Samuel M. Ralston

Location: 104 E. Washington St., Lebanon (Boone County, Indiana) 46052

Installed 2018 Indiana Historical Bureau, Boone County Bar Association, and Boone County Commissioners

ID#: 06.2018.1

![]() Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn about Ralston's ties, or lack thereof, to the Ku Klux Klan.

Visit the Indiana History Blog to learn about Ralston's ties, or lack thereof, to the Ku Klux Klan.

Text

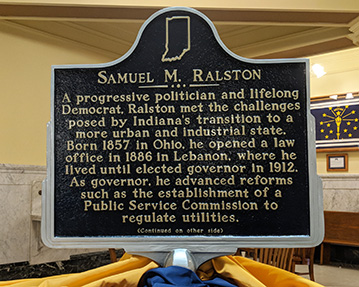

Samuel M. Ralston

Side One

A progressive politician and lifelong Democrat, Ralston met the challenges posed by Indiana’s transition to a more urban and industrial state. Born 1857 in Ohio, he opened a law office in 1886 in Lebanon, where he lived until elected governor in 1912. As governor, he advanced reforms such as the establishment of a Public Service Commission to regulate utilities.

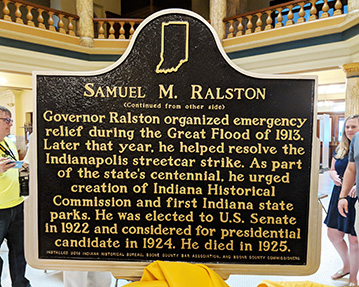

Side Two

Governor Ralston organized emergency relief during the Great Flood of 1913. Later that year, he helped resolve the Indianapolis streetcar strike. As part of the state’s centennial, he urged creation of Indiana Historical Commission and first Indiana state parks. He was elected to U.S. Senate in 1922 and considered for presidential candidate in 1924. He died in 1925.

Annotated Text

Samuel M. Ralston

Side One

A progressive politician[1] and lifelong Democrat,[2] Ralston met the challenges posed by Indiana’s transition to a more urban and industrial state.[3] Born 1857 in Ohio,[4] he opened a law office in 1886 in Lebanon,[5] where he lived until elected governor in 1912.[6] As governor, he advanced reforms such as the establishment of a Public Service Commission to regulate utilities.[7]

Side Two

Governor Ralston organized emergency relief during the Great Flood of 1913.[8] Later that year, he helped resolve the Indianapolis streetcar strike.[9] As part of the state’s centennial, he urged creation of Indiana Historical Commission [10] and first Indiana state parks.[11] He was elected to U.S. Senate in 1922[12] and considered for presidential candidate in 1924.[13] He died in 1925.[14]

Note: The citation “Hoy, page number” refers to Suellen M. Hoy’s Indiana University Ph. D. dissertation unless otherwise noted.

[1] “Suffrage Sessions to open Today; Prominent Women Are on Program,” Indianapolis Star, March 7, 1915, 1, Newspapers.com; Gilbert H. Hendren, “Efficient and Wise Executive: Governor Ralston’s Record One of Achievement,” Greencastle Herald, June 22, 1915, 3, Hoosier State Chronicles; Willis S. Thompson, “Political Gossip,” Greencastle Herald, November 24, 1915, 2, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Franchise League to Seek Full Suffrage,” Indianapolis News, December 5, 1916, 7, Newspapers.com; Clifton J. Phillips, Indiana in Transition: The Emergence of An Industrial Commonwealth: 1880-1920 (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau and Indiana Historical Society, 1968), 113-129; Suellen M. Hoy, “Governor Samuel Ralston and Indiana’s Centennial Celebration,” Indiana Magazine of History 71:3 (September 1975), 2-3, footnote 3, 235accessed Indiana Magazine of History Online; Suellen M. Hoy, “Samuel M. Ralston: Progressive Governor, 1913-1917,” PhD Dissertation, April 1975, Department of History, Indiana University, 235-236; James H. Madison, Hoosiers: A New History of Indiana (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana University Press, 2014), 221. [For the “conservatively progressive” quote Hoy cites: Ralston to Thomas Taggart, February 14, 1914, Ralston Papers.]

During the 1912 election, Ralston took a more progressive stance than the rest of the Democratic platform, partly to defeat his opponent who represented the Progressive party. According to Suellen M. Hoy in her Indiana University Pd.D. dissertation, Ralston’s publically declared progressive measures included: women’s suffrage, workmen’s compensation, better roads, improved vocational education, a child labor law, and a public utilities law, among other issues. In a 1914 letter, Ralston referred to his fellow Hoosiers as “conservatively progressive.” However, in his book Hoosiers, historian James Madison explains that the label is an equally fitting description of Ralston’s governorship.

During Ralston’s term as governor, almost all of the measures advocated by Progressives became law. This included acts which made progressive reform related to penal farms, public utilities, tenement housing, worker compensation, and good roads, among other initiatives. There are also many contemporary examples of Ralston being described as a progressive leader in Indiana newspapers. For example, in 1914 the Richmond Palladium-Item reported that Judge Thomas Duncan, Chairman of the Public Service Commission, “praised the record of the Ralston administration.” The article continued: “He said the Democratic legislature of 1913 had enacted more progressive legislation than any other assemblies in a decade.” Duncan cited the vocational education law, the public service commission law, and the fire marshal law among important reforms. Indianapolis newspapers show that Ralston attended and spoke at women’s suffrage meetings and advocated of a constitutional convention to address the extension of the vote to women, among other issues.

In 1915, State Examiner Gilbert H. Hendren described Ralston’s administration to the Greencastle Herald as progressive and yet moderate. Hendren wrote of Ralston: “Although his administration has more truly progressive legislation to its credit than any other previous administration, he has never been known as an extremist, nor has he advocated any cure-all legislation.” Also in 1915, Indiana Attorney General Evan B. Stotsenburg referred to the “truly progressive laws” enacted under Ralston. The Greencastle Herald printed a summary of remarks by Stotsenburg: “Under Governor Ralston and his official associates the democrats have not only been liberal in their promises of reforms but have been just as lavish in giving all and more than promised.” The Herald continued, “He spoke especially of the forward step taken by the democratic legislature, under the direction of Governor Ralston, in the interest of good business and humanity, when proper provision was made for the support of the educational, benevolent and correction state institutions.”

For a summary of Ralston’s work in pushing the General Assembly to approve more progressive reform measures, see: Phillips, 119-121. Ralston considered the Public Service Commission one of his most important accomplishments. See note 7 for more information.

[2] “Matson’s Gloom,” Greencastle Banner, Jun 10, 1886, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “The Candidacy of Theo. P. Davis,” Hamilton County Democrat,” August 19, 1892, 7, Newspapers.com; “For Secretary of State,” Indianapolis News, June 24, 1896, 10, Newspapers.com; “The Ticket,” Jackson County Banner, July 2, 1896, 4, Newspapers.com; Hamilton County Democrat, June 3, 1898, 4, Newspapers.com; “State Democrats,” Indianapolis News, June 22, 1898, 1, Newspapers.com; Hoy, 6-10.

Ralston became active in the Indiana Democratic Party at an early age, but was not elected to an office until 1913, mainly because the party had little power to win elections before that time. At Central Normal College in Danville, Ralston became active in a Democratic student club that debated the Republican club. As early as 1886, just two years after he graduated, the Greencastle Banner reported that he spoke at a Democratic nominating convention in Indianapolis. Referring to his speech in opposition to one of the nominees, the newspaper wrote: “Among the opposition were several tonguey fellows. The chief one being Samuel Ralston, of Owen County, who proved to be a sport of linguistic cyclone.” He first ran for a joint Indiana Senate seat (Boone, Montgomery, and Clinton counties) in 1888, but Republicans swept the election.

In 1892, Ralston came to the attention of Democratic political boss Thomas Taggart who made him a speaker for the Democratic Party and rewarded him by honoring him as a presidential elector. Ralston spoke at Democratic conventions throughout the state. In 1896, he won his party’s nomination for Secretary of State. The Jackson County Banner reported: “The Hon. Samuel M. Ralston of Lebanon, candidate for secretary of state, is a self-made man , and he made a good job of it . . . He has always taken a great interest in political work, and has been an especially warm advocate of the democratic party in this state.” The Hamilton County Democrat referred to him as “a recognized leader and a speaker of marked ability . . . always found advocating the true principles of democracy.”

For information about his elected offices see footnotes 6 and 11.

[3] Hoy, 1; Phillips, 271-385.

The thesis of Hoy’s dissertation is Ralston’s leadership during Indiana’s transition from a rural and agrarian to urban and industrial state. She explains:

During his administration, he earned the respect of most Indianans and acquired an enduring reputation as a progressive and as a champion of governmental economy. By initiating reform programs which brought Indiana into the forefront of progressive states, Ralston successfully governed a commonwealth that was rapidly being transformed from a predominately rural-agricultural society to a primarily urban-industrial society.

For more on this transformation see chapters seven through nine of Indiana in Transition. Phillips thoroughly describes Indiana’s “rapid transformation . . . from a predominately rural agrarian order into an increasingly urban, industrial society.” [p. 361] For examples of how he met the challenges of this transformation see footnotes 8 and 9.

[4] 1860 United States Census (Schedule 1), Warren, Tuscarawas County, Ohio, Roll M653_1043, page 397, Line 21, July 21, 1860, National Archives and Records Administration, accessed AncestryLibrary.com; Passport Application, Samuel M. Ralston, August 12, 1920, Certificate 80770, Roll 1332, U.S. Passport Applications, 1795-1935, National Archives and Records Administration, accessed Ancestry Library.

According to the 1860 United States Census (and confirmed by his passport and death certificates), Samuel Moffett Ralston was born December 1, 1857 in Tuscarawas County, Ohio, to John and Sarah Ralston.

[5] “For Secretary of State,” Indianapolis News, June 24, 1896, 10, Newspapers.com; “State Democrats,” Indianapolis News, June 22, 1898, 1, Newspapers.com; Hoy, 9. [Hoy cites: Meredith Nicholson, “Ralston of Indiana,” Ralston Papers; Lebanon Patriot, August 10, 1898; Sturdevant (a former classmate) to Ralston, March 10, 1887, Ralston Papers.]

Ralston formed a law partnership with John A. Abbott in Lebanon, Boone County, in June 1886.

[6] “Democrats to Have Own Way,” Indianapolis News, November 6, 1912, 1; “Indiana for Wilson by 100,000, with 60,000 for Ralston, Late Estimate,” Indianapolis Star, November 6, 1912, 1; “Sweeping Democratic Victory in Nation and the State,” Greenfield Republican, November 7, 1912, 1; “Ralston Elected Indiana’s Governor,” Lebanon Pioneer, November 7, 1912, 1, submitted by applicant; “Ralston Takes Oath of Office at Noon Today,” Indianapolis Star, January 13, 1913, 1; “Ralston Takes Up The Reins,” Indianapolis News, January 13, 1913, 1; “J. P. Goodrich Now Governor,” Indianapolis News, January 8, 1917, 1; “Goodrich Ready to Take Seat,” Indianapolis Star, January 8, 1917, 1. [All newspapers this note accessed Newspapers.com unless noted.

In November 1912, Ralston was elected governor of Indiana. He served January 13, 1913 to January 8, 1917 as 29th Governor of Indiana.

[7] “An Act Concerning Utilities, Creating a Public Service Commission, Abolishing the Railroad Commission of Indiana, and Conferring the Powers of the Railroad Commission on the Public Service Commission,” Approved March 4, 1913, Amended March 8, 1915, , Laws of the State of Indiana, 69th Session of the General Assembly (Indianapolis: Wm. Buford Printer, 1915), 457; “Public Utilities Measure Signed,” Richmond Palladium and Sun-Telegram, March 5, 1913, 6, Newspapers.com; “Public Utility Act Is Now Complete Measure,” Indianapolis News, March 5, 1913, 3, Newspapers.com; “Gov. Ralston Signs Public Utilities Bill,” Muncie Star Press, March 5, 1913, 3, Newspapers.com

Governor Ralston advocated for the creation of a public utilities act, met extensively with lawmakers and utilities companies, and drafted the final version of the bill. The act placed natural gas, water, sewer, electric, telephone, and other services under the regulation of the agency formerly known as the Railroad Commission, which was renamed the Public Service Commission. The measure, known as the Shively-Spencer public utilities act, redefined utilities as being both publicly and privately owned and thus rightly regulated by citizens through their government. The Muncie Star Press reported:

The law is based on the principle that public service corporations are neither public nor private, but quasi-public; that these corporations have received rights and privileges from the public and owe certain duties to the public. Regulation is taken to be the right and duty of the people acting through government agencies.

Ralston signed the act March 4, 1913. It took effect May 1. Ralston was highly praised by Indiana newspapers for his role in the passage of the act, though he was criticized for appointing only lawyers to the commission. Hoy summarized the impact of the public utilities law thusly: “It created the basis for a fair exchange between the people who invest money in a service designed of the public’s welfare or convenience and the people who pay for that service.” The agency still exists today. It was renamed the Indiana Utility Regulatory Commission in 1987. According to the commission’s mission statement, the commission “hears evidence in cases filed before it and makes decisions based on the evidence presented in those cases. An advocate of neither the public nor the utilities, the Commission is required by state statute to make decisions in the public interest to ensure the utilities provide safe and reliable service at just and reasonable rates.”

For information on the Public Service Commission’s role in arbitrating the Indianapolis streetcar strike of 1913, see footnote 9.

[8] “Governor Issues Appeal for Aid,” Indianapolis Star, March 27, 1913, 12; “Asks Government to Send Medical Expert,” Indianapolis News, March 27, 1913, 14; “Bayonets Bar Way to Flood District,” Fort Wayne Sentinel, March 28, 1913, 5; “More Calls Reach Indiana Governor,” (Richmond) Palladium-Item, March 31, 1913, 2; W. K. Katt to the Indiana Engineering Society, “Flood Protection in Indiana,” speech printed in American Contractor, January 30, 1915, 72, accessed GoogleBooks; Phillips, 215-216; : Indiana Department of Natural Resources, “Indiana Underwater: The Flood of 1913,” https://www.in.gov/dnr/historic/files/hp-1913_flood.pdf. [Newspapers this note accessed Newspapers.com.]

Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and New York received several months’ worth of rainfall in only two days on March 24 and 25, 1913, according to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources. Severe flooding impacted Indiana residents along the Wabash, White, and Ohio Rivers and their tributaries.

Clinton Norquest, Indianapolis Weather Bureau Observer at the time, reported to the National Weather Service:

Water states reached were from 2 to 8 feet higher than those recorded in any previous flood; the loss of life and property was unprecedented; thousands were driven from their homes, fleeing for their lives; transportation lines were helpless through loss of track and bridges; telephone and telegraph lines were crippled; communities were cut off from communication with the outside world for from 24 to 48 hours; cities were deprived of light and power by the flooding of power plants; isolated towns were threatened with famine; and for a period of 3 days or more the great commercial enterprises of the State were at a standstill.

On March 26, Ralston accompanied the quartermaster of the Indiana National Guard “to get first-hand information” about the flood damages, according to the Indianapolis Star. The newspaper reported, “The Governor was much impressed with the need of extending immediate assistance.” Ralston had only $15,000 in an emergency fund and thus that evening “issued a call to the people of Indiana to assist in giving relief to flood victims.”

That same day, the governor worked to distribute food, clothing, medical supplies donated by Montgomery Ward & Co., the Pennsylvania Railroad, and the Pittman-Meyers Company. He sent immediate relief to the hard hit citizens of Logansport, Terre Haute, and Peru. The Star reported that Ralston barely slept for several days as he orchestrated the flood relief. He contacted the National Relief Board of the American Red Cross accepting their offer of financial assistance.

According to Geoff Williams’ 2013 monograph Washed Away, President Woodrow Wilson sent telegrams on March 26 to the governors of Ohio and Indiana offering federal aid. Ohio’s governor responded and the president instructed the Secretary of War to send tents, rations, supplies and medical personnel. Williams claims that Ralston never received the telegram as the flooding prevented its delivery to him from the telegraph office. However, the Indianapolis Star that Ralston had received “an offer of assistance from Secretary of War L. W. Garrison who authorized the state to use any government supplies available for the sheltering of the homeless.” The paper also printed the text of the telegram in which Garrison offers officers, troops, and supplies.

On March 27, Ralston dispatched National Guard companies to Logansport and Indianapolis to help with relief and to prevent looting. Ralston was also ready to declare martial law to prevent anyone from profiting by raising food prices during the crises. The Indianapolis News reported that Ralston stated: “It is not right for men to try to make money out of misfortune. I will raise the devil with any one that tries it.” By March 28, the governor received telegrams from around the country with offers of aid and calls for help. This went on for days. On March 31, the (Richmond) Palladium-Item reported “The receding of the flood waters . . . has not relieved the strain under which Governor Ralston and other state officials have been working since the high waters first made their appearance.” Ralston continued to coordinate relief efforts over the following days, making calls to officials around the state.

To learn about the flood’s impact on the different regions of the state see: Indiana Department of Natural Resources, “Indiana Underwater: The Flood of 1913,” https://www.in.gov/dnr/historic/files/hp-1913_flood.pdf

According to W. K. Hatt, Purdue University professor of civil engineering at the convention of the Indiana Engineering Society, the final toll of the flood was thirty nine lost lives and eighteen million dollars’ worth of destroyed property. In response, Ralston appointed the Indiana Flood Commission April 20, 1914 “to consider the extent of damage due to floods in the state of Indiana, and to report to the governor what measures should be taken to provide relief in the future.” According to historian Clifton Phillips, however, the commission’s studies produced no decisive action.

[9] “New Effort to End Car Strike Fails to Carry,” Indianapolis Star, November 6, 1913, 1, ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “Uphold Law Is Ralston’s Plea,” Indianapolis Star, November 7, 1913, 14, , ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “Strike of Street Car Men Settled,” Indianapolis News, November 8, 1913, 5, Newspapers.com; “Full Text of Agreement,” Indianapolis News, November 8, 1913, 5, Newspapers.com; “Speech of the Governor,” Indianapolis News, November 8, 1913, 5, Newspapers.com; “I. & C. Company and Men Agree to Arbitration,” Indianapolis Star, November 12, 1913, 1; ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “Lauds Ralston for Action in Local Car Controversy,” Indianapolis Star, November 22, 1913, 16, ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “Ralston Lauded for Peace Move,” Indianapolis Star, November 16, 1913, 12, ProQuest Historical Newspapers; “Indianapolis Lockout Settlement,” Motorman and Conductor (November 1913) 21:12. 29-34, GoogleBooks; Hoy, 97-124. The following explanation of the strike is summarized from Hoy’s dissertation and fact-checked using Indianapolis newspapers.

By the fall of 1913, the recently-unionized Indianapolis streetcar workers employed by the Traction and Terminal Company were striking for better wages and working conditions along with shorter regular hours and overtime pay. The company and its president Robert I. Todd refused to meet with workers or their union representatives and used hired “sluggers” to use fear to dissuade workers from organizing and striking. On October 31, 1913, union leaders called for a massive strike during the week of statewide municipal elections. On November 1, the workers completely halted the streetcars. By the following day, “the strike had erupted into open warfare,” according to Hoy. Todd had called in strikebreakers, who clashed with the striking workers resulting in many injuries and two deaths. Local politics and disagreements between the sheriff and mayor resulted in an inadequate response by law enforcement. The company failed to respond to calls for arbitration by local labor and religious leaders. Ralston tried to give law enforcement time to handle the situation as required by statute, but was soon forced to act. He quietly called in the National Guard on November 5 and placed them on standby.

On November 6, Ralston addressed protesters from the statehouse steps, promising that he would work for arbitration. The workers responded by agreeing to negotiate only for better pay and conditions and not recognition by the company of their union. Ralston then negotiated with Todd and the president of the Central Labor Union and met with the Public Service Commission. Ralston added pressure to make an agreement by threatening to declare martial law. Finally, he was able to negotiate a temporary settlement. The workers would return to their jobs, working no more than twelve hour shifts, while the company had ten days to satisfy the rest of their complaints before the matter would go to the Public Service Commission. The strike and the violence ended. The matter was decided by the Public Service Commission between December 1913 and January 1914. Ralston spoke to the commission on behalf of the workers. In the end, the workers got a very small raise, better hours, but no overtime pay. The company did, however, agree to install a permanent arbitration board and the commission demanded that there could be no retribution for unionizing. Read the full agreement. Ralston was praised by newspapers of both Democratic and Republican leanings and was satisfied by the role of the Public Service Commission as arbiter and a lasting legacy of his administration.

[10] “Gov. Ralston’s Message Read to the General Assembly,” Jasper Weekly Courier, January 8, 1915, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “An Act Creating a State Historical Commission, Providing for the Editing and Publication of Historical Materials and for an Historical and Educational Celebration of the Indiana Centennial,” Approved March 8, 1915, Laws of the State of Indiana, 69th Session of the General Assembly (Indianapolis: Wm. Buford Printer, 1915), 455; James A. Woodburn, “The Indiana Historical Commission and Plans for the Centennial,” Indiana Magazine of History 11:4 (December 1915), 338-347; Suellen M. Hoy, “Governor Samuel Ralston and Indiana’s Centennial Celebration,” Indiana Magazine of History 71:3 (September 1975), 246-8, accessed IMH Online, Indiana University.

Indiana became a state in 1816, and thus by 1915, was busy preparing to celebrate its centennial of statehood the following year. When Governor Ralston addressed the General Assembly on January 7, he tasked the legislators with creating a centennial commission and appropriating $25,000 for a dignified statewide public celebration. The measure passed unanimously and Ralston approved the act creating the Indiana Historical Commission on March 8, 1915. The act appointed three ex officio members of the commission: Indiana University Professor James A. Woodburn, Earlham College Professor Harlow Lindley, and Governor Ralston. The governor was tasked with appointing six other members to create a nine-member commission. Short biographies of the members are available through the Indiana Historical Bureau.

The act instructed the Indiana Historical Commission to “collect, edit and publish documentary and other materials on the history of Indiana” and “prepare and execute plans for the centennial celebration in 1916, of Indiana’s admission to statehood.” For examples of some of the celebratory activities see: Woodburn’s article cited above.

The legacy of the Indiana Historical Commission continues as the organization evolved into the Indiana Historical Bureau, the state agency tasked with installing state historical markers and providing “publications, programs, and other opportunities for Indiana citizens of all ages to learn and teach about the history of their communities, the state of Indiana, and their relationships to the nation and the world.”

[11] “Richard Lieber Heads State Park Committee,” Indianapolis News, March 18, 1916, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; "A System of State Parks," Indianapolis News, March 23, 1916, 6, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Power of Press Invoked to Aid State Park Fund, Greencastlr Herald-Democrat, March 24, 1916, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Park Contribution Week Designated by Governor,” Indianapolis News, April 13, 1916, 8, Hoosier State Chronicles; Walter S. Greenough, “Governor Favors Park Commission,” Indianapolis News, July 4, 1916, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Turkey Run Is Now State Park,” Indianapolis News, November 11, 1916, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; Richard Lieber, “Report of State Park Committee,” Year Book of the State of Indiana for the Year 1917 (Indianapolis: Wm. B. Burford, 1918), accessed through Indiana University Digital Library; Lindley, Harlow, ed. Indiana Centennial, 1916: A Record of the Celebration of the One Hundredth Anniversary of Indiana's Admission to Statehood (Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Commission, 1919); Phillips, 221-223.

Governor Ralston advocated for the establishment of Indiana State Parks as the lasting legacy of the Indiana Historical Commission’s centennial celebration. He also helped with negotiations to acquire land and fundraising. On March 18, 1916, the Indianapolis News reported: “The state park memorial committee of the Indiana historical commission which is organizing for the specific purpose of establishing the foundation of a system of state parks as the permanent feature of the Hoosier centennial celebration, formally began its movement today.” The committee would also absorb the Turkey Run Commission which Ralston had established at the urging of writer Juliet Strauss. In March, Ralston sent a letter to the newspapers of the state urging them to work with other organizations to raise funds and authorizing them to receive subscriptions for the park fund. In April, Governor Ralston proclaimed “Park Contribution Week.” The proclamation reviewed the progress the Historical Commission had made in its plan to create state parks and announced that the State Park Memorial Committee (created by the commission) would raise funds “by means of public subscription . . . to acquire scenic tracts and historic spots in various parts of Indiana and thus lay the foundation for a state-wide parks system…” He concluded the proclamation: “Therefore, I, Samuel Ralston, Governor of Indiana, believing in the great civic value that in the present and succeeding generations will come to the people of Indiana through the proposed system of state parks, do urge upon our people to give of their means to this public park fund . . . Through their giving the people will not only show their civic patriotism in most substantial and lasting form in this centennial year, but will secure the creation of this splendid state park heirloom which may be handed down to oncoming generations . . .”

On July 4, Indianapolis News correspondent Walter S. Greenough reported from Turkey Run that Governor Ralston “announced in an address before many hundred in the park here this afternoon that he will ask the next general assembly in Indiana to pass a law creating a state park commission . . . He would empower that commission as well as the several boards of park commissioners in Indiana, to condemn the lands in Indiana’s natural ‘beauty spots’ for park purposes.” In 1916, McCormick’s Creek became the first Indiana state park, followed in 1917 by Turkey Run. The Indianapolis News reported November 11 that Ralston played an important part in negotiations with the property owner and other efforts to save Turkey Run as a state park. For a complete history of the early history of the Indiana State Parks see the “Report of the State Park Committee” in the 1917 Indiana Year Book.

[12] “Ralston Wins Senate Race; Lead Growing,” Richmond Palladium, November 8, 1922, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles; “Beveridge Sends Congratulations to S. M. Ralston: Concedes the Election of Democrat As Senator,” Lebanon Daily Reporter, November 8, 1922, 1, submitted by applicant; “Ralston to Leave for Senate Nov. 28,” Greencastle Herald, November 17, 1923, 1, Hoosier State Chronicles;

“Ralston, Samuel Moffett,” Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, http://bioguide.congress.gov/scripts/biodisplay.pl?index=R000020

Ralston served as a United States senator form March 4, 1923 until his death October 14, 1925.

[13] “Dr. McCulloch Is Made Nominee on the Third Ballot,” Garrett Clipper, June 9, 1924, 6, Newspapers.com; “Ralston Repeats Klan Denial in Emphatic Manner,” Indianapolis Star, June 29, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com; “Newspaper Quotes Indiana Lawyer in Ralston-Klan Tale,” Indianapolis Star, July 3, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com; “Ralston Gives Reasons Anent Quitting Race, (Muncie) Star Press, July 5, 1924, 1, Newspapers.com.

On June 6, 1924, the Indiana delegation to the democratic national convention in New York pledged support for Senator Ralston for the presidential nomination. Ralston objected to the nomination, but said he would do his best to represent the democratic platform if elected. There were several candidates, none a major front runner and the convention lasted many weeks and took an unusually large number of votes. When it seemed the nomination would go his way, the New York Work, which supported another candidate, ran several stories suggesting he had the support of the Klan. While Ralston repeatedly denied ever being a member of the Klan, he did not clearly denounce the organization itself. (For more information see: “Complicity in Neutrality: Samuel Ralston Denies Klan Affiliation, Indiana History Blog, https://blog.history.in.gov/?p=4538&preview=true.) On July 4, Ralston official withdrew his name from consideration for presidential nominee.

[14] Death Certificate, Samuel Moffett Ralston, October 14, 1925, Certificate 32663, Indiana State Board of Health, Indiana Death Certificates, 1899-2011, Indiana State Archives and Records Administration, accessed Ancestry Library; “Ralston Funeral Saturday at Lebanon, Old Home: Indiana, Nation Mourn Death of Statesman,” Indianapolis News, October 15, 1925, 1, Newspapers.com; “U. S. Senator Ralston Dead,” Indianapolis Star, October 15, 1925, 1, Newspapers.com; “Samuel Moffett Ralston,” photograph of grave, findagrave.com.

Ralston died October 14, 1925 “at his country place, Hoosier Home, northwest of Indianapolis,” according to the Indianapolis News. His funeral took place at the Lebanon Presbyterian Church. He is buried at Oak Hill Cemetery in Lebanon, Boone County, Indiana.