[Guest Post] Camp Chesterfield Serving the Midwest as a Spiritual Retreat for 128 years

Just east of Indianapolis, past Pendleton and next to Anderson, is an amazing spiritual retreat that is firmly a part of Indiana’s rich and distinctive religious heritage.

Since 1886, the Spiritualist church camp of the Indiana Association of Spiritualists (IAOS) — affectionately called “Camp Chesterfield” by the locals — has been offering visitors spiritual reprieve and comfort for the past 128 years.

I grew up in central Indiana and ventured all over the state as a child and teenager, and I never once heard of Camp Chesterfield. It wasn’t until I had a chance meeting with a Spiritualist medium in my hometown of Shelbyville did I even realize that such a place exist … and so close to home.

After visiting Camp Chesterfield in the mid-’90s for the first time, my interest was piqued. Why hadn’t I ever heard of this place, or more importantly, why hadn’t I ever learned about this American-made religion that has deep historical roots in Indiana?

That chance encounter eventually led me to research further Spiritualism’s colorful history. I decided to write my doctoral dissertation on the history of Spiritualism, focusing my primary research on Spiritualist mediums, many of whom reside in historic cottages on the grounds of Camp Chesterfield.

The advent of Modern Spiritualism began in 1848 when two sisters, Maggie and Katie Fox, of upstate New York, made intelligible contact with a spirit that had been haunting their home. This occurrence started a movement that literally changed the way many people in the 19th century viewed life and death.

Through a sensitive called a “medium,” people were given an opportunity to communicate with those who passed onto the other side of the veil.

Within two decades of the start of Modern Spiritualism, it has been estimated by historians that there were literally millions of adherents to this belief system. This is all the more amazing considering how sparsely populated the United States was in the mid-to-late 1800s.

Some of the most well-known people of the time converted to Spiritualism after attending a séance or upon receiving a message from a loved one who had passed away. Séances were purportedly held in the Lincoln White House, as well as in parlors and living rooms all across America. The Fox Sisters became so well-known that their notoriety would be akin to that of current celebrities like Kim Kardashian and Taylor Swift … including the rumors and gossip about their personal lives.

Spiritualism was not without its critics and skeptics. Traditional churches were mortified at how quickly people were embracing the “newfangled” religion. They began to fight back by accusing adherents of consorting with the devil.

Ignorance breeds fear; people who didn’t believe in ghostly apparitions or who hadn’t experienced spirit-communication personally, often harshly denounced the religion without knowing the facts.

For the record, it is a God-based religion that accepts the truth from all religious traditions, including Christianity, and in no way is connected to black magic or satanic worship. Spiritualism in many ways is no different than any other religion, except its adherents believe in the continuity of life after death which is proven through spirit-communication.

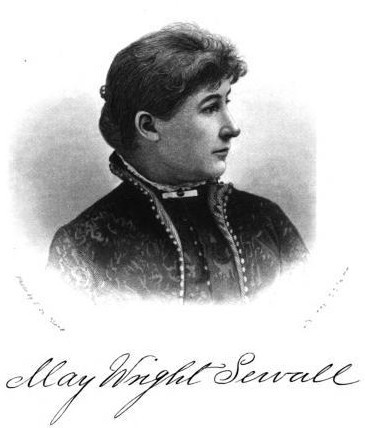

Noted Indianapolis suffragist and educator May Wright Sewall. Sewall was also a Spiritualist, and recorded her communications with her late husband and others in Neither Dead Nor Sleeping.

Old mediums, who are now “in Spirit,” maintained through oral history that Harry Houdini, the most outspoken critic of his day, often tried to sneak into séances and message services at Camp Chesterfield to try to debunk the mediums; he was never successful, even though he was quite persistent!

Houdini, an ardent critic of Spiritualism and an avowed skeptic of mediums, had an ongoing battle of words with perhaps the most famous Spiritualist of all time, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the creator of Sherlock Holmes. Doyle gave up writing stories about the famous detective to devote his life to writing about and documenting the history of Spiritualism.

Since multitudes of people began to flock to Spiritualist mediums, within a few years of the Fox sisters’ discovery, regular church meetings gradually organized around “camps” where visitors could attend services and have personal readings by the mediums.

This is how Camp Chesterfield came to be. After visiting a Spiritualist camp in Michigan, John and Mary Ellen Bussel-Westerfield of Muncie, decided that Indiana needed its own association and set out to find a suitable location for a homegrown Spiritualist camp.

Since 1886, the Indiana Association of Spiritualists has been meeting regularly; eventually the association settled permanently on the banks of the White River near Anderson in Chesterfield in 1890.

Initially, Camp Chesterfield was only a tent-based church similar to the old-style revival tents that itinerant ministers used to preach to the masses across the Midwest. The “high” season (from June to September) had the largest volume of visitors, who would camp out by the river, attend services and séances, and receive readings. Visitors were required to bring hay for their horses and their own utensils and food to cook their meals by campfire.

Today, Camp Chesterfield is a flourishing Spiritualist community equipped with a full-service cafeteria, a spacious cathedral, a modern bookstore and library, an art gallery and museum of Spiritualist artifacts, and a quaint little chapel in the woods. In addition, it boasts the first supposedly fire-proof hotel in the state of Indiana (many buildings in Indiana claim this distinction, however, so believe it or not!). The “Western Hotel” is a nostalgic building that allows visitors to step back in time upon entering its front doors. During the summer, visitors sit in the old-style gliders on the front porch chatting and exchanging messages they received from loved ones. Camp Chesterfield is historically significant for Indiana; it was listed in 2002 on the National Park Service’s “National Register of Historic Places.”

There is definitely something quite special and unique about Camp Chesterfield. Upon driving through its front gates, the meticulously kept grounds–which feature a variety of meditation sanctuaries and places to sit in self-reflection–offer visitors a peace and quiet that is rare in the modern world.

People who regularly visit Camp Chesterfield come from a variety of religious backgrounds. I have personally met a Methodist minister, Catholic nun, Tibetan monk, Episcopalian priest, Jewish mystic, American Indian shaman, and a myriad of other spiritual people who find solace and comfort from its healing grounds.

Whether strolling down the quaint little streets lined with trees past the mediums’ cottages, or through the center grounds, past the Garden of Prayer, Vesper Grove, Memory Garden or the Trail of Religions, the visitor to Camp Chesterfield is met with a sereneness that can be found only in spiritually charged places found in nature or churches; Camp Chesterfield is abundantly blessed with both.

Learn More:

For more information about special events, weekend and weekly seminars, message services, readings from mediums, or regularly scheduled classes at Camp Chesterfield, go to campchesterfield.net, or call the Camp Chesterfield Welcome Center at (765)378-0235.

Those with a casual interest in the history of Spiritualism might find American Spirit: A History of the Supernatural, a one-hour radio broadcast focusing on the topic, interesting.

Researchers interested in the history of this Indiana spiritualist community should visit Camp Chesterfield’s archive, the Hett Art Gallery and Museum, online or in person by appointment.

Thanks to Houdini’s thorough gathering of evidence in his crusade against spiritualism, many early books and pamphlets from the movement remain in the Houdini Collection at the Library of Congress. An extensive bibliography of digitized records, with links, from that collection is available from the University of Pennsylvania.