue of recapture of fugitive slaves became more heated, the Indiana General Assembly attempted to placate Kentucky slave owners while, in theory at least, continuing to provide a jury trial for alleged fugitive slaves. However, after the Prigg decision, the 1843 Indiana law concerning "any one owing service in any state or territory within the United States" provided no protection for an alleged fugitive or a free African-American resident. In 1846, a committee of the Indiana House of Representatives reported that based on the U.S. Supreme Court's decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, federal laws probably superseded even the 1843 Indiana law on fugitive slaves. Emma Lou Thornbrough, "Indiana and Fugitive Slave Legislation, " Indiana Magazine of History, 50 (September 1954): 214-19 (B00701).

(5) Transcript, p. [18] (B050635); Thomas L. Smith, Reports of Cases in the Supreme Court of Indiana (New Albany, 1850), p. 258, 261 (B050834).

There are a couple of discrepancies between this Smith edition of Reports of Cases and Horace E. Carter, 2nd ed., with annotations by Edwin A. Davis, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of the State of Indiana (Indianapolis, 1870), pp. 368-72 (B050636). Smith stated that the fines assessed Graves et al. were $130 apiece. The Carter, 2nd ed., (p. 368) stated that the fines were $30 apiece. The Transcript (pp. 3-5) stated that the defendants were fined $130 each. Smith stated that the judgment was "reversed, &c." Carter (p. 372) stated that the judgment was reversed, and "Cause remanded for a new trial." The Transcript (p. 18) noted that the judgment was reversed. In addition, the Indiana Journal, June 11, 1849, (p. 3, c. 2) listed the decisions of the Indiana Supreme Court (B050836). For Graves v. State, only "Reversed" was recorded.

(6) In his article, "Prigg v. Pennsylvania and Northern State Courts: Anti-Slavery Use of a Pro-Slavery Decision" Civil War History (March 1979), pp. 22, 33, Paul Finkelman stated that the U.S. Supreme Court decision in Prigg v. Pennsylvania, individual states' anti-slavery interpretations of that decision, and state and local officials' refusals to help owners return slaves to service brought about the 1850 Fugitive Slave Act. In the decisions of this case involving Graves, Coleman, and Longmore, we cannot determine the motives or intentions of the public officials involved.

However, the justice of the peace who dismissed the slave owner's arrest warrant permitted an alleged slave to go free. Transcript, pp. [11-12] (B050635). The Elkhart Circuit Court interpreted a part of the Prigg v. Pennsylvania decision in its instructions to the jury in such a way that three Kentucky men were convicted of the charge of Riot -- an anti-slavery use of Prigg. Transcript, pp. [3-4] (B050635); Finkelman, pp. 22, 33 (B050633). The Indiana Supreme Court decision -- a pro-slavery decision -- reversed the Elkhart conviction stating that Indiana laws regarding fugitive slavers were superseded by federal law. Smith, pp. 258, 259-60 (B050834). This same reasoning was later applied to Donnell v. State (1852) when the Indiana Supreme Court reversed the conviction of an anti-slavery advocate for assisting a slave to escape. Albert G. Porter, Reports of Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Court of Judicature of the State of Indiana, 5 vols. (Indianapolis, 1853), 3:480-81 (B051041).