Bishop William Paul Quinn

Location: 200 6th St., Richmond (Wayne County, Indiana) 47374

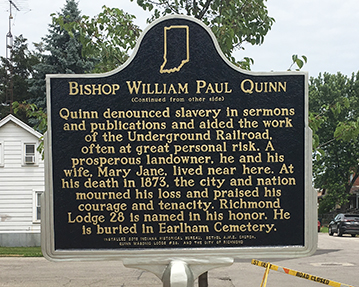

Installed 2018 Indiana Historical Bureau, Bethel A.M.E. Church, Quinn Masonic Lodge #28, and the City of Richmond

ID#: 89.2018.2

Text

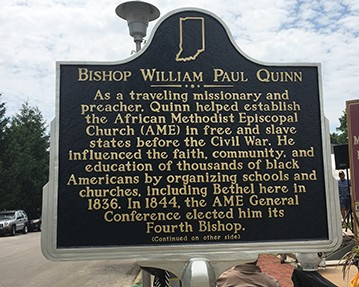

Side One:

As a traveling missionary and preacher, Quinn helped establish the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in free and slave states before the Civil War. He influenced the faith, community, and education of thousands of black Americans by organizing schools and churches, including Bethel here in 1836. In 1844, the AME General Conference elected him its Fourth Bishop.

Side Two:

Quinn denounced slavery in sermons and publications and aided the work of the Underground Railroad, often at great personal risk. A prosperous landowner, he and his wife, Mary Jane, lived near here. At his death in 1873, the city and nation mourned his loss and praised his courage and tenacity. Richmond Lodge 28 is named in his honor. He is buried in Earlham Cemetery.

Annotated Text

Side One:

As a traveling missionary and preacher, Quinn helped establish the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME) in free and slave states before the Civil War.[1] He influenced the faith, community, and education of thousands of black Americans by organizing schools and churches, including Bethel here in 1836.[2] In 1844, the AME General Conference elected him its Fourth Bishop.[3]

Side Two:

Quinn denounced slavery in sermons and publications and aided the work of the Underground Railroad, often at great personal risk.[4] A prosperous landowner, he and his wife, Mary Jane, lived near here.[5] At his death in 1873, the city and nation mourned his loss and praised his courage and tenacity.[6] Richmond Lodge 28 is named in his honor.[7] He is buried in Earlham Cemetery.[8]

[1] “Notice,” Freedom’s Journal (New York), May 4, 1827 accessed Accessible Archives, photocopy from applicant; “To the Public,” The Liberator, January 5, 1833 accessed Accessible Archives; “(From the Pittsburgh Conference Journal.),” The Liberator, December 20, 1834 accessed Accessible Archives; Daniel A. Payne, History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church (Nashville, TN: 1891), v, 7, 14, 27, 34, 96-98, 112,126, 131, 137, 221 accessed Documenting the American South; “The Origins of the African Methodist Episcopal Church,” accessed NationalHumanitiesCenter.org; Carol V. R. George, Segregated Sabbaths, Richard Allen and the Emergence of Independent Black Churches 1760-1840 (New York, NY: 1973), 6, 8, 175; Albert J. Raboteau, A Fire in the Bones (Boston, MA: 1995), 79 accessed Google.com; Gayraud S. Wilmore, Black Religion and Black Radicalism (Maryknoll, NY: 1998), 103.

In the eighteenth century, most church-going African Americans attended white churches. Even free blacks in the North were denied full participation in the activities of the church. In Philadelphia, in the 1790s, free blacks led by Richard Allen and Absolom Jones walked out of St. George’s Methodist Church. They worked to establish an independent, black church. In Philadelphia, in 1816, Richard Allen led the organization of several independent black Methodist churches from the region into the first organized black denomination in the U.S. This organization, the African Methodist Episcopal Church (AME), was described by historian Albert Raboteau as: “the most important black denomination and arguably the most important African-American institution for most of the nineteenth century.” It served “as a center for social organization, economic cooperation, educational endeavor, leadership training, political articulation, and religious life.” According to historian Gayraud S. Wilmore, the independent black church movement “must be regarded as the prime expression of resistance to slavery—in every sense, the first black freedom movement.” Historian Carol George explains that this new AME denomination “limited membership to Africans and vigorously attacked slavery and the slave trade.”

Rev. Daniel A. Payne, an AME historian, gathered the printed Minutes of the early AME Conference meetings to inform his History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church published 1891. William Paul Quinn told Payne (who later became an AME bishop) that he attended the 1816 Philadelphia meeting as an eighteen or nineteen year old. From Payne’s History, we learn that Quinn had become an AME member by 1818 and had represented Baltimore at their AME Annual Conference meetings of 1818 and 1819. Later, Quinn’s AME ministry and travels took him to Pittsburgh, New York, and Boston. Sometime in the late 1820s Quinn separated from the AME Church. He petitioned to be re-admitted in 1833 and was sent to the Ohio Conference. In 1834 the Church sent Quinn to the AME Station in Cincinnati.

By 1836, Quinn is simply listed in the General Conference minutes as a “traveling preacher.” In 1840, the General Conference appointed him to the “very important office of missionary to plant churches in the far West.” By 1841, Quinn served as Presiding Elder of five new AME Church circuits in Indiana, Illinois, and the slave state of Missouri.

a href="#_ednref2" name="_edn2">[2] 1865 Directory and Soldier’s Register of Wayne Co., Indiana (J. C. Power, 1865), 164-65, Indiana State Library, photocopy; Payne, 98, 111, 167-172; Daniel A. Payne to Dr. Garnett, The Christian Recorder, April 10, 1873, accessed Accessible Archives; Gilbert H. Barnes and Dwight L. Dumond, eds., Letters of Theodore Dwight Weld, Angelina Grimke Welde and Sarah Grimke 1822-1844 Vol. 1 (New York, NY: 1934), 178-179; William Cheek and Aimee Lee Cheek, John Mercer Langston and the Fight for Black Freedom, 1829-65 (Chicago, IL: 1996), 53-54; Gayraud S. Wilmore, Black Religion and Black Radicalism (Maryknoll, NY: 1998), 103; Alice Ferguson, Bethel African Methodist Episcopal Church (Richmond, IN: 2005), [1].

The Ohio AME Annual Conference meeting was held in Pittsburgh in 1833. Quinn was present when, according to Payne, p. 98, the first resolutions of the AME church regarding education were passed. The members of that Conference resolved “that common schools, Sunday-schools, and temperance societies are of the highest importance to all people; but more especially to us as a people.” Every member of the Ohio Conference was charged “to do all in his power to promote and establish these useful institutions among our people.”

Quinn took this charge seriously when he was stationed in Cincinnati in late 1834. Historians William and Aimee Lee Cheek describe AME minister, William Paul Quinn, as one of the black leaders in that city working with the followers of white abolitionists Theodore Weld and Augustus Wattles to establish “an extensive program of instruction and uplift” there. A letter from Cincinnati, December 15, 1834, to Theodore Weld corroborates Quinn’s activities: “Brother Quit [sic], the new Minister of our colored church, takes hold with us and is I should think doing well. He attends all our Lectures and does what he can both publicly and privately to increase the attendance.”

As a “traveling preacher,” William Paul Quinn came to Indiana in 1836. The 1865 Directory and Soldier’s Register of Wayne County reports that he organized the AME congregation in Richmond, Indiana, on September 23, 1836. Daniel Payne’s History, p. 111, reports than an AME circuit was established in 1836 with Richmond as its base. For eight years Quinn traveled Indiana, Illinois, and Missouri planting churches and schools. Elder Quinn gave “a brief outline of the rise and progress of our mission in the West” to the 1844 AME General Conference meeting. He counted roughly 18,000 “colored inhabitants” in Indiana and Illinois. Among the black communities in these states, Quinn led the establishment of forty-seven churches, seventy-two congregations, forty schools, fifty Sabbath schools, and forty temperance societies.

Quinn also extended his AME mission into Missouri and Kentucky. His 1844 report continued: “Though slave states, yet a more friendly feeling exists towards our enterprise among the ruling authority than could be easily anticipated…. I am fully persuaded this mission, if faithfully conducted, will, at no distant period, accomplish wonders for our people settled in these western states in their moral and religious elevation.”

AME Bishop Daniel A. Payne wrote a letter to abolitionist Henry Highland Garnet, published in the April 10, 1873 Christian Recorder. Payne described Quinn’s work and influence: “commencing his itinerant labors as early as 1818, he lived to see marvelous changes in the condition of the Denomination and the race for whose well-being he planned and executed. In his presence the handful of preachers had become a thousand, the two thousand members nearly a quarter of a million….”

[3] “The South Again in Peril,” The National Era (Washington, D.C.), November 9, 1854, 178, accessed ChroniclingAmerica; Benjamin T. Tanner, An Apology for African Methodism (Baltimore, MD: 1867), 144-147, accessed Documenting the American South; Payne, 171-172, 222.

The 1842 Ohio Annual Conference recognized the scope of Quinn’s work:

The Western Christian Mission, as devised by the General Conference, held in the city of Baltimore, in 1840, and prosecuted by Rev. Wm. Paul Quinn, in the States of Indiana, Illinois and Missouri, is the greatest Christian enterprise ever undertaken by the African M. E. Church since its rise and progress in our country. Its present wide spreading influence and future prospect of good to the present and rising generations in the Western States, entitle the Agent, Brother Quinn, who, with untiring zeal, prosecuted the mission to that honor and esteem by this Conference, which is due, and is paid to all men of great minds and enterprizing [sic] habits.

Daniel Payne reported, from the Minutes of the 1844 General Conference, that Quinn’s work in the west “produced important effects upon the minds of the brethren.” Payne adds “when they saw how useful and important Brother Quinn had been, they said within themselves, ‘Surely this is the man for the Bishopric.’” Quinn was elected to that office by the members of that Conference; he was consecrated Bishop on May 19, 1844.

Under Bishop Quinn’s leadership, the AME church expanded into the deep South. In 1848, the Indiana AME Conference received a petition from New Orleans, Louisiana asking to establish an independent AME church in that city. Their petition was approved. In 1854, The National Era published a story, “The South Again in Peril,” compiled from several newspaper accounts. In summary, the article states that sometime in 1852, Bishop Quinn himself traveled to New Orleans to ordain deacons and elders. While there, Quinn wrote a letter that was published in a newspaper called the Recorder, (location unknown). In the letter, Quinn “speaks encouragingly of the cause in the South.”

The column continues: by 1854, however, “the fears of our Southern friends are just now excited by the fact that the African Methodist Episcopal Conference has a church or two under its care in New Orleans, and that there is come talk of establishing one in Mobile.” The Methodist Episcopal Church South felt “periled by having this questionable organization.” An independent black church of free blacks “may nurture feelings of self-respect and habits of self-reliance in that class of our population, and the example may be mischievous by quickening in the slaves the latent idea of manhood. Therefore, it is questionable, in fact, dangerous, and must be put down.”

[4] “Murderous Assault—Robbery.” Broad Axe of Freedom & the Grubbing Hoe of Truth, February 20, 1858, 3, photocopy from applicant; Benjamin T. Tanner, An Outline of our History and Government for African Methodist Churchmen (Philadelphia, PA: 1884),173, accessed Documenting the American South; In Memoriam, Funeral Services in Respect to the Memory of Rev. William Paul Quinn (Toledo OH: 1873), 14, 16, 22, 26, accessed Google Books; Laura S. Haviland, A Woman’s Life-Work: Labors and Experiences of Laura S. Haviland (Cincinnati, OH: 1882), 178; Payne, 84; Carol V. R. George, Segregated Sabbaths, Richard Allen and the Emergence of Independent Black Churches 1760-1840 (New York, NY: 1973), 4, 8, 175, 184; “The Origin, Horrors, and Results of Slavery, Faithfully and Minutely Described, in a Series of Facts, and its Advocates Pathetically Addressed. By the Rev. W. Paul Quinn, of African Descent.” (Pittsburgh, 1834), 614-35 in Dorothy Porter, ed., Early Negro Writing, 1760-1837 (Baltimore, MD: Black Classic Press, 1995), 614, 618, 620; Cheryl J. LaRoche, Black Communities and the Underground Railroad (Urbana, IL; University of Illinois Press, 2013), Preface, Introduction, accessed Google Books: Eric Foner, Gateway to Freedom, The Hidden History of the Underground Railroad (New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company, 2015), 6.

In 1873, Reverend Benjamin Arnett at the Toledo, Ohio funeral service for Bishop William Paul Quinn, explained the aims of the AME church: “The general purpose was to assist in bringing the world to the foot of the Cross of Christ; and the special purpose was to assist in relieving the African race from physical, mental and moral bondage.” Founding AME Bishop Richard Allen set an early example of the church’s “special purpose.” Daniel Payne writes that Allen was “thoroughly ‘anti-slavery,’ his house was never shut ‘against the friendless, homeless, penniless fugitives from the House of Bondage’.” According to historian Carol George, the ministers who followed after Allen in the AME church “adopted his ideas and approach to meet the demands of their own time.”

Daniel Payne’s History follows William Paul Quinn’s work to extend and promote the “purposes” of the AME church in the black communities in the West. As Quinn pursued this mission, his “reputation as a preacher soon increased so much that when he arrived in a neighborhood every body, white and colored, went to hear him. . . . He shut the mouths of that class of men who often declared that a colored man could not do anything.” (Funeral Services) Quinn’s thoughts about slavery and abolition are preserved in a pamphlet, “The Origins, Horrors, and Results of Slavery. . . .” published 1834. He bluntly states that “Slavery is only another word for brutal cruelty.” Quinn exhorts all: “Shall we not, as patriots, as philanthropists, as freemen, and as Christians, stir ourselves and be resolved to seek the entire extirpation of a system that is equally alike destitute of all justice as of mercy. . .?”

A few scattered sources provide clues about his abolitionist activities and the perils he faced. He wrote from Indianapolis, 1844: “To accomplish this great enterprise, I have been compelled to lie out in the wilderness more than two hundred nights, and have been brought before the grand jury in St. Louis, three different times, and honorably acquitted—thanks be to God.” (Tanner, 173) In her memoir, Michigan abolitionist, Laura Haviland reports that Bishop Quinn gave $5 to her at Newport, Indiana as she traveled to Toledo with “several fugitives.” A Richmond, Indiana newspaper, The Broad Axe of Freedom, reported in 1858 that Quinn had been severely beaten and robbed in Cincinnati.

During the Civil War, “he [Quinn] went to the West, into Kansas, and gathered the Freedmen as they came across the lines into the army of the Union. Several times the rebels captured him. One time he escaped and swam the river while there was ice in it. But nothing daunted him.” (Funeral Services)

In Gateway to Freedom, historian Eric Foner asks readers to think about the underground railroad as an “an interlocking series of local networks.” Foner insists that “The growth of free black communities, North and South, in the first half of the nineteenth century proved crucial for the prospects of fugitive slaves.” In Black Communities and the Underground Railroad, Dr. Cheryl LaRoche agrees that “small communities of Black families in rural and border regions acted as conduits for escape before the Civil War.” LaRoche’s research finds that residents in these communities worked together through independent institutions and organizations like the AME church and the black Masonic fraternity to aid enslaved people and their families. The residents’ underground railroad activities “simultaneously ensured their own freedom and the liberty of family and friends.” The independent AME church and its ministers such as William Paul Quinn became “major forces for social change”.

Bishop Quinn’s mission to carry the AME church’s message of education and liberation to free blacks took him to the very communities best situated, according to historians Foner and LaRoche, to provide aid to enslaved blacks hoping for freedom. While we have more to learn about Quinn’s activities in and around those communities, Reverend Benjamin Arnett, who knew Quinn, called him “the main stay in the great conflict which culminated in the emancipation and enfranchisement of the race.” (Funeral Services)

[5] Indenture, Wayne County Indiana, Deed Record 11, October 4, 1848, p. 56-57; Indenture, Wayne County Indiana, Deed Record 11, November 15, 1848, p. 87; Indenture, Wayne County Indiana, Deed Record 12, October 24, 1849, p. 231; Affidavit, February 12, 1851, Pittsburgh PA, copy recorded in Wayne Co., Indiana Deed Record 14, p. 314-15, photocopy from applicant; Indenture, Wayne County Indiana, Deed Record 21, March 10, 1856, p. 265; Indenture, Wayne County Indiana, Deed Record 26, October 13, 1859, p. 304-05; Indenture, Wayne County, Indiana Deed Record 42, July 9, 1866, p. 359; “Bishop Quinn Married,” Indiana True Republican, July 12, 1866, 7, photocopy from applicant; Richmond (Weekly) Palladium, June 8, 1869, 3 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Paul Quinn, 1870 U. S. Census, Richmond Ward 4, Wayne County Indiana, Roll M593_371, page 559, Image 219 accessed Ancestry.com; Payne, 318-22.

There has been much speculation about Bishop Quinn’s life before 1816. Rev. Arnett (Funeral Service) quotes No. 45 of the Richmond (Indiana) Independent. The article relates that the Bishop’s age at his death was somewhere between 76 and 94. He was born in Calcutta, India into a wealthy family engaged in mahogany trade. In India, he became greatly influenced by Mary Walder, a Quaker minister, and when his father rejected him, Quinn moved to England. There he became friends with Elias Hicks who brought him to New York. Quinn eventually moved to Maryland and there converted to the Methodist church.

However, a copy of a deposition at the Wayne County Recorder’s Office (originally recorded in 1851 in Pittsburgh, Pa.), states that Quinn was born in Honduras, Central America and that he has lived in the U.S. for more than 24 years—mostly in Pennsylvania and Indiana and he is a citizen of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Quinn is described as having dark brown eyes; he is six feet 1 3/4 inches tall with long, straight hair. Quinn’s mother was a native of Egypt and his father was a Spaniard in the mahogany business in Honduras. This deposition is a legal document signed with witnesses and verified by a notary public. Corroboration of this document is beyond the scope of this project.

Additionally, Bishop Payne reports of Quinn telling the members of the 1856 Canadian AME Conference in Chatham, Ontario that he (Quinn) was still a British citizen and that he owned land in Canada.

Though Bishop Quinn spent much of his life traveling through the U.S. and Canada on behalf of the AME church, he became a substantial landowner. In fact, the 1870 U.S. Census lists his real estate holdings valued at $20,000 and his personal property at $2,000.

In Wayne County alone, deed records show that at one time or another Quinn owned a farm near Newport, Indiana and a lot in Dublin, Indiana. In 1866, the year Quinn married Mary Jane Symmes of Hamilton County Ohio, he purchased Lot Sixteen in the Wiggins Addition located near the AME church in Richmond. The June 8, 1869 Richmond (Weekly) Palladium reported that Quinn had purchased the brick church on the corner of Market and Marion in Richmond for $4000 “to be used by the A.M.E. Congregation.”

[6] Richmond (Weekly) Palladium, February 22, 1873, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Richmond Times, March 1, 1873, 5; Richmond Telegram, March 7, 1873, 3; In Memoriam, Funeral Services in Respect to the Memory of Rev. William Paul Quinn (Toledo, OH: 1873), 14, 22, 26; Richmond Independent, March 8, 1873; “Communications,” The Christian Recorder, March 20, 1873 accessed Accessible Archives; Daniel A. Payne to Dr. Garnett, March 26, 1873 in Christian Recorder, April 10, 1873 accessed Accessible Archives; Richmond (Weekly) Palladium, December 6, 1873 accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; C. S. Smith, A History of the African Methodist Episcopal Church: Being a Volume Supplement to A History . . . by Daniel Payne (Philadelphia, PA; Book Concern of the AME Church, 1922), 101, accessed Documenting the American South.

C. S. Smith records that at the 1872 AME General Conference in Nashville, TN, members of the meeting voted to give Bishop Quinn supernumerary (retired) status. Bishop William Paul Quinn died Friday, February 21, 1873 at his home in Richmond, Indiana. His funeral service and burial took place in Richmond on March 4, 1873. According to the Richmond Telegram, March 7, 1873, “On account of the limited size of the colored church, Bishop Paul Quinn’s funeral was held at the Pearl Street M. E. Church, on Tuesday afternoon, which was filled to its utmost capacity by whites as well as blacks. . . . His remains were followed to their last resting place by one of the most imposing processions seen in this city for several years.”

From Washington D. C., AME Bishops Campbell, Wayman and Ward published resolutions for the Richmond newspapers and the March 20, 1873 Christian Recorder stating that with Quinn’s death “the church has sustained a loss which is felt in every section of the country, and is irreparable because of the ability of the deceased.”

Funeral services for Bishop Quinn were held also in Toledo, Ohio on March 9, 1873 and in St. Louis, Missouri in December 1873. From Toledo, Ohio, Reverend Benjamin Arnett recalled Quinn’s service and his zeal:

The work that Bishop Quinn has done, since he was Bishop, is more than I can tell, but suffice it to say, that he has travelled throughout the United States more than any other man, living and dead, of our race and church. He worked in the Northern and Western States with a zeal unequalled by any of the fathers of our branch of the Church of God. . . . Thus he went from place to place, urging our people to educate and secure homes for themselves. Though age and hard labor told on him, he was always on the go; he could not remain still; he wanted to be on the march, or in the fight, in the camp was not his place. (p. 22)

[7] “Meeting Directory,” Richmond (Weekly) Palladium, June 11, 1857, 1, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “Colored Freemasons,” Daily Wabash Express (Terre Haute), June 22, 1867, 4, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; “The Negro in Business,” Indianapolis Recorder, December 21, 1901, 3, accessed Hoosier State Chronicles; Richmond Morning News, Monday, May 17, 1909, 1; Quinn Masonic Lodge web site.

The black Masonic fraternity was established in Indianapolis, Indiana circa 1849 according to Grand Master James S. Hinton speaking at the organization’s 1867 annual meeting in Terre Haute. According to the Richmond, Indiana Quinn Lodge web site history, the Prince Hall Masonic institution was organized in Richmond circa 1856. The earliest mention located to date of the “Britton Lodge (colored)” comes from the Richmond Palladium, June 11, 1857.

The date when the Richmond lodge changed its name to honor Bishop William Paul Quinn is unknown. The Indianapolis Recorder lists “Quinn Lodge, No. 28, Richmond” on December 21, 1901.

A new Masonic lodge building for Richmond African Americans was dedicated May 16, 1909. The building, located on South Sixth Street, was erected by Quinn Lodge, No. 28, and Adah Chapter, No. 21, Order of Eastern Star.

[8] Daniel A. Payne to Dr. Garnett, March 26, 1873 in Christian Recorder, April 10, 1873 accessed Accessible Archives; Beverly Yount, comp., Tombstone Inscriptions in Wayne County, Indiana (Fort Wayne, IN: 1968), photocopy from applicant.

After Quinn’s funeral in Richmond, Bishop Payne wrote to Dr. Garnett that the Richmond white Quakers and Methodists vied “with each other, for the privilege of honoring his [Quinn’s] lifeless form, by having the most important part of the obsequies performed in one of their beautiful chapels. His ashes now sleep in the elegant cemetery of the Quakers.”

Compiler of Wayne County Indiana Tombstone Inscriptions, Beverly Yount lists “Paul Quinn, Bishop of the A.M.E. Church” with those interred in Earlham Cemetery.

Keywords

Religion; African American